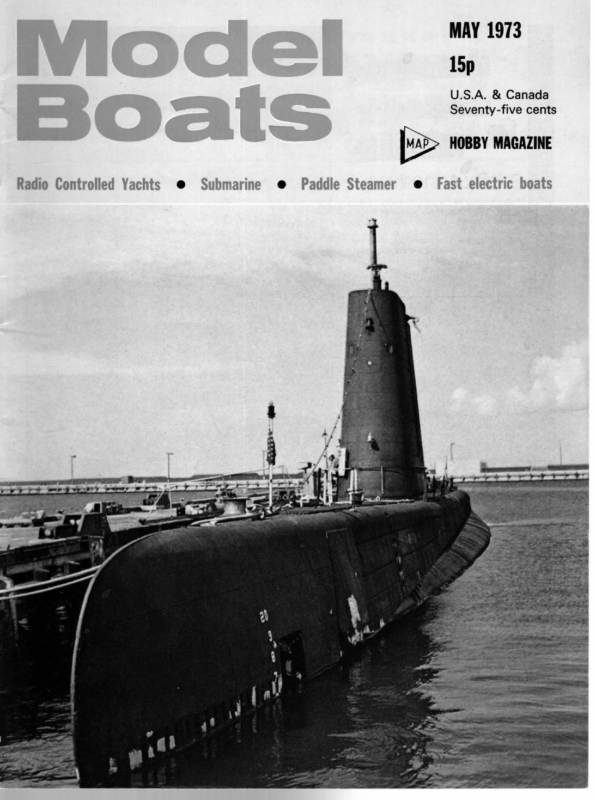

MAY 1973 15p aTT U.S.A. & Canada Seventy-five cents mt Radio Controlled Yachts @ BS Submarine a @ HOBBY MAGAZINE Paddle Steamer oe Fast electric boats

MODEL BOATS Canadian R/C Yachts John G. Ball recounts some of the findings of Metro Marine Modellers of Toronto in this fastest-growing sport JETRO MARINE MODELLERS have acquired drums are on one shaft and so the drum diameters match the ratio of the boom to jib. Some boats have limit switches built on their gearbox at the full in and full out positions. The micro-switches for the motor a new operating site, possibly one of the finest regatta sites in the world. Ontario Place, on Lake Ontario, just minutes from the heart of downtown Toronto, is the waterfront showpl ace of Ontario. With its Marina, restaurants, shops and play-ground, it offers a wide facilities. southern theatres, variety of are mounted right on the servo. Most of the boats are using proportional radio which is a tremendo us improvement over the tuned reed radio. As weight is an important factor, especially in 10r boats, we are always attempting new ideas to simplify the winch. The sail and power boats operat e in the ‘Haida Basin’ (Tribal Class destroyer HMCS Haida, cf. Model Boats July 1967). The scale division operates on the ‘Reflecting Pond’, a large circula r pond some 15 in. deep overlooked by restaurants, and sheltered from the strong breeze off Lake Ontario grassy banks. The latest idea in this area was to remove the feedback potentiometer from a proportional servo. The rotary by high meter. 15 m.p.h. freshening to 25 m.p.h. by lunch time. The club has almost 30 R/C 10-raters and for our first season of Marbleheads, 5 boats already in the line. up from a wood planked hull), two Warlords, two Impalas, two Crackers, a Marie III, and one Stroller. We have made a few discoveries in the past three years of R/C sailing, which may be of interest. Firstly, the 60 in. waterline is a bit long for R/C do not carry a spinnaker and so the to the This pot was then connected back to the To The first solution would appear easier, but you can build as lightly as possible and after allowing We had to lower the aspect ratio slightly, to help the boat when it is running. Bill Barker’s white-hulled Warlord with its very low aspect sail is untouchable when the wind is 25 m.p.h. or better. We have also modified the skeg and rudder on some boats. At first the skeg area was reduced and the rudder blade enlarged, but now we are using a spade rudder (counterbalanced with no skeg at all), which is even better. We are using winches to control the sails. These are made up from a small worm gear driven by an electric motor (Monoperm is ample), and ratios of 100:1 up to 200:1 seem average, with full out to full in taking 7 to 9 seconds. The two directly performance may well suffer (ignoring the designer’s cries of woe). The second alternative then would seem safer, but how to reduce weight on a finished boat? File off some lead? Drill a couple of holes in the lead? Neither alternative seems desirable. So start from the ground up. Build a boat. This way Warlords are lacking in sail area on a broad reach or arun. connected bring a converted 10r back to rating requires either 1) reduce sail area on increased waterline, or 2) reduce overall weight to return to designed water- The 10-rater fleet is made up from 23 Red Herrings (a club project, 22 glass-fibre hulls off a mould made We then was not allowed for in the original construction. water, including a very fast White Rabbit and eight boats on the way, all to the Bambi design. 