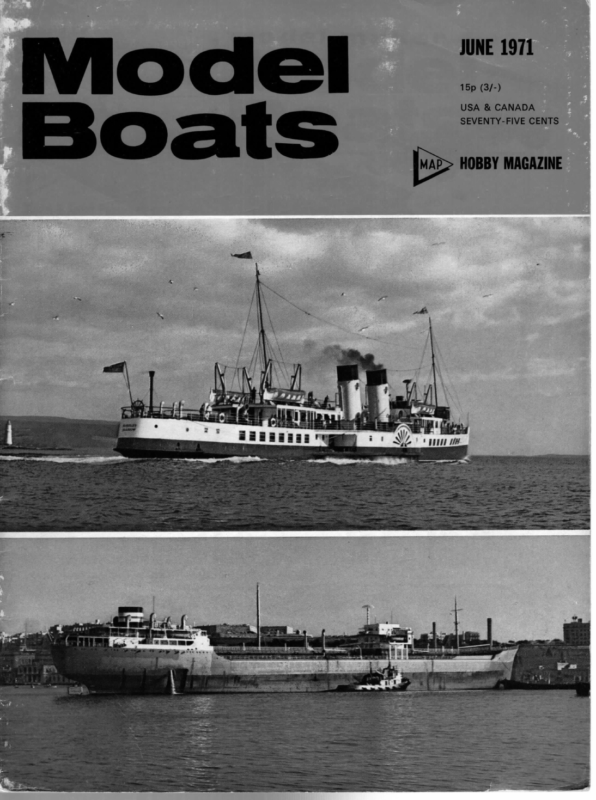

JUNE 1971 15p (3/-) USA & CANADA SEVENTY-FIVE CENTS HOBBY MAGAZINE op ery nell id i fe “un RY ai* eeente on? Ph ee ee ee mc : _ iil A

MODEL BOATS First-ever National Marblehead Team Championships Photographs and notes by Fred Shepherd N April 10th-11th the first National team race for Marbleheads was held at Witton Lake, run by the Birmingham Club. The OOD nominated for the event, Joe Meir, was unable to look after proceedings due to a last minute rather more important engagement. John Allen of the home club stepped in to fill this post. Six clubs entered, which must have been disappointing for the home club, as through the winter months they and members of the Bournville club had put in countless hours clearing the lake of rubbish. Also they tried very hard to lower a sand bar which reduced the depth at this point to about 10 in. This hazard did claim many boats that aimed for the windward shore. After welcoming all competitors Mr Allen explained that two rounds would be sailed. He gave the remainder of his instructions and then racing got under way at 11.20 in a fresh N-NE wind 10-12 mph which gave a beat out from the clubhouse and a rather difficult spinnaker run back. The problem was that if a boat sailed down onto the lee shore one was faced with almost a close reach out to the finish due to the shape of the pondside there. Birkenhead were the only club to score maximum points in heat one and in doing so looked quite a formidable combination, M4SIS sailed by Colin and Walt Jones, and Gay Gordon by Ken and Joyce Roberts. Also looking quite good sailing to windward was Sweet Sixteen from Guildford, sailed by Alex Austin. Racing continued until the lunchbreak at about 1.30 when four heats had been completed. The wind was then lightening a little. Positions were Birkenhead 26, Hove 25, Guildford 21, Birmingham 20. Top to bottom, Roger Cole’s Andromeda, to Fred Shepherd’s Afterthought design. High, powerful bow may have to do with the designer’s suffering downwind with Black Rabbit? Absence of garboard fill-ins is one of the new M class modifications, but what would John Lewis say to that fin? Second, Clive Colsell’s Foxtrot Uncle slips her bow neatly over the top despite tall rig and fair-sized spinnaker, Third, John Beattie brings Sweet Sixteen ashore, one of a number which stuck on a sand-bar in the second day’s light conditions. Bottom, Foxtrot Uncle appears in a good position 20 yards from the line, but M-4-Sis (behind) slipped through to win by a narrow margin on the second meeting between these boats.

