Modeling a Historic Chesapeake Bay Log Canoe

Article and photographs by John Henderson

Log canoes were work boats on the Chesapeake Bay, earning their living tonging for oysters, crabbing, and any other profitable activity their watermen owners could devise. They were, literally, built from logs. Their origins are found in the dugout canoes of Native Americans, but by the 19th century European settlers had enlarged the canoe design by fastening an odd number of logs together side-by- side, carving the outside to a pleasing double-ended shape, and then hollowing out the interior. Broadaxe, adze, and hatchet were the preferred tools. There were 3-log, 5-log, 7-log, and even 9-log boats built this way. This overly simple summary belies the complexities of the actual construction, such as the forming and shaping of the ends, the determination of thickness, and (at least in some parts of the Chesapeake) the addition of “risers” to form the topsides. The building process is well-documented in references like M.V. Brewington’s book Chesapeake Bay Log Canoes and Bugeyes.

Despite their workboat origins, by 1840 there were organized races among the log canoes, and construction of lighter and presumably faster canoes began. The Civil War ended these races. There were sporadic revival efforts, culminating in the formation of the Chesapeake Bay Log Canoe Association in 1933. Racing began again; boats were restored to “better than original” condition, and sail plans grew larger and more innovative.

Enough of these log canoes survive to this day to form an active racing fleet. I think most are of the 5-log size and are documented for historical records. The originals were built “by eye” with no drawn plans, and it is not unusual for there to be variations between the two sides. The documentation process includes creating lines drawings by taking measurements off the original hulls (presumably the preferred side of the hull). Sail plans seem to have evolved constantly and grew larger as racing became a priority, so documentation of sail plans is pretty “generic.” The boats had and still have centerboards, but these are rarely documented in the historical record. In fact, one of the few drawings that I found that showed a centerboard had a footnote saying that the location of the board was not accurate. Over the years of racing, centerboards evolved to be ever-deeper and better-shaped.

The canoes are unballasted and have enormous sail plans. They are kept upright (at least most of the time) by a large crew sitting out on long hiking boards that are moved from side to side with each tack (see Fig. 1). Hiking boards have been in use on log canoes since the mid-1800s.

Although this is an exciting way to spend an afternoon, I didn’t see a practical way to implement this in an R/C model, to say nothing of the starting line chaos caused by a boat with long boards sticking out the side. Therefore, this model has a deep fin with a ballast bulb, and the large prototypical cockpit must be sealed reliably when sailing. There is a downside to ballasting. Full-size unballasted log canoes may capsize, but, unlike inadequately sealed ballasted models, they do not suffer the indignity of actually sinking. Full-size boats cannot be self-rescued after a capsize; sails and masts must be removed before the hull can be righted. Each racing canoe is accompanied by at least one chase boat.

The model that is the subject of this article is based on the log canoe Magic, built in 1894. It is documented in the Maryland Historical Trust State Historic Sites Inventory. This documentation includes a description of the boat and its construction, along with a set of lines drawings and a generic log canoe sail plan. Magic is also documented in M.V. Brewington’s book, which contains considerable historical information on these boats.

Magic is still raced today, carefully restored and maintained.

The sail plan in Fig.1 is considerably taller than the generic plan documented in the historical record, consistent with how these boats have evolved in the early 20th century. My model, for reasons of stability and lack of courage, has a lower aspect ratio rig, which could be viewed as a compromise between the original and the current rigs, and it is likely representative of a rig at an earlier stage of evolution.