10rs. was circuit board of the servo. The result is a proportional winch with the saving in weight of the winch gear, drive motor and batteries! Still on the subject of weight, we have the impression that many R/C yachts in England are converted vene boats. We do not think that this is good practice, because the weight of radio, batteries, etc. The sail regatta at which these photog raphs were taken was the first regatta of last year in the Club’s ‘Fred Mathews Trophy’ series. The day was windy, starting out with output drums and then into a ten turn miniature potentio- for the weight of radio gear, cast the keel accordingly. Even consider deepening the keel a little to stiffen up the boat to compensate. We can build a 17 |b. Marblehead, add radio, etc., and still have a 12 Ib. keel. So THINK LIGHT, and build! Sails deserve some attention, as the requirements of vane sailing and R/C sailing differ considerably. In vane sailing, the boat is started on one tack and (usually) at the end of the tack is turned manually. The rudder serves only to keep the boat at a . constant angle to the wind. An R/C sailboat must be able to tack freely by use of the rudder and, in 188 addition, round buoys, and manceuvre to avoid other

MAY 1973 Opposite, racing in the Haida basin; the two boats near the ship are full-size dinghies. Right, winch gear from scrap in writer’s boat Roller bearing shaft, 14in.-wormwheel. boats (as many as six or seven in a heat). The trend in modern vane sailboat designs, such as Cracker, seems to be towards large jibs, and proportionally smaller mainsails. Ratios of 50% area distribution between main and jib seem to be increasingly common. This trend does not lend itself to R/C sailing, because the power generated by the jib makes it very difficult to tack, as the boat cannot luff and keeps falling off. We find that the best area distribution of jib to main is normally about 35% to 65%. Most of our masts to date are built up from two pieces of sitka spruce with a sandwich of +s th ply- wood. Each piece of spruce is pre-grooved on its trailing edge with a half round groove and when the three pieces of wood are brought together, the channel MAST CONSTRUCTION i” 16 iene 1 \PLANE AND SAND TO AIRFOIL SECTION fx 1″x 86″ SITKA SPRUCE created takes the corded luff of the main sail (see sketch). For the coming season, a number of boats will be sporting 3 in. diameter aluminium tube masts with double luff main sails. This article has been prompted in part by the possibility of an international regatta in England in 1974. We have been informed that there may not be sufficient numbers of R/C sailboats in England to justify the trip, but we would love to come and sail against you in friendly competition in 1974, and hope that between now and next year there will be an English fleet formed. If there is anyone who would like to enter into correspondence regarding R/C sailing we will be happy to respond, to exchange ideas and develop the hobby/sport of R/C sailing. (c/o 50 Benlight Crescent, Scarborough, Ontario, Canada.) First around the buoy is Ray Davidson’s Red Herring, closely followed by Bill careers Warlord, and the writer’s mpala. WIRING DIAGRAM FOR WINCH MOTOR L—— MICRO SWITCHES OPERATED BY SERVO C=COMMON NO= NORMALLY OPEN N0.= NORMALLY CLOSED 189 WORM GEAR WINCH ORUM (PLAN) a WORM GEAR UNIVERSAL COUPLING 70 BATTERY MO.7OR =f MICRO SWITCHES T i 7 SERVO 70 RECEIVER

MAY 1973 GOSLING A new, simple 36 in. Restricted class yacht for vane sailing or lightweight radio control By VIC SMEED LTHOUGH some people feel that the 50-in. Marble- head is the best size yacht to build for competition, to a beginner it seems an awful lot of yacht; many beginners think in terms of something a couple of feet long to start with. Such people may be tempted to go as far as 36 in., if a simple and inexpensive design is available, and if this is successful, then it’s no great step to a Marblehead. This is what this design is all about. The 36-in. Restricted class is actually fairly free of restrictions — basically, the hull, etc., has to fit in a box of internal dimensions 36 x 11 x 9 in. and the total weight must not exceed 12 lb. There are no limits on sail area, etc., and only one or two minor prohibitions which need not