1971 JUNE Top, the victorious Birkenhead team, |. to r. Ken and Joyce Roberts, Wally and Colin Jones. Most of them are seen in the second picture hastily altering the very tall rig on M-4-Sis, and Walter and son hold up the cut-off strip with a grin. Their sporting action avoided an embarrassing situa- tion arising from uncertainty of apply. when the new M rules Racing was resumed after a short break and straight away Clive Colsell sailing Foxtrot Uncle, a Slip Up design by Fred Shepherd, beat M4SIS both ways. Hipster, sailed by Desmond Daly from Hove, beat Gay Gordon downwind. It looked then as though Hove were going to call the tune, This effort by the Hove skippers was to be short lived and Birkenhead were soon back in the lead again. By this time nearly everyone was supporting tall rigs with the wind at about 4 mph. With ten heats completed at around 5 p.m. the OOD called a halt. Birkenhead were now in a com- Mien Or ese thd r manding position with 69 points, Hove 58, Guildford 56, and Bournville 55. During the evening the competitors and officials gathered at Mick Harris’ home for a jug and a bite, and to talk over why so and so had beaten them to windward! Sunday 11th At 9.30, with racing to begin in half an hour, the lake was like glass. Everyone was wondering, can it be completed? It was at this stage that doubt seemed to exist as to whether the sailing should be under the previous M class rating rules or those passed at the 1970 A.G.M. Some skippers said they would use their ultra tall rigs which exceeded the 85 in. maximum laid down. The OOD was certainly in a fix; Colin and Walt Jones came to the rescue with a very large pair of scissors and promptly cut a couple of inches off their mainsail, lowered the hoists and chuckled how about that, well within the 85 in. limit! Conditions could only be described as terrible when racing began, the first heat taking something like 14 hours, Luck was now playing a very important part, but fortunately at about 11.45 a wind came in again from the NE and racing became much brisker. At the lunchbreak Bournville were snapping at Birkenhead’s (Continued on page 229) Left, Martini does the painted ship bit and shows the conditions just before racing was due to start on the second day. Beat:No clus GROWING TOTALS Club ] 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 NW 12 13 14 15 te 17 22 26 29 39 44 52 62 69 17 87 87 90 96 Cc. JONES 5 10 12 14 14 19 21 24 29 34 37 42 42 44 47 50 53 58 63 68 K. ROBERTS 3 7 10 12 15 20 23 28 33 35 40 | 45 45 | 47 49 54 59 60 65 70 BIRKENHEAD : 13 | 20 | 23 | 26) 3! 36 | 4 11 13 18 BIRMINGHAM 5 8 C. WEBB 0 0 3 8 8 23 16 7 18 {104 | 112 | 118} 65 | 72 | 77] 47 | 50} 50] 50} 55 | 4I 26 26 26 26 29 32 34 39 39 33 19 20 128 | 138 79 | 82 4) 5 6 10 12 15 15 18 18 21 21 24 24 24 26 29 3) 38 4) 4) BOURNVILLE : 5 12 7 19 26 3} a4 42 45 55 65 73 83 85 89 991106 | 110] 110] 112 M. HARRIS 2 + 7 9 14 17 17 22 22 | 27 32 | 37 | 42] 42 |.44 | 49] 54 56] 58 H. DOVEY 3 10 | 12] 14] 17 | 20 | 23] 28] 33] 36] 41] 43 | 45 | 50} 52] 54] SK] 34 5 10 15 21 31 38 44 46 53 56 56 59 69 75 80 85 87 91} tol] i A, AUSTIN 3 8 10 13 18 23 26 26 28 28 28 28 33 36 36 43 45 49 54 59 R. COLE 2 2 5 8 13 15 18 20 25 28 28 31 36 39 42 42 42 42 47 52 HOVE AND BRIGHTON: 5 10 17 25 32 37 44 49 51 58 65 72 7 85 9 95 95 98} 103.) 108 Cc. COLSELL 5 D. DALY UILDFORD 8 | 10 56 5 7 10 15 20 22 27 29 3) 36 4) 43 o}| 5| 10] 15] 17] 17] 22 | 22] 22| 27 | 29| 31] CLEETHORPES : 0 3 é 9 9 9 C, GRIFFIN Oo} i. BRIGGS 0 3 C 48 50 55 55 55 60 60 34] 37] 40] 40] 40] 43] 43] 48 3 15 15 WS] 7] 19) 24] 29] 34] 34] 40] 46] 49] 49 Ind. Scores | Positions 138 Ist. 68 2nd 70 Ist. 5t 82 Sth 41 4\ B. GARBITT | Totals} 4) 112 2nd 58 Stk “4 WW 6th 3rd 59 4th 52 108 7th 4tr 60 3rd 48 49 ati été 6 6 6 6 8} 10] lo] 10} J2] 12 15 17] 20] 20] 23] 26] 26] 26 26 1ith 0 3 3 3 5 5 5 5 5 7 9 12 14 14 17 20 23 23 23 12tt HEAT SCORES, CLUB POSITIONS AND INDIVIDUAL SCORES AND POSITIONS

