Get Your Boy One (For Yourself)

Article and catalog copy by Peter Kelley

It may not have been nearly as inspirational as “Just Do It” (Nike, 1987), nor as unforgettable as “Finger Lickin’ Good” (KFC, 1952), but over 100 years ago “Get Your Boy One (For Yourself)” was the slogan used to promote Boucher Inc., a relatively little-known American manufacturer of model sail- and powerboats. As slogans go I think Boucher’s has stood the test of time quite well.

A quick introduction: I am Peter Kelley, US VMYG’s recently appointed Class Coordinator for Vintage Power Yachts and, for the past 35 years, a collector of vintage model yachts, both sail and power.

Because the world of model powerboats is new to the US VMYG, I will periodically write about them. I thought I would start first with this brief look at the scale model powerboats manufactured and sold by Boucher Inc., a New York City-based company that operated from 1905 until about 1950. (I have never found any actual record of the company’s demise, and certain parts of the company’s business appear to be carried on to this day by others. See Bluejacket Ship Crafters, which claims Boucher as part of its corporate heritage.)

So, why start with Boucher? Well, Boucher Inc. was more than just a “toy” manufacturer; it was founded by Horace E. Boucher (1874–1935), a college-educated naval architect who served as head of the model shop of the US Navy in Washington, DC, from about 1895 until 1905. As a result of the training and experience of its founder, the model boats later produced by Boucher Inc. were beautifully engineered, wonderfully crafted, and awfully expensive for the time. These are characteristics which have heavily shaped my collecting preferences.

While there were several manufacturers of model power- and sailboats in operation at the time in England and Continental Europe (Bassett-Lowke, Marklin, Radiguet, Kellner) Boucher Inc.’s “model studio” in New York City was unique to the US. The new business allowed Horace Boucher to continue his commercial ship modeling work (for the Navy, as well as for private shipbuilding and marine engineering firms) while mass producing ready-to-launch model power- and sailboats sold through the company’s own catalog and also through high-end toy retailers like FAO Schwartz. And, in case the finished product was too expensive for your blood (as it must have been for many, as you’ll see below), each component of each model boat was offered for sale separately or in pre-cut “construction set” form through Boucher’s catalog as well.

Boucher promoted his catalog of models through small advertisements placed in relevant periodicals, ranging from the modelmaking and model engineering monthlies that were then popular to science and mechanics magazines and, occasionally, in pre-Christmas editions of the New York Times.

Boucher’s hand is also clearly evident in the book Miniature Boat Building (Leitch, Albert C. (1928) Norman W. Henley Publishing Co., New York) which contains over 500 illustrations of “construction methodology” for a range of model sailboats and power speedboats, each of which happens to be identical in dimension and design to those offered in Boucher Inc.’s 1922 catalog. Aside from a full-page “Boucher Inc.” advertisement on page 243 there is no reference to Boucher anywhere in Leitch’s book, but I would note that all of the diagrams of the different power plants, boilers, and torches contained therein refer to each variant using the same nomenclature as does Boucher’s catalog. (The high-speed 4- cylinder steam engine is, in both cases, called the “S-74”, for example.) Personally, I believe that “Albert C. Leitch, Naval Architect” is, in fact, the nom de plume used by “Horace E. Boucher, Naval Architect”, but since I have yet to find anyone else who cares I haven’t bothered trying to prove it.

So, some focus on the line up of powerboat models produced by Boucher Inc. is in order. Most of this material comes directly from the several Boucher catalogs that I have collected over the years. Boucher Inc. did not issue catalogs annually; it did, however, send “aged” catalogs out with fresh price lists where necessary. For the most part the product offering remained substantially the same over those years for which I have catalogs, from 1922 into the 1940s. All of the products are well illustrated in a combination of line-drawing and black and white photography. In addition to the stock offerings, the earlier catalogs each offer hand-built, commissioned custom jobs, built to the plans or specifications of the customer. Although shortly after the death of Horace Boucher in 1935 this service was no longer offered in any of Boucher’s catalogs. These “custom jobs” are quite rare. In over 35 years of collecting I have managed to find only three: a 5- ft, 4-cylinder, steam powered “racing launch”; a 3-ft, 2 cylinder, steam powered “open launch”; and a 30-in single cylinder, steam-powered singlestep racing hydroplane.

