By J. G. FELTWELL

Courtesy of The Model Yachtsman

Years ago when there were no rating rules or restrictions, and handicaps were unknown, yacht racing resolved itself mainly into a matter of size, and the largest yachts generally won. Naturally this was very nice for owners of big vessels and very dull for owners of small craft.

In order to make competition closer and more interesting, handicaps were introduced. Some of these were based on performance and some on various systems of measurement. It is not my intention to trace the history of yacht racing, or discuss at length the various types of yacht produced under obsolete measurement formulæ. Early classification was, however, by various rules giving the measurement by tonnage, and the next advance was to form classes of yachts having the same tonnage, and thus class racing was evolved.

At one of the early international yachting conferences Professor Froude put forward the following definition:

“The legitimate purpose of a rating rule is simply to measure size; in order that the question of size being eliminated, the yachts that win shall be the fastest for their size; and that the model evolved under these conditions of competition shall be the speediest model.”

Professor Froude called this definition a “Primary or Ideal Principle,” and it is certainly a very excellent definition of a rating rule, which will be heartily endorsed by those who hold that it is no part of the proper function of a rating rule to mould the type of boat produced under it.

Experience has, however, shown that yachts evolved under a rule frequently owe their success to “measurement cheating” rather than genuine speed qualities. This might lead one to accept the sweeping conclusion that, as the character of the best measurement-cheating yacht is solely dependent on the measurement rule, the very idea of the speediest model is meaningless, except with reference to that particular rule. If we accept this view, a rating rule must be regarded solely as a means of carrying on yacht racing.

We might, however, be tempted to carry the matter a little further and ask whether in order to get fair competition under all conditions of weather it is necessary, to some extent, for a rating rule to define the type of boat produced? Moreover, it is incumbent to protect the interests of owners by framing the rule in such a manner that a desirable type of boat is evolved which is not liable to be rapidly outbuilt. This consideration is very necessary for the welfare of the sport as far as full-size yachts are concerned, and should also apply to models.

Professor Froude put forward a definition to cover this which he styled an “Alternative Principle” as follows:

“A rating rule is a serviceable contrivance by means of which class racing can be carried on; it should be convenient in working and should foster a desirable type of yacht.”

Now there are only three methods by which these objects can possibly be attained. The rating rule can consist of a set of restrictions, or of a measurement formula, or of a measurement formula used in conjunction with a set of restrictions. A careful analysis of these three methods and the resultant boats may help in the consideration of the possibility of an ideal rating rule. I will, therefore, deal with each of these three methods in turn, enumerating the conclusions I have drawn in each case.

Restricted Classes

The most restricted class of all is, of course, a One-Design Class. Here all the boats are built from the same design to the same specification, and are as far as possible exactly alike. They are frequently ordered in batches from the same builders at the same time, and a great saving of expense is thereby affected. They are usually designed especially to suit the water, and in many cases have provided excellent sport for a number of years. The type naturally varies with the locality. In Scotland deep draft and plenty of weight is favored. In the Thames Estuary centreboard craft of a powerful type are preferred owing to the necessity· of taking the mud between tides, whilst the Solent boats are powerful little craft suitable for the short seas they have to meet.

The best known One-Design Class in the world is the American “Star” Class. This is a sharpie type of boat and very popular in the United States, where it has attained the dignity of a yearly National Championship.

In Great Britain the most numerous One-Design Class is the Yare and Bure. These boats are a charming model from the design of Ernest Woods, of Cantley, Norfolk, and have a sailplan by the late Mr. Linton Hope. The ideal of a British National OneDesign Class has never been realized, however, owing to the different types needed to suit the varying conditions in different parts of the British Isles.

The main objection to a One-Design Class is that it only possesses a local interest, and this centres in the men who sail them rather than in the boats themselves. A further objection is that all competition in design is eliminated, and with it all opportunity of progress.

The term “Restricted Class” is usually taken to imply a class of boat for which the main dimensions are fixed. A celebrated designer once asked why we should trust to a complicated measurement formula, which might or might not give us the desired size and type, when we could fix the dimensions and be absolutely sure that our boat would not be outclassed by some extreme form of rule cheating.

In my opinion the rule cheater is often almost as possible under a restricted class as under a measurement formula, and should this happen, further restrictions would have to be imposed until finally all freedom of design would be eliminated.

In a Restricted Class with fixed dimensions practically every boat is designed right up to the limits, and consequently it is almost impossible to make those slight alterations in trim which so often make the difference between success and failure.

Some years ago Major B. Heckstall Smith, Secretary of the Yacht Racing Association, made the suggestion that for the purpose of rating model sailing yachts, all that is necessary is to fix the sail area and let the designer put whatever he likes in the way of a hull underneath it.

This is a very simple and interesting idea. The designer would have absolute freedom, and there is no doubt that in course of time the fastest type of hull would be developed, but it would, no doubt, be governed by local conditions.

