JULY 1972 15p U.S.A. & Canada Seventy-five cents HOBBY MAGAZINE

MODEL BOATS induction O.P.S.60. He also has a shelf full of trophies which Ogee has won for him in A Class Multi 34 c.c., including the Keighley International Trophy which he has won two years in succession. Nova is a development of Ogee, but it has a much deeper convex bottom, and parallel spray strips running along 60 per cent of the hull. Ogee and Nova work on the same principle as Opus and Kali, and being a new concept in design new steering techniques should be applied. When steering round a buoy near maximum rudder should be applied so that the hull makes an extremely sharp turn, not in the fashion of normal proportional steering as this is liable to flip the hull. It is recommended to adopt the same technique as with reed equipment, i.e. all or nothing. This may sound rather drastic but you will find that it steers the best and fastest course possible. Some people seem to consider it essential that fast hulls should turn on a sixpence to be any good, my hulls will not perform this amazing feat which I consider to be a highly dangerous and over-rated pastime. What they will do is give you a fast, accurate turn which is very easy to control. I hope that by producing these hulls the field of competition will be opened up and some new names brought to the forefront. For too long now a closed shop attitude towards beginners in boating has been having a stifling effect on the whole sport. I do not recommend these hulls for complete beginners as they are rather fast, fast enough I feel to lead the way in high-speed work in England, but for anyone with some experience in boating they should prove very worthwhile. sometimes the case. The dial is marked so that it is THE VANE ASSEMBLY IS POISED ON SIMPLE PINTLE BEARING IT IS ESSENTIAL THAT VANE IS OF LIGHT WEIGHT TO PREVENT VIOLENT “OVERSWINGS” DURING WIND SHIFTS COUNTERBALANCE WEIGHT ee BRASS TUBE divided into segments of 10 degree spacing. The instrument itself consists of a base plate made of 4 in. ply which should ideally represent a scale plan of the lake. At one end of this board, and placed centrally, is a wind vane, similar to that mounted on the model yacht. Under this vane, a dial identical to that on the vane gear is then drawn on the board to indicate the wind direction. A disc for each suit of sails, made of 7s in. ply, is arranged to slip over the brass tube housing the vane pintle and this disc can be revolved as desired. It is marked in an identical manner to the dial on the yacht’s vane gear with the exceptions that the impossible sector is filled in solid and four annular rings are marked on its face. Finally, a small clamping device is arranged to hold the ply disc firmly after adjustments have been made. ~1/4″ PLY BASE PLATE SUPPORT BLOCK FOR DISC A useful Tuning and Sailing Aid By Geoff Draper NUT LET INTO PLY BLOCK SECURED WITH ARALDITE (PSHE instrument was primarily conceived because I habitually have to sail alone and also because the conditions are such that unless an accurate course is laid, I am in danger of having to walk miles to retrieve the model. The weather conditions near the Gulf of Lyon often produce very rapid changes in both direction and speed of the wind. It is not uncommon for a flat calm to change into a near gale force wind in a matter of a few minutes. With a wind vane I am able to glance at the vane the moment before launching the model and check the probable direction of the course. It was realised that the instrument could be de- veloped not only to indicate accurately the swing of the wind but also to aid the tuning up process. A similar instrument is mentioned but not described by Mr. Priest in the book ‘Model Racing Yachts’. The device was used in conjunction with a moving carraige type vane gear having a dial mounted on the vane spindle and not on the moving carriage as is 280 (who lives in France) The operation and uses of the instrument When arriving at the lake the instrument is set up in an unobstructed position with the base board lined up with the actual lake. Thus a central line down the centre of the board will represent a central course down the lake. Imagining top suit conditions, the appropriate disc is slipped over the vane tube and the vane placed in position. The wind vane will then show the wind direction relative to the lake. The disc is then revolved so that the 0 degree marks correspond to the wind direction. As most good yachts can make a course of roughly 40 degrees to windward, with a vane setting of around 30 degrees (although this admittedly depends on many variables, particularly wind strength) one can sight down the two angles marked 40 degrees and this will indicate where the model should arrive at the bank on either tack. Once the tuning up has been achieved the impossible sector for the top suit can be marked on the