Initially, Boucher offered a line of five stock model speed boats. The “entry level” version was the Minnow, 24 in LOA and powered by a Boucher-branded spring motor designed to look like the model of a single cylinder gasoline engine.

The catalog heralded the Minnow as “A Real Power Boat for a Real Boy- No Acids, Flame, Heat or Steam”- not exactly a catchy pitch, but likely quite comforting to many moms back in the day!

The catalog also claimed that a 5-min run at 3 mph was possible on a full wind up.

In addition to the Minnow, the stock line consisted of four progressively larger model launches, all steam powered. The four are similar in design and construction but with slightly larger plants and boilers as the hull size is increased.

At 30 in, the Snapper was fitted with a single cylinder plant and was designed to give the boy captain “experience in handling engines, boilers and fuel”. On a more upbeat note, the catalog states that Snapper was designed to provide a “maximum of Safety with steam Power”.

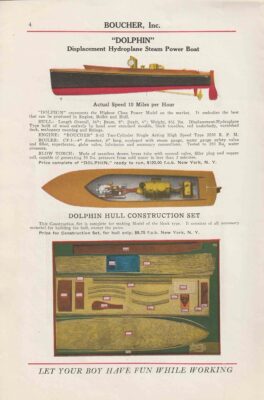

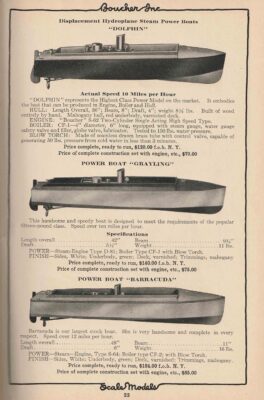

The Dolphin, at 36 in LOA, is powered by a 2- cylinder Boucher S-62 high speed (3,500 rpm) engine. In my opinion this was about the prettiest of Boucher’s designs and must have been the most popular of its powerboat models based upon the number (still relatively small) that have survived to this day. I have collected a dozen or so of this model and would estimate that at least half of all the Boucher Inc. model powerboats that I have seen have been Dolphins. At 3 ft in length, and weighing in at about 9 lb dry, the Dolphin likely represented a good compromise between speed and cost, impressive length, and ease of handling, transport, and storage.

The Grayling is the second largest of Boucher’s fleet of stock powerboat models. At 42 in LOA with a 10-in beam and bearing one of two of Boucher’s largest 2-cylinder steam plants, this was an impressive launch. I have only managed to find a couple in all my time collecting, leading me to the conclusion that this model was not produced in large volumes, perhaps because of the perceived compromise between the extra size and weight of the hull and the fact that it’s still only powered by a 2-cylinder plant.

