- MOBY DICK A fascinating, really heavyweight ‘A’ Class design by John Lewis

- TWIN-PAK an ultra simple sailing catamaran model ideal for younger readers or as a school project By P. Darbyshire

- Notes for the Novice Model Yachtsman This month A. Wilcock discusses sail balance and mast position, helm requirements, and the background leading up to vane steering gears

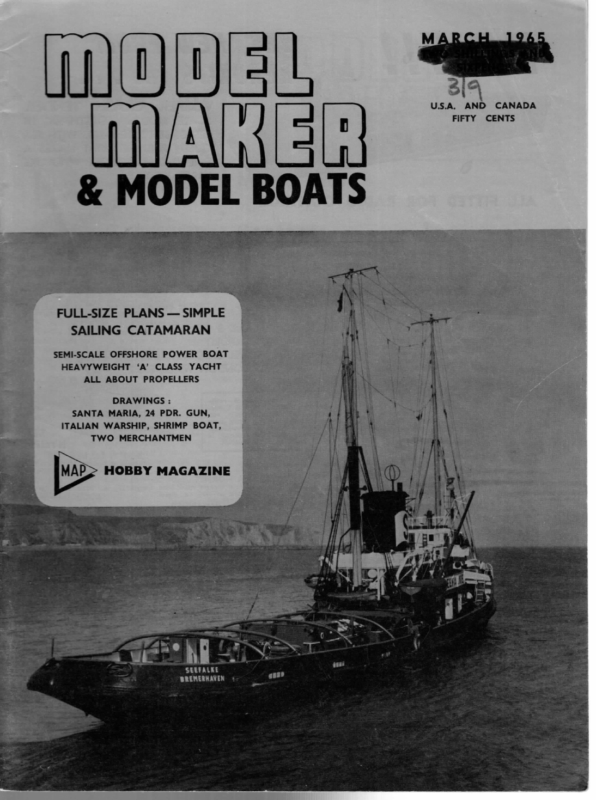

r [a\ & MODEL BOATS FULL-SIZE PLANS — SIMPLE SAILING CATAMARAN SEMI-SCALE OFFSHORE POWER BOAT) HEAVYWEIGHT ‘A’ CLASS YACHT ALL ABOUT PROPELLERS DRAWINGS : SANTA MARIA, 24 PDR. GUN, ITALIAN WARSHIP, SHRIMP BOAT, TWO MERCHANTMEN HOBBY MAGAZINE SEEFALKE. BREMERHAVEN i FIFTY CENTS U.S.A. AND CANADA

MOBY DICK A fascinating, really heavyweight ‘A’ Class design by John Lewis Fo some years now I have been toying with the idea of designing a very large and heavy A class model and recently have spent a lot of time reviewing previous designs. It would seem that the time is ripe for such an experiment in this country. It has already been done with some success in America, particularly on their West Coast. There are several approaches to the A class prob- lem and a choice has to be made before putting pencil to paper. The rule is so framed that whatever choice of principal dimensions is made the yacht will stand a good chance in competition, providing all normal conditions of naval architecture are observed. I suppose the average modern A boat has settled down around the 54/55 in. LWL and displacements range from 54 lb. to 60 lb. We are in danger of getting stuck in a groove unless some bold people do not strike out and experiment. can be done. So let us see what Years of development in the 10 rater class have shown that narrow beam, a shallow hull and full ends with highish displacement produces the best all round model in compeition. This has been proved by the performance of such models as Sirocco, Whirlwind and Red Herring. The type has to have a full rounded type of midsection rather akin to a very narrow scow. This principle applied to the A class has produced Highlander by Dick Priest and Vital Spark to my own design. Both these boats are 54 in. LWL, 13.6 in. LWL beam and approximately 54 Ib. displacement. That is, they are near the minimum displace- HERTS WATFORD, HO, CLARENDON 16, _ ~~ oF wy DesioneD J. Lewis \ 5 Mi coprmicnt MOBY DICK MODEL MAKER PLANS SERVICE ment allowed by the rule without taking a penalty. I have tried to develop these designs further and it would seem that they are very near the point of maximum development. In order to get more inherent speed the first thing to do is to increase LWL, but this forces the displacement up beyond the figure obtained by mere linear increase. Either we have to increase beam or hull depth, and in doing so we destroy the effectiveness of the type so painstakingly developed over the years. An increase in beam will slow the boat down under all conditions and an increase in depth will spoil the running characteristics. More displacement can be got by thickening the keel Yachting readers have asked us to print dimensions, etc., separately where the reproduction of the drawing is small, For “Moby Dick” they are: L.O.A. 90.6 in., L.W.L. 60 in., beam 15.5 in,, draught 13.1 in., Q.B.L. 65.1 in., cube D 12.6 in., S.A. 1,449 sq. in, displacement 76.1 Ib., lead 58.1 Ib., trimming ballast 2 Ib., average freeboard 4.6 in., sections spaced 6 in., waterlines spaced -75 in. Please note plan is half-size as purchased. 102