JULY Sketch at bottom right is Fig. 1. By sighting along limit of impossible sector it can be seen that the yacht would not quite make the length of the lake in one wind as shown. leg with 1972 simplest method of using the device is to remember to line up the 0 degree mark on the disc with the direction of the wind indicated by the wind vane and then read off the figures in the columns which are then lined up with the direction one requires to sail — usually this is in the direction of the finishing line. There is one other interesting by-product in the use of this device. As the various course settings are built up it becomes rather like ‘fairing up’ the lines of a yacht in that if one vane angle for example is obviously ‘out’ and has little relation to its neighbours it indicates that there is something wrong with the train. Also one gets a good idea of the relative difference in angles between the true wind and the ap- the parent wind by comparing the figures indicating the actual course. I have entered a couple of possible settings on the disc and it will be noticed that for a broad reach with the wind at 90 degrees the vane angle (taken from the forward position) is only 70 degrees; allowance for the apparent wind has to be as much as 20 degrees. It must be stressed again that this instrument is for the ‘loner’ and the novice — probably the best skippers sail by instinct and their burgees. Also it is only intended to be an aid to show changes of wind direction and provide a means of indicating the change of trim required when this takes place. Finally, it is important that there should be a separate disc for each suit of sails. It is also very interesting to stand behind the instrument’s vane and watch how the yacht reacts to changes of wind direction. As one might, or might not expect, it is usually sudden changes in wind direc- tion rather than speed that cause the yacht the most trouble. Gusts are often accompanied by a violent DISC TURNED 180° FOR wind shift. WIND ASTERN 20 disc. From now on, under these conditions, one can get a good idea of where the model is likely to arrive at the bank under any given wind direction. A typical windward set up is shown in Fig. 1 where the wind is 20 degrees to starboard off the centre of the lake (a good skipper will have noted various reference points measured from the starting position which give him a quick check on the true direction of the wind). We now come to the annular rings. The outer one represents a column giving the optimum vane angle, the central column the main boom settings and the inner one the jib boom settings. Once these settings have been established they can be entered up in the appropriate column, in this case a course of 40 degrees will be stated beside the 40 degree mark on the ces i movable disc. As more courses are sailed and more figures obtained, these can be entered in the columns until one has built up information on likely vane and boom settings over a wide range. This procedure can be very instructive, particularly if the boom angles are checked in actual degrees as well as by the markings used to denote the sheet settings. From then on the instrument can be used as a guide to probable settings for any course. I say, ‘guide’, because there are so many variables that it is impossible to be accurate. For example, the wind vane will indicate that during a board the wind will be constantly changing direction if only minutely. Added to this are likely to be variations in wind speed which will immediately affect the optimum vane angle. The 281

MODEL BOATS BOATING FOR BEGINNERS (new series) Let’s Go Sailing BASIC INFORMATION TO HELP YOU GET STARTED IN YACHTING [HERE is little doubt that model yachting has re- which it is a small step to membership of a club and were making tremendous strides in design development. A part of the resurgence of interest is due to R/C sailing finally beginning to attract wider support, but only a part; competition and sport ‘free’ sailing were already noticeably on the way up when in a day, each heat comprising two boards, once up and once down the lake. On a lake such as Fleet- low, although, in fact, during this period the devotees signs of growing R/C interest became evident. Things tend to go in cycles in modelling, and after a dozen years of concentration on competition power boating, there are indications that the emphasis is swinging slightly away from plain R/C speed and steering events and strongly towards multi-racing and scale. Similarly, there is a small drift away from aircraft. A lot of this can almost certainly be attributed to noise problems causing loss of, or restriction on, use of waters and flying grounds. The model yacht scores heavily on freedom from noise, smell, oil contamination, etc., and can be sailed in many places where fishermen, house owners, full-size boat owners, park keepers, etc., would object most strongly to engine-powered craft. One of the joys of yachting, frequently mentioned, is that wind is free. Once you have paid out for materials, fittings, etc., the outlay is nil. Even with radio it is only the cost of batteries or the minute amount of current needed to recharge a built-in power supply. You might decide to have a new suit of sails or new cordage now and then, but yachts can last a long time; a famous example is the 36 in. etal over 40 years old and still a top competition oat. ‘ move on to larger or more competitive models, from cently been making a strong comeback after a period of several years when general interest was To sail a vane yacht you need a water accessible all round, and after the boat is tuned and the skipper has learned to sail it, another boat to sail against is desirable. While sailing a model solo is enjoyable, few people can remain satisfied indefinitely without having something to compete against. Part of the reason for the growing number of R/C yachts is that they can be sailed on waters not completely accessible, and sailing alone is slightly more interesting, though even here the urge to race someone soon emerges. Inevitably, some people build a yacht and sail it for a summer or so, then drift on to something