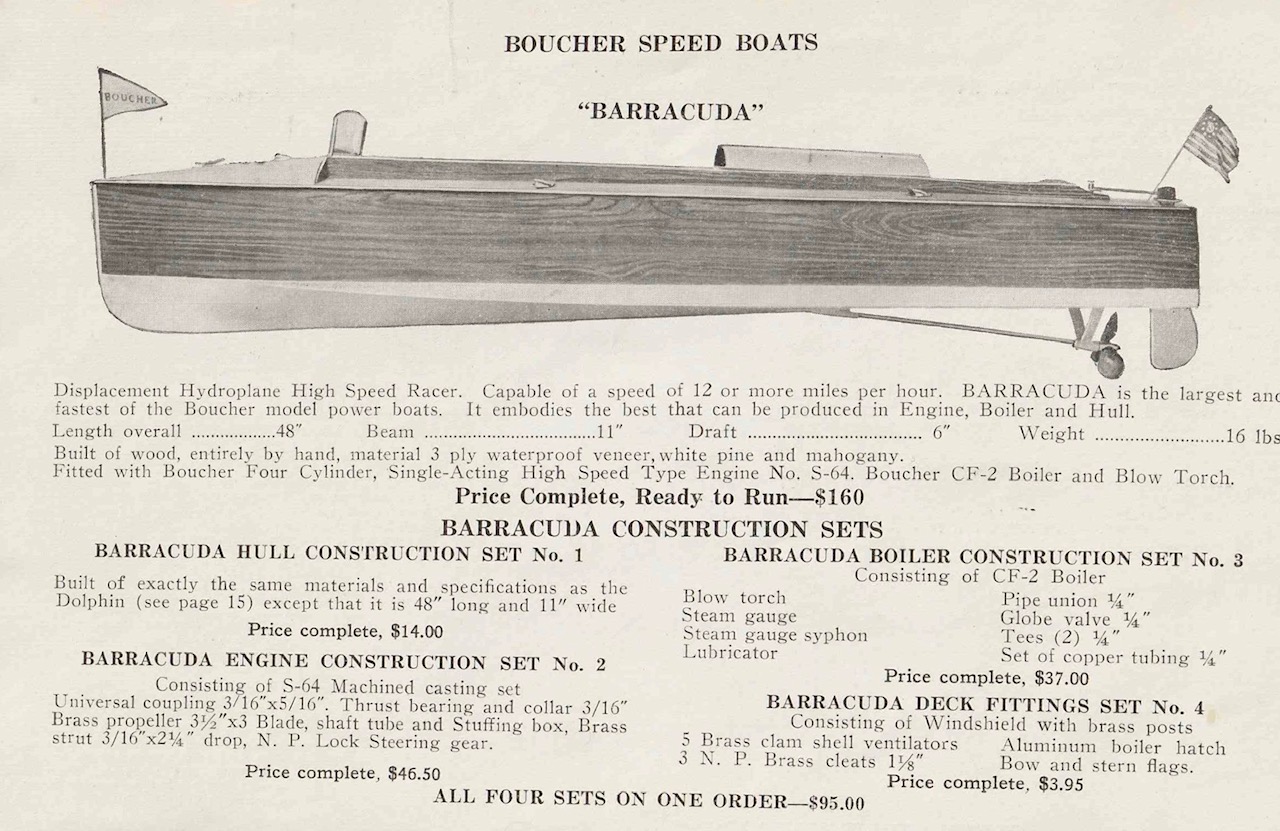

The king of the Boucher stock steam powered model launches is the Barracuda. At 4 ft in length, with a beam of nearly a foot and powered by Boucher’s unique 4-cylinder S-64 plant, this bruiser weighs in at over 16 lb. and has an advertised speed of 12 mph. The power plant is unique: literally, it consists of two Boucher Inc. 2-cylinder steam engines joined by a single 4-throw crankshaft. With an oversized boiler and large torch, it is a sight to behold. I have been lucky enough to find four or five for my collection, but they are rare in part due to their initial retail price. The 1922 Boucher catalog lists the Barracuda at $184.75. To put that in context: in 1922 a new Ford Model T runabout sold for $319.

And bearing in mind that, adjusted for inflation, $185 “1922” dollars equals about $2,750 today, “Get Your Boy One (For Yourself)” takes on a whole new meaning at that price. They are unwieldy, heavy, fragile to move, and difficult to display, but the Boucher Barracuda commands attention on display.

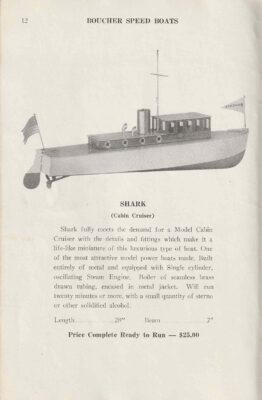

There are three additional powerboats that Boucher Inc. manufactured and sold as part of its stock line. Each filled a unique niche in the range of boats on offer. First, in the early 1930s Boucher Inc. introduced the Shark to its lineup. Unlike the rest of the Boucher fleet, which was made of wood, Shark’s 28-in hull was made entirely of heavy gauge pressed steel, and it was powered by a single cylinder Boucher steam engine. It is styled in the fashion of a cabin cruiser and is exceedingly difficult to find in good condition today because the combination of water, fire and metal has naturally left most ravaged by rust.