MARCH but I have already found that there are distinct limits to that approach. If there is a weakness in this type of A boat it is that the light weather performance is suspect and nothing must be done which will add to this defect. It is mainly a matter of reducing wetted surface areas without being forced into increasing beam or hull depth. Very regretfully I have decided to abandon this type for the time being and to pursue a different line, as I do not see any answer to the difficulty at this moment. However, st a in hope because it is my favourite type of ull, Now if we consider the heavier models designed by Turner & Daniels we can see the greater hull depth, the greater beam on LWL, and with a much easier type of midship section a reduced wetted surface is achieved. Freeing ourselves from the narrow scow concept we are able to play more easily with all the dimensions and only lose on one account. That is, the ability to plane fast and early as will the narrow scow. We gain on being able to carry a heavy displacement on a given LWL which nearly always improves windward performance in a model and we can have a hull with low drag for light weather performance. It is a well known fact that the heavy boats do well in light winds on all points of sailing. The higher displacement is treated kindly by the rule and enables us to recover some lost sail area forfeited by increasing LWL. My designs Moonshine and Top Hat are moderate examples of the type, that is dimensionally, for in performance they are very good indeed. It has only been on very rare occasions that Highlander has beaten Moonshine to windward and only in marginal planing conditions is Moonshine slower down wind. Moonshine is 55 in. LWL, 60 1b. displacement and 14.2 in. LWL beam. As Top Hat is a development in detail of Moon- shine. I thought the time had come_for a bolder change in basic dimensions. Firstly, how much longer can we go on the LWL? We know of several successful A boats sailing on 56 in. LWL by accident, so that has already been done. What about 57 in., 58 in., 59 or 60 in.? I decided to jump straight up to 60 in. LWL in Moby Dick on the principle that a decisive change is more instructive than a marginal increase and that I had news of the Americans teetering between 58 and 60 LWL. There is also a 61 in. LWL design in existence in the U.S.A. After several tentative drawings I was delighted to find that I could absorb about 75 Ib. displacement on 60 in. LWL without a disproportionate increase in any other vital dimension when compared with the Moonshine type. For example, although Moby Dick is 153 in. LWL beam this is no greater in fact than a number of successful boats of 55 in. LWL and gives the almost exact beam/length ratio as Moon- shine. The hull depth of 6 in. is not greater than OTHER ‘A’ CLASS PLANS IN OUR RANGE ARE: Design Highlander Saxon Windflower Cirrus Bolero Moonshine Top Hat Vital Spark Nova Plan No. MM/482 MM/452 MM /320 MM /464 MM/559 MM_/606 MM_/670 MM //684 MM /783 Designer _Priest Priest Tucker Witty Andrews Lewis Lewis Lewis Witty 1965 many existing designs and on 60 ins -LWL will not make the new boat any tubbier in this respect. Her run aft will be as low and clean as any. The surface area of the hull is smaller than many existing designs and this fits in with the inevitably reduced sail area. Nevertheless, careful shaping of the profile has enabled the whole keel to be a lead casting without any deadwood. Neither is the keel too thick for good windward performance. A heavy boat is able to use long overhangs and it will-be-seen that-both fore and aft profiles of the hull have distinct kinks in them so that the length can be drawn out. Everything about Moby Dick has been very care- fully considered and I am delighted with the way the hull lines developed. It. would be possible to reduce the LWL beam to 15.0 in. and drop the displacement to 71 lb., which is near the minimum allowed by the rule, but sail area would be lost. However, it is a possible line for further development. Moby Dick is allowed 1,449 sq. in. of sail by the rule and I know a lot of people will think this is too small. In fact if I were designing the most efficient sail plan possible with present knowledge and to the height limitation imposed by the rule this area would be almost exactly the result. In other words an aspect ratio of just over 3 to 1 in the fore triangle and just under 4 to 1 for the mainsail. We also know that some big American boats are doing well in light airs with only 1,393 sq. in., so some extra comfort can be drawn from that. One thing is certain; Moby Dick must have a good selection of spinnakers. It is no good just hanging up any old bag and a lot of time should be spent in learning how to trim a spinnaker under all conditions. The biggest sail does not necessarily produce the most drive in light winds and a flattish cross-cut spinnaker is required. Again, a flat spinnaker is best with quartering winds and only when there are medium to strong winds should the large full cut sail be used. It will be noticed on the plans that I have allowed for 2 lb. trimming ballast and this has been done for two reasons. Firstly a large hull of this sort can vary by at least 2 Ib. from builder to builder, and secondly I think the lead casting will have at least this variation depending on the care taken by the foundry. With at least 58 Ib. in the keel a spare 2 lb. in the hull to get the trim correct will not impair the performance. On no account though let the total weight exceed 76.1 1b. Moby Dick will be a ‘disc-slipper’ and she should not be handled by one man. Builders will no doubt give careful consideration to lifting and it might be worthwhile having a handle bow and stern in the form of a ‘pulpit’ and ‘pushpit’ as seen on modern ocean racers. Certainly a pulpit on the bow would also make stopping downwind somewhat easier. L.O.A. in. 719 81 “78.4 78 39.5 84 81.25 79.5 79.8 L.W.L. in, 54 55 56 54 54.2 55 55 54 54 Beam in, 13.75 14.6 14.3 14 1:2 14.3 14.25 13.6 14 Model Maker Plans Service, 38 Clarendon Road, Watford, Herts. 103 LLL | Price Displacement £ os. d. Ib. : Pakage HESol 52 Pama 56.5 15. 0 31.25 12 6: 53 PAM ei 55) 10 39.5 15-0 60. 15.0 a) keg 10 6. o 52,9 :