else. A proportion, however, get the competitive bug and 284 many years of enjoyment and exercise. Exercise? Well, you can sail a dozen or more heats in a race wood, which is 800 yards long, the skipper and mate cover over a mile each for every heat. You get exercise! Since we have discussed radio yachting quite a bit in the last half-dozen issues, for the moment let us consider vane boats only. We say ‘vane’ boats because this is the way modern vessels are steered. Originally, models sailed on sail trim only, with no rudder or a fixed one. Some 80 years ago lead weighted free-moving rudders were used; as the boat heeled, the weighted rudder ‘fell’ to one side and steered the boat away from the wind. Its sail trim brought it back until the next heel. A good skipper had a pocketful of rudders of various weights. Early in the 1900s, George Braine invented the method of steering which still bears his name. The pull of the sheets (lines controlling the sails) is transmitted to a spring-centred quadrant on the rudder head; the leverage is adjustable by hooking the sheets nearer to or further from the centre line. Braine gear made sailing much more precise, and it was used until the 1930s, when the vane gear arrived. Small models even today use the Braine gear, and some elements of it are used on a few modern large racing models, primarily to ‘cushion’ wind gusts, but on the whole it is considered obsolete, since the vane gear is infinitely superior and can be used effectively on all points of sailing. One aspect of Braine steering should be mentioned. Boats using it had to be designed to be directionally very stable, i.e. they had to travel straight (in fact the balance between sail trim and gear produced a line of gentle curves, the chords of which corres- ponded with the required course). A boat designed for Braine steering usually had an elongated skeg joined to the fin keel, and a shallow but broad rudder. This layout is not suitable for vane gear, and so to change an old boat to modern steering means a certain amount of structural modification. We will return to considered. this subject when boats themselves are i Vane gear made its first appearance in competition

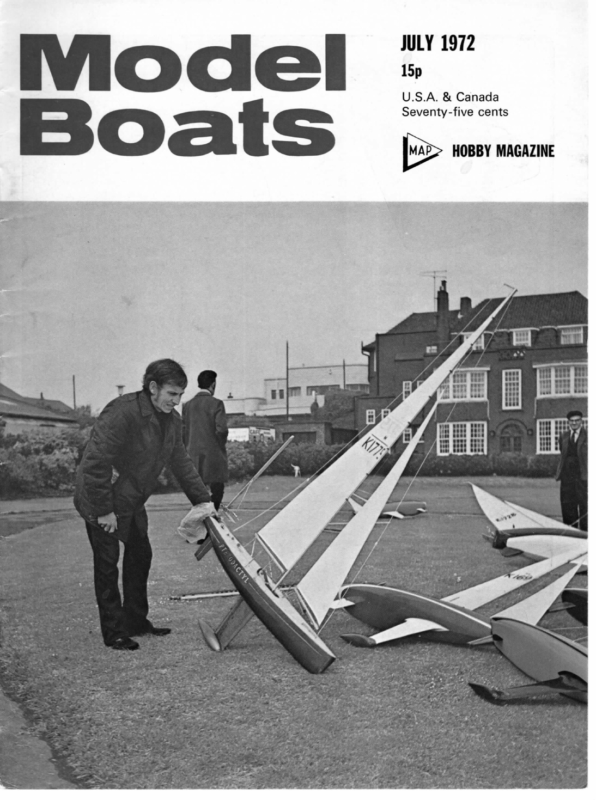

JULY In the picture opposite, the tracks of the boats have been dotted in. The near one has just been turned and will get its nose further to windward as its sails and vane settle it down; it has been turned past its future course in order to ensure that the jib is filled. Note that this boat has sailed more off the wind but obviously much faster than its opponent and has plenty of time to turn without danger of collision despite having started from the lee berth. The starter (arrowed) is about to send off the next pair while one of the pair to follow is bringing his boat out. in the middle 1930s. It was rapidly developed, and though its advance was delayed by the virtual cessation of model yachting from 1939-1945, within two or three years of the resumption of organised model sailing, all new boats were being fitted with it and most older boats converted to use it. All that need be said at this juncture is that proper sail trim and vane setting, the gear will sail a yacht on an absolutely constant course relative to the wind. If the wind shifts 10 degrees, the course of the yacht will change (in relation to the lake) by that amount. The yacht will respond to every flaw in the wind, but by the same token, it will immediately resume its original heading as soon as the wind returns to its original direction. Racing. Yachts are raced in pairs on the tournament system, i.e. each yacht sails every other. Taking a simple four-yacht example, in Heat 1 A sails B and C sails D. In heat 2 A sails C and B sails D. In heat 3 A sails D and B sails C. Every yacht has now sailed every other so a complete round has been sailed; note that a round must consist of one heat less than the total boats sailing, ie. 4 boats—3 rounds, 20 boats —19 rounds. Each heat consists, for each pair of boats, of two boards. Ideally this is once up and once down the lake, a beat to windward and a run to leeward, which can happen when the wind is straight down the lake, or within say 30 deg. of the centre line. Because good windward sailing is a more severe test of design and handling skill, the winner of a beat scores 3 points and the winner of a run 2. Thus 5 points are at stake in each heat, and boat’s ‘possible’ score is 5 x the number of heats. Where an odd number of boats are entered, each boat has a bye with no score; the number of heats now equals the number of entries but the ‘possible’ is 5 x (heats 1). Where a race is held with the wind blowing square across the lake, the yachts are reaching; score for winning a reach is 2, so that on rare occasions scor- 2 SR RC 9 SR RC sail off on their first leg. Should the boats touch each other, a whistle is blown and the boats must resail that board, either then or if this would cause too much delay, at a convenient time later. On reaching the bank at the end of the first leg or tack, the skipper (or mate) turns the boat with a pole (or hand) on the lee bow until the jib is full and drawing. He may not move his feet or impart way to the boat and he must not turn off in such a way as to cause a collision or he faces disqualification and loss of points on that board. If he wishes to adjust the trim the boat must be stopped. The self-tacking action of the vane is automatic, and normally the mate will pole her round on the other