concern us here. The class is recognised for radio control. In common with most aspects of yachting, the 36 class is positively booming at the moment, with all sorts of people having a go at one, from top skippers to club juniors, and there are some pretty varied approaches, too. At one time, model yachts tended to get bigger and heavier all the time; in the case of a 36, this meant that it was unthinkable to build at more than an ounce or two under the 12 Ib. allowed. However, recently we have seen very light A boats doing extremely well, 10-raters coming down from around 35 to 25 Ib., and Marbleheads from 21-23 Ib. down to 16-18 Ib. and less. Most of these boats change’ to smaller suits of sails when the wind pipes up, sooner than the heavier boats, but they still hold their own and, in fact, stronger winds favour lighter-weight boats. In very light wind the heavies sometimes prove superior, but most yachtsmen can remember occasions when some cheeky little lightweight kept ghosting along when everything else was becalmed. Applying the lightweight philosophy to the 36R suggests a boat of only 8-9 Ib., so this was the first design parameter. For ease and cheapness, a chine boat seemed return for the ease and speed of casting. A simple boat needs a minimum of fittings, and it would be hard to get many fewer than shown for this model. If you have some scrap lead, total materials should cost less than £3, less sails and paint, the most costly item being the ply for the hull skin and decks. If cash is a problem, the sheets of veneer used as packing round crates of ply are usually free at timber yards; this might need extra stiffeners between bulkheads and it would be necessary to keep an eye on total beam (not to exceed 9 in.) and total depth (not to exceed 11 in.) as it is usually about 1/16 in. thick against the 1/32 in. allowed for on the drawing. Hull An unusual method of construction is used which greatly simplifies building. The hull is made in two halves, split on the centre line, and the side skins are fitted before lifting the halves off the board. First trace and cut B1-B6, two of each, and check each pair for symmetry. Trace the mainframe, or cut this part off the plan, and tape or pin on a flat building board. The flatness of the board is important. We used a piece of dry ? in. blockboard and checked its truth at each stage. The top and bottom members of the frame are } x # in. spruce, edge on. Since the fin and skeg are each + in. thick, cut 4-in. rebates at the correct positions before pinning the bottom member in place. Position both strips obvious and experience suggested that a 36-in. hull, with fin and fittings, could easily be built for 2 1b. maximum, so allowing half a pound or so for rig and two or three ounces for a vane, we could reasonably have 6 lb. of lead, i.e. some two-thirds of the total displacement as ballast. Carrying this as a bulb and keeping a shallowish hull made the 11 in. maximum permissible depth look quite reasonable in preliminary sketches; most 36s look as though they are cramped for draught. When designing to a restricted draught it obviously pays to use the full allowance and to get the lead as low as possible. This means a bulb, which means casting, but we can sidestep the pattern/mould stages by simply cutting the bulb profile twice in a sheet of 3-in. blockboard, melting the lead (discussed last month) and pouring into the two sawn holes, after nailing on a backing board, of course. The resultant pieces, screwed to the fin, offer a streamlined shape to the waterflow in forward motion and can have very little ill-effect when the boat is making leeway, i.e. crabbing slightly; there will be a little eddymaking on the low pressure side, but this is acceptable in 195 Top, the first hull half is completed and the second under way; note slots for fin and skeg. Above, applying the side skin with clothes peg ante and, below, joining the two ull halves.