aS JUNE 1971 Building the GRAUPNER ‘OPTIMIST’ In part two of his two-part report, Bob Jeffries discusses R/C installation on a plug so that the frequency could easily be changed, by first opening the hinged back of the case. The receiver/decoder follows current practice. It has a double tuned aerial circuit for better selectivity, and by opening the case access can be had to the crystal. The rudder actuator used is basically as the aircraft version, and has ample power to control yachts up to a medium size such as Optimist, but does not have sufficient power in my opinion to control the large ‘Q’ class yachts. The sail winch actuators are worthy of special mention. Physically they are the same size as the rudder actuator, but to obtain the power needed to operate the sails a much more powerful amplifier is used. This is too big to fit inside the actuator so a separate box is used, connected by plugs and sockets. This amplifier is rated at 5 watts, and at a line voltage of 4.8 volts the current is in excess of one amp. Four transistors are used in each output. These are fitted with heat sinks and are fitted to the metalwork of the case for better heat dispersion. The actuators have the usual feedback potentiometers, but to obtain sufficient movement of the drums are geared down from the output shaft. The full stick control gives five turns of the drums, and this amounts to about 12 in. of movement of the sheets controlling the sails, just about right for the average yacht. A static test of the power of these winches was made. They were mounted on their sides and a dead weight of 2 Ibs. attatched to a cord from the drums; this was lifted and lowered without any appreciable change in speed. No attempt was made to find the ultimate power of these units. On physical examination, the gearing was seen to be rather delicate, and also stalling the motors could cause damage to the amplifiers. Sufficient to say I am of the opinion that this power is adequate for any medium sized yacht, especially as the load of the sails is taken by the two actuators. Again I am of the opinion that this is not enough for the ‘Q’ class either in power or the amount of movement. The battery packs supplied are DEAC of 500 m/a JXOLLOwING the completion of the construction of Optimist, consideration had to be given to the most suitable equipment to give the controls required. It was decided that standard commercial equipment freely available should be used. This limited the choice considerably, as to my belief there are only two commercial types of winch actuators available at present. The kit referred to the Graupner equipment and sail winch, but it would not appear to be available on the British market yet. The other equipment was the Simprop Nautic 2 plus 1 which is marketed in this country through Mainstream and most good dealers. This equipment consists of a three channel digital transmitter, a superhet receiver/decoder, a rudder actuator containing its own amplifier, and two sail winch actuators together with their high power amplifiers supplied separately. Batteries and switches are all prewired to plugs and sockets and only need plugging together to complete. This equipment was first mentioned in this country in April 1969, but has had hardly any publicity, and few know of its existence, a case of the manufacturers ‘hiding their light under a bushel’, It would appear that all their efforts have been towards promoting the aircraft versions of this well known equipment. The Nautic follows the design of the Digi 5 range of aircraft equipment, except that it is only for three channels, which in our case is all that is needed. The transmitter follows current digital design and is styled in the well known Simprop style. The right hand stick controls the rudder and has a trim adjustment. The left hand sticks are double and control the two winches; one of these controls only has a trim control. A state of battery meter, an on/off switch, and a charging socket complete the equipment. Crystals are capacity. The transmitter operates off 12 volts, the receiver and rudder actuator work off one 4.8 volt DEAC, and a separate DEAC of similar capacity but of different shape powers the winch amplifiers. This makes the use of two on/off switches necessary, and care has to be taken to see that both are switched. This is a small inconvenience, as is the fact that three sets of batteries have to be recharged. One charger can do this easily. The installation of this equipment in Optimist caused no trouble. For readers with experience of aircraft installations the need for a_ shock-proof mounting to survive hard landings and crashes will be 227 SSL SSS