bank, and so on, till after three or four legs she crosses the finishing line. As each pair of boats starts, the next pair enters the water and are got away after a safe interval. Thus a ‘procession’ of pairs of boats make their way up the lake, unless a poorly trimmed one lags behind, when it may be overtaken by the following pair. At the windward end of the lake the boats are lifted out and retrimmed, spinnakers rigged, etc., for the run back, conducted in the same way except that the boats travel faster and in good conditions should run straight down the lake without coming into the bank. Then it’s retrim for the next beat. This brief account of what happens in a race necessarily omits many of the finer points and rules, but if you’ve never seen a race it gives some idea Next time we will move on to choice of boat. and may encourage you to have a go. pee Southampton M.P.B.C. Ornamental Lake, Ave., RC MR. L. FISH TROPHY. 9 RC RC Crosby M.C. Coronation Pk. 11 a.m. SR. 30 RC Oldham & West Pennine M.B.R.C. Alex- RC RC 9 Birkenhead M.Y.P.C. Gautby Rd. 11 a.m. 23 SR RC Southend M.P.B.C. Southchurch Pk., 11 a.m. St. MR. plus Electrics. No fee. Woburn H.C. Duncombe Breeches. 11 a.m. Mayesbrook M.E.S. Mayesbrook Pk., Lodge including Concours. 10p per event. paede M.B.C. Roundhay Park. 11 a.m. St. 9 SR SP 9 Huddersfield $.M.E. Highfields. 11 a.m. SR. Scale only for MAGHULL TROPHY. RC. St. RC Midlands RC SP 9 9 SR a.m. SR. Nom. St. Sp. (Sp. in 2 classes — up to 6.0 c.c. up to 10 c.c.). 23 2 SR confirms ‘Ready on the right?’. ‘Ready on the left?’, calls ‘Stand by’ and blows the whistle. The boats are released, without imparting any way to them, and Liverpool M.P.B.C. Walton Hall Park. 11 RC South On a good racing day the wind will be blowing down the lake towards the clubhouse end. Two buoys, usually about 12ft. apart, provide starting positions, and skippers have a choice of starting berth for half their beats, their opponent having choice at the other end. Which skipper has choice for which heat is shown on their race cards. The boats are placed in the water, pointed on the longer tack, the starter GATTA. Bradford & Shipley S.M.E, 16 23 2 and 3. YORKSHIRE M.P.B.A. ANNUAL TEAM RE- 2 16 ing may be ‘two each way’. In practice, the wind is usually biased to one end or other of the lake, enabling the O.0.D. (Officer of the Day) to score 3 and 2 or, if the wind is from the opposite direction, M.P.B.A. JULY REGATTAS North p. RC. St. (CRUSHAM TROPHY). & Southampton Common. MR. 3.5 c.c. 6.5 c.c, 5p per boat. One boat per event. Welwyn Garden City S.M.E. 11 a.m. St, 15p all day, Mortlake — see page 282. & Hove S.M.E. Hove Lagoon, RC SP 23 30 SR SP St. Slalom & Duration, 20p incl. 30 CHAMPIONSHIPS. Scale 16 Witton Lakes, Birmingham. 11 a.m. PILOT Funct. Clapham M.P.B.C. Long Pond, Clapham. 23 RC a.m. Brighton Wickstead M.Y.P.B.C. Kettering. 10.30 a.m. Wicksteed M.Y.P.B.C. Kettering. 10.30 a.m. 10p. RC 16 SR NATIONAL Barking, 11 Knockout. 16 andra Park, Oldham. 11 a.m. St. Sp. SR. Nom. Cascade. Sp. 20p — SR. 5p — Sp. 1972 St. Albans M.E.S. Verulamium. 11 a.m. SR. 10.30 a.m. St, MR. 10 mins. 25p. 11 a.m. St. F3 up to 14 c.c. and electric 80 to 100 watts. 10p per boat. Victoria RC N. RC 285 Victoria Park. 11 a.m. MR. 1 hr. Endurance. Pre-entry to: D. Stevposers 30 Valley View, Greenhithe, Kent. 25p. plus Scale Ships. 12p. M.S.C. Funct. Scale. No fee. Dover M.C, Kearsney Abbey. 11 a.m. St. MR. 10p per event. Welwyn Garden City S.M.E. 11 a.m. 15p. GRAND REGATTA, Victoria Park. ag a.m. 10 Mote Park, Maidstone. M.P.B.C. Cvgnets

— JULY At the fore end of the wheelhouse I have positioned a pot hauling winch, which can also be used for the landing derrick. This ore is a Miller type! There is also a warp tensioner at the fore side of the hatch. Radar The radar drawn is drawn to scale and is as stated a ‘Marconi’ Raymarc 8 in. This, as with the winch, is built from scrap, and is mounted atop the wheelhouse. 1972 think that it is self explanatory and is only box construction. As a painting guide I will add that the hull is red matt under-water with a white waterline. Numbers are white on a black ground with red shadow. The hull topsides are varnished, but of course can be any colour one wishes. The deck is light blue. The winches are a dark green; give all detail at least two coats of gloss. All hatches are brown Humbrol — shade number9 fits exactly. Conclusion I have not done any describing of the small detail as I That’s about all I can say. I wish you luck in building and will help anyone that is in trouble with any point. COMET Part Three (conclusion) By E. F. Amiss 42 in. R/C sailing catamaran, M.M. Plan No. 1139, price 75p post free. Fix a brass screw eye to inside of each hull, approx. | in. to rear of mast and one to centre of front bow cross member. Three bowsies are now shaped and drilled from 1/16 in. brass or alum. as sketch. Two brass pulleys are required, construct these from 14 in. of 5/8 in. x 5/8 in. brass for the housings. The housings are drilled and filed from the solid. The small ring ‘A’ is part of the solid, and please GOOSENECK This brass fitting is quite straightforward to make; follow the dimensions given, assemble and epoxy to mast 4.3/8 in. up to centre of fitting. The boom fitting must lie parallel with hulls. The main sail rigging wire is attached to the gooseneck, close to the mast, pulled taut, twisted and soldered. Drill and tap 6BA where shown and secure with 6BA screw. Approximately half way up the mast, bind the main sail rigging wire to