Model Yachts: How to Design and Build Them

Part I: Designing — Sheer Plan — Half-Breadth Plan — Body Plan — Centres of Gravity and Displacement

By way of preface to those readers of Amateur Work who can’t think what people can see in such “childish amusement,” I will just say, what, no doubt, they have seen pasted about in a good many streets, ”Try it” and if their first model is one that they can pit against existing ones with success, and if they can make her go where they will the first time she is put into the water, I will say they are right, it is a childish amusement; but until that is done, I must still hold on to my opinion, that model building and sailing is as scientific and amusing a hobby, combining both in and out- door pleasure, as can be found. “So, there,” as the tender sex have it. And now to work. I shall take it for granted that you know how to make a mechanical drawing, since it has been explained in this magazine, for before you can attempt any- thing in models you must draw them out.

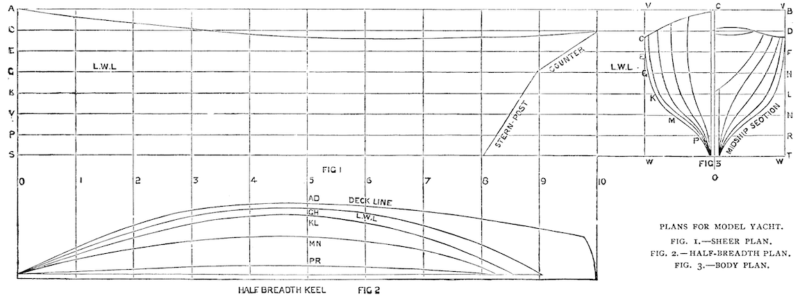

There are three plans of a model to be drawn out. Firstly, the sheer plan; this represents a view of the boat when looking at it directly from the side, as shown in Fig. 1. Then there is the half-breadth plan, which is a view of the half of the model (Fig. 2), looking at it from underneath. And, thirdly, comes the body plan (Fig. 3), which is the view from the front on the left half of the plan, and the view from behind the model on the right half.

We must begin with the sheer plan. The shape of this depends in a great measure upon taste, but for the first model it would be better to keep to the illustration shown here. Having selected a sheet of paper, to take the full size of the model if possible, (if not you will have to draw to scale), and glued or pinned it on the board, draw at about 6 inches from the top a line right across the paper, and draw it pretty heavily, for you must work all other lines from this one. Mark this on each end L. W. L., which means load water line, and is to rep- resent the surface of the water, when the model, with all her rigging, and quite complete in fact, is stationary in the water. But, before going any further, you must determine upon the dimensions your yacht is to be. A very good size is 2 feet 6 inches over all that is to say — from stem to end of counter, and, as many model yacht clubs adhere to this size, I should, I think, follow their example. The beam, or breadth, should be about one fourth of the length. Fancy dictates here in a very great measure, as it does in a great many things in model yacht building. Some like a broad beam and some a narrow beam; but experiencia docet applies here very well, and as most probably you are without experiencia, keep to the “4 to 1” dimensions. I should therefore make her 7 inch beam, so as to keep to an even figure. Now for the depth below the water line, take about one-seventh of the length, that will make it 4 inches deep. This is merely to the bottom of the wooden part of your model, and does not include the lead keel, which will come on afterwards. For the height out of water you must study circumstances a little. You see, to make a boat look pretty, there is always a certain amount of what is called “sheer” given her—that is to say, a certain curve beginning high at the bow, falling towards the centre, and then rising again at the stern. Therefore you must have a fixed dimension for your height above water at the stem and draw in your sheer according to fancy afterwards. Then again too high a stem looks bad, and moreover is apt to hold the wind and retard the boat’s speed, whereas too low a stem does not afford sufficient support to her if she has a press of canvas on. I think about 3 inches for a 2 feet 6 inches model is very fair, and the sheer you must determine yourself, or take it from the diagram here. Now you may begin drawing out in earnest. Parallel to your load water line draw 4 lines below each other, each 1 inch apart from the other. The lower line will then represent the bottom of the keel, 4 inches below the waterline. Now draw three lines above the load waterline, also 1 inch apart. The top line would then represent the deck line if the deck were without sheer, but now simply represents the 3 inches at the bow.