Such a rule would not be practicable for real yachts. The expense would be too great owing to the boats being so rapidly outclassed by the development which would certainly take place under such a rule.

From an experimental point of view, some time or other, model yachtsmen might be tempted to give this idea the consideration it deserves. If such a class ever came into being, it would create considerable interest, but whether model yachtsmen would be pleased with the resultant craft is quite another matter.

No conclusions can be drawn from this suggestion, as the outcome would be too uncertain, but I suggest that, except in a very small class such as the 14-ft. dinghy, the attempt to class boats by means of restrictions alone must eventually result in limiting the designer’s freedom more than is desirable.

Measurement Formulæ

Restrictions are more or less direct in their effect, but a measurement formula is in reality an agglomeration of indirect restrictions. To take a very simple instance, let us consider the old Length. and Sail Area Rule. Here the designer is free to apportion his length and sail area as he likes so long as he does not exceed the class rating, but his sail area is strictly limited by his Load Waterline Length (LWL) or vice versa.

In consideration of measurement formulæ, it is also necessary to consider the underlying principles which governed their evolution. It must also be remembered that whilst a designer will modify certain features in order to take advantage of the rule he is working under, there are other very important features over which rating rules appear to have little or no influence.

Another point which must be borne in mind is that many of the conspicuous developments of type under various measurement formulae were due to novel expedients in building rather than to the influence of the rule.

Thus under the 1730 Rule (a tonnage rule) the tax on beam led to no remarkable developments until the introduction of the lead keel enabled sail to be carried effectively with a reduced beam. The ultimate outcome was naturally the “plank-on-edge” type which eventually caused the rule to be abandoned.

Again the extremely light displacement racing machine of the length and sail area Rule came in with the introduction of the bulb fin.

It might even be suggested that had the bulb fin been discovered earlier, the earlier rating rules might have produced very different boats from those which were successful in their own day. If so, it might seem that we might not be altogether justified in discarding Professor Froude’s Primary Principle as cited in the earlier part of this article, namely that the function of a rating rule is to measure size in order that the speediest model may be evolved.

This principle was departed from in the 1901 (the 2nd Linear Rule) and the succeeding rule. In these we had the girth difference measurement which was intended to produce a type. What the rule actually did was to put a premium on a particular shape, and I think that everyone will agree it was a bad shape at that.

The effect of the 3d measurement in the 1908 Rule was not so serious in the larger classes, but in the small classes the outcome was a narrow, over-canvassed, heavy displacement craft. It is probable that had the rule been retained, these features would have got more pronounced until we approximated the “plank-on-edge” type once more. This would have taken us back 40 years.

Measurement Formulæ with Restrictions

Our present I.Y.R.U. Rule was introduced in 1919, and has proved reasonably satisfactory, and provided very close racing in the 6, 8 and 12-metres classes. Under the rule the displacement is practically a fixed quantity and is in direct relation to the LWL. The designer is thus prevented from taking a little less displacement and sacrificing a little sail in order to get finer lines.

This rule, like its two immediate predecessors, is a Linear Rule. The term Linear Rule is used to distinguish a rule in which the factors entering into it are added or subtracted, as against a square or cubic rule when they are multiplied together.

It is held by many that a linear rule is superior to a cubic rule for the following reason:

Let us suppose that:

L + B + D = Rating

Taking values: 10 + 5 + 2 = 17

If we increase each of these dimensions in turn by 1, we get:

11 + 5 + 2 = 18 (or 6% increase)

10 + 6 + 2 = 18 (or 6% increase)

10 + 5 + 3 = 18 (or 6% increase)

Thus we see that an alteration of the same amount in any of the dimensions gives the same relative increase in rating.

In the cubic formula:

L × B × D = Rating

Giving the same values: 10 × 5 × 2 = 100

Increasing the dimensions as before:

11 × 5 × 2 = 110 (or 10% increase)

10 × 6 × 2 = 120 (or 20% increase)

10 × 5 × 3 = 150 (or 50% increase)

It will be seen that the smallest factor, which in a yacht is the draft, is taxed the highest.

For this reason it is contended that the linear rule is the best on principle. I give this opinion for what it is worth, and leave it to the mathematicians to settle.