it, epoxy over the binding, this will ensure a close fit of main sail to mast. This completes the mast. MAIN BOOM One 18 in. length 3/8 in. diam. mahogany or ramin. File one end to fit brass sleeve of gooseneck and glue in place. Round off the other end. Attach three brass screw eyes where shown. A clearance hole for sail attachment wire is drilled through each end of the boom, one end of wire is beaded and threaded through holes, drawn taut and bound and soldered at final end to prevent slackening. Sundry small fittings are now made in brass as per sketches. The three rigging tensioners are scraps of + in. diam. rod, drilled and tapped 6BA., with a clearance hole at top for entry of rigging wires. Insert port rigging wire, cut to required length, and silver solder a bead on the end. Repeat for starboard wire and finally about 6 in. of wire is beaded and threaded through the third tensioner for the foresail attachment to bow. From 1/16 in. diam. brass scrap wire form three hooks and silver solder them to the heads of three 6BA screws. One is inserted in each tensioner. 289 note one is at 90° to the other. Now cut the two fixing lugs from 25 gauge sheet brass, bending to shape as shown. Two small brass U rings are now made to attach the pulley housings to the fixing lugs, which are drilled to receive them. Attach pulley housings and rings to fixing lugs and solder ends of U rings underneath. Turn the two pulleys from brass scraps and close running fit. Drill the housings and fit pulley, riveting in place. Test for freedom of movement. Both pulleys are now attached to slatting where shown, and the fixing plate lugs are bent under to retain them. One final fitting, the brass line guide, consists of two 1/16 in. thick plated brass and one short length of 4 in. diam. copper or brass thin tube, which is bent to angle shown and silver soldered to one of the plates. Drill the plates to bolt together, the bolts passing through between the slatting, and fix in position shown on plan. This completes the fittings. CLUTCH ASSEMBLY This consists of three bearings, one clutch assembly with hollow shaft ‘A’ and one clutch assembly with winch drums ‘B’, also a clutch selector arm and fork. The above is attached to a 6V motor ona 4 in. plywood baseboard. Commence by cutting to size the } in. plywood baseboard and fit the motor where shown, length of assembly being important or you will not get it in the cabin. Some lathe work is necessary here, but very well worth the effort as it works faultlessly. Clutch assembly No. 1 (see exploded view) is turned from a 14 in. length of 7/8 in. or 1 in. diam. brass rod. There is sufficient length for chucking and parting off. Make certain there are no sharp edges left on the O.D. of drums; form a slight radius to them, to prevent chafing. Winch walls are approx. 1/16 in. thick and clutch plates 1/8 in. Clutch assembly No. 2 is chucked from a 1 in. length of 7/8 in. or 1 in. diam. brass rod. Again clutch plate thickness is 1/8 in. and the two shoulders ‘SS’ have a space between them of 7/32 in. Drill the 5/16 in. diam. end of shaft for a length of 4 in. at 7/32 in. diam. Chuck a 1 in. length of 4 in. brass

Above left, unit (right) the winch and rudder servos are housed in the port cabin with receiver and Deac supply beneath. The winch is in the starboard cabin. Sketches of winch with clutch details etc. appeared with the first article in the May issue. rod “C” and turn to fit inside hollow clutch shaft “A’’. An easy fit is required. Drill end to fit motor shaft and part off to 5/8 in. length. A light spring, 3/8 in. long, slightly under 7/32 in. diam. is made from fine gauge piano wire. File a V cross on each clutch plate face and finish with a small round file. Onto face of clutch No. | silver solder four short lengths at 1/16 in. diam. steel rod, for half its radius. These must marry into grooves at clutch No. 2 so the two faces meet. If necessary deepen the grooves to make an easy fit. The bearings are now made to dimensions, bearing No. 2 is made in two parts and bolted together with two 8BA bolts. Drill the 1/8 in. diam. hole at top whilst still bolted together. Finally separate the two halves to facilitate assembly. Assemble bearing No. 2 to shaft behind clutch plate No. 1. Attach shaft ““C’ to motor with epoxy resin, insert spring in hollow shaft, and place the bearing No. | in position, line up clutch shafts and fix bearing No. 3 first. Bearing No. 2 falls in place being already attached to the shaft. Any difference in height, either pack under or file off, until both clutch units are free to revolve. SELECTOR ARM & FORK The exploded view shows this in detail, with all the necessary measurements, and is made from 1/16 in. brass scrap, soft soldered to a length of 4 in. rod. The selector fork is silver soldered. The + in. rod is drilled through 6BA clearance. The brass plate is centre drilled and tapped 6BA. A long 6BA bolt attached this assembly to the base plate, allowing selector arm and fork to pivot. Pack with grease before assembly and solder the bottom of the 6BA screw where it breaks through the baseplate. Screw to base board in position indicated and attach to hull with odd blocks of balsa to form a platform onto which the base board assembly can be screwed. Drill a small hole in the cabin wall for servo rod exit CAPITAL SHIPS (continued from page 287) However, boats which can be seen on pre-World War II battleships can still be seen on 1971 Aircraft Carriers. I was content to press just the hulls without any