On the Rigging and Sailing of Model Windjammers

by Douglas J. Boyle

Introduction

Before discussing the main subject-matter of this article a few remarks seem to be called for on the hulls of model ships. The hull of a model ship, regularly sailed, has a rough time of it. We must have a strong hull, and a sound one.

Of the three generally favoured methods of building model sailing ships–the dug-out method, the bread-and-butter method, and the building in ribs and planks, I very much prefer the first one, firstly because the result is a strong hull in one piece, and, secondly, because there is no finality about it: the hull can be refined and improved with every successive re-fit, for twenty or thirty years.

Models built in layers are for ever causing trouble under rough use; and as the real model-yachting season begins in Autumn, and ends in Spring, we must expect rough usage. My experience is that Summer sailing is a dreary business, and I maintain that model yachting is not a Summer sport, owing to the poor winds. We must build for rough usage therefore.

Models built with ribs and planks are too delicate for the clashing and banging of hard and continuous sailing. Soon broken, they are difficult to mend. They oannot grow.

A dug-out hull grows with her builder. It is likely to be better and more beautiful in shape after twenty years than it was when just completed, provided a judicious margin has been left for improvement. Every successive re-fit and rubbing down before painting gives one the opportunity to remove this little blemish in the lines, or that little stiffness in the sheer, which every builder will continually be noticing in his models, if he have any love of ships in him at all. A fine ship grows with her builder; and should continue to grow long after she has been first finished. Her master’s love of beauty in ships must have opportunity to exercise itself upon her with every seasonal re-fit: and the dug-out hull best lends itself to this gradual refinement through the years.

Into that ship, growing thus, goes the personality of her builder. She takes upon her, despite all crudities and oddities, the real stamp of genius, the look of energy, of lightness, of beauty and of grace. She becomes a living thing, organic and individual something utterly right and fitting, something that deeply satisfies.

I have a great suspicion of plans. To those who can faithfully interpret them they are well enough; and it is good that the shapes of former successes should be put on record. and be preserved. But that a man should always do his building to a plan I cannot for a moment believe. Plans of real sailing-ships embody many precautions which it is quite unnecessary to consider in the model. For instance–one example–a 2,000 ton ship is built to carry, say, 3,000 tons of wheat. Her sail plan should give her 10 knots on a bowline; and that means a head sea. It is obvious that the bows of of that ship will have to be made fairly blunt underwater, if every man jack on deck is not to be swept overboard at the first dive.

Not only that: it is not the function of the model-maker, in this case, to reproduce exactly the great ship on a small scale. It is for him rather to suggest it; and to do this he must subtly exaggerate; give his model more sheer than ever a real ship had, for instance; or sharper bows, or greater beam. Plans are meant for our guidance, for the preservation of successful examples of ship-designing, to give us an idea of what is wanted, not for our slavish imitation.

There is another point. I look upon the carving out of a model ship’s hull as sculpture, an art, as freehand drawing, where the vital thing is not mathematical accuracy but beautiful suggestion. I presume no sculptor ever worked out his statue of Hermes from section plans on different levels; and I fail to see why a model shipbuilder should be a slave of plans and water-lines. If a man has a real feeling for beauty in ships he will surely carve out of the solid log a lovely creation, without any plans whatever, provided that he has, fixed in his mind, that ideal creation, or dream ship, which every model shipbuilder ought to have glowing in his imagination.

We are told that carving from the solid log, without plans or templates, is laborious; and an old woman’s way of building. Don’t believe it! On the contrary, it is happy work; and a freeman’s way of building. As his fancy prompts him, so the builder carves. He exercises his own genius; he does not eopy the work of somebody else. He designs his ship as he goes along, trying to get this beauty here, and that point there, and my experience is–that the vessel gradually evolved in this way sails the best.

Patience and time are required, a good eye and a dogged spirit, certainly: but for hard use and good sailing, aye, and good appearance too, give me the dug-out model! Once carved out, you have it. You may judiciously alter it, and go on refining it for twenty years, and you still have something left to which you may cheerfully attach a two-inch-deep false keel, and a two or three stone lead keel; both, in my opinion, essentials to a sueeessful model windjammer of any size.

There is the rub. A model windjammer must of necessity be heavily keeled, since she carries a great deal of top-hamper in a wind. Ballast is very unsatisfactory, laborious to handle in and out of the ship; and it slides about inside the hold with every squall, despite every precaution: and you forget where you put it for that particularly good bit of sailing you onee did. Hence, a keel and keelson are necessary; and good substantial ones too. This means that strength is required in the hull; and the dug-out hull gives you that strength. You ean crash on to the rocks, or the conerete, or be crashed into by other models, without much fear of starting joints and planks.

But you must have sound hatches, with high coamings. A windjammer is very wet in a wind; and constant sponging-out on a bitterly cold day leads to corruption of language. The model needs to be as tight as a submarine on her various decks. And don’t forget the scupper-holes through the bulwarks. The ship must rid herself quickly of the deck-wash, especially in the waist. She has quite enough to do without carrying half-a-gallon of water about on her main deck. One old two-deeker I have sailed could have carried a full gallon of water on her decks, so high were the bulwarks, and so tight: and, until I pierced them for scupper holes the old ship was sadly laden in a blow, merely by the deck-wash. Little things like these ean mean a great deal in action. Ships are not yachts. Their main decks and well-decks become small swimming-baths if not given rapid clearance.

Let your ship have beam; and a full midship section. A length equal to five or six beams is amply fine enough. The depth of the hull itself apart from the keelson and keel, should be about two-thirds to three-quarters of the beam. Avoid flat surfaces and straight lines as much as possible in the carving of a hull. Go in for curves; think in curves and graceful sweeps. While the ends of the underwater body should be sharp, the mid-ship portion should be very full, generous and round, well down into the water, to give firm support to the ship; for it is obvious that if at each quarter fore-and-aft, the vessel has a good bold cheek or haunch to sit on, she will be the more seaworthy.