25T GEAR MECCANO GEAR RATIOS WHEELS 38) 19) = 201 25 25 19 444 —4 3g! 25!= 1,52:1 3a! -15!= 2.52:1 ay / -19 = 1.32:1 AOE 1.66:1 T z. -15 = 1,27:1 MECCANO GEAR WHEELS 1″ O.dia. 38T SIZES . 3/4″ Odio. 25T 9/16″ 0.dia. 19T 7/\6″ 0.dia. 15T Pont ys = 9/6s” 41/2″ foe . 1/4″ + 3/1000″ dia. 4 ae 4? 19T GEAR | 9 G A 1.3/4″ – 6 “NF 7/8″ — ‘ 1} 1/8″ dia. i Hin ” dia. arma dia [ ae ie oot 1 Sed ex Le 7/64″ dia. ; \/4 4-8.A. Waa hol 6.B.A. be ad fogke Tn. + J age 7 af stile, TeV4r« t* |i \J/4″ dia. 2.1/8″ 6 / my F 72 — wigs | mae t tu :& nee / 15 14 DANSON ‘MOVING CARRIAGE! VANE GEA * b J 37 a 3/64″ 3/8″ dia. tones = x 3/32″ 4.B.A y, rae a >–$$ — [ a /4″ + dia. \ys” ; SN tO. BA lers aLal | / ! &y \/4″ | fay Ai seaow 15 fs eye a E 2k fa ba 2 Spaces 5° and 10° ‘ : geeme 3 11 ay: oes MES ” fe 1/32″ ieneporefa ° Ber See EF 17 16 Y — 1/4″ + 3/1000″ dia. (/4″ + dia. 236 | —* os asAk we Ae iyae p IUNOAAONOUIIT DN 4 WOW Te ae a am) ev

JUNE O SERIES of articles on the construction of model racing yachts would be complete without mention of the vane gear. This fitting is the ‘brain’ Racing Model (no pun intended) behind it all; in essence it is a simple piece of machinery but nevertheless, if well constructed, is extremely sensitive and accurate in operation. Therefore, a high standard of workmanship is demanded and, unless the reader has more than Yacht Construction By C. R. Griffin Part Twelve average competence with metals and tools, the wisest advice would be to purchase a vane gear. 1971 No attempt will be made in this article to expound Notes on vane gear, and a moving the theory behind, to trace the development or to explain the precise use of the vane gear under com- carriage gear petitive conditions. These subjects are left to others more qualified in those particular fields. However, some explanations are needed to enable the beginner to select a type of vane gear. Secondly, no constructional article is complete unless reasons for various actions are given and comparisons are made. The vane gear, as the name implies, is operated by the wind acting on a vane or feather. The feather follows the movement of the wind and through a mechanism actuates the steering arm, the tiller arm the hull and the desired angle of the feather to the wind is obtained by turning the feather arm on its spindle. Note that the feather arm spindle moves off centre when the carriage is unlocked and self-tacking is in use. This is in contrast to the break-back type where only the arm parts move off centre and the major part of the vane gear remains on the centre line of the hull. The second major difference between the two types of vane gear is in the linkage ratio and linkage method. In the break-back type the linkage between the vane mechanism and the rudder is and hence the rudder. Enumerating the requirements of a good vane gear, it must be:- 1. Robust. Nothing can be more infuriating than a piece of equipment which is in constant need of repair. 2. Light in weight. The problem of weight is always foremost when considering any fitting for a model racing yacht. Problems of trim arise if a very heavy vane gear is fitted. 3. Accurate. Unless the fitting is accurate in operation and reliable in settings it will be a liability rather than an asset. 4. Sensitive in operation. When consideration is given to the strength of winds encountered on a midsummer’s day, the sensitivity aspect is only too obvious. Probably more vane gears fail on this point than on any other. 5. Easily adjusted and operated. A highly complicated mechanism incapable of quick adjustment or easy operation by the skipper will probably achieved by another pin and slot arrangement. This is capable of giving linkage ratios between 1:1 and 3:1, i.e. one degree movement of the feather will transmit one degree of movement to the rudder in the former ratio. It will require three degrees of movement of the feather to move the rudder one degree in the latter ratio. The position of the linkage pin, which determines the linkage ratio, is instantly adjustable. On the other hand, the movement of the feather on the cause excessive delay resulting in the loss of points in competition. a, In this case the feather-balance arm is ‘locked’, i.e. restrained in a straight line. Any angle can be obtained by rotating the arm on its spindle. Basically, the vane gears in use today fall into one of two categories, namely the ‘break-back’ type and the ‘moving carriage’ type. In the