1 ! 1 1 ! 1 over the drawing, tapping in 1-in. panel pins to locate them exactly in place. Glue one set of B1-B6 accurately in position using a small square or true block to ensure uprightness and using Durofix or epoxy or even Britfix cement as an adhesive. Leave to dry thoroughly. Note that the bottom member will be fractionally short of the full hull length at the bow, because of the curve. When dry, cement the 4-in. sq. balsa inwale and chine stringers in the notches in the bulkheads, shaving the fore ends to fit snugly against the spruce members; see plan view of bow as a guide. Check that these sit neatly in the notches, using temporary pins, Fill the bow space forward of B1 with laminations of 4-in. balsa and when dry, pare and sand to a fair surface to receive the side skin. This means chiselling away to taper the spruce parts. Sand all the hull side to ensure the skin seating, then cut a piece of brown paper slightly larger all round, lay in place and press all round the edges to make a crease. Cut to the crease line and check that the paper then fits accurately. When satisfied, use the paper to mark out the ply panel, allowing 1/16 in. or so trimming overlap all round. Do not discard the paper template. Ply, 1/32 in. thick, can be rough cut with scissors and then trimmed down to the drawn line with either a sharp knife or the scissors again. Lay the panel in place on the hull and push a pin through into B6. Check that the panel fits. Remove, leaving the pin in the ply, run cement all over the contacting surfaces of the frame, relocate the pin and smooth the panel down, holding with clothes pegs and/or pins. Leave to dry really thoroughly. When dry, this half can be lifted and the panel pins eased out with pliers. Turn the drawing over and replace The drawing above gives an indication of the completed plan which has lots of instructional notes and further sketches. Fullsize copies are available, Plan MM 1164, price 65p including postage and V.A.T. from MM Plans Service, P.O. Box 35, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1EE. Right, fitting the first bottom skin. 196 the panel pins through the same holes in the paper. This ensures that the second half will match the first exactly. Follow the same procedure, except that you are, of course, making a mirror image of the first half. Use the same paper template for the side panel, thus checking symmetry. When the second half is dry, lift and — great moment! ~— mate it with the first. It should be spot on. The halves can be glued together, using bulldog clips or G-cramps or strong rubber tied round the spruce bits. If there is a tiny discrepancy, make the straight (deck) pieces flush and deal with the discrepancy in the next stage. You may like to run a fillet of glue round inside the stringers at this point. Again, when dry, trim away any excess ply from the deck edge and sand smooth and flush with the bulkheads. It pays to take a pair of compasses and mark at each bulkhead the depth of the hull side, from the top edge, taken from the B1-B6 drawings; this is because part of the chine stringer has to be trimmed away with the ply and if the marked points are connected with a pencil line, you have an exterior guide. Trim this excess and bevel the spruce centre members with a sharp knife or chisel to form a fair seating flush with the bulkheads to receive the bottom skins. This is where you can lose any small discrepancy in levels; pare down till the centre joint line is the highest point. Use the brown paper template idea to establish the shape of each half bottom skin, but this time we need an accurate butt joint all the way along the centre line. Cut the first ply panel and pin in place to get the joint line just right, but before fixing, fit the fin and skeg. Both these parts slide through the slots previously cut and

MAY 1973 butt against the upper mainframe, a scrap of, say, 3/16 in. sq. being glued each side for reinforcement. The fin must be stiff and warp-free and is, therefore, laminated, using a 1/16-in. ply core faced with 3/32-in. obeche each side. It is just possible, by piecing, to get both sides out of one 4 in. wide sheet of obeche, but some builders may prefer to buy two 3-in. sheets, which would enable them to build the skeg and rudder in the same way. Otherwise, these items can be made from two laminations of } in. spruce or obeche, etc., with the grains at a slight angle to help warp-resistance. We tend to favour Durofix, used as the maker recommends, for these items: the adhesive needs to be reasonably waterproof. Leave them under weights on a flat surface to dry out, then carve or plane and sand to section. For the curves on the fin, glasspaper wrapped round a stub of thick dowel or even a small, round bottle will ease sanding and the ply core makes it easier to see how the sanding is progressing. Epoxy the fin and skeg in place, then take the pre-cut bottom skin and cut away to clear them. Cement and pin the skin in place, then follow with the other half. Trim and sand excess carefully along the chine and transom, then cover B6 with a piece of 