details whatsoever and build up detail such as stem posts, keels and rubbing strakes, etc. later, in bits of plastic. I am always interested to know how other people tackle ladders and rails. Not so much the method of construction but the quantity of work required in any given method. I am not yet expert enough with my solder-pistol to use that method on so fine a and fit end of servo rod through hole in selector arm’ Retain it with a solderless nipple. The other end of servo control rod enters port cabin via a small hole, to be drilled and attached to engine servo arm. Two small holes are now drilled through cabin in line with centres at winch drums for line exits. These must be large enough for a small brass bead to pass through. I fitted +in. diam. brass tubes (short lengths) to these holes to prevent line wear and reduce friction. When the sails are fully taut, this small bead should contact the slot in selector arm. Make it from a small piece of 3/32in. diam. brass rod, drilled through to accept winch line and epoxied in place on line. With generous application of glue, when dry file a slight lead to each edge, it must be a sharp taper, otherwise the bead will wedge itself in the slot of selector arm. The 6 speed motor is on its second lowest speed. Sails are made from lightweight terylene (I chose red) and are hooked to the brass rigging wires. Rudder link for screw rod is 1/16 in. thick brass drilled at + in. centres and bolted to rudder port. The rod enters cabin through a small slot and connects to rudder servo. Insulate slot with soft rubber (greased). PAINTING Hulls Below waterline Hulls Waterline Hulls Above waterline Gunwale Name Cabin tops Hatch tops Decks Remainder of woodwork Red Black White Black Blue White White Clear varnish Clear Polyurethane Work as near as possible to drawings, and the model will be well balanced, no weights required. wire. I see from time to time how Admiralty builders go about it. On small scale models they have fine wire stanchions with the finer wire tacked on to it with small amounts of cement, the whole painted the colour of the stanchion, and then the horizontal rails painted black to represent the vinyl-covered wire rope. A small touch of silver every three or four stanchions represents the bottle screws. Ladders are made in the same way, although for 1/16 in. models Riko brass ladders would do fine. I hope these few tips will help the beginner who may come across some of the problems I did. 290

JULY 1972 ZONDA A new 60 in. I.0.a. freelance yacht by C. S. Gould P[\HE 1971 effort, Tornado, was quite a good boat to sail, tuning was and as confined she was quite docile the main to obtaining the optimum mast position and angle, depending which mast and sail plan was the order of the day. Once again the rudder area was increased, but this was expected as the rudder was the trim tab from Mistral. Its only fault, if you could call it that, was that it could not beat a Warlord — it came close, but could not hold a No. 1 Suit in wind that the 10 could. So it was back to the board again, and the think box said stability and lightish displacement, and so Zonda (another wind name) was born. Pointing the bows to the right, the lines were drawn out, but with no sweep on the starboard quarter for steering. The rocker was decreased from Tornado and was moved farther forward, the bow profile eased, more on the lines of Stormvégel, the chine angle was also flat- tened, more in the after body than forward, and with the displacement bug in mind a transom was decided on. This has enabled me to bring the rudder tube, the ever-faithful Bic pen case, back into the stern block, and still enable the crosshead enough room to operate and be adjusted; this was not possible on the pointed sterns. It was a fair job to carve to shape, and the final result is similar to a 1904 torpedo boat, if any readers have seen or modelled one of them they will know what I mean. The waterline beam of Tornado was retained, but the sides of the hull above the chine were reduced slightly in height and given a severe flareout to give a maximum beam on deck aft of midships of 13 in. Once again the new moulds were set up on the old building board and work started in September. 0.8 mm. ply was used for the complete hull and deck, suitably stiffened in the areas of the fin and mast, etc., $ in. X } in. ramin quartering for chine battens, and two laminations of } in. x 4 in. pine for the inner keel, as it is easier to bend over the moulds than one thick piece. Bow and stern blocks are yellow pine. After the fin and skeg were fitted and the hull removed from the board the chine battens and inner keel were gouged away in the interest of weight until it was deemed prudent to call a halt due to sei: strength factors. The fin and skeg are + in. thick Tufnol, and the fin was moved 2 in. farther aft than Tornado; with the rudder tube being carried in the stern block the rudder protrudes 14 in. The position of the fin and the C.B. have designated that this boat has a prognathous bulb, another point to be borne in mind when rounding the marks. Still with the weight problem foremost, the little aft hatch and coaming was done away with in favour of a circular plastic door pull, suitably doctored up to be watertight, the imitation windows and bars I usually put on the main hatch also got the treatment and were replaced by a painted club badge and boat’s name. Fittings on the deck are little different from a vane boat except one does not need the fittings for the