”i “EB TWIN-PAK an ultra catamaran younger simple model readers school By Bot P. sailing ideal or for as a project Darbyshire mainly from scraps of hardboard and orange-box wood and covered with gummedstrip paper, this miniature catamaran will sail well and should cost very little over 2/6d. to construct. All stripwood mentioned is of the obeche variety obtainable from most model shops. The Hulls As the craft has no. sheer, it was found simplest to start with the decks. The bridge-deck is assembled from three pieces of stripwood 1 in. x 4 in. A centre- piece 53 in. long, which carries mast and keel is glued under two 63 in. cross-members at right-angles with a gap of 33 in. between the cross-members. Next cut out the decks from hardboard with a fretsaw to the shape shown on the plan. These are glued, smooth side uppermost, across the tops of the cross- members with 3% in. projecting forward from the leading edge of the forward cross-member. There should be a gap of 2% in. between decks at their beamiest points. Alignment is very important here and a good idea is to rule a centre line down each deck fore and aft. These lines should be parallel to one another and at right-angles to the cross-members. In the prototype Evo-Stik was used for most joints except the smaller struts which were glued with Durofix. Bulkheads, triangular in section, are now glued to the underside of the decks in the positions shown in the plan. These bulkheads are fretted out of orangebox wood (approx. 3 in. thick). Care should be taken that the grain runs from base to apex of these. The forward bulkheads are glued hard against the stem pieces. The two keels are added next. These are lengths of 2 in. x & in. stripwood glued from bow to stern along the flattened apexes of the bulkheads. A 42 in. length of 4 in. x % in. stripwood is glued across under the decks at the extreme bows. Next, small lengths of % in. x % in. stripwood are glued between the bulkheads, round the outer edges of the decks. Light intermediate struts are now glued with Durofix between all the bulkheads at about 3 in. intervals from bow to stern. They are cut to fit individually with a modelling knife and are best added in pairs port and starboard for uniformity. Their ends should be chamfered to fit snugly against the keels and the under-deck bulkhead-spacers. The hulls are now ready for skinning. Covering the Hulls Both hulls are now skinned carefully with brown gummed-strip paper. For best results do not attempt to use strips wider than 1 in. On the prototype the paper was stuck direct to the raw wood and hardboard but to ensure easy adhesion it might be an advantage to varnish the framework first. Apply the first layer from stem to stern starting at the stern end of the decks. Having stuck one length, work downwards towards the keels overlapping each strip slightly. This job should not be hurried and the gummed-strip should be constantly smoothed down to ensure a good surface. Great care should also be taken in covering the areas where the cross-members enter under the decks. Having covered both hulls completely with lengthwise-running gummed-strip, add at least two more layers running diagonally from deck to keel, remembering always to work from the stern. A_ small wooden block 1 in. x $ in. x 2 in. with a 3 in. hole drilled through its centre and raking aft slightly,