Be sure give her a noble sheer, or upward curve towards the bows, and a good sweep out over the water at the stem. They are the birthright of the windjammer, the noblest of sailing vessels.

Be sure likewise, when fitting the keel, to keep the ship down by the stern a little. A windjammer is peculiarly sensitive to the placing of weight on her hull. With weight forward she is for ever swerving into the wind, and going aback. She is always happiest sitting down by the stern.

The right stowing of the cargo on the old racing clippers, so that they rode a little down by the stern, was always an important preliminary to a record run. It was not sufficient that they were merely level. They had to be definitely down by the stern.

The Masts and Spars

It is well to have some idea of the placing of masts on the full-rigged ship. Though builders will generally take the mast-positions from the plan, a handy formula for the fixing of the masts will not come amiss.

The following proportions were taken from a particularly beautiful plate, and were found to work excellently when applied to a model. The placing of the masts was pleasing to the eye; and the balance obtained could not possibly be bettered. But, of course, many things besides the happy placing of masts enter into the question of good sailing.

Model Full-Rigged Ship:

A three skysail yarder, with single topsails and single topgallants.

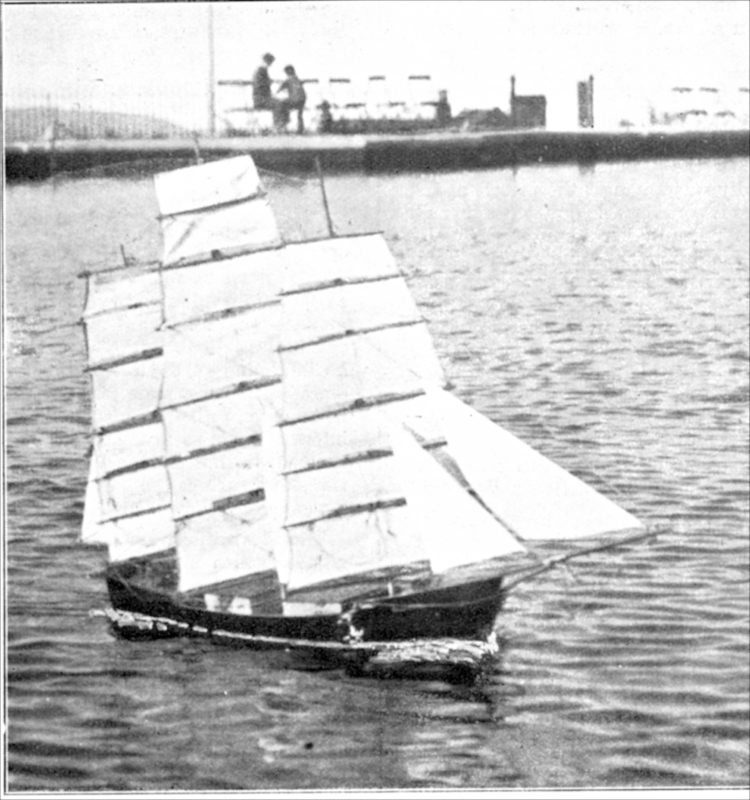

Showing method of setting stays, bowlines and braces.

Starboard side only. Staysail Halyards omitted.

A — Mizzen Yard (or Crojick)

B — Main Yard

C — Fore Yard

D — Approx midship position

E — Starboard Fore Brace

F — ” Main Brace

G — ” Crojick Brace

H — ” Fore Bowline

H1 — ” ” (hung up)

I — Channels for Backstays

J — Steering Gear

K — After Hatch

L — Main Hatch (with handle under)

M — The Stoppers to prevent ship crashing

Builders fitting out old schooners and steamers as full-rigged ships may use the formula with confidence. Some of the best sailing ships ever rigged were converted steam kettles.

Get the length of the Line of Flotation, as it would be for a side elevation. Get the half-way points of it on either line of the ship; and mark off a line across the main deck, as it may be, to join those two points. That is your Middle Line. It will cross the Centre Line of your ship, which is drawn from bow to stern.

To get the position of your mainmast, mark off from the Middle Line, AFT, along the Centre Line a distance equal to One-twentieth of the Line of Flotation. That will give you the position of your main mast.

To get the position of the foremast, mark off FORWARD OF THE MIDDLE LINE (not the mainmast) a distance along the Centre Line equal to three-tenths of the Line of Flotation. That will give you the position of your foremast.

Your mizzen mast will come exactly half-way between your mainmast and the stern rail of the ship.

You will find that mast-positions vary on different plans. Sometimes the mizzen mast is nearer the stern than to the mainmast, and sometimes the mainmast is only just behind the Middle Line. But, in my opinion, the positions given please the eye best; and, from experience, I can honestly say that they gave splendid results. It must be remembered, however, that other factors oome in–the steering system, for instance, the sail-plan, the beam, and the contours of the hull.

So far as looks go, I have seen nothing to beat the beautiful proportion of the sailing ship, from the plate of which I worked out these proportions for the placing of masts.

For good appearanoe, the bowsprit, jibboom, and flying-jibboom, should come off the bows of the ship at an angle of 21 degrees FROM THE LINE OF FLOTATION; reaching out nearly one third of the length of the line of flotation beyond the stemhead.

In this conneotion it is to be hoped that builders will avoid the wretched little stump bowsprit of the later multi-masted barques, and the depressing row of masts all on a dead level. A representation of the Freneh five-master, “La France,” lies beside me as I write; and it gives me the Willies. If that is indeed a true representation of the vessel then all I can say is — “What a horrible monstrosity !” Such a bald-headed, snub-nosed, squat, and monotonous growth was surely never seen in square rig ! Only the multi-masted American schooner can give it points in ugliness.

If we are going to build windjammers, Gentlemen, let them be the real old sailing-ships, surely the loveliest creations that ever moved upon the waters! And there need be no loss of efficiency with the beauty.