spinnaker boom forehauls. In one of last year’s races I used a flattie attached to the mast, and with no forehaul, so that on the beat to windward it laid behind the mainsail, and with a little bit of rudder fiddling it blossomed out on the running leg, and it really made a marked difference. Although I was expecting the slack backstay to hang up on something, it never did. This boat is finished in white up to the chine, then a thin white line parallel to this, which is not a water line, and the upper hull is in purple with a gold coving line. The deck, as usual, is white, with the king plank brown, as are the deck edges. The deck planks came from the faithful laundry pen, and then one coat of Pu varnish. At the time of writing only one trial run has been made, and this in a light breeze indicated a fair turn of speed on the wind and reaching, but they all seem to sail fast when there is no opposition. She turned well, and the designed mast j = position appeared to be very near optimum with the mast and sails I was using, but whether the extra beam and the 1 in. deeper fin gives the little £ extra will have to be proved over a lot more and varied conditions as well as competition. The table of weights are: Hull complete 3 lb. 10 oz. Lead keel bulb 13 Ib. 4 oz. Rudder, radio, mast, sails, servo, fittings, etc. 3 lb. 2 oz. Total 20 Ib. Mast 284 in. from stem C.B. 14 in. aft of mast C.G. of boat 24 in. aft of C.B. C.L.R. 1} in. aft of C.G. 291

MODEL BOATS A simple non-self-tacking VANE GEAR suitable for Star-C or any 30-45 in. modern model yacht @EVERAL people have indicated that they are build- King the Star-C 42 in. one-design with no intention of fitting radio, but with the idea of sailing it with a simple vane-type steering gear. Some have asked for details of a suitable gear, and since the boat was designed as a dual-purpose model and sails well with vane gear, this ultra-simple one should enable them to spend many enjoyable hours sailing their models under good control. Most of the complications of a modern vane arise from the self-tacking function, which is an essential in competition. If the gear is non-self-tacking, it still works exactly the same except that it has to be reset by hand for each tack, a quite acceptable limitation for fun sailing. Self-tacking is only used on beating courses anyway, the vane being locked for runs and reaches. For those who like every detail, you can’t set a gye on a non-self-tacker; this is a spring or rubber band which puts the boat automatically on the other tack and is a useful racing manoeuvre. Again, it’s not necessary for joy sailing. This gear, then, is non-self-tacking, but it will steer your model accurately on any course you choose, provided the wind remains steady, the sails are correctly set and, of course, you’re not attempting the impossible of sailing into the eye of the wind. Item 1 is a strip of Perspex, Tufnol, plastic, or even aluminium 4 in. square. It is drilled to fit over a piece of x in. (max. o.d.) brass tube 2, then slit along from the hole with a fine saw so that a 6BA bolt and nut, 3, can be tightened to clamp the bar to the tube to make a friction fit. At the rear, a wider slit is made to accept the foot of the vane, 4, which can be retained by two 8BA bolts, 5. Another hole is drilled at the fore end to accept a 6BA bolt which clamps in place washers or lead discs etc., to provide a balance weight (6). A fine hole towards the rear takes a fine wire, 7, to provide a pointer reading against the scale 8. | I | I ‘ \ oth eB Q reser a a =|, —S a: 6 SLIT THROUGH tier 2.1/2″ PLUG APPROX. aa “1 Pa © 3/16” O.D, \ \ —=| [*—SHAKE-FREE FIT IN 2 10 DISC TO SCREW TO DECK L Doe 2 7 Parts shown full-size (except sketch) mi| 296

SUEY The whole mechanism should swing freely on pintle 10 and by tipping the boat the balance weight 6 can be adjusted to balance the feather, which for a Star-C will probably need to be about 9 x 23 in. cut The scale is a disc of Formica or some form of stiff sheet plastic graduated in degrees; two small. school protractors glued together, or a small 360 deg. protractor, would be suitable. It is epoxied to the tube 2, after attachment of arm 9 if desired. This arm is 22g brass or similar and should for preference be silver soldered to the tube; epoxy may be adequate. The forward end is slotted and the after end extends just far enough to carry a hole which is an anchorage point for a very light rubber or spring centring line. Tube 2 needs now to be blocked at the top; an alternative to the tube would be a piece of 75 in. rod accurately drilled not quite through. The blocking piece should be countersunk with a drill point to form a bearing for the point of the pintle, 10, which is an accurately tapered piece of rod fitting snugly but without friction inside tube 2. The rod is silver soldered into a pintle plate, which is simply a disc to screw to the deck. Make sure that it is truly vertical. The rudder tiller 11 is fitted to the top of the rudder stock and should be slotted (it could of course be a narrow U of wire). A bolt 12 is fitted through 19:72 from fairly hard s+ in. balsa and given a couple of coats of banana oil. If you wish, check with the boat afloat, as on heeling the buoyancy of the rudder affects the balance slightly. Install on a Star-C with the pintle 1} in. forward from the transom. This will probably prevent use of the rear hole in arm 9 for a centring spring, but a length of shirring elastic hooked to the bolt engaging the tiller and carried