former, the arm which carries the feather and the balance weight is in 4 Le two parts connected by a ‘pin and slot’ arrangement or meshed gears. On the windward beating courses, when the self-tacking action is employed, the arm is ‘broken’ and adopts a position in which each part of the arm lies at a predetermined angle to the centre line of the hull. In the ‘unbroken’ condition, i.e. when the arm parts are locked in a straight line, the desired angle of the feather to the wind is achieved by turning the whole of the arm mounting device. Fig. 89 shows a simplified arrangement of this prin- ciple. The moving carriage vane gear has its self-tack motion controlled by lines from the main boom either through the slide on the main horse or through the ‘triangle’. The feather and counter balance arm is a rigid bar. The beating angle of the moving carriage vane gear, on self-tacking, is achieved by using two meshed. gear wheels which, by a ‘sun and planet’ motion, allows the carriage and hence the feather to for the new tack. move to the pre set angle. When self-tacking is not employed, the carriage is locked on the centre line of SE In this case the feather-balance arm is ‘broken’; as the yacht heels the weight of each part of the arm causes the arms to move to the ‘heeled-down’ side. When the yacht comes in to the bank of the pond and is turned, it is heeled on the opposite side to which it was when it approached the bank. The weight of the arms causes the gear to ‘flop’ to the opposite side of the hull, the vane gear is then set Fig. 89 PRINCIPLE OF THE BREAK-BACK FEATHER-BALANCE ARM 237

{ {ae MODEL BOATS moving carriage vane is transmitted to the rudder through the gears with an extension arm on one gear, through a ‘push-pull’ motion to the rudder tiller arm and hence the rudder. The size, or to be precise, the number of teeth on each of the gear wheels fixes the ratio of movement of the feather to the movement of the rudder and remains constant so long as that pair of wheels is engaged. Two 32 tooth wheels will give a 1:1 ratio; similarly, one 32 tooth wheel meshed with one 16 tooth wheel will give a 2:1 ratio. Unless an elaborate system of wheels is employed the ratio is unalterable and, except when the length of either the gear extension arm or the rudder tiller arm is varied from equality, any movement of the feather will produce a constant reaction by the rudder. The use of a variable tiller or extension arm rather complicates the mechanism and its advantage is usually outweighed by the disadvantages. The only other major difference between the two types is the gyeing device. Gyeing is the ability to make the boat change tack at some distance from the bank and to return to the same bank. The gyeing device not only enables this tactic to be used but allows for a variation of the distance from the bank at which the change of tack occurs. The break-back Item 2. Item 3. or jig. Item 4. Item 5. Item 6. Item 7. Item 8. O CENTERING SPRING TRIANGLE from 4 in. to 7/32 in. for the upper ¢ in. If this is done, remember that the bores of items 11, 12 and 13 also need to be reduced. Pivot pin — material, ¢ in. stainless steel rod — sizes as shown. Machine or file the point to an angle of 60°. Lap the pivot pin into item 6 using metal polish. The final fit should be free from binding without any side play whatsoever. Carriage stops — material, brass and/or nylon NOT TO SCALE (> G shown. It is advocated that this item if no other is machined with the bore reamed after item 5 has been soldered in position. An ideal friction reduced bore would be as that the diameter of the spindle be reduced LAYOUT OF VANE AND OPERATING GEAR TO BOOM Sun wheel — material, brass Meccano 25 tooth gear wheel—sizes as shown. Ideally, this wheel should be bored to $ in. + 3/1000 in. and machined to 3/32 in. thickness using a collet type holder. However, satisfactory results can be achieved by sawing and drilling. Whatever method is used, file the teeth edges carefully to remove any burrs. Use a round ward file. Planet wheel — material, brass Meccano 19 tooth gear wheel — sizes as shown. Once again greater accuracy is obtained by boring, ensuring a tight fit upon item 6. Silver solder to item 6 and then clean and remove all burrs from the teeth edges. Feather spindle — material, brass — sizes as shown in inset 1. If it is desired to