Prospero

Prospero

by W.J. Daniels (1912)

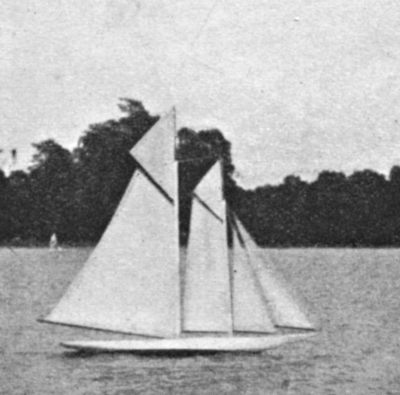

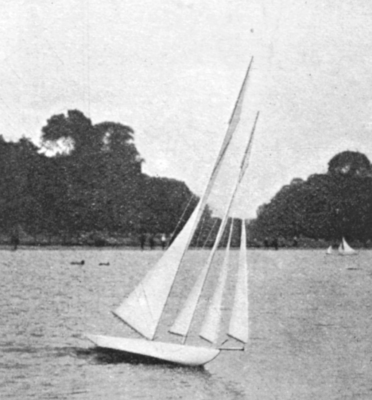

It has for years been generally accepted as law that the schooner rig is not so effective for windward work as that of the cutter, but many old theories have been proved false in model yachting of late, and the schooner Prospero—the design of which is published in this issue—proves conclusively that it is possible to design and build a schooner-rigged model that will hold her own with the very best of the cutter fleet.

It has for years been generally accepted as law that the schooner rig is not so effective for windward work as that of the cutter, but many old theories have been proved false in model yachting of late, and the schooner Prospero—the design of which is published in this issue—proves conclusively that it is possible to design and build a schooner-rigged model that will hold her own with the very best of the cutter fleet.

On her very first weather board over a course of 280 yards she gave the 10-Rater Valiant 30 yards start and overhauled and passed her to weather in as true a sailing test as one could wish for. Those who saw Valiant win the Cleveden Cup will realise that she is no mean trial horse. Of course, some allowance must be made for the difference in rating of these two boats, but the margin of superiority was more than the handicap demanded by Y.R.A. (The Yacht Racing Association, which governed full-sized yacht racing, handicapped schooners owing to the rig’s ability to carry sail—Ed.) rules. Anyway, the schooner proved her ability to point as high as the sloop without loss of speed.

From a model sailing point of view, the schooner rig presents many advantages over the cutter. Firstly, nearly half of the total sail area is forward of the C.L.R. and either the jib, staysail, or foresail may be used to steer with. By this, I do not mean that you should flatten any of them for the purpose of making the model find her heads (as if a boat is properly designed all the sails should have the same mean angle), but that a slight adjustment of any one of them would be more gradual in its effect than if the whole were in one sail.

The great trouble in a model schooner is to keep the gaff of the foresail aboard. This sail being high and narrow has a tendency to swing off unless very little sheet is given, in which case it jams on the horse, and more often than not stops on the weather side when the boat is put about. It is totally wrong in principle to sheet any sail from amidships. The manner in which this trouble was avoided was by means of a stay lead from a point 1 1/2 in below the gooseneck to the middle of foresail boom, and adjustable with a bowser. This, while serving its purpose, does not prevent the sail swinging (Essentially a vang, which were quite rare at this time—Ed.).

The great trouble in a model schooner is to keep the gaff of the foresail aboard. This sail being high and narrow has a tendency to swing off unless very little sheet is given, in which case it jams on the horse, and more often than not stops on the weather side when the boat is put about. It is totally wrong in principle to sheet any sail from amidships. The manner in which this trouble was avoided was by means of a stay lead from a point 1 1/2 in below the gooseneck to the middle of foresail boom, and adjustable with a bowser. This, while serving its purpose, does not prevent the sail swinging (Essentially a vang, which were quite rare at this time—Ed.).

Before dealing with this boat as a schooner, I would like to point out the various vices that it is possible for a yacht to possess which detract from her straight sailing, and to analyze the particular effect that each of these vices have upon the performance irrespective of any particular form of rig, which vices, being in the hull, cannot possibly be eliminated by alteration either of proportion of headsail to mainsail, or the position of the whole over the hull.

