$1-25 M.E. Exhibition report oe Tropicaltug e 1975 power regattas HOBBY MAGAZINE

MARCH 1975 The R/C Revolution in Model Yachting Larry Goodrich, Trustee, Central Park M.Y.C., U.S.A., with Niel Goodrich comment on the model yachting scene as they see it. URIOUS that one who gets his ideas into print is automatically considered an expert, but that was the assumption of the many fine letters I received in response to my first article (March-May and July, 1974). Not to disillusion anyone, I dutifully tried to answer all the letters as best I could, in many cases trying to suggest solutions to some pretty baffling problems. [even dabbled | in analysing hull trim and sail cut from photos sent by two enterprising (apparently the only two) R/C skippers in Rhodesia. In responding to those inquiries I was forced to think through my experience and to formulate my ideas in more systematic concepts, and, in return, my correspondents have provided me with a great deal of information about what R/C skippers are doing and thinking in various parts of the world. My 16- year-old son, Niel, and I have just concluded another R/C racing season with reasonable success, from which we have learned a great deal. Soin the absence of better authority, and as a way to write to all my correspondents at one time. I am back again with some more comments about R/C model yachting. The R/C Revolution. It is now clear to me that R/C will displace vane in a few years and that ultimately vane will become to R/C what squash is to modern tennis. To my vane friends who just cannot seem to accept this, I try to point out that I did not will it this way but it is a fact we had all better get used to.* In each country, the R/C revolution will spread as and when the price of the R/C equipment comes down to a reasonable level and skippers get a chance to try it. (Central Park members can now buy a two-channel Futaba set for $90 in New York City, but I am told it would cost more like $240 in England.) A weekend of fluky winds, when the R/C skippers can continue to have fun racing while the vane skippers struggle around the shore, may be all the members of the local club need to convince them of the wonders of R/C. Peaceful Revolution. Dyed-in-the-wool vane skippers need have no fear for, with goodwill all around, the revolution should be peaceful and the sport will certainly be better for it. Implicit in my analogy to tennis is the idea that model yachting will be much more popular than ever before, while vane will become an art admired, if not practised, by most of the R/C skippers. To the older vane sailor, R/C may seem like a whole new sport with its Olympic courses, racing rules and tactics and all that mechanical junk on board. But he already knows what makes a hull go and how to read the wind and set his sails to it, and R/C simply allows him for the first time to steer his boat and control the sails all the time. Sure, there is a lot new to learn, but a great many vane sailors have made the switch and are enjoying the sport much more. There are also many new and interesting people in the sport. Dinghy racers find it very challenging and relatively easy to pick up, and we have some refugees from R/C aircraft modelling (a crash destroying a $400 plane makes a ready convert); and, of course, many powerboat enthusiasts have found sailing more challenging. Rounding marks can be quite tricky. First yacht is forced deep and wide by second, and second and third try to cut inside, hoping for safe leeward positions on next leg. Lower picture shows countermoves; first boat has established windward position, blanketing second, and is trying to drop off slightly to gain speéd* to prevent other two getting ahead. Turbulence suggests sharp turns, slowing boats considerably. First boat maintains speed but losses distance for following long sweeping arc. Manoeuvrability, acceleration, and tactics all important in such circumstances. Designs for R/C. One of the main problems in getting started in R/C is the sad fact that our marvellous vane designers have not yet (January 1975) published any R/C designs that I know of. That means, to put it bluntly, that ignoramuses like me with no design training are left to experiment by trial and error with conversions of vane designs. Perhaps the designers are reluctant to publish for fear at this early stage they might produce duds, but it is precisely now that we need some designs to experiment with. They can debug them later as experience develops. R/C Design Criteria. In the hope that this may spur the designers on and be of help to the rest of you in the meantime, here are my personal criteria for the ideal R/M design: (1) All Points of Sailing. The yacht must be reasonably good on all points of sailing, not just the beat and the run, because R/C courses normally involve all points of sailing. If the R/C course is several laps of an equilateral triangle, then reaching and/or running will account for two-thirds of the total distance. At Central Park we prefer a modified Olympic course, which starts and finishes halfway up the windward-leeward line and adds an extra windward-leeward loop on to the triangle, so that you end up with two legs of beating, two legs of reaching and one leg of running. (Since there is a tendency for the OOD to flatten the triangle to bring the far buoy in 133