These lines will represent so many planes cutting the boat parallel to the surface of the water.

The next thing to draw in is the stem, or bow; keep this about a couple of inches from the edge of your paper, and never mind, for the present, the curve at the foot. Simply draw a straight line vertical to the load water line. Now, at distances of 3 inches, draw lines parallel to the bow—that is, vertical to the load water line, to the extent of 30 inches, which will give you eleven lines, and ten spaces of 3 inches each, which will be the exact length of your model. The counter, or over- hanging part, should be about 3 inches, so draw that in to your own fancy, and consult your fancy also on the “rake,” or slope of the stern- post, which should have more or less rake to allow the rudder to swing easily, of which more hereafter.

The body plan is drawn on the extended horizontal lines of the sheer plan, and the half-breadth plan on the extended vertical lines of the same.

Now, there is one part of a ship, looking at her endways, which is larger than any other part, and, past which no other part of the vessel is visible: this is termed the “midship section,” and is represented by the outside lines in the body plan. We intend making the midship section on the line 5, which will be rather abaft the centre of the load water line. Some builders prefer a long “entrance,” which necessitates having the midship section far back; while others like a short “entrance” and a long “run,” which means hav- ing the midship section well forward, so that the bow lines converge at a greater angle than the stern lines. Now draw a centre line, XY, on the half breadth plan, and on 5 mark off from XY 3 1/2 inches, which is the half- breadth of your vessel. Above XY draw a line parallel to it, and at a distance of 1/4 inch, to represent the half-breadth of the keel, and then with a thin spline or batten draw in the deck line on the half-breadth plan to pass through the dot on 5, and fall nicely into the keel line in front, and rounded at the stern for the counter. You had, for the present, better keep as near as possible to the diagram shown here; but when you get a little more accustomed to drawing in these curves you will be able to judge for yourself if a line is what, in shipbuilding parlance, they call “pretty.” Leave the half- breadth plan for a’ little while, and on the body plan draw a vertical centre line, O O, and on each side of it draw lines at 1/4 in. distant, and parallel to it, to represent the keel. One part of this body plan, you must remember, is the forepart of the vessel, and the other half the after part. Now on the load water line, still in the body plan, on each side of the centre line mark off 3 1/2 inches, which is half the beam, and, starting from this point, draw in by hand a curve somewhat similar to the one in the diagram, and see that there are no “lumps” in it, and that it falls nicely into the straight line of the keel at the bottom. Having rubbed this out and put it in again several times till satisfactory, rub it nearly out once more, and put in definitely with curves, so that you have a definite spot where the curve crosses each horizon- tal section. Do this on each side of the centre line O O. Go back again to the half-breadth plan, and with your dividers mark off on 5 from XY the places where the midship section, which you have just drawn in, cuts each of the horizontal sections—that is to say, the distances from O O to C, to E, to G, to K, to M, and to P.Through these points, or rather through the point G firstly (which is the load waterline), draw a curve to the bow, and to line 9, taking care to make it fall nicely into the straight of the stem and stern posts, the thicknesses of which are represented by the line above XY. You must be particularly careful to draw this curve in nicely since all the other lines are worked from it, and let me impress on you that india-rubber is, in the present state of the market, a cheap article, therefore you need not be afraid of wasting it by rubbing the line out again, if not to your fancy. There must be no “lumps” in the curve, and no sudden rise or fall; it must all be gradual. To find out if the line is “fair,” you need only look along it, with your eye nearly on a level with the paper, and any little inaccuracies will at once become perceptible. Having “faired” this to your satisfaction, mark off from O O (in the body plan), on the line G (the load water line), the respective distances from X Y (in the half-breadth plan), to the points where the curve, which you have just drawn in, cuts the lines 4, 3, 2, 1. Treat the after part of the load water line in the same manner, but mark it off on the right-hand side of the body plan.