If a yacht’s hull is possessed of a feature which gives (in spite of her being bilateral when upright) a natural weather helm when heeled, and in motion, the shifting back of the sails will not cure it. You may overpower this force by so doing, but in all probability the rig will be so far back that as soon as she meets a lighter wind and becomes more or less upright and slowed down, this natural weather helm has disappeared, and the model will go into irons, the rig being too far aft for her to pay off, and being unable to again develop that weather helm that she obtained from the motion given her at the start of the board, she will remain in irons.

Therefore, if we can eliminate those features that tend to steer the boat towards the direction in which she is heeled we shall have solved the problem of running off the wind. For my arguments to be consistent, to overdo the cure of these features will be to create the very opposite effect—that is, a tendency to sail away from the direction in which the yacht is heeled. Experiments carried out by pushing models possessed of this vice when artificially heeled to varying angles in smooth water and minus their rigs have proved these contentions true.

It will be seen why a model that holds good wind in light airs may run off as soon as the speed increases, and why another that cannot look at the wind when it is light will go well under it in a stiff breeze.

Should the after-body be harder to drag than the forebody is to drive, the resolved centre of resistance to forward motion will travel slowly aft. This is proved by the fact that in the case of a large yacht that carries her helm dead amidships when going to windward, she requires lee helm to stop her running off when towing another boat. Another feature that will have the same effect is when the fin, or in other words, the centre of area of the underwater vertical plane, is too far back. This was the case in the Boston America Cup defender Independence, and also Constitution. In light winds these boats could point just as high as the Columbia, but as soon as the wind increased and caused the yachts to heel over they demanded lee helm to keep them pointing, consequently sliding bodily away to leeward. There is yet another feature that has become very prominent, especially in metre models, which perhaps, is more serious still in producing the effect of broad-reaching when close-hauled; and this is converging stream lines in the after garboard—a matter that would take too much space to deal with fully in this volume. It is sufficient to say here that this is a question dealing with the proportion of the fin or keel that should be included in the calculation of the displacement curve.

The very first essential in a yacht’s design is that her fore and aft proportions shall be so arranged that at each and every angle of heel, the imaginary line joining the water line ends amidships remains parallel to the surface of water—that is, assuming the latter to be more or less smooth.

Should, on heeling, the boat stoop by ,the head (known as boring), the leading edge of the fin or centreplate will at once try to cut its way downwards. ‘The buoyancy of the yacht resisting this, we have an inclined surface being dragged through the water in a direction other than parallel to its natural axis, producing a great resistance to forward motion, and dragging the resolved centre of resistance forward. All yachts that bore, tend to gripe up into the wind as their speed increases. In the same manner if a yacht squats by the stern when heeled, the after-body becomes a drag upon the whole; and she will run off the wind, because the resolved centre of the resistance to forward motion of the new shape that is immersed is then further aft in relation to the C.E. of sails than when upright. It will thus be seen that it would be more detrimental to a yacht’s performance if her entrance and delivery were out of harmony with each other, than if the fore-body or after-body were reduced to correspond to the speed of the slower.

As it is seen that certain features create different effects, it is quite possible to use one of these features to counteract another of opposite effect. Many inferior hulls have been made to sail straight by this means, but these vices are fighting against each other, and, of course, produce a great loss of speed, leeway resulting.

Another serious feature is when the axis of the new shape that is immersed when heeled becomes out of parallel with the original amidships line. You then have your hull wanting to point either a closer wind than the fin, if the fore-body is too fine, or vice versa if the opposite is the case.