forward will be equally suitable. If a backstay is fitted to your model, this should be split about 18 in. up and the two ends hooked to eyes in the deck edge, far enough forward to clear the vane. the slot in arm 9 and nutted beneath, of such a length as to engage fully through the tiller slot. This bolt could be through a simple hole in 9 into the tiller slot, but having both items slotted allows the bolt to be adjusted fore and aft, thus varying the linkage ratio, i.e. the amount of movement of the rudder in relation to the amount of vane movement. Although for fun sailing this is not terribly important, it is instructive to try different settings. To use, briefly, point the boat on the desired course and swing arm | round until the feather is aligned to the wind. It isn’t guite as simple as that, because the wind of the boat’s motion must be taken into account and what strikes the feather is the apparent wind, a combination of true wind and the boat’s own speed. The difference can be several degrees, but the simplest way to accustom yourself to allowing for it is to experiment. Learning to use the vane can add point to your sailing and make it more enjoyable. For readers wanting to go further into this fascinating subject, we recommend the M.A.P. booklet No. 1., Vane Steering Gears, price 30p. inc. post from our offices. NON-STICK Readers Write… Dear Sir, A wallet of chrome-vanadium spanners in the small B.A. sizes is sent It’s always been a problem when knocking up a small amount of glass resin, of what to mix up in and then to writers of letters offering something new or interesting to say. Well, first of all, Dear Sir, Being a keen supporter of Model Boating | feel that recent developments which have brought Multi Boat Racing to the fore should receive a little more organisation in order to get the best out of the sport. As one is always ‘COMPETING’ it is rather difficult to compare performances, say with people in other parts of the country or even with people in other countries, and | feel a standard of performance should be evolved, concerning the duration and speed of the com- petitor. Such as a_ simple formula Distance x Time. Some people will argue that some courses are quicker than others (say Maidstone and Hove, two totally different courses). However, as most of us race on most of these courses during the year, a performance standard would _ probably equal itself out. The only snag is that organisers will have to prepare them- at the same time will breed a standard—one always drives. higher better against a good competitor than a bad one. | feel, however, that equally competitors not taking part would thoroughly relish the (rare) sight of 6 boats racing together for probably the whole of the race. Finally, the course. Mostly clubs have followed the ‘M’ type course. This is useless on a large course as it means a straight drive round. The course should always’ involve a_ chicane (tightish) of some sort in order to promote better driving and boats that really are good under all conditions. | have seen Naviga speed boats in large Multi races which in fact are very poor all round boats and would never survive my own club’s course at Tanhouse which is as follows: 12) fe) selves to be able to measure the dis- tance round the course— it could be done thus: Example at Hove course might be as follows: 400 yards course x 10 laps 20 minutes =EFFICIENCY FACTOR OF 200 One would also suggest races of less than 20 minutes do not qualify as a multi race. | personally find quite a difference in boat requirements for 10minute races and 30-minute or 1-hour races. A further point | would like to see, for which | have found a lot of support, is for the organisers to have a final race of the day for the top 6 competitors (frequencies permitting). Whether competing or watching | think fe) @) fo) e) e) ooo00 Drivers A final point which has been made to me by other competitors is that a Multi race must involve at least one pit stop to take on fuel (say a minimum of + pint). This would again prove the competitor’s all round efficiency and that of his mechanic. Twickenham John Stidwell 297 how to clean out the brush afterwards. | packed up using a ful from chemists, and consist of a cotton wool pad wound. on t0 eBch.end of a stick about three inches long. And to mix up, | use the aluminium tray from a steak pie. When the mixture hardens off, just bend the tray around from and the the Nazeing. resin aluminium, clean for reuse. cracks leaving the away tray M. Evans BONES Dear Sirs, Mr. P. N. Thomas’ closing remark to his fine description of the cross-channel steamer Brighton (page 198, May 1972 issue) raises an interesting and possibly somewhat neglected point of scale ship modelling: just how to that ‘bone’ in her teeth! put It is common observation that the flow over the ship’s bows follows a characteristically curved pattern, The height, contour, location, and appearance of the bow wave crest is known to depend as much on speed, form and proportions of the hull as on the shape of the entrance. The readers conversant with fluid dynamics will also recall that any flow entering the leading edge of a foil under an angle other than 90 deg. is actually turned from its- head-on path to sweep across the foil in an arc. This particular flow pattern is commonly termed ‘Schlicht- ing waves’ and was first observed by a German aerodynamicist. Accordingly, a sharp raked stem is bound to throw up a higher-arched bow wave crest in the form of a ‘sheet’ of strongly-aerated