MARCH 1965 truding above the blade which is streamlined like the keel. Mount the rudder by screwing in two screweyes corresponding to those on the keel and slipping a doubled length of brass wire through all four, turning the ends of the wire over with pliers. Two more 4 in. lengths of 4 in. x & in. stripwood are glued together lengthways to form a ‘T’ girder and this is glued centrally into the slot above the blade. Painting The prototype was given a coat of marine glue over the gummed-strip paper. Then the entire hull, keel and rudder were given three coats of white undercoat, sanding lightly between each, followed by a coat of Humbrol enamel. Decks were lined in pencil after the undercoats and finally the whole hull assembly was given a coat of polyurethane yacht varnish. Rigging The mast is a 15 in. length of 3 in. beech dowelling tapered at the top with small holes drilled through it as shown on the plan. The boom is an 8 in. length of 4 in. dowelling also drilled as on the plan. Mast and boom can be either varnished or painted with silver paint to simulate alloy spars. The gooseneck is made from two interlocking brass screw-eyes. [Continued on page 129] This is a ird full size drawing of the sails required for TwinPak. Main-boom, jib foot, and mast heel will be found drawn in full with the full size construction drawing overleaf. completes the hull construction. This hole is then continued through the cross-member and centre-piece. The Keel This is fretted from hardboard to the shape shown on the plan. The top is glued into. a groove in a 2% in. length of 4 in. x 4 in. wood (cedar is excellent for the purpose but any knot-free softwood will do). Cut a piece of lead 1% in. x 13 in. by about .01 in. thick and bend it in the middle; smear the inside of the lead and the bottom of the keel with Araldite and clamp in position in a vice. This will have to be left for about three days, so meanwhile the mast and sails could be made. When the lead is stuck, glue and screw (brass screws please) the keel assembly under the centrepiece between the hulls. Make sure that the rear of the keel is exactly flush with the trailing edge of the after cross-member. The _ keel should be pared to a good stream- line section with modelling knife. Three lengths of 4 in. x 4 in. stripwood are glued to the upper trailing edge of the keel, one slightly shorter being glued to the edge of the hardboard and the others sandwiching it and the edge of the keel also. These are to hold the two screw-eyes for the rudder-hinge. The Rudder Cut from hardboard and sandwich between two lengths of 2 in. x % in. stripwood with 3 in. pro-

alk a Tees LOOSE=FOOTED JIB ——}-+% t ~. a Eee BRIDGE DECK FROM STRIPS OF I” x §” HA 3″ x “STRUTS | | SIDE ELEVATION ~~ es BULKHEADS I=-3 AND TRANSOM FROM 41″ ORANGE BOX WOOD GRAIN DIRECTION | TRANSOM amT \\ y \{ I” x 3″ x 3″ HARDWOOD CENTRE LINES OF MAST BLOCK SPACED AT 44″ 7; /, OPENED SCREW-EYE Z| |_ = = / ee -|+— SCREW=EYES be hid ee DECK PLAN – DECK FROM HARDBOARD KEELS ARE FROM 4″ x 3″ HARD WOOD STRIPS