One of my favorite Boucher powerboat models is the quirky Polly Wog, which I believe first appeared in Boucher Inc.’s 1931 catalogue. This 24 in LOA model skiff consists of a wood hull and an aluminum deck, along with a highly unusual 2- cylinder, horizontally opposed, steam-powered outboard motor. The boiler/burner resides under the aluminum deck. and the name Polly Wog is emblazoned in gold leaf down each side of the hull. If Barracuda commands attention because of its imposing size, then Polly Wog’s allure is the “cute” factor and the unusual combination of “steam” and “outboard motor” that powers it.

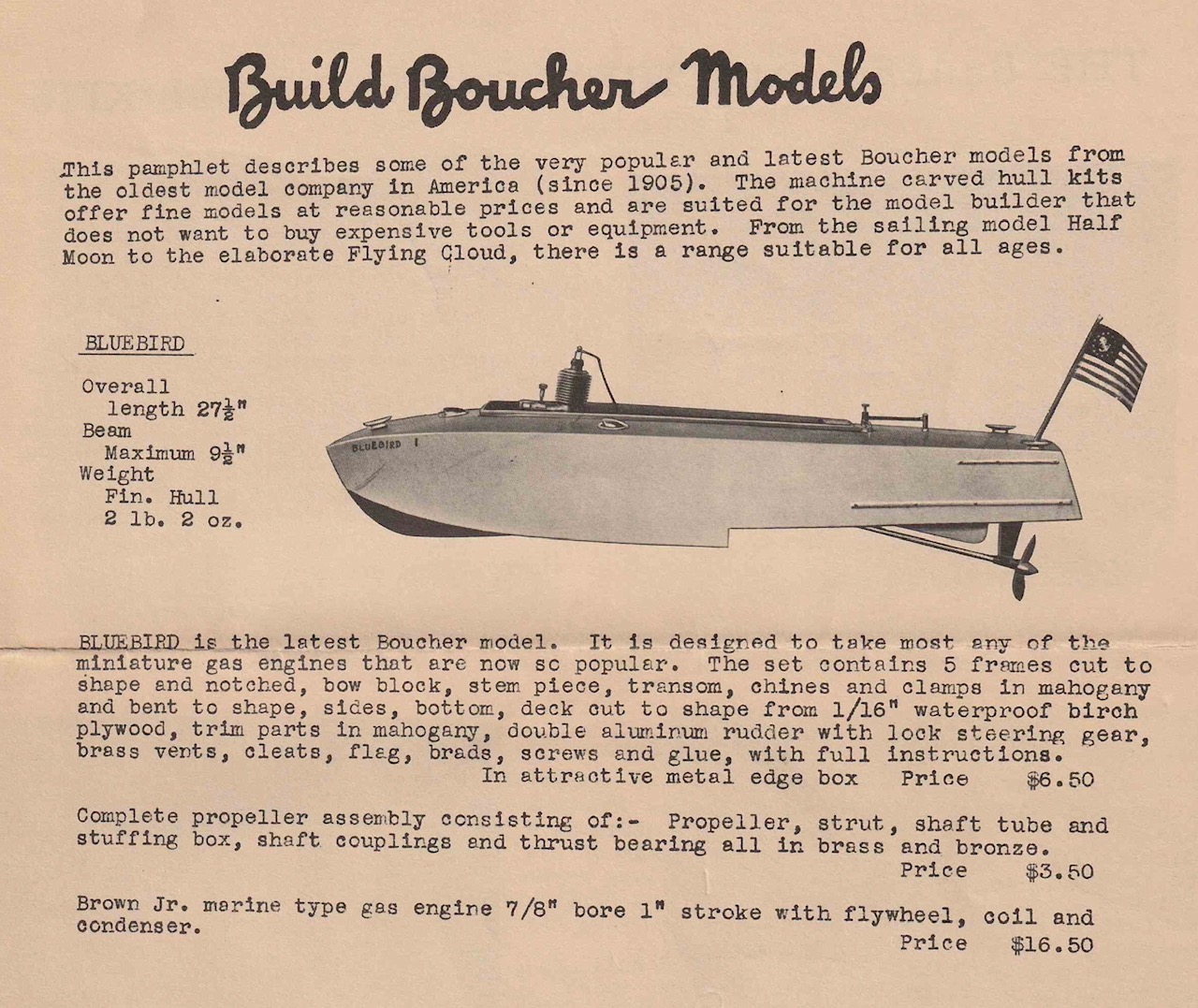

Finally, just before the outbreak of WWII, the hobby of model making was in decline and in an effort (I believe) to try to increase the failing market for its products Boucher Inc. introduced the Bluebird, a 28-in LOA single-step hydroplane made of wood that was sold either finished or as a kit (but, in both cases, without power) as an entrant to the then fast-growing hobby of tether boat racing. (Tether boats, for those who may not know, are scale model racing boats powered either by steam or gas engines and which are raced against the clock while tethered to the end of a 52 ½-ft wire attached to a pylon at the center of a shallow pond. They were run in sanctioned races in one of three or four classes. The class was determined by length, weight, and engine displacement, and, in the 1930s, the heyday of the sport, the Class A boats achieved actual speeds approaching 90 mph. Boucher Inc.’s intention was to sell the Bluebird hulls to tether racers to be powered by one of the many hobby-store gas-powered model airplane engines that were available at the time. I believe the Bluebird was first revealed in the 1939 catalog, and the timing could not have been worse. The Second World War not only seconded many young male model enthusiasts away from the hobby but the “war effort” legislation all but banned the production of hobby model engines. Very few Bluebirds exist, and many of those that do have seen heavy abuse caused by the very nature of the sport of tether racing.