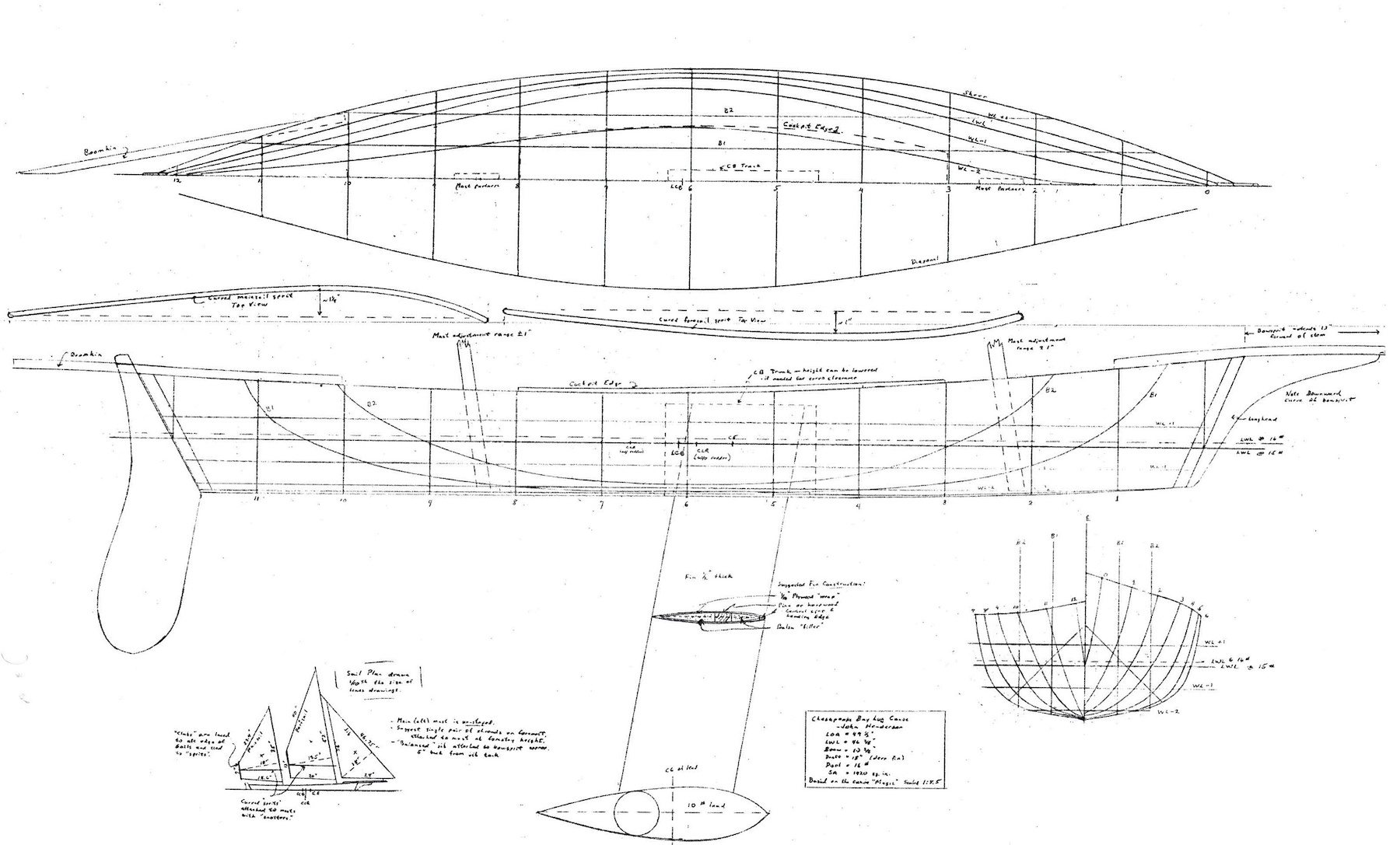

My lines drawings of the model are shown in Fig. 2.

The scale is approximately 1:8.5, yielding a model that is 49.5 inches Length on Deck. The hull is scale above the waterline to preserve appearance when sailing. Below the waterline, I have deepened the hull to provide more displacement. This departure from scale is almost always necessary in order to make a model that can sail well. I have documented examples of the scaling and design processes in several articles in this journal, and there is also a summary in the Design Articles section of the US VMYG website (see the series “Planning and Building Scale Models that Sail” under Design Articles).

The model’s major dimensions are:

Length on Deck: 49 1⁄2 in

Sparred Length: 6 ft 2 in (jib boom to boomkin)

Waterline Length: 46 3⁄8 in

Beam: 10 3⁄8 in

Draft: 18 in

Sail Area: 1420 in2

The most dramatic departure from scale is, of course, the fin and 10-lb ballast bulb. Hull volume had to be increased enough to provide the extra displacement. The increase was not as great as this statement might seem, however, because the full-size canoe has to carry almost a ton of crew (see the photo in Fig.1). The fin is 18 in deep to provide enough stability for at least moderate breezes. While this model is intended to sail in

a reasonable range of conditions, I do not suggest that it is ideal for windy conditions— and neither are the full-size prototypes.

This article is not intended as a construction guide, although the plans are entirely sufficient for an experienced modeler (and one of the author’s friends has built his own model log canoe based on these plans). Nevertheless, I will offer a few comments and suggestions for dealing with some of the oddities of log canoes and especially R/C model log canoes.

Rather than carving a hull from an assembly of large blocks of wood, I chose to build a strip-planked hull over plywood bulkheads from which the center sections were removed to create ring frames. This is not an unusual modeling practice.

A prominent feature in Fig. 3 is the centerboard trunk and its support. The slot visible in the top cap of the trunk is for the keel bolts that will hold the fin. The trunk is longer than the profile of the fin in order to allow for adjustment of the Center of Lateral Resistance, if necessary. This is also noted on the plans in Fig. 2, and it was inspired by the lack of documentation of the prototype centerboard location in the historical record. Early test sails have indicated that the location drawn on the plans is pretty good. I expect to fill in the empty space in the trunk to reduce drag from the large opening in the bottom.