1/32-in. ply. We fitted the skins on before finally fixing the fin and skeg, but though there were no problems, were we doing it again we would fix them first. Incidentally, before completing the bottom skin, you can check that the depth from the deck line to the bottom of the fin is under the 11 in. allowed by simply using a ruler and allowing for deck thickness. Drill carefully through the mainframe top and bottom, flush with the skeg after edge, a shade small for the +-in. rudder tube and file out with a rat-tail to make the tube a snug fit. The rudder pivot rod (or tube) is 4-in. diameter, ie., a rattling fit in the 4-in. tube, and it is desirable to avoid much of a gap between the skeg and this rod, which forms the fore-edge of the rudder, as far as possible. Also drill a drain hole through the transom; ours was lined with a scrap of tube epoxied in. It is amazing how water can find a way into even a ‘sealed’ hull of this type and with a drain it takes only a moment to up-end the hull to clear any water. The centres of B2-B5 can now be cut out, a Humbrol Multicraft midget saw being excellent for this. The glasspaper-wrapped dowel or bottle enables the cut-outs to be cleaned up neatly. Sand the exterior of the bow to shape, then lay the hull upside down on the remaining ply and carefully pencil round it to mark out the deck. Cut out, pin with a pin fore and aft, and trim to final shape. These pins will be replaced in the same holes when the deck is glued on. Mark positions of blocks on underside of deck and glue blocks in place. The hull interior and deck underside can now be thoroughly varnished at least two coats to prevent water absorption. Clear polyurethane does this job very efficiently and with minimum weight; small amounts can be bought in Woolworths. At this stage our hull and deck surprised us by weighing 214 oz., well inside the target weight. (To be continued Above, the hull to the stage covered in these notes. Below, interior views of the fin and skeg fixing; sheet on the fin for economy and fillet strips visible in both views. SCOTTISH M.Y.A. The Scottish M.Y.A. 1973 events are as follows: 19 May 6 Metre 20 May 2 June 10 June Championship Championship 17 June Scott Trophy 1 July Legget Trophy 18/19 Aug. Wade Cup Greenock REGATTAS 2 Sept. Knightswood Open M Silver Wing Trophy Paisley Tannahill Trophy M Class Team Paisley Open M — Open M Paisley Open M Paisley S.M.Y.A. v. Northern District 197 note piecing of side A Class Championship 9 Sept. Olympic Trophy 15/16 Sept. M Class Championship 22/23 Sept. Bonar Cup Greenock —_ Knightswood Open M Leith & Dist. Edinburgh Fleetwood —_ M Class International 7 Oct. Marshall Trophy Paisley Open M 13/14 Oct. Henderson Trophy Queens Park Open M British M.Y.A, competitors would be most welcome at any of the Open races.

MODEL BOATS R/C Yachting Official recognition of several classes is the breakthrough we have been waiting for, says Bob Jeffries AFTER SO Many years as a minority interest, the sport of radio controlled yachting seems at last to be coming into favour, and with the Model Yachting Association now at last taking a serious interest, it would appear that 1973 can be recorded up for our smaller performance. as the year that really saw the recognition of this branch of our hobby. I think the statement in the latest issue of the M.Y.A. Newsletter, I quote ‘The M.Y.A. is now taking an active part in what seems to be a rapid development of R/C yachting’, is the best news yet. It is now up to clubs and officials of that august body to put into practice their good intentions. They have made a good start by their recognition of further classes in this branch of model yachting. I am firmly of the opinion the reason for our sluggish start has been the fact that only the ‘Q’ class was recognised. Fine though the performance may be, the sheer size frightened too many off. Now we have a reversal of the position. The M.Y.A. now recognise a total of five classes for R/C sailing; these are the 36R, the ‘M’, the 6m, the 10R, and the existing ‘Q’ class known now as, respectively, the R36 in. R, RM, R6m, RIOR, and RA classes. A big step in the right direction, but I feel the sudden recognition of so many sizes will leave the potential R/C yachtsman with a dilemma as to which size to settle on. I have studied the American scene as far as R/C yachting is concerned and from journals I have read, and the many correspondents I have in that part of the world, it is obvious that radio yachting there is now in a very big way. One kit manufacturer has already sold over 600 kits selling at around £250 a time, and that without radio, so it is obvious we have a long way to go to catch them up. I am confident our model yacht designers and manufacturers of equipment are every bit as good, and it is just up to individual enthusiasm for us to make Considering these new classes, I feel the 36R is a bit too small for serious competition sailing, and the 10R, although lighter than the ‘Q’, is still a big boat to transport. I have enjoyed many years as an R/C Skipper on ‘Q’ class originally, but for the past three years