Now draw in the other curves in the half-breadth plan through the points already marked on 5, trying to keep them as little hollow as possible. These lines you must simply guess at to begin with, but after a little practice your eye will tell you very nearly where to draw them in. After this is done, mark off from O O on C, E, G, K, M, and P, the distances from X Y, along 4, to where the curves C, E, G, K, M, and P, respectively cross 4. Through the points thus obtained draw a curve, and if the curve thus drawn falls in nicely, with- out lumps or kinks, your lines in the half-breadth plan will be pretty nearly right. Treat the lines 3, 2, 1, on to the left-hand side of the body plan, and 6, 7, 8, 9, on to the right-hand side, in the same way, and if each curve comes in nicely your lines will be right; if they do not fall in well, you will have to alter the “waterlines,” as they are termed, in the half-breadth plan, until the body lines can be faired easily.

It will, I am sure, entail a good deal of rubbing out and putting in again, before your lines will come right, but do not be afraid of that, since it makes your work much easier when you come to the wood-working part of the business, and do not say to yourself, “Oh! bother it, I can’t get that right on the drawing, but it will come in all square in the wood.” It is a fallacy, I can assure you; you would never have been more mistaken than when you said that. If your drawing is not correct, your wood-work cannot be correct, and therefore you will be guessing at things all through the job, instead of having everything down on paper in a respectable manner. So put that notion out of your head, and say it must come right in the drawing, and when it is right you will be a great deal more satisfied with yourself, I am sure.

You have not yet, by the bye, drawn in on the body plan, the sheer, therefore measure off the heights from the load water line to the sheer in the sheer plan on the various lines, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc., and mark them off on their corresponding lines in the body plan, and the distances from O O to 1, 2, 3, etc.; you will take, of course, from X Y, in the half-breadth plan, to the deck line along 1, 2, 3, etc., there. Having joined the points thus obtained with a nice curve, I think your drawing is finished. The keel you can only put in afterwards, when you know the weight of lead your boat will carry, which will be more or less, according as you have made your lines “fuller” or “finer.”

In the next paper, then, I shall begin with the building of the model; but before we come to that, a few words on the shape of models would not be out of place. Models must be considered as racing yachts, and, therefore, unlike merchant vessels, carrying power, or rather “cargo space,” is no object. The great thing in models is to get your lines as nice as possible, and, to my own idea, the less hollow a line the better it is. Then again, as I said before, some like the midship section for- ward of the half-length of the boat, while others, myself included, prefer it abaft.

It appears to me that, considering a vessel is nothing more or less than a wedge driven through the water, the smaller angle that wedge has the easier it will separate the particles of water with a given driving power; and then, again, as water will close up again more easily than it will be separated, so the quicker the lines in the stern con- verge, the better, to a certain extent. In both these, as in every other case, excess is not meant, and you must, therefore, not make too long an “entrance” or too short a “run.”

With regard to the proportion of beam to length, there are one or two points to be considered before deciding this matter. Firstly, beam gives a vessel greater carrying power, and, to a certain extent, greater “stability” (by stability is meant the power a vessel has of resisting any force which tends to press it over on its side, when in the water, of course) —or, I should rather say, greater “stiffness.” A broad and shallow vessel is “stiffer” up to a certain angle of inclination than a narrow and deep boat, but press both over to that angle and you will find that past that point the broad vessel will perhaps capsize easily, whereas it will be impossible to capsize the narrow but deep one, since she will always right herself again. Now this is easily explained when you know that there are two very important points, or “centres,” in a ship: the one known as the “centre of displacement,” which is in reality the centre of gravity of the mass of water which the ship “dis- places,” or takes the place of, when she is put into the water i and the other the “centre of gravity” of the ship itself. When a ship heels over you can readily see that her centre of displacement will shift, because the shape of the water she displaces alters as her own shape differs under water, according to the various angles of inclination. Therefore in a shallow ship, where the centres of gravity and displacement are close together, the centre of displacement has to shift very little to cause the vessel to capsize; but in a deep boat it has to shift a great deal, since the two centres are further apart. So, then, in a model you must com- bine the qualities of a broad vessel and a deep one; but take care not to get her too broad, because the lines will not be fine enough in that case, nor must she be too deep, since the more surface a boat has in the water the greater is the resistance caused by the friction of the water on her sides to her headway.

I am afraid space will not permit me to say more about designing, but practice will assist you more than anything else, and if you can reason a few points out for yourself, so much the better. About the centres I shall have more to say further on, when we come to building.