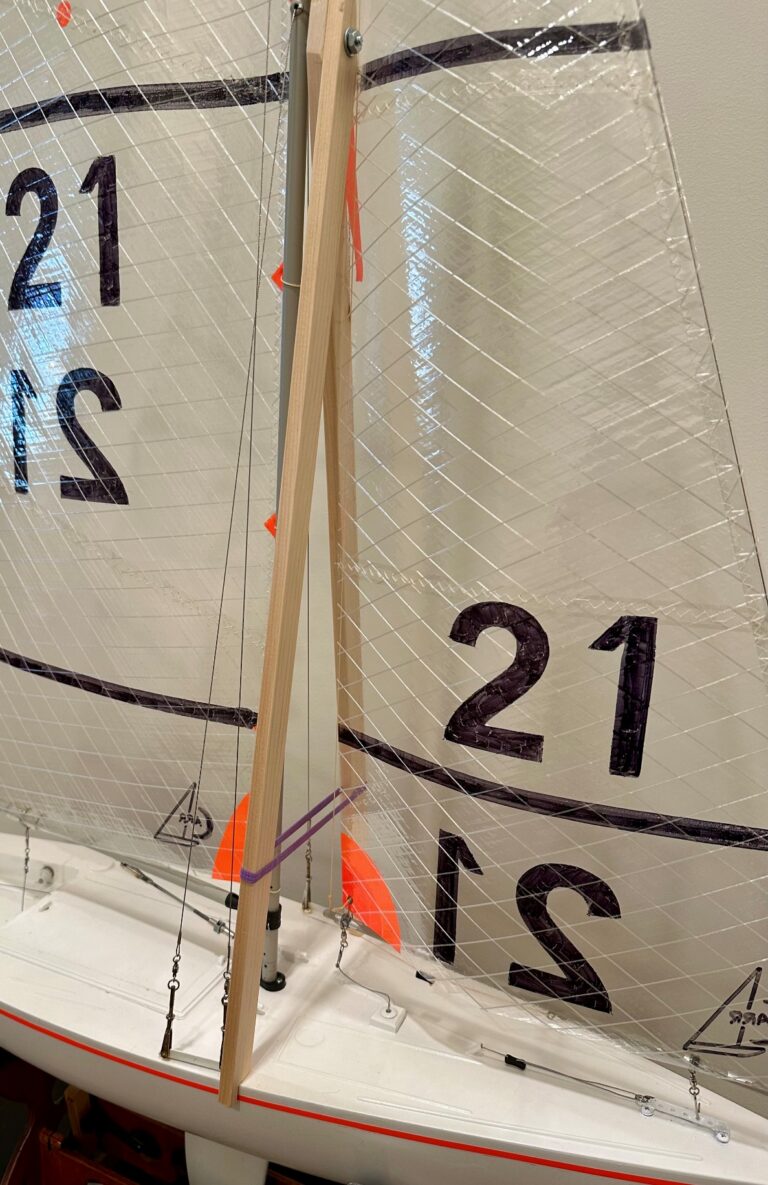

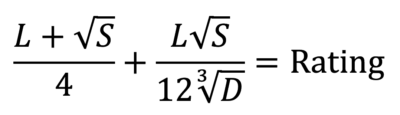

In the International A-class Model Rule* (under which the international model races are sailed) we have an entirely new principle as far as rating rules are concerned. In many rules failure has been traceable to the rule having a strong influence in a certain direction. In this rule we have two strong tendencies pulling in opposite directions. As will be seen, the formula is divided into two parts. The first encourages very light displacement, whilst the second encourages heavy displacement. The two parts· are balanced against one another and can be easily adjusted by varying the constants to correct any tendency which is considered undesirable. Having the correct length, sail and weight, it only remains to add suitable restrictions as to freeboard, draft and overhangs. One can thus obtain the type desired, and within the limits imposed by the size and type, it is possible to evolve the fastest model.

The A-class formula has now been in use unchanged for the past six years by model yachtsmen. Boats differing greatly in length, beam, weight and sail have been built under it, but in every case competition has been close between the leading yachts. Boats to-day are considerably larger than they were when the rule was first introduced, but I think that may be ascribed to designers not realizing the full possibilities at the commencement rather than to any serious defect in the formula itself.

From our examination of the various forms of Rating Rules we, therefore, draw the following conclusions:

In the case of restricted classes it would appear that if the restrictions are stringent enough to be efficacious, the designer’s freedom will be curtailed undesirably and progress retarded. On the other hand, a measurement formula used without restrictions is very difficult to draft in such a manner that it will produce the type of boat desired and leave no loopholes for evasion. In fact many measurement formulæ have produced types very different from what was intended when they were drafted.

It may also be said that the most satisfactory rating rules in practice have been found to be those where a measurement formula is used in conjunction with a set of restrictions.

My final deduction, therefore, is that a measurement formula is essential to measure size (including sail area) and that restrictions are necessary to ensure a suitable type and guard against too great a divergence in any dimension or dimensions. If this is a correct inference, then not only is the ideal rating rule possible, but it will be found to consist of a· measurement formula used in conjunction with a set of restrictions, and (subject to the limits of size and type imposed) the model evolved by competition will then be the speediest.

[In view of the discussion now going on among model yachtsmen in the United States, this article on measurement rules and their functions, by a well known British model yacht designer, will prove of interest. It appeared first in The Model Yachtsman.]*International Model A Class Formula

Note: D in this rule is Displacement.