SAIL BATTENS FROM I mem. PLY cate — | | ] HREE bri »WOOD ai ae Sibi = a I ; [ 4 , J i ?— | ie Such wel ee 3 | thee | || il | nee “4 4 —— TFT — a 4 SCREW-EYES ULLS FRET KEEL FROM HARDBOARD 1 eee (2 eee 5″ x 14″ x 5 LEAD BLOCK ee| > | Ae ee | GN escheat re seg | ‘is Be ow tig Al poe ee ne ars ene eS | og | fe a a | | | HINGE FORM RUDDER ri WIRE PIN M FRO ER RUDD BRASS WITH GASB BOARD ES es ; | eS ere | | SCREW EYE- | | BOTH HULLS —

to leeward, i.e., to the side of the boat that the booms are. This is called weather helm, since if there were a tiller projecting forward of the rudder post as on a manned craft it would be pulled over to the weather side of the boat to give this movement to the rudder blade. The angle of movement needed = == \ is only small, and increases slightly as you move towards a full run. The carrying of a spinnaker reduces or eliminates the need to carry helm because it corrects the unbalance of the sail plan. It is seen then that the spinnaker has two very beneficial effects. (1) It reduces or eliminates the drag caused by helm. (2) It adds more driving force in the nature weieur —— FF| J = = se == 5 Fike) = THREADED ROD TO ADJUST POSITION OF WEIGHT UR attention can now be directed to helm or rudder requirements in a theoretical way; the practical aspects will be covered in the sections on steering gears. Good model yachts have been renowned for their balance. This is a complicated subject and one beyond the intention of these articles so we must be satisfied with a thumb nail definition. It is the design property by which as the heel of the boat varies in varying wind strengths as it is sailing it maintains its trim and holds to the same course. Assuming we have a well designed balanced hull it is necessary to have the sail plan—that is the jib and mainsail attached, as described before, to the mast—correctly situated over the hull. This is usually achieved by being able to move the mast slightly in a fore and aft direction while mainta’ning its rake. Then with the sails set for a close beat (see chart) the boat will sail a steady course at about 30 deg. to the wind. This should be tried with the rudder held firmly central. If the mast is in the correct position it will do so. If it sails up into the wind, sails-flapping, the mast is too far back, while if it bears away as if on a free beat or even a close Notes for the Novice Model Yachtsman of square inches of sail. The use of a rudder to turn corners as in a full sized craft does not normally arise in models, although it will be seen later that it can be used for guying and jibing. This simple explanation of the need and use of the rudder with model yachts will suffice for the moment. Having described the ‘engine’ of our model yacht (the sails) and its relation to the body (the hull) at some length, we can now turn our attention to steering it. It may be of some advantage here to record, or re-record, some history. Model yachting has been an organised hobby, sport and recreation for over a hundred years. A few reach, then the mast, i.e., sail plan, is too far forward. In either case the mast should be moved to correct it. Having found this position it will be found that the courses from a close beat round to almost a full reach can be sailed by purely setting the sails according to the chart. These are the courses on which years the whole of the jib sail and the whole of the mainsail can ‘see’ or feel the wind unimpeded. As soon as the wind is striking the sail plan from abaft the beam then the mainsail ‘shades’ the jib to a lesser or greater extent and the driving force on the sails is no longer balanced. The pressure on the jib is lowered and the unbalance tends to move the bow of the boat round to head into the wind; it is from this point that helm is needed to counteract the unbalance and to do so the rudder blade needs to go ago one of the London clubs celebrated its centenary and others in the area are over 75 years old. The boats themselves have evolved almost out of recognition in this time, as well as the method of steering them, as we shall see. Before 1900 it would appear that two basic types of steering were in common use apart from the semi-fixed rudder which is unfortunately still seen on some shop models and can only lead to frustra- tion and disappointment to their purchaser. These were the weighted rudder and reversed tiller. A weighted rudder is illustrated in Fig. 6. Old books and articles show refinements to vary the position of the weight and therefore its effectiveness.. From what was said in the last section on the need for a central rudder it will be appreciated that a balanced boat heels most on those courses (beating and reaching) when helm is least needed or not at all. By current experience and theory a weighted rudder is therefore almost useless. No doubt at the time the sail plans of the craft were set sufficiently far back to cause the boat to head to the wind and the rudder would correct this. The successful model yachtsman was the one who could best get equilibrium and balance of the forces. Having written that, one realises how true it is even today, but in a quite different set of conditions. Unfortunately one still sees weighted rudders on quite expensive commercial products, while devices which are much more 116