With the proportions for the four-masted barque, I have not space to deal. I can, however give the bare particulars of the mast-positions on my own barque, “CICELY FAIRFAX, ” which seem to serve splendidly, after being frequently moved farther and farther aft. They might be instructive to others.

They are as follows — stemhead to foremast, on deck, 18ins. Foremast to mainmast, 12ins. Mainmast to mizzen mast, 14ins. Mizzen mast to jigger mast, 10ins. Jigger mast to stern, 11iins. Length of the line of flotation, 58 to 60ins. The mainmast lies 4 1/2 ins., forward of the middle line.

The proportions do not please quite so well as those of the full-rigged ship; but on the efficiency there is no doubt whatever. The “CICELY FAIRFAIX” is the most consistently successful windjammer in the Scarborough Club. It should be added that the bowsprit and jibboom reach out 16ins., past the stemhead, while the spanker boom stretches 7ins., over the stern. This gives a total length, jibboom-tip to spanker-boom tip of 89ins.; too great, I am sorry to say, to allow of this vessel entering the proposed National Windjammer Races.

The weight of this barque is 92 lbs: and she draws 10iins. of water, carrying, in full panoply, over forty sails.

And now I come to the point where the old shell-backs will growl at me. I advocate putting into your ships SINGLE PIECE masts. I am sorry gentlemen; but all those cherished fittings of the sailing-ship, hounds, mast-gaps, tops, shrouds and ratlines, cross-trees and what-not, had better go overboard right away. They mean top-weight, and the sailor-like way of dealing with them is to pitch them over the side, with the Dead Horse. If you smash a mast on Friday night, it is advisable to be able to fit another by 2-30 on the following afternoon, after dinner. We shall not spoil the beauty of the ship on the water by fitting single-piece masts, and by throwing overboard the Dead Horse.

Now for the spars. Let us get back to the full-rigged ship. We have stepped some plain dowel-rods for masts. How do we place the yards, and how long are they to be ?

Start with your main-yard, always. It oan be taken as an axiom at once that your main-yard will be somewhere about twice the beam of your ship. A little less is alright; but you will find that long yards give the best results, low down.

Higher up, it is different. For prettiness, and for easing the ship, it is well to shelve in considerably. Your main royal yard can be taken as being just about as long as your beam. With these two bases, as it were, you may quickly get your yards made to the right length, the main yards first then the fore-yards; and lastly yonr mizzen yards; the length of your yards decreasing gradually as you go up.

Your main-yard hangs just about one beam up the main mast, from the deck. Your upper-topsail yard hangs just about one beam above THAT your lower topsail yard coming half-way.

Your top-gallant yard hangs two-thirds of the beam above the upper-topsail yard; and the royal yard just short of half a beam above that. If you are going in for skysails, and a moonsail on the main, you will carry on towards the stars in like fashion.

Having cut all your yards for the main-mast, get them slung on the cranes in the places they are to occupy, which you have already marked off on the mast. The simplest form of crane you can possibly have, and, in my opinion THE BEST, is simply a large brass screw eye, half an inch in size across the eye; which eye is turned to the horizontal position when screwed in.

Screw this into the mast at the right height after making a suitable hole with a bradawl. Then put a small brass screw eye bang in the middle of your yard, open the eye with your pliers, and hang your yard on the large screw eye just put into the mast. You will find that the yard will now swing round, to and fro, through a large arc, the smaller screw-eye sliding along quite easily suspended by, and inside of, the large one. If you have shaped the yard truly, and put the small screw-eye-bang in the middle of it, it will hang square upon the mast. All cranes, of course, to be on the forward side.

As you have done with the main yard, do also with the others, going up the mast methodically, using smaller screw-eyes for the cranes as the mast becomes more slender. If well done, these simple cranes, trusses, and yard-slings combined will stay put, through fair and through foul, giving every satisfaction. Yard-lifts will be unnecessary; parrels will not be needed; and all vou have to do, when you wish to take off the yard, and the sail below it, is to hook it off the crane.

The sails being attached permanently to the yards, each to its own yard, and as the sails are simply held down at the clews by strong loops which fit over the ends of the yard below, sails can easily be whipped off, or restored, when sailing.

Your fore-yards will hang slightly lower, and be slightly shorter than the main yards. The mizzen yards also hang slightly lower than the main yards at the crojick; but as they are to carry smaller sails than either fore or main mast, the distances between them diminish rather rapidly; so that the mizzen-royal yard hangs just a tiny bit higher than the main top-gallant yard.

The mizzen mast, of course, is much shorter than the main; while the fore-mast is just a little shorter than the main.

Having made your yards and slung them all on their vanes, marking them all with cuts, so that you know where they belong, you may now measure up for your sails, the HEAD of each squaresail being just one inch shorter than the yard which is to support it.

The mizzen-yards, of course, are smaller even than the foreyards, and should all diminish in size agreeably with the fore and main yards. You will now be able to measure your sails exaotly, the yards being there to give you exact measurements, and the right depth for each square-sail. It is important to get a good fit; so that when the sails shrink slightly with the rain, the whole pile of sail on each mast pans together like a thing in one piece. Flat sails, and a tight leach, mean good sailing to windward.

Rigging

Before discussing the fitting and handling of the sails, it will be well to make clear a few points about the standing rigging. As the running rigging ean hardly be discussed apart from the sails, I propose to leave it until I deal with them.

Most books on Clipper Ship Building give a very clear idea of the standing rigging required, and it is not on this part of the subject that I should be disposed seriously to quarrel with them. Except that I advise doing without side stays, or shrouds, I say go ahead with your rigging from such a book, at this stage.

But of what I consider to be really practical systems of fitting the running rigging, and working the sails, I have seen not one in any of the books I have come across. That, of course, is not to say that there is no book published which gives a simple and practical method of fitting and handling the sails. I say, I have not seen one yet.

I had hoped to deal with the sails in this article, but I find that the disposition of the standing rigging has a very vital part to play in the success of any system of rigging and sail-handling. I had better deal with it, therefore, rather more fully than I had intended to do.