A quick final note about the Boucher powerboat models: as in the case of its sailing yacht models, all the powerboat models sold by Boucher were wonderfully designed, produced, and packaged for shipment. The fit and finish were excellent, the construction was sturdy, and the designs were very appealing. All fittings were meticulously manufactured from superior materials. Each hull (and almost every component of each power plant) was embossed with the Boucher mark, or fitted with an embossed manufacturer’s plaque. And, if you were a customer back in the day who could not justify the cost of the finished product, each boat was offered as an unassembled “construction set”, by individual component, or as a simple set of plans.

So that brings me to the end of my walk through the model powerboats offered by Boucher Inc. over its roughly 40-year run. There were a few other “strays”. I have some low-production models that I can find little information on and a few “private label” models clearly manufactured by Boucher but labelled in the name of another retailer, such as FAO Schwartz. I have also collected many “hybridized” versions of these boats, boats that may have been originally bought as a set of plans, or perhaps by individual component, and which combine some obvious product of Boucher Inc. with the creative energy of some unknown modeler.

To me, Boucher Inc. represents the absolute best of the “American Dream”. Horace Boucher immigrated to the US at a young age and applied himself to his studies and his work. He achieved great success as a young man serving in a senior capacity for the Navy department of his adopted homeland. When he saw that the skills and experience gained from his effort with the Navy might be useful in private life, he started Boucher Inc. and was then fortunate enough to spend the rest of his life working at something that many of us might well have considered doing for free.

My collecting activity has slowed a bit recently, but I still actively search out power- and sailboat models bearing the Boucher brand. It gives me great joy to restore, recommission, clean, or simply inspect each of them regardless of pedigree or condition. When it comes to Boucher Inc.’s vintage model boats, both sail and power, my own personal slogan continues to be “Get Me Another”.

Peter Kelley is the US VMYG Class Coordinator for Vintage Power Model Yachts and the Canadian Regional Coordinator.