i. MODEL BOATS closer for better visibility, the windward and leeward legs tend to get longer in practice.) Whichever course is used, windward work is always less than half of the total; and you do not get 3 points for winning the windward leg. It makes no difference on which leg or point of sailing you take the lead as long as you are ahead at the finish. Windward work is still important and getting a good start and the lead to windward is tactically quite important, but obviously you can concede 3 yards on the windward leg if you know you can make up 10 yards on the reach. Reaching has not been emphasised in vane, and, as might be expected, it is on this point of sailin of things—lower weights, less wetted surface and sail plans which are less critical or more forgiving of imperfect settings. In a steady good breeze acceleration ability may be less important than in fluky or puffy conditions. It has been widely accepted in vane racing that the heavier displacement hulls are better in light air on the theory that once they get moving they tend to coast from puff to puff while lighter boats tend to stall out between puffs. While this may be true for vane sailing conditions, the loss of acceleration from heavy displacement may be disastrous in R/C racing. If you cannot accelerate reasonably well, any one of up to eleven other boats can luff you up and stall you out in irons while passing you to leeward. Those reports from England that the 20-23 Ib. older vane designs are finding favour for R/C conversions are interesting and, to me, somewhat baffling. I can see that a larger displacement design can take the extra weight of the R/C with less modification than, say, a 16 lb. design and that it will be easier to get back to the design waterline, but I cannot see how they hope to compete when they encounter good R/C skippers with 14-16 lb. boats which have been developed for acceleration. Good R/C skippers on fluky days try to stay in the best winds on the pond, tacking to the puffs, a factor which seems to cancel out the superior coasting ability of the heavier hulls. Sail Plans. Sail plans and rigs must take into account that R/C racing involves many more points of sailing than is customary on vane. Some finely tuned vane boats, for example, have a very narrow “groove” in which they can work best to windward, or are really effective downwind only if they are wing-and-wing. This may work if your only objective is to hit some point on a very wide windward or leeward line as in vane. But a yacht which cannot pinch effectively above a leeward (right of way) boat will find itself in a lot of trouble, as will a boat which that there appears to be the largest difference in rt | among otherwise competitive vane designs. (2) Manoeuvrability. The yacht must be extremely manoeuvrable because R/C racing is done in fleets around complicated courses and involves racing rules and tactics. You will be in trouble if your boat is sluggish in tacking or if you are unable to give right of way. A basic tactic when you get the lead to windward is to “cover” the nearest good competitor, matching his tacks to keep your boat between him and the windward mark; but if he can tack faster than you, he can break your cover and begin catching up to you. It may not be enough simply to add an enormous spade rudder because manoeuvrability is a function of all sorts of factors—displacement, waterline, hull shape, keel configuration, skeg and/or rudder arrangement and, to some extent, even sail plan. (3) Acceleration. The yacht must have good accelera- tion ability, even at the expense of maximum speed ona long leg, because of the manoeuvring involved in R/C racing. A boat which stalls out when forced to tack or is slow to react to a new breeze puts the skipper at an enormous handicap. This suggests attention to a number cannot run effectively with both sails on the same side. § (Limp jibs downwind must be avoided—if all the vane techniques for correcting this fail, maybe you will have to go to a jib twitcher as a last resort.) Thus sail plans and the related fixtures have to become less critical and more | serviceable over all points of sailing and particular attention must be paid to reaching. The various methods of f increasing sail camber automatically as you open the i sails seem to offer promise. Geor ge Burg ess of Fleetwood and Vic Smeed to the contrary notwithstandi ng, I seriously doubt that the better R/C skippers will be using as many as four suits of sails. Instead skippers will work to develop one suit for winds up to 15 mph. or so and a storm suit. Here we have never held up vane starts to allow a skipper to change to a different rig, and the | situation in R/C racing is such that you rarely have a chance to change rigs. To give everyone as much racing as | Possible, R/C races are usually run off under very strict time schedules and often without even a lunch break. (If this sounds somewhat uncivilised, consider that there may be 30 skippers from a 150 mile radius all of whom have / come to race. The Race Committee is under considerable pressure to get each in as many races as possible but, because of frequency limits, can only race a maximum of 12 boats at a time.) Even if you can change rigs during a bye, you cannot tune or test it because another skipper is racing on your frequency. Thus whatever rig you put on before the race is probably what you will have to manage Manoeuvrability is crucial in R/C starts. In this RX race at CPMYC, four of the eight yachts are too early for the start and have very little room left for manoeuvre. At least three are headed for trouble, as the lower picture shows. Here the nearest yacht could not establish starboard tack right-of-way in time and | so is coasting in irons to the line. X 344 stalled successfully and then trimmed to drive for the line behind the two port-tack yachts heading for a three-way collision. The yacht nearest the mark has timed it perfectly and is in the best position, to wind= ward in clear air. 134

MARCH 1975 Chuck Black’s Warrior Il with an 85in. rig, a commercially available g.r.p. hull adapted by Standley Goodwin from a successful American vane design. with. I like to use a suit which is a little higher in aspect ratio than my hull can take in brisk winds. It gives me good action (what CPMYC Commodore Frank Soto calls a “goosey boat’’) in light air and when my hull gets overpowered, I can slack the main vang to spill wind from the top third of the main or even let out on the main sheet to let the main luff a bit. Although vane sailors here have abandoned travellers as too foul-prone, Standley Goodwin of Marblehead and Rich Matt of Riverside (Illinois) are strong proponents of travellers for R/C. When the wind picks up they can simply let the traveller go farther toward the leeward rail. (If you have trouble building the traditional jockey or it tends to foul, mayde you could try Andy Littlejohn’s trick of eliminating the jockey and simply running the sheet under the traveller bar.) If you can get by with such tricks to windward reasonably well, you should have an advantage off the wind over the fellow who has picked his storm sail for the conditions. (5) R/C Weight. The hull design must take into account the weight and placement of the on-board R/C equipment. Although some can bring the R/C in lighter, I would suggest a 2 Ib. allowance, most of which presumably will be placed as low as possible in the hull amidships (at the centre of gravity) with perhaps a 2-ounce rudder servo mounted right in front of the rudder post. (Although modern vanes weigh very little considering their mechanical sophistication, the removal! of the vane and related equipment will have a significant effect on fore and aft trim because of its placement so far aft.) Most R/C skippers here are very careful to keep their SCUs low in the hull, but Niel and I are continuing to use a hatch mounted system with the rotor above deck because we like to see it work. Several skippers (including D. J. Robinson of New Forest) are considering sealing the nicads and even the SCU permanently in the lead bulb, but I feel this is going too far. I have had enough trouble with moisture to be horrified at the idea of carrying that equipment underwater all the time, and how would you get at the nicad if a cell fails, or at the SCU to make a repair? Niel and I have worked very hard to keep our battery weight as low as possible, and we always take a spare set to a race so we can switch to a fresh set after a couple of hours to avoid any possibility of battery failure in the later races. (It is surprising how many races are lost toward the end of the day from battery failure.) To get the same safety factor in a keel battery mounting, presumably you would have to carry the equivalent of our two sets of batteries. I think other approaches to the