I will lay my finger upon the vital point at once by saying that your lower courses will have to carry booms, or stretchers, at the foot, to simplify the working, and to enable you to point well up into the wind, with all sail set. This fact alone makes shrouds an intolerable nuisance, since these booms would rest upon the shrouds when the yards were turned at but a very small angle from the ‘thwartships or squared position. If you feel that you cannot dispense with shrouds, which add so very greatly to the beauty of a model on the study table, by all means go ahead and set them up, but you will find that when you wish to sail you will be compelled to furl your lower courses when beating to windward, since otherwise you would be continually going aback. The loose foot of the lower course of the real sailing ship is a very tedious nuisance on the model, and means quite a large amount of unnecessary adjustment when sailing.

You must have booms for simplicity of handling, and, having booms, you must dispense with shrouds,so that those booms may swing through a big arc with the yards above them.

How, then, shall our masts be stayed ? Well, I find that the backstays and forestays, with the natural strength of the mast, are quite sufficient in any weather.

Each mast will have at least three backstays — the lower mast backstay, the topmast backstay, and the topgallant mast backstay, it being understood, of course, that each backstay means a pair of baekstays, one to port and one to starboard. They should be fitted with stiff-pulling bowsies, so that they may be tightened up or slackened at will in a very few minutes.

They should hook on at either end, to the mast cap concerned aloft and to the channel or rack on deck below. Where you have so much rigging it is essential, when travelling, to be able to dismantle the ship easily. I have dismantled the ” Cicely Fairfax ” in twenty minutes, and set up the masts and rigging again at the other end of the journey, with all plain sail up, in forty minutes, and no hurry about it. Bowsprit and jibboom come off in one piece.

With single-piece masts, of course, you put a screw-eye at the places where the mast-caps would come if your mast were built up.

But it is very important that your channels, or points of attachment on deck, should be well inboard, thus giving the yards and booms ample room at all times to swing through a big arc. That is essential for good sailing to windward. You must be able to jam your yards very far round when close-hauled, right on to the backstays. It follows that the farther in the backstays ane on the deck, the farther round will your yards and booms swing and the higher you will be able to point up to windward with perfect safety.

It is amazing what a square-rigged ship can do when this point is properly seen to. Your back stays must not run down to the bulwarks, but must be right inboard, as near as may be convenient to your hatches and deckhouses. Of oourse, if your masts are wide apart it may not be necessary to take the channels far inboard; but with ordinary sailing ship proportions it is necessary to place the channels well inboard, in such a way that all the yards and booms rest lightly upon the backstays together. Your backstays then form a cushion on which the booms and lower yards may rest, thus ensuring that the yards shall at no time be pressed absolutely fore and aft when close-hauled.

The forestays are soon disposed of. They also should be fitted with hooks and bowsies for quick dismantling and tightening up. It is not advisable to have staysails and jibs running up and down on these stays, as they do on the real ship. That idea is not practioal on the model. These sails should have their own halyards permanently attached to them, with bowsie fittings and hooks where required. To set a staysail, you will then hook on the forefoot at the proper sorew-eye, run the halyard up the mast to the other screw-eye concerned, hook it on by the sliding hook, and bring it down again to the channel of that particular mast on deck. Hook it. Tighten up your bowsie, and attach your sheet to the clew of the staysail. Upper staysail halyards run down to the port channels. Lower staysail halyards, or jib halyards run down to the starboard ohannels. These ohannels will thus be your fife-rails and pin-rails also, for it is necessary that all halyards should be kept clear of the yards and booms.

Remember the old sailing ship adage .. a place for everything. everything in its place. Every separate halyard and backstay should have its own hole in the channel, held there by its own hook. You should be able to find any partioular halyard at once, even in the dark.

Now what about these channels ? It is obvious that they are a very important part of the scheme of things, since they have to hold all the backstays and halyards clear of the yards and booms forward of them, and the yards and booms aft of them. Their placing is a matter for great care and circumspection, since they can be in the way of the spars behind them, as well as of those in front. The best way is finally to place them when you have all your sails made and attached to their yards. By swinging the yards and booms on each mast in turn, you can then see just where your channels are least in the way. Of course, it is likely that these positions will be just about half-way between two masts, but not necessarily so. The channels, of course, are screwed down.

What are these channels? They are simply sheet-brass bent into angle iron, so to speak. They need to be about 1 1/2″ long on a fairsized ship, and the upright flange should stand up from the deek about 3/8″. Through this upright flange is drilled a number of holes to take the backstay and halyard hooks. The channel, of course, is placed with its length in the fore and aft direction, and it is always best to have more holes in it than you require — for emergenoies. It is the handiest gadget on the whole ship, since not only is it the ship’s fiferail, pin-rail, cleat, channel and what-not, but it is useful as a point of attachment for sundry intermediate staysail sheets.

If you make these channels of a comfortable size, with fair holes through the upright flange, you will have the less fiddling about when your hands are frozen.

Each mast will need two channels, which, of course, will lie considerably behind their own particular mast, one to port and one to starboard. It is well to have other similar ehannels on the poop and on the forecastle. They are very useful for the hooking-on of braces and bowlines. There should be no attachments outside the ship, except those for the bobstay and martingale backstays. All shrouds, backstays, braces and suchlike should be hooked on to channels or racks placed well inboard. You don’t want them sweeping away in collisions, and you do not want them to be a brake on the ship by trailing in the water when she is making heavy weather of it.

All lines, forestays and backstays, need watching on wet racing days. My experience is that they tighten up very much, imposing a considerable strain on the masts, pulling them into all sorts of queer shapes. Whether this is because I always rub beeswax into my cordage or not I cannot say, but the point is worth watching, since it can alter the sailing of the ship. It is also another and very powerful reason why shrouds, or sidestays for the masts, should not be fitted. Unless such shrouds had elastic lanyards through the dead-eyes, it would entail considerable adjustment, frequently done, to keep them taut and tidy. Like the old sailors on the windjammers, you would have to be for ever working with the handy-billy, tightening up or easing off.