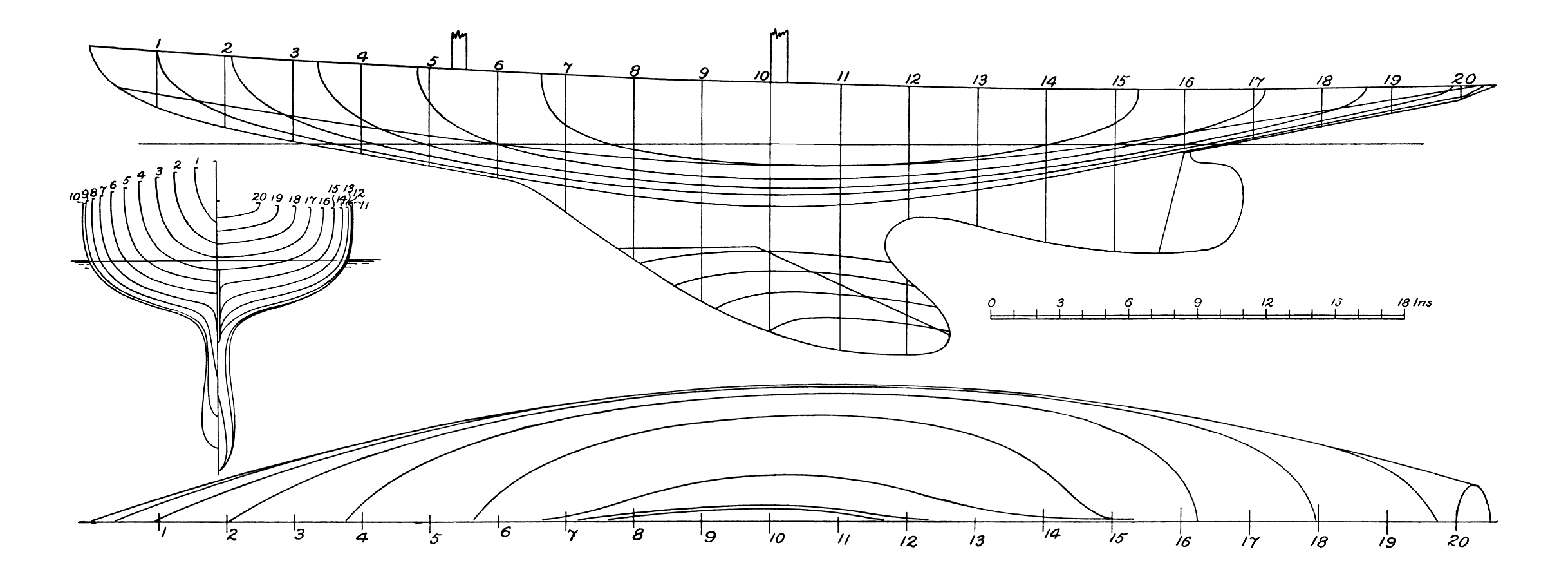

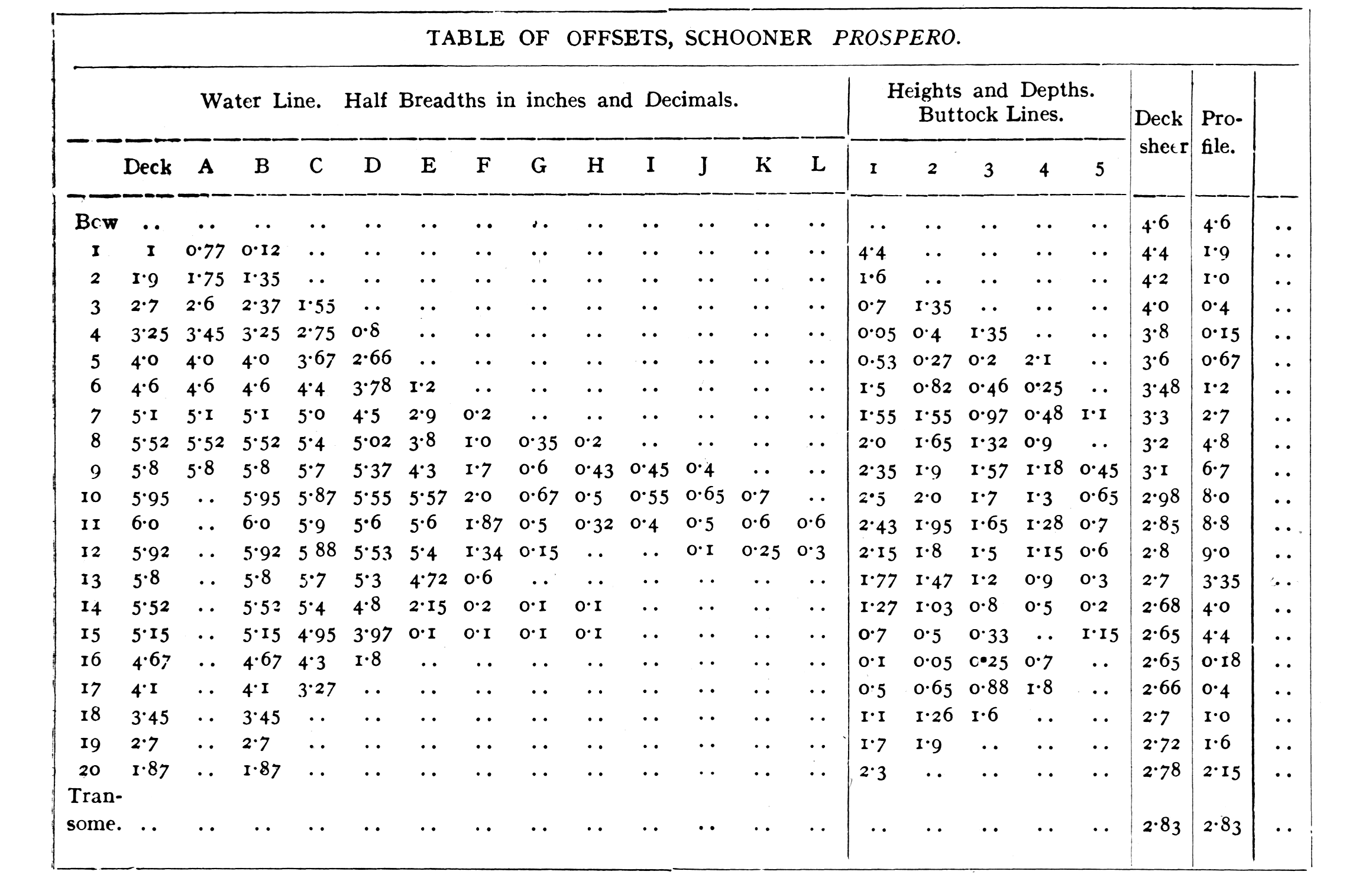

Table of offsets available as a PDF.

It may be asked how it is to be arranged so that the centre of forward resistance of the hull will remain in a fixed position. As a matter of fact, it is not desirable that it should remain exactly so, but should move forward and keep a position of relative to the centre of effort of the sails, which, as has long been proved, moves forward in proportion to the speed at which the wind passes across them. As by heeling the boat increases her length more aft than forward, this feature is taken advantage of, and by placing the largest immersed section slightly behind the middle of the L.W.L. it is arranged that it becomes exactly amidships when heeled to the maximum sailing angle, and thus causes the displacement curve which, when upright, was slightly shorter abaft the greatest section, to become of equal length either side of its highest point, and if the sections are in character throughout the hull it will maintain same graduation. In order that the the yacht shall use her overhangs it is necessary that they shall be of correct proportionate buoyancy to that part of the hull which will be immersed when heeled. Overhangs that are simply licked by the bow and stern waves are more detrimental than useful. In order to remove the reserve buoyancy amidships as much as possible, and to increase the call upon the overhangs, some designers tumble home the topsides, but the very slight decrease of sectional area is so small that it is not worth much, as not only does it flatten the stream-lines and topside diagonals, but it makes the boat lifeless when before the wind.