1965 MARCH effective could be QUADRANT incorporated at relatively little extra cost. The reversed tiller illustrated in Fig. 7 as the other type of steering of the time did offer more sensible control and as a really simple device for the novice, without aspirations to funny tricks, will still permit course sailing, i.e., the boat going where you want it to, as distinct from going where it wants to. With this plan, the mast position should be placed to give good beating courses without helm and with the beating sheet connected to a horse. When the de- sired course is a reach or run the beating sheet is detached from the horse and hooked up on the This month A. Wilcock discusses sail balance and mast position, helm requirements, and the background leading up to vane steering gears boom and the running sheet connected to the reversed tiller comes into play. Its effectiveness is determined by the point of connection to the tiller and the strength of the centring line. Note how the centring line is not pulling on the rudder post which could cause binding, but its action is obtained by passing it through a hole or eye. This feature will be found to be used whenever a strong pull could be exerted by the centring line. In about 1904 Mr. G. Braine invented the Braine steering gear which held sway in this country till after the second world war and is still found in diminishing numbers in organised racing. It is interesting to record that the parts of the original gear are still displayed on a board in the clubhouse of the Model Yacht Sailing Association, Kensington Palace Gardens. Fig. 8 shows the final development of the Braine gear with main and jib lines and separate port and starboard stops and tension adjusters. Its enormous advantage over its predecessor was that its action on port and starboard tacks could be controlled separately and precisely. For best performance a balanced hull with the sail plan set over the hull for good beating without helm was called for. For beating courses the main and jib sheets were hooked to horses and for reaching and running, to the lines connected to the quadrant. Only top class racing boats worried about the jib lines to the quadrant but in the hands of the expert they would play a valuable part We can now turn to vane steering gears. In spite of what has already been said, it is recorded that the idea of vane steering was first put forward by Nathaniel Herreshoff in the late 1800s in one form, from a burgee flying at the mast head, and secondly in the currently more conventional position near the rudder post. Somehow it never ‘caught on’ and it was not until Iverson and Berge experimented. in the early 1930s, with a non-self-tacking vane on the lines suggested nearly 40 vears before, that any practical interest was shown. From what is now known about vane steering one can be amazed that 40 years should ADJUSTABLE SIDE STOPS ANCHOR PLATE FOR SHEETS WHEN SEATING VC INDEPENDENT SLIDE 2 tt A. a Cees| SLIDE TO ELASTIC CENTERING LINE ADJUST ELASTIC TENSION elapse between the conception and the first real practical application, and it is worth postulating a reason. Look at any old books and photographs published before 1930 and you soon see that design was still in the era of the gaff rigged sail plan where the jib extended forward of the bows on a bowsprit and the main boom projected well aft over the stern, there just was nowhere to mount a vane and it had to wait till the advent of the Bermudian sloop rig with its tall efficient jib and mainsail which are short on the foot and are now almost universal. The problem of carrying a vane and adequate sail still tends to persist in the 36 in. restricted class. Fig. 9 shows the kind of illustration one sees of the early vane in which the feather holder could be lifted and popped into a selected hole on the scale. The realisation of the need for a counter-balance to the feather came later, as well as the friction movement which gives infinite positioning as distinct from the series of holes. The entry by Sam Berge of Norway of a boat with a vane gear in the International races held in 1935 caused a rage of controversy in the very conservative cloisters of the model yachting fraternity as to whether such a device was within the spirit of the sport or a means of obtaining unmeasured sail area. In this atmosphere little progress was made in this country before the second world war, and it was left to the Americans to develop the device while we were otherwise occupied. Fig. 10* shows a simple non-tacking but balanced gear with friction grip for the feather. This is simple and will give plain course sailing as adequately as the most complicated gear. Its relation to the self-tacking gears we now come to is somewhat parallel to that of the reversed tiller and the fully fledged Braine gear. A world of difference, but the simple gear is within the constructional ability of many a novice and will give good plain sailing, although it is always very gratifying to be able to emulate the manoeuvres of the racing skipper even if you are not racing. It will have been appreciated by now that the next step in development was the self-tacking vane gear, [‘Continued on page 129] — EDITOR. *This illustration will appear next month on THER VANE SLIDES UP POST TO ADJUST ANGLE BY MOVING TO ANOTHER HOLE CENTERING ELASTIC