Fig. 4 shows the boat with the deck installed. The side decks on my model are wider than scale in an effort to discourage flooding when the boat heels. Even with the wider deck, the cockpit opening is very large for a model, and it must be sealed effectively when sailing. I note in passing that full-size log canoes carry a designated “bail boy” (typically a young, small person who aspires to more glamorous crew roles in the future but whose services are vital in keeping the canoe afloat). The rectangular holes on the deck’s centerline fore and aft of the cockpit are for the masts, allowing adjustment of the position of the Center of Effort of the sail plan.

Fig. 5 shows the deck with the bowsprit and boomkin installed. The boomkin is the structure on the stern, which projects well past the rudder. A crew member sits on this frequently very wet perch (see Fig. 1) to manage the aft sail.

The fin is fairly deep (18 in), it must support 10 lb of lead at the bottom, and it must do so without much bending or twisting. I made it entirely from wood. I settled on the structure shown in Fig. 6, which shows the fin’s top edge and its construction. There is a full- length central spar made of pine—the two pieces of pine have the distinctive end grain pattern. Forward and aft of the pine are lengths of balsa (whose end grain appears as dots), shaped to form the foil. This foil shape is wrapped with good-quality 1/16-in plywood. A leading edge is shaped from paulownia or some other light wood. The result is very stiff; it weighs around 0.7 lb.

The profile shapes of the sails (known as “leg o’ mutton”) and the associated nomenclature are unusual, maybe unique to the Chesapeake Bay. The sails are named schooner-fashion: starting at the bow, the names are jib, fore, and main.Yes, the “fore” is bigger in area than the “main.” The fore- and mainsails do not come to a point at their clews. Rather, their aft edges are more or less parallel to their masts and are supported by being lashed to a vertical spar known asa “club.” The booms are called “sprits”, and they are usually made with some curvature to allow the sail to assume its airfoil shape. Having sail area below the sprit means that these sails are “self-vanging.” Most log canoes attach the forward ends of the sprits to the masts with an adjustable “snotter”, which can set the draft of the sail by pushing the sprit aft. The jib is attached to the bowsprit with its boom projecting forward of the attachment point at the end of the bowsprit, in a manner used by most model classes.

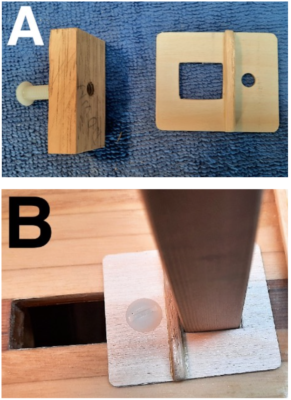

Fig.8. The mast collar allows the mast to be adjusted in both position and rake. The parts are shown in A, and the installation is shown in B.

Early log canoes had unstayed masts. Starting around 1930, foremasts acquired stays, but the main (aft) masts remain unstayed even today. The model follows this practice.

The masts are adjustable in both position and rake and are both keel-stepped. The bottom of the mast is anchored by a pin inserted into the chosen hole in a wooden beam on the keel. At deck level, I set the position with a combination clamp and mast collar. The parts and installation are shown in Fig. 8. The wood block goes below deck; the collar is clamped to this block by the screw. The mast goes through the square hole in the collar, and its position can be set anywhere along the deck opening. This provides the necessary adjustment in a lightweight and straightforward way.

Fig.9. Radio Installation. The trim server for the job is visible on the port side of the centerboards trunk (the bow is to the right in the picture).

The radio installation is fairly standard and is made somewhat easier by the huge open cockpit. I used a drum winch with a loop of line that runs around the cockpit from one side of the winch to the other. No return spring is required, and sails can be connected to either side of the loop. All three sails are adjusted together, but there is a separate “trim” servo for the jib.

The large open cockpit is a concern in the event of a knockdown, so a secure and watertight hatch is required. I like to carry models using the cockpit edge as a handle, so I wanted a hatch that could be inserted with the boat in the water. I have made a big, cockpit-shaped “plug” with slightly tapered sides and 1⁄8-in weatherstripping foam that can be inserted tightly (I hope) at dockside. Incidentally, the boat can be heeled to about 45 degrees before water reaches the cockpit coaming.

The Log Canoe plans are available in the Store under Schooner Plans.

Acknowledgements

I want to acknowledge the contributions to this project made by several of my friends and fellow modelers of vintage boats. Stan Smith, who has won multiple Craftsmanship Awards at the Vintage Nationals, built a log canoe to this design simultaneously with my build, and he and I shared many long and detailed discussions to try to resolve the unique building and rigging issues that never stopped appearing. Rob Dutton and Gary Nylander, in addition to their R/C modeling skills, have been part of racing crews on full-size log canoes, and they provided very valuable insight into the rigging and sailing oddities of these boats. Ed Thieler is recognized as a superb scale modeler of workboats of the Chesapeake and Jersey shores, and he shared his knowledge of log canoe rigging and workings. If there are bad design choices despite the guidance of these experts, those errors are mine.