have a locating shoulder for item 11, it is suggested Parts list: Item 1. Main column or pintle — material, brass — sizes as shown. Machining from solid gives the best results but the column can be built by silver soldering a baseplate to + in. dia. Baseplate — material, } in. thick Tufnol or Perspex — sizes as shown, The distance between the centres of the main column hole and the feather spindle hole is determined by the outside diameters of the gear wheels used. In this case a 25T-19T set is used. Score the centre line of the baseplate, this is needed when setting and calibrating the gear. Top-plate — material, as item 2 — sizes as shown. To be as accurate as possible, cut and drill the two plates from a common pattern type uses a spring or rubber tension on the two parts of the feather arm to produce the gye and can be rather capricious in performance when long gyeing is attempted. The gyeing action of the moving carriage vane Operates on the carriage itself or on the ‘triangle’ or a combination of both. It is, therefore, more powerful than the break-back type using the same spring tension. A Moving Carriage Vane Gear Fig. 90 gives the details of a moving carriage vane gear which has been developed over the years to be one that has the minimum number of parts. Basically, the amount of lathe work is small but naturally a better gear is produced if as many parts as can be are machined. A vane gear, identical to the one illustrated, has been made using only an electric drill and has been adequate in operation. rod. Alternatively, the pillar from an expanding loose leaf binder will suffice. TILLER ARM CARRIAGE TACKING LINES 238

1971 JUNE 18 Ve”— | = 15″ = — sizes as shown. The stops illustrated are mounted on a single 6 BA bar with nylon support pieces at either end. Alternatively, individual stops can be mounted either side of the centre line of the hull, Item 9. Carriage centre lock — material, Tufnol/ stainless steel — sizes as shown. A centre line scored along the top face of the lock is of assistance when setting the gear. Item 10. Support pillars and screws — material, Tufnol or hard plastic — sizes as shown. Item 11. Dial fixing flange — material, brass — sizes as shown. Note that two securing screws are used; this prevents the dial from turning on the spindle. Item 12. Dial — material, white Perspex 3/16in. thick — sizes as shown. If the dial is to be marked in increments of five degrees as illustrated, it is useful to make a paper template for, say, 90°. The dial is either riveted to its flange or screwed; ensure that the rivet or screw heads are countersunk. Item 13. Feather arm — material, Perspex — sizes as shown. Do not make the feather spindle hole too large otherwise there will be a tendency for the Perspex to crack under the strain of the clamping screw. Item 14. Lower bearing collar — material, PTFE or Tufnol or hard plastic — sizes as shown. If the collar is made from other than PTFE it is advisable to cut knife edges on the upper face to reduce friction. Item 15. Upper bearing collar — material, as item 14 sizes as shown. Ensure that the collar is thick enough to keep the sun wheel teeth fully engaged with the planet wheel. Item 16. Extension arm — material, brass or stainless steel — size as shown. It is essential that the distance between the centres of the main column hole and the linkage arm hole is identical to the distance between the centres of the upper pintle and the linkage arm hole in the tiller arm. Item 17. Linkage arm — material, brass or stainless steel — size to suit particular layout. In the gear illustrated the linkage arm was made from 16 gauge stainless steel wire bent as shown. Alternatives are the use of model aircraft spring links or 6 BA screwed brass rod and trunnion pieces. Item 18. Feather — material, $ in. thick balsa wood — total area of feather should be approximately four to five times the area of the rudder. Ensure that the wood is perfectly flat and waterproof with one or two coats of filler rubbed down with 400 wet-or-dry paper. Item 19. Balance weight — material, lead or stainless steel. The exact size and weight of this item is best found by ‘trial and error’ when the feather arm is being balanced. Avoid the use of too heavy a balance weight, it is better to lengthen the rod to give a higher resulting force. Lock the balance weight in position