have concentrated my interest on the ‘M’ under radio control. I have found this size can give every satisfaction, and with the light radio equipment numbers now available, by and the a superiority many in excellent designs available for this size through the M.A.P. plans service, I feel it is the ultimate size that will gain international popularity. seen in America, where this class. This is already being is the fastest growing I hope these comments will steer the budding yachtsman into this ‘M’ class, unless there are very good reasons for considerations for others. How does one start? Well, there are three ways. One can buy a secondhand boat, not necessarily a championship design; I have known of many boats with an indifferent performance when sailed under vane control which have turned out to be really first class performers under radio control. One can buy a new one from either Germany or the U.S.A. (these will cost around £150 to £200 before fitting radio) or one can make one from one of the wide range of designs published by M.A.P. I started in sailing ‘M’ class by buying a very elderly Tucker design from the local club. I originally fitted it with home made analogue radio gear, and had a lot of fun sailing it. I later stripped it down, and rebuilt it, and fitted it with modern digital equipment, and I have recently disposed of it to a 204

MAY fellow local club member, considerable success. who is sailing it with For my next boat, I decided to make my own, and after a study of designs available, I chose Priest’s Bewitched as being, in my opinion, the design most likely to prove successful as a radio boat. I was fortunate, as at that time we had a new member in the local club who was a bit of an expert as far as glass fibre was concerned, and I persuaded him to make to this design. He spent a lot of time making a really accurate wooden plug and finished it to a really high gloss finish. The mould proper was made in two halves in glass fibre, and following the hard work that had been put into polishing the plug, the mould had a high gloss, which resulted in the finished colour, hulls, which required, further finishing. had being been moulded satisfactory I was fortunate in in without the any being able to have one of the first hulls, and it did not take me long to complete it. The design was exactly to the Bewitched drawings, except that I made one fundamental change. The original design was of course intended for ‘free sailing’ under vane control, and the rudder was only required to hold the boat on its prescribed course. Under radio control, we need a manceuvrable boat, and I fitted a spade rudder. This was successful beyond my hopes, and without exception all other yachts in the local club have been so adapted. They say imitation is the best form of flattery, I claim no originality for using this type of rudder. I first saw it on a most successful German design, and copied it from that. This boat, which I called Electra VIII, was sailed for the 1972 season, and I was well pleased with its performance. I am of the firm opinion that however good the design or performance, there is scope for improvement. In the striving to improve lies the fun of our hobby. As the season progressed, I decided to build yet another boat, keeping the basic Bewitched lines, but modifying the hull to use a bulb keel in place of the fin on the original design. This meant a new mould, as the original mould had the garboard 1973 radius moulded in, and now ‘M’ class rules do not insist on this feature. The original wooden plug was modified, and a new glass fibre mould made. | kept the keel weight the same, but as it was now in bulb formation, I increased the draught, by fitting it about 14 in. lower, and by so doing obtained a really worthwhile improvement in the righting moment, which will stand me in good stead when I fit the higher aspect rig I want. My improved version (in my opinion) of Bewitched, now called Electra 1X, is now sailing, and only time will tell if the alterations were worthwhile. The new boat is slightly heavier, but still about half a pound under the designed weight of 234 Ibs. It still has the spade type rudder, but I have in this instance moved the whole rudder about 1 in. further forward, which enables the rudder to work in deeper water. On the original design, the top of the rudder was on the static waterline, and when running downwind in a fresh breeze, it was possible to see the top of the rudder above the water. I had this latest hull moulded in light green colour, and was fortunate in being able to buy an off-cut of thin Formica of exactly the same shade for the deck. As both hull and deck are self colour, no painting or maintenance is required. The fin is in waterproof mahogany marine ply, and is painted to match the hull. Originally the mast, sails and rigging were trans- ferred from the earlier boat, but now a completely new set of fittings have been made to enable me to fit sails of a very much higher aspect ratio. A few details of this new rig may be of interest. On earlier ‘Q’ boats, I had used a radial jib boom, and following the satisfaction I found with this design I decided to incorporate it in the new boat. I could publish drawings and dimensions, but I feel a good photograph is worth a lot more, and the dimensions would probably be different if used on a different design anyway. The mast was of 4 in. diameter aluminium, and as it was of rather thin wall, it was somewhat springy, Heading picture shows the swing lever sail mechanism and_ tube rudder link, Left is a view taking in all the deck fittings including the radial fittings for both jib and = main booms. Note the elevated tripod sheet guides and _— general sturdy construction. 205