This constant tightening and slackening of your rigging is another reason why it is best to fit masts in one piece.

Plenty of stays are needed under the bowsprit and jibboom, and a martingale, or dolphin striker, is advisable. These not only take some of the pull on the jibboom exerted by the many mast backstays, but they also act as shock-absorbers when you run somebody down.

Your stays being of strong line and fitted with bowsies, they give graciously. The dolphin striker should be hinged, to move fore and aft. It is best made of brass.

Wire or chainwork is of no use whatever for martingale stays and backstays. It either stretches or breaks, and looks wretchedly untidy five minutes after you have put it on. It is also nasty stuff to deal with after one of the inevitable collisions in the weekly races. You need several short and distinct stays, all fitted with copper hooks or brass ones. These hooks themselves form a distinct spring in case of collision, for they give and open somewhat; and copper hooks have this advantage, that you can have your martingale stays torn off two or three times in the course of an afternoon and yet the sorew-eyes on the jibboom, and the dolphin striker, will not be torn off, the copper hooks and the bowsies on the stays having let the ship down lightly. The hooks torn open are easily bent back into shape, the bowsies tighten up again, and away you go once more, all trim and tidy under the jibboom.

But you need also very strong fishing-line stuff, not of the brown variety, for places like this. If you wax it well and fit smooth but firmly holding bowsies, you can have your forestays torn off half a dozen times and still they are sound, the copper hooks having taken all the force of the collisions. They will be twisted into ghastly shapes, but what of that ? They are soon bent back again, and you have saved your jibboom.

Have two martingale stays forward, and three martingale backstays holding your dolphin striker back to the ship. Have a bobstay too. This holds the bowsprit down; the others hold the jibboom down. You also need jibboom shrouds, or sidestays, two on eaeh side; all stays to be made easily detachable, as on other parts of the ship. The jibboom shrouds, of course, come well back behind the cathead and are hooked on to small channels screwed into the sides of the ship’s bows, where they are now getting wide. These help your jibboom when it is crashed into from the side. It is amazing what your long and willowy jibboom will stand.

But, of course, you must not let it come end-on into a concrete wall. All ships of any considerable size or weight should have a stopper on the forecastle deck, one on each side of the bowsprit, about six inches from the bow. Against these you will ram your pole as the ship comes to land. Such stoppers are invaluable, for without them it is not easy to stop a big full-rigged ship in full career without doing any damage or carrying something away. If you miss, or if your pole slips, away goes your jibboom and the staysails attached. Thus you must have some stoppers on the forecastle deck. I use two full-size brass hinges, screwed on to the forecastle deck the wrong way over. One halfhinge, therefore, stands upright, forced back on to its partner, and so remains, and any amount of force exerted from the front will not knock it down, though you can lay it down, if you wish, in the forward direction with your fingers.

One of these hinges placed at each side of your bowsprit will make the stopping of your ship in full career an easy and safe business — a very important matter, since a ship galloping hard in a rough sea is not easy to stop. A ship cannot be swivelled round like a racing yacht, and you would run the risk of smashing your jibboom off if you did. Ships require a little technique of their own. They have too many delicate spars to be jerked round as a yacht is, and a seven stone barque like the ” Cicely Fairfax ” would take some jerking round! Thus, two stoppers, extending right across the forecastle deck, well inboard, one on each side of the bowsprit, must be regarded as essentials to the hard sailor. They will save you any amount of worry and repair work.

Your bowsprit, of course, must be exceedingly strong, though the jibboom may be light and willowy. It should be by far the stoutest spar in the ship, much thicker than your main-mast. A model ship has some terrible shocks to take, right on the nose!

Your bowsprit, therefore, should be a young billiard cue handle in strength, and should go fairly well out over the water, to give support to the jibboom, which is very slender. My opinion is that it should not be built into the ship for fear of damage in collision. I prefer to screw it down on to the forecastle deck with three big brass screws and here the dug-out ship has a big pull. She is solid and massive in this tender place.

All ships, by the way, should have very thick and strong forecastle decks. They need them badly, to strengthen the bows, to hold the bowsprit, and to hold the stoppers.

The jibboom should have a brass heel to take the screw which goes through it into the bowsprit. The only other fastening the jibboom needs besides the stays is a strong lashing or gammoning to the outer end of the bowsprit. I find that one brass screw and this gammoning — with the stays, of course — hold a jibboom splendidly.

(We venture to suggest that it would be advantageous to use a watch pintle under the heel of the rudder instead of using the form shown [above] as it would eliminate friction, Editor, THE M. Y. & M.M.M.)

Sails and Running Rigging

Square sails should be made to the exact measurements of the yards, less the half-inch at each end, and of the perpendicular height between them. They should be cut out very carefully, after being marked out on the sail-cloth in pencil. Allow half an inch for the hem and run the machine round at least three times. This gives a good stiff edge to the sail, an important matter; and it strengthens the sail. The hem serves as the bolt rope.

Avoid the selvage edge of the cloth when making squaresails; and, when cutting out staysails, get the selvage on the fore edge of the sail and turn it in as a hem, just as you have done with the other edges. This gives a stiff fore edge; and when the sail is pulled tightly by the halyard, this edge keeps the stayeail reasonably flat. Three times round with the sewing machine, as before.

The head and leeches of a squaresail should be absolutely straight when cutting out; the foot of the sail may curve gently down, just as the foot of a staysail does. When cutting squaresails, go with the material, square across the sail cloth. The sail will then machine up very nicely.

Staysails and jibs seem to give the best fits when they are cut with a slight bulge outward on every side. When such a sail is then strongly hemmed it lies as flat as a board after setting.

As windjammers’ sails take some making and fitting, it is well to make them of strong material in the first place. If you ean get the experience and assistance of the Lady of the House on this point, it is well. It is better still if you make your own ship from keel to truck. Every yachtsman should be as handy as the sailor himself, with a needle. I cut out, machine, stitch on hooks, and bend onto the yards, all sails. It is a tedious job, of course; but the delight of getting a good fitting suit of twenty or thirty sails on a windjammer is something worth taking a little trouble to have.