by one or two locknuts when balance has been obtained. Assembly Silver solder the planet wheel, item 5, to the feather spindle, item 6, Ream to } in. diameter the bore of the feather spindle and lap item 7 to item 6 to pro- duce a free fit. Insert the main column, item 1, into baseplate, item 2, fit sun wheel (4) onto column. Fit and lock pivot pin (7) into baseplate. Position the planet wheel and feather spindle assembly and check that the clearance between the gear wheels is sufficient to prevent binding but not so excessive as to cause the teeth to jump. Elongate the pivot pin hole to correct. Remove sun wheel and base plate from column, place lower bearing collar (14) onto column, then baseplate and upper bearing collar (15). Fit sun wheel complete with extension arm (16). Slightly enlarge feather spindle hole in top-plate (3) if pivot pin has been moved and then place top-plate in posi- tion. Insert support pillars and screws (10), fit flat headed screw. Rivet dial (12) to locating flange (11) using 1/16 in. copper rivets then fit dial and flange on to feather spindle locking into position with the two securing screws. Place feather into slot in feather arm and lock into position with 6 BA screws. Balance the feather arm by using a length of 4 in. rod fitted into clearance size brass tubing and adjust the lead balance weight so that the arm remains in any selected position. Alternatively, the feather and feather arm can be balanced on the pivot pin prior to assembly of the gear. Clamp the feather arm onto the spindle. Hold the vane gear by the column base and check that, by blowing from a distance of about three feet, the feather actuates the extension arm. If all is satisfactory, remove the flat headed screw and slide main column from the carriage assembly; the two collars and the sun wheel will fall free. Locate the column on the deck on the centre line of the hull and secure with ¢ in. x No, 2 brass screws. Note that it is important that the column be on the centre line and in an upright position; it is advisable to check this position using odd-leg calipers and dividers. Drop the incomplete carriage assembly back onto the column and, holding a pencil on the centre line of the tab of the baseplate, scribe a line by moving the carriage 60° off centre on either side of the centre line of the hull. Remove the carriage assembly and 239 EE ee ee ee

JUNE fit the adjustable carriage stops (8) 4 in. forward of this line using # in. x No. 2 brass screws. Replace carriage and align the centre line of the baseplate with the centre line of the hull and fit the carriage centre lock (9). Ensure that as the lock is slid over the tab of the baseplate the carriage does not move. Remove carriage, fit lower bearing collar then replace carriage. Lift carriage and insert upper bearing collar and sun wheel, lower carriage and fit flat headed screw. Check that as the carriage swings it passes freely over the centre lock and is arrested by the stops. Fit the pushpull linkage arm of the appropriate length between the extension arm and the rudder tiller arm ensuring that the two arms are parallel. Lock the carriage in the central position and, whilst holding the extension arm, loosen the screws on the dial flange and turn the dial until the centre line arrow is facing fore and aft. Tighten the fixing screws and check that any ‘play’ allows the feather arm to move equidistant from centre. (Try sighting on the rudder pintle.) Move the carriage stops so that they are the same distance from the base plate tab. A piece of % in. wide brass strip will suffice to use as a feeler gauge between the stops and the tab. Unlock the carriage and move the carriage up to the port stop. Check the number of degrees that the dial has moved. Repeat for the starboard side. If everything is accurately set and fitted the angle should be the same on either stop. Should there be any difference, centre the carriage, check with centre line, lock the carriage and recheck stops. Assuming that the carriage moves an equal amount either side of the centre line, set the stops so that the feather arm lies at 35° when the carriage is hard up to either stop. Note that the feather spindle moves off to mount guns in turrets which would turn and theoretically allow for all-round fire. This necessitated a low freeboard to allow the guns to be trained