As all these features have to be taken into consideration irrespective of rig, and are concerned in the hull alone, the proportion of driving sail to pulling sail should not have any influence on hull design, providing the latter is free from any of the before-mentioned vices, which tend to steer her. In other words, if the hull of its own accord does not develop a tendency to sail in a circle when pushed in smooth water artificially heeled without her sails on, it is a simple matter to get a suitable sail plan and its correct position of C.E. over the hull. A sail plan, in which the mainsail forms a large proportion of the whole, will demand the centre of effort further forward of the C.L.R. than if the proportions were more equal. As the ability to point high in light winds practically depends upon closeness of the C.E. the to the C.L.R., it is only necessary to design a boat that will carry a large proportion of headsail to windward in a strong wind, to ensure her holding a good wind when it falls light. It is a fallacy to believe that a yacht will not go to windward under headsail alone, in proof .of which it may be stated that a race sailed by the South Coast One Design Class, in which three out of five starters carried staysail alone, the other two having reefed mainsails, the latter two finished behind the other three, and, curiously enough, it was on the windward legs that the former made their gain.

As it will be seen from the foregoing statements that in order to carry a large proportion of headsail to windward it is absolutely necessary that every vice tending to give the hull artificial weather helm must be eliminated, it is patent that in a hull that is to be a schooner (which of all rigs has the largest proportion of headsail) these vices would be fatal.

As it will be seen from the foregoing statements that in order to carry a large proportion of headsail to windward it is absolutely necessary that every vice tending to give the hull artificial weather helm must be eliminated, it is patent that in a hull that is to be a schooner (which of all rigs has the largest proportion of headsail) these vices would be fatal.

It was, therefore, with great interest that the writer received a commission to design and build a schooner which would give him a chance to prove whether the theories which he as found pay so well in the 10-Rater and 12-meter classes would hold good under this rig.

This boat is not as extreme as are the 10-Raters Onward, Valiant, or Carina, but we should not have any hesitation in adopting quite as extreme features in future.