Each squaresail must be sewn to her own yard permanently, for hard sailing. A sort of marline-hitch-threading, with stout waxed button thread, seems to work well, and gives the roband effect of the real ship. You had best take a browse among the books on Seamanship in your local library. You will pick up a good many useful hints and ideas on rigging and knotting there. You will also get a fair idea of the style of a windjammer, from photographs of the real thing. One of the best books I have seen was by an American, Reisenburg, I believe, “Standard Seamanship.” That book gives one of the clearest descriptions I have ever read of the tacking of a windjammer.

But, of oourse, you have to make hay of all that. The original grass wi11 be very different from the hay you have to make for your own purposes. There will be no Flemish horses, foot-ropes, yardlifts and clew lines on your ship, for the very simple reason that you do not need them. What is not needed is discarded by the sailor. Your clew lines should be mere loops sewn onto each clew of a squaresail. These loops fit over the ends of the yard below.

I do not fit halyards to the yards. They are unnecessary. The yards hang quite well on their slings and trusses, in other words, on the screw eyes previously described. When you do not want the squaresails, you simply take off the loops at the olews, unhook the braces, and lift the yard out of the truss.

The mention of the braces brings me to the working of these many yards.

Let it be understood at once that is absolutely hopeless to attempt to manage the model as the real ship is managed. You are sailing a great ship without a single man on board. All thoughts of the procedure on a windjammer therefore; — “Fore bowlines! Raise tacks and sheets! Weather main, lee crojick braces! Mainsail Haul! Board! Fore braces! Ease the spanker! Board tacks and sheets! Steady!” will have to be forgotten. The prinoiple to be held in mind on the model is this; that your sguaresails, be they six or twenty, must work as one sail! There are but two squaresail tacks on your ship viz. — the port fore-boom tack; and the starboard fore-boom tack. The forward lower corner of each of the lower courses is pulled forward by what is the brace of the boom ahead of it. A tack pulls forward, a sheet pulls aft, and it is possible to argue that this brace is a sheet.

It will now be advisable to explain that all the yards are hooked by bowsie lines together, and the booms of the lower courses also.

They are braces only in the sense that they brace one another together. Your real braces are all on the mizzen yards, for they run down to the channels on deck, thus holding the whole set of yards in place that is — when you care to use them. They are seldom needed!

In like manner, for working to windward, your bowlines, holding the yards forward on the weather side of the ship, communicate their action from the fore yards to the after yards and unlike the bowlines of the real ship, they are all attached to the foreyards, and not to the leeches of foresail and of fore topsail only.

It must be clearly understood that it is not always necessary to fasten down onto the deck any of the real braces or bowlines. The yards on the three masts being strapped together, fore to main, main main to mizzen, all the way up the mast, each by port and starboard braces hooked on at equal distances from the cranes, they all move round together, and, if there be a wind abeam, you can sail for hours without ever once fastening a brace down onto the poop, or a bowline down onto the bowsprit, the wind itself jamminq the yards onto the backstay, and holding them there; In these circumstances, a windjammer is easier to sail than a yacht. All you have to attend to is the flicking round of the yards with your walking stick, at the end of a run, and the setting of steering gear, or of the spanker.

That is the state of affairs when reaching — the ideal point of sailing, for a model windjammer, far more so than running before.

When running, of course, it is advisable to square the yards a little, but not dead square. I have not seen a ship yet that will run dead before the wind. Very far from the run being the windjammer’s favourite point of sailing, it is just about her worst, if acouracy on a target be anything to go by! Of course, a nice quartering wind is another matter. A wind on the quarter is the windjammer’s joy; but entailing as it does a close-haul back again, on the return journey, it is not such a care-free business for the yachtsman as the plain reach. You must get your bowlines on, forrard, to come back again, though you can run down without fastening any braces at all.

When beating to windward, you will need to fasten forward all the fore mast yards on the weather side. To do this, you reach down the fore tack first, which is hung on a screw eye on the fore yard. The hook of this tack you fasten into a screw eye on the bowsprit. All bowlines and braces having bowsie tightening arrangement it is easy enough to get the yards set to the angle necessary.

Then fasten foreward the fore bowline, likewise to a screweye on the bowsprit. This bowline is attached to the fore yard; and when not in use, it is hung up somewhere, say on an eye in the topsail yard.

Your topsail yard will likewise have its own bowline on each end of it port and starboard. That is fastened into a sliding ring, like a bowsie, on the fore skysail pole stay, which runs down to the end of the jibboom, in this case. This stay is very handy indeed for the holding of the upper bowlines for the fore topgallant, the fore royal, and the fore skysail — bowlines are all hooked onto similar rings placed higher up the stay, at, roughly, their own level. This keeps your yards close-hauled, and firm in a jerky wind; and, even in a steady wind, if the yards were not so held, they would all fly aback directly you got rather close to the wind.

It is not necessary to hook on all the bowlines, even on a stiffish close-haul. For moderate slants it is quite sufficient to use only the fore bowline (the fore-yard bowline), and the fore tack, (which holds the fore-boom forward). These, of course, communicate their motion to the yards and booms on the main mast and tile mizzen mast, through the braces which connect them all together.

You need seldom use your real braces on the after side of the mizzen yards. You often run before the wind most accurately if you run with yards in the moderately close-hauled position, the squaring of your yards apparently leading to a good deal of yawing about from side to side, in a fresh wind. The fore bowline will do for that manoevre. It merely holds the yards steady; which is all you want. Your fore bowline is the maid of all work on the model windjammer.. You may be able to sail for days using no other bowline, and no mizzen braces whatever. You can, of oourse, quite safely run before the wind with your yards swinging loose, held together in one compact body by the intermediate braces which run between foreyards, mainyards and mizzen yards. There is little danger of you going aback; and the yards adjust themselves to a balance with the steering gear, squaring off, or close-hauling as the wind-pressure decides. The head of the ship being off the wind, and the rudder keeping the vessel down-wind, you oan gallop away to your heart’s content without a single fastening to the deck, or to the bowsprit.