in any direction. He intended these principles to be incorporated into a sea-going warship with a full rig, which was considered necessary in the early years of the steam engine to conserve fuel on long voyages. This was considered to be a most unsuitable combination by many people. Edward James Reed, the Chief Constructor of the Navy, did not share the views of Captain Coles. He accepted the principles of revolving turrets and low freeboard for coast defence monitors, but would not consider putting masts and sails on them for stability reasons. His designs produced much shorter vessels than the earlier designs such as H.M.S. Warrior, and they were thus more manoeuvrable. His general aim was to produce handy ships which could utilise endon fire without sacrificing the weight of their broadsides. One of the first was launched in 1865; this was H.M.S. Bellerophon which had high sides and was 241 es plate arms by quadrant hooks in the forward pair of holes. The lines are led forward, crossed over and attached to the arms of the triangle. As the main boom moves off centre it pulls the forward arm of the triangle to that side of the hull. This movement is transmitted via the tacking lines to the carriage which in turn moves off centre until arrested by the carriage stops. Gyeing is achieved by using a spring attached to a bowsie running along a jack-line. The other end of the spring has a quadrant hook which is placed into the after pair of holes in the baseplate arms. Movement of the bowsie on the jack-line will cause the spring to exert a force, determined by the amount of movement of the bowsie on the vane carriage. This force will overcome the force of the wind on the feather and when the yacht assumes an upright posi- tion will move the carriage to the opposite tack. General Notes Although gear wheels by Meccano have been men- tioned it is possible to obtain precision gear wheels in brass or stainless steel. Should there be so much upward movement of the sun wheel as to cause it to override the planet wheel, a third washer will need to be fitted above the sun wheel. Friction is the greatest inherent problem of the moving carriage vane gear, it is therefore essential that all clearances allow for free movement. The application of a little light machine oil often cures stickiness. the sinking of this early iron warship ON the night of 6-7th September, 1870, H.M.S. Captain sank of Cape Finisterre, on the coast of Spain, in a South-West gale whilst heading for Portsmouth with the combined Channel and Mediterranean fleets under the command of Admiral Sir Alexander Milne. She was an iron-hulled man-of-war which had been built to test the ideas of Captain Cowper Phipps Coles, who went down with the ship. His ideas were EE centre when the carriage rotates. The carriage tacking lines are attatched. to the base- P. E. King outlines the story behind H.M.S. CAPTAIN 7 1971 fully rigged in addition to her engines. Her heavy guns were mounted in an armoured citadel amidships. A smaller battery was mounted in the bows behind armour to give the desired end-on fire, but the weight of it affected her sailing qualities and in later designs the end-on fire was supplied by guns in the citadel firing through recessed gun ports at the corners. These designs potentially retained the seagoing qualities necessary in a sailing ship. The Captain had the greatest length to beam ratio of any capital ship for the next 35 years, coupled with the lowest freeboard of any British sea-going armoured ship. The result was that she was unstable and sank in the heavy weather. The sails were worked from a flying or hurricane deck which passed over the turrets and the masts had tripods to reduce the amount of rigging needed to support them, which would otherwise impede the arc of fire from the turrets. These characteristics were not suited to a sailing ship although it required a disaster of the magnitude of the loss of the Captain to convince many people of this fact. The ship was built by Lairds, being laid down on 30th January, 1867 and completed in January 1870 at a cost of £335,518. She was 320 ft. by 531 ft. by 241 ft. and 7,767 tons. Her armament consisted of four 12-inch guns and two 7-inch guns. For further information on this ship the book on British Battleships by O. Parkes and ‘H.M.S. Captain’ by A. Hawkey are recommended.