MARCH selves are cut from 1 mm. ply. TWIN-PAK [Continued from page 109] The bowsies are fretted from derelict rulers, the holes being drilled first. The stays and sheets are made up from lightweight fishing line. The brass screw-eye positions are located on the plan. The mainsheet operates the counter-tiller the other end of which is tensioned from the base of the mast by a rubber band. The sails were cut from old cotton sheet donated by my wife who kindly hemmed them for me and sewed on lengths of 4 in. white tape for batten-pockets on the mainsail. The battens them- SMALL CRAFT [Continued from page 113] The three sail rings on the mainsail are sections cut from toothpaste tube caps with a sharp knife or junior hacksaw. Choose caps of the bendy type plastic which is easier cut without fracturing. A short length of brass wire is twisted into a loop around the bow strut; this anchors the fore-stay. Twinpak sails most successfully and will take much stiffer breezes than a conventional model yacht of similar size She is, incidentally, size for size, appreciably faster. she had left the Medway scene. While fishing from the Medway her number was ‘R.R.4’, I am informed. ing and shrimping in the reduced trade. She remained in the Medway until towards the end of the last war, when she was sold into Thames use as a bawley boat. As a subject for modelling, the Thistle is shown in her auxiliary reduced rig and will make a good intermediary between the fully rigged estuary smack and the modern styled bawleys featured in the November 1964 Model Maker. A fully rigged smack will be featured at some future point to complete the picture. As a model note, the Thistle was reduced in rig in 1944, and the reproduced illustrations show her after NOVICE YACHTSMAN [Continued from page 117] and it is this self-tacking feature which creates the constructional problem rather than utilisation. The self-tacking feature and other refinements are needed to meet two basic requirements: (1) Racing rules on tacking whereby, if the boat is turned by pole from one tack to the other, touching only the hull with the pole, it may be done without stopping; (2) Varying guying conditions (these will be described in the next section), Articles published shortly after the war show clearly three basic types of self-tacking vane gears that had been developed in the States during the war and had got their designers’ names ‘tacked on’, i.e., the Lassel type, Ballantyne type and Fisher type. In YAKIMA VALLEY & BORGSTEN 1965 Her name across her transom was as THISTLE OF ROCHESTER, the boat’s name being on the port quarter, with ROCHESTER being on the starboard. A white trimming flash was also featured on the transom. General Notes and Colours Hull was all black, with a white trim line and registration number. Decks, scrubbed planked wood. Cabin and other wood fittings were brown paint, mast and spar of oiled wood, with the topmast painted buff. Sails, red-brown mainsail, topsail and foresail, with a possible variation of a white foresail. fact it could be said that American designers were keen to publish their ideas and get their name attached as with the Braine gear. These three types are still in very general use and their design points are described below. Before doing so however, mention must be made of a fourth type of self-tacking vane developed in this country in the 1950s and described by the author under the title “A Moving Carriage Vane Gear” in the February 1961 Model Maker and now being used in ever increasing numbers. It is unfortunate that this has not the designer’s name attached as for the earlier types, but this must be put down to the reticence of the British model yachtsman who had a hand in it and so far as the author is aware there was more than one. The basic details of these four types will be discussed in our next instalment. [Continued from page 119] with Seccotine and painted with Humbrol matt paints, was completed in a week of evenings and from the original sheets of veneer (12 in. x 6 in.) and Bristol board, enough material remains for many more models. TAYCOL HIGH POWER — HIGH EFFICIENCY ELECTRIC BOAT MOTORS Powers range from 6 to 64 milli. H.P. Consumption from | to 5% amps. Prices from 28/4d, to 81/10d. plus Tax. Ask your retailer for Price List with complete data for installation of the most suitable motor for your boat. TAYCOL LIMITED MENTION RADIO CONTROLLED VERON “DOUBLE SPECIAL’’, 74 COVENA ROAD, SOUTHBOURNE, BOURNEMOUTH KINDLY A 36” “MODEL MAKER” Taycol WHEN MARLIN — TAYCOL 12 Venner Cells, Taplin 24 x 24 Prop. Motors can be reversed by single pole c/o switch, they have Double Series Wound Fields. REPLYING TO as ADVERTISEMENTS