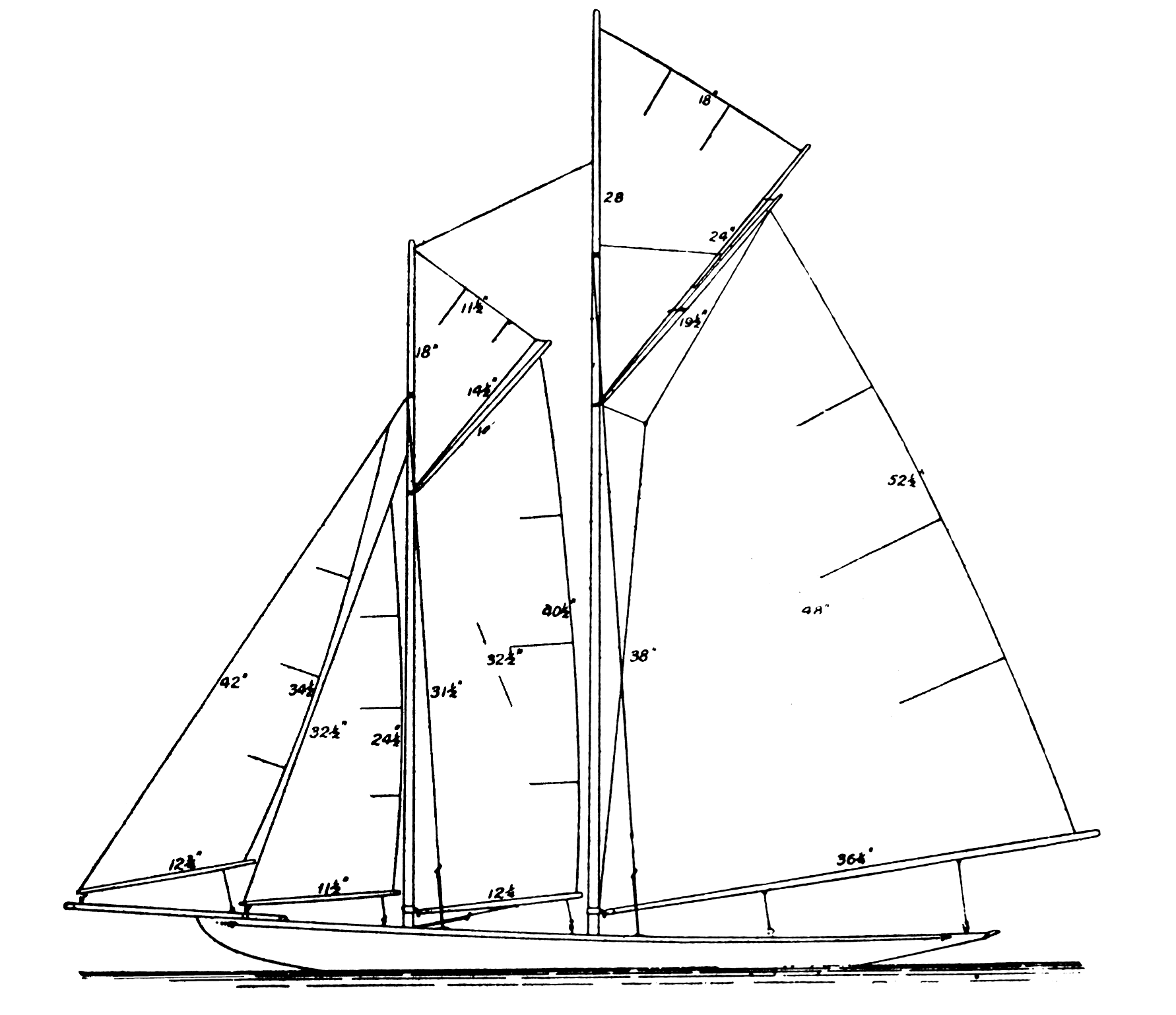

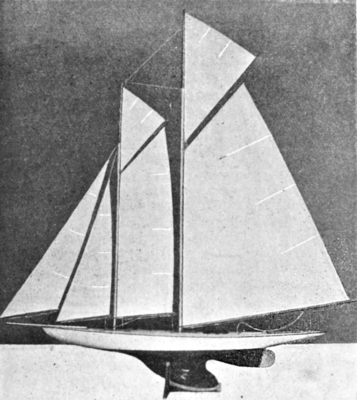

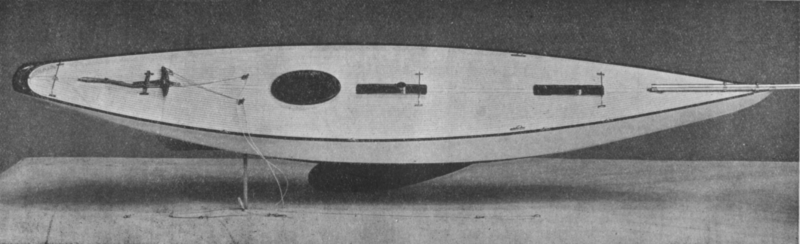

The hull of this model is built of pine, is finished in white topsides and malachite under-body, and all the fittings are of brass, nickel-plated. All the spars are of pine, except the masts and bowsprit, which are 26-gauge aluminum tube. The hull is 61 1/2 in over all, 41 in on the load water line. It will be noticed that the actual L.W.L. comes between those shown in the design. This was done for economy and for no other reason. She has sails of the finest union silk, and is fitted with the steering gear invented by Mr. G. Braine, of the Model Yacht Sailing Association, which piece of mechanism is, perhaps, the greatest of all model yachting inventions.It is used universally in the Metropolitan area, and even in Guernsey the writer found it fitted to his opponent’s boat on his recent visit there for the Channel Isles Championship, much to his surprise and very nearly to his cost.

Prospero‘s total displacement is 20 lbs., and she has 12.5 lbs. of lead in her keel, which latter is brass shod, and is bolted right through the fin with 10-gauge motorcycle spokes. The details of fittings are apparent from the drawings and photographs, and nothing that could be done to ensure success was neglected. It is remarkable with what quickness she alls again after coming about on the gye, but this is due to the large amount of headsail that spills when she comes into the wind, and the great distance the C.E. of the mainsail is behind the C.L.R. The writer may say, in conclusion, that the advent of this model should promote a schooner class, and create fresh interest in model sailing; and that her successful performance has given as much satisfaction and pleasure as did the champagne lunch that her owner stood in honour of her launch.