It might be as well to remember that the more sail you carry the more you yaw about when running down-wind; and, conversely, the more sail you carry, the better you can sail to windward; that is, of course, if the strength of the wind allows you to crack on sail. If you are running with a pile of sail up, it would seem best to close-haul your yards, and put your helm hard up. You then get a balance of forces between the tendency of the ship to broach to, by swinging to windward, and the tendency of the rudder to pull the the ship off the wind, thus bringing her by the lee, as the sailor would say. The resultant course is a beautiful steady hard gallop down-wind, with the wind coming over your weather quarter. I am afraid the attempt to make a square-rigged ship run dead before the wind is doomed to failure, if you have stepped your masts for good beating to windward. In a light wind you can run before. In a hard wind, it is very difficult, though of course, it is quite easy to sail down-wind with the wind, say, two or three points off your tail. You oan sail a beautifully straight and steady course then.

And that brings me to the question of the steering. The Iversen wind-vane steering-gear has been recommended for use on model windjammers. Frankly, I cannot see that gear working well on a hard-sailed windjammer; and furthermore, it would give me the blues to see a wind-vane on the poop of a sailing ship.

In very light airs, and in gales, the wind-vane steering would be hopelessly impotent. It stands to reason that, if the gear is used when following a yacht in a rowing boat, it is evidently only used in quite moderate weather, since a canoe or rowing boat, cannot be of much use in a gale.

Further, the windjammer being fitted with a long keel, to keep her steady when beating to windward, it oannot possibly be as easy to steer as a light and pivoted Class racing-yacht. Considerable power is wanted on the helm; and a wind-vane of sufficient size would be an utter absurdity on a sailing ship.

I can imagine the Braine steering working fairly well, though it must be remembered that the spanker of a ship will have comparatively small power to put into the quadrant, being a small sail, when compared to the total sail area. It might be possible to work your quadrant from the mizzen yard, however, and thus tap the power of all the sails on all the yards: but I have never tried it.

I have always used my own steering gear, vastly preparing it. It may seem homely; but it works. That is all you want.

I have found it best to use a weighted rudder, a variant of the old-fashioned swing-rudder. A rudder shaft is fitted; and it comes through the counter to the poop deck. The blade of the rudder is, of course, permanently fixed to the rudder shaft.

A pin passes through the rudder shaft and this rests easily on the top of the rudder tube through the ship. Thus, when no power is applied onto that pin by any steering apparatus, the rudder is free to swing, being purposely made to fit very easily.

Now there is no rudder in the world which works better than a swing-rudder when correctly weighted. It has an easy, gentle action. It strokes the water, and gives graciously. For hard galloping and straight running, there is nothing to beat it, for it does not bite the water, it works naturally, and it seems to get your ship to the same place every time, provided the wind remains steady in force and in direction.

On a windjammer, this rudder must have sufficient lead put into the blade to keep the ship running well down-wind without bringing her by the lee, that is to say, without pulling her right off her course, to turn her tail to the wind, and bring it onto the other quarter. This experiment must be made in a fresh wind with a nice pile of sail up. When you have got the rudder-lead filed down to the correet weight for keeping the ship running straight, well down-wind, stop; and treasure that rudder as if it were made of gold. You have the secret and instrument of good sailing on nine-tenths of running courses.

You must then find out what the ship wants for all courses up to a stiff close-haul, using, of oourse, the same rudder.

For moderate runs, and reaching, you will have to lighten the pull of that rudder. I use elastic for running large and for reaching, the tension on which is capable of variation. For beating to windward I use a metal spring, the curtain rod stuff. These are hooked onto a tiller bar, which is secured to the pin through the rudder shaft. The great beauty of this system of steering is the handiness of it. To run, you simply cast your rudder loose; to beat yoU hook on the spring; which keeps the rudder reasonably central. A better device would be a locking-screw through the rudder-tube, to jam the rudder shaft in the central position. I have never used such a device; but it would be very useful on a windjammer.

By fixing two tillers, one forward, and one aft, of the rudder shafthead, vou get a balanced flywheel effect; and inorease the easy swinging qualities of your rudder.

If, then, you wish to try out further experiments in steering gadgets, it is quite easy to do so by means of these two tiller bars. You may try out something on the Braine steering lines; or you may haply attach your spanker sheet directly to the tiller bars, to one, or to both; in such a way that the angle at whioh your spanker-boom is set bears some sort of constant relation to the angle at which the rudder is to lie. In other words, your spanker can be your wind-vane.

You may thus have the advantage both of the old swing-rudder steering, and of the modern boomline gears too, since your tiller bars form a kind of quadrant, and, again I repeat, no sailing is so delightful as that whioh comes with the use of the swing-rudder. The balanced rudder idea may be old-fashioned, and worked out, on racing yachts but its period of usefulness on model windjammers is only just beginning; for it is eminently suitable for them.

It is easy to handle in bitter weather, on wild days and on calm days; and it suits the long-bodied windjammer to the nines. As there is plenty to do with the bowlines when sailing, you do not want to be troubled with a tricky and complicated steering gear. It is a grand thing to feel that you have only to whip the ship round, cast off the bowlines, cast off the rudder spring and then be sure of the vessel galloping hard down-wind again, without any fear of broaching to or of bringing by the lee. The windjammer loves the swing-rudder and seems to put on another half-knot because of it.

The Sailing of the Ship

When the rig of the model windjammer is mod)fied as I have suggested, the constant sailing and racing of it is quite a practical proposition. I am accustomed to racing with one, fair or foul, two or three times a week all through the winter. It is exercise.