MODEL BOATS Top picture shows sheeting arm, etc., from the side; note drain holes in hull side. Bulb fin and spade rudder are illustrated below. and liable to bend with the strain of the upward pull on the main boom in windy conditions, so I decided to make a similar design of radial boom fitting for the mainsail as well. Again dimensions could be given, but the photograph will give sufficient information for anyone who thinks the scheme worth copying. This takes all the strain off the mast, and enables the sails to be set, and to keep their set in almost all conditions. After much experimenting, I was able to find the best position for the mast on the original design, but realised these figures would probably not hold for the new boat due to the change in underwater design, and differing balance. Brackets were therefore made to enable nearly 4 in. of fore and aft adjustment on both mast and jib boom. The whole rig can be removed and replaced in a different setting in a matter of minutes at the pondside. Two points on the rigging are worth mention. It is usual to use stainless steel wire for the rigging, and I have used the stranded stainless steel wire, Nylon covered, which is available from most fishing or anglers’ supply shops. This is available in various strengths. I use around 72 to 90 lb. breaking strain for the main shrouds, and the somewhat lighter 35 lb. for forestay, backstay etc. This wire lies flat and does not coil up like the solid wire. The packets come complete with small thimbles to form the loops at the ends. Most shops selling this wire have the special tool for forming these ends. I personally have never bothered to borrow such tools, and make a perfectly satisfactory finish with a somewhat blunt pair of side cutters, just taking care that the joint is crimped and noi chopped in half. The other point concerning rigging, I no longer use turnbuckles for tensioning the rigging. The sketch (Fig. 1) shows how the mast can be jacked up. The scheme is io fit all sheets and shrouds with hooks, and after fitting just screw up the mast until all are in suitable tension. All very simple, and most effective. The big advantage is when the correct setting has been found, it is easy to reassemble to that setting on wm MAST pie wire HOLE 4″ WHITWORTH THREAD : “BRACKET TO ALLOW ADJUSTMENT OF MAST N FORE & AFT DIRECTION every visit to the pondside. (To be continued) S.S. UGANDA Well-known ‘school ship’ at 100 ft.-1 in. ren feat: S.S. Uganda was built in 1952 for the British India service between London and East Africa via the Suez Canal. Accommodation was provided for 166 First Class and 133 Tourist Class passengers. In addition the Uganda carried nearly 10,000 tons of general cargo. The granting of independence to the African countries led to a gradual fall off in the demand for passages and in 1968 the Uganda was sent to Germany to be converted into a cruise and school ship. The alterations and additions carried out were extensive, being in particular concerned with the conversion of the ‘tween decks into accommodation for students; together cinema. with The in all 34 dormitories classrooms, First Class were provided, lecture rooms and a public rooms remained basically unaltered, but additional cabins were built into a new house at the fore end of the extended super-structure. The Uganda re-entered service with. accommodation for 920 students and about 300 Cabin 206 Class passengers. Outwardly many alterations had been made including the removal of all cargo handling gear. The two original pole masts were also taken out and a signal mast and a small stump mast to handle the stores derricks substituted. Six additional lifeboats and launches were provided. With the Nevasa, the Uganda provides an unusual, possibly unique, shipping service. The activities of these two vessels as school ships are well known, in fact many of our younger readers may have travelled in either of them or in one of their predecessors. What is not so well known is that the adult passengers travel in delightful modern accommodation quite independently of the school children although they are able to share some of the facilities if they so wish. Cruise ships generally now limit the number of passengers carried. This is very much the case with the Uganda and although she was not built specifically for cruising she can also offer facilities, service and space which compare more than favourably with many other ships offering cruises for adults alone.