Builders mechanically inclined could certainly vastly improve upon my gadgets. I have reduced everything to the simplest form on my ships; and moreover I build very heavily. Even so, I get along quite well; and without a windjammer my interest in model yachting would be nil, so far as racing sloops are concerned. There must be very many more like me; and, if they once started sailing model ships, they would find a new and immensely fascinating interest in model yachting.

But it is bound to be rather a disappointing business at first. You see, if you want any racing at all, and regular racing is the salt of the Game, you will have to race against highly specialised racing sloops in most places.

That is a tough proposition of course. You are pitting the steadiness and reliability of the squarerigger against the speed and erratic brilliance of the racing yacht; and you are bound to take many a crushing defeat. As a general rule you can only beat a modern racing sloop by your accuracy upon a target, and profiting by the mistakes of your opponent.

You will nearly always be sailing up and down courses distinctly unfavourable to the windjammer, close-hauled or running free, whereas the strong point of a ship is her accuracy and beautiful sailing on the reach, with the wind anywhere between two points forward or two points aft of the beam. In such circumstances her landfalls can be absolutely devastating to a fore-and-aft vessel, since, if the latter has to tack after missing the port, she may easily lose whatever advantage she has enjoyed in speed and handiness. A windjammer will sail for hours to and fro along her tracks, with the greatest reliability, so long as the wind remains steady in force and in direction. I find the full-rigged ship sails better than the four or five masted barque.

The Eileen O’Boyle

The lines of this little ship, which Mr. D.J. Boyle considers his masterpiece, are published in The Model Yacht Volume 14 Number 3, Winter 2010-2011.

Make no mistake about it, a model ship sails magnificently. The difficulty lies in getting the right settings for the day and the course, you have so many points to watch. Any one sail of your twenty or thirty may make a vital difference. You are always having days when sail has to be taken in. That means a different sail balance!

The rake of your masts, the tightening of your rigging in rainy weather, bad swirls over the pond, in certain places, can bring disappointing results.

Again, you are always having to sail courses on which the sail-setting for the outward journey should. by rights, be very different from that of the return journey. To save time, and because of a short course, you make a compromise, sailing both ways with the same sail set. The ideal setting for either way may be very different from your compromise. That is one of the reasons why I say that reaching is the windjammer’s best point of sailing. You can get the proper sail set, and it serves both ways.

A model ship’s most accurate course is to windward. She can be deadly on that point, on all courses up to her limit, and it must be remembered that a square-rigged ship can do some amazing sailing to windward under suitable conditions. Her many spars may militate against her rapid transit to windward on most days, but I have seen windjammers overhaul and pass 10-raters on a stiff climb when the latter have not been quite suited with the day or with the sails they were carrying. A square-rigged ship, scientifically constructed by a Master, in the hands of a skilful man, could give the majority of 10-raters plenty to do to beat it.

In a steering competition pure and simple, a windjammer would often beat a sloop, hands down, being a much more steady sailer. Even in the modified form of the steering competition used for racing at Scarborough, where the leader of a pair of racers takes five points and the other boat three points, (if both of them cross the line), windjammers often do well despite the fact that they have often to take the three points only for their accuraey.

Of course, if the faster sloop misses the line and the slower ship crosses it, the latter becomes entitled to the full five points, only one shot at the target being allowed. The rewards on the return journey being precisely the same, the boat good at running has a chanoe to shine also. All types of boats can sail with some hope of winning, and the first eight oompetitors may finish with not ten points between them, all lying one, two or three points ahead, or behind, one another. No starts are necessary, and no handicapping is oa]led for. The little boat and the big boat oan sail together in harmony, the fast and the steady. Everybody can have a sail. You can get through a big field of competitors in a short Winter afternoon. The Winning Lines by the way are twelve yards long. The pond is seventy.

On smallish ponds this system of racing oan be highly recommended, singe it keeps every man in the Club oocupied, and prevents the damage and annoyances of indiscriminate sailing on Saturday afternoons. You may sail a Chinese Junk and win the Cup. Needless to say the ten-raters being in the vast majority and the speediest vessels, do the best.

This system of racing would be very good for windjammer oompetitions. It is racing from one port to another on one tack. There need be no handicapping. The big and the little could race together and the prize would go where it ought to go, to the man who can best handle his vessel, and not merely to the fast freak ship. The variation in the direction of the wind throughout the contest would provide quite sufficient tests of weatherliness, the course being a moderate slant to begin with. A model square-rigged ship can sail up to four points off the wind in a nice cheeriul breeze and that would have to be the limit of close haul. You can go higher but there is always the danger of going aback. In a true wind you oan point very high. This forms an exacting test and perhaps it would be best to have tacking where time allows of it, since flukes of the wind might lead to disappointment.

Under M.Y.A. Rules, a man would have to try to get to the windward side of the winning-line, if he mistrusted his ability to make it in one shot. A windjammer is very easy to wear down-wind but not at all easy to box-haul up to a weather winning flag. Personally, I should tack off boldly rather than try to box-haul a few yards to windward. As for swinging round in stays the ship cannot be given the essential motion to swing her round and get out of stays and the necessary push-off would soon lead to disputes in a competition. Boxhauling by the way means making a stern board.

I am inclined to favour a tacking system of racing for windjammers on a big sheet of water, with the winning-lines at each end at least one-sixth in length of the total rum, or as near to that ratio as possible. This would obviate a good deal of miserable scraping about at an extremely rough, or extremely calm end of the pond, trying to put a square-rigged ship into a narrow goal, which whirls and eddies of wind may make utterly inacessible. You see, a windjammer sails beautifully in true winds, reasonably true winds, but can make little of down-draughts and eddies under a bank.

But whatever sailing system a man will have to race under with a model sailing ship, he had best always practise by trying to get his ship between two flags, at one shot. This gives you some idea of the settings necessary to do a definite course, with winds of definite strength.

If you known fairly well what your ship can do and what she will by no means do at any time, you will not feel so strange on foreign waters when you visit another club.

Make no mistake about it: the model windjammer can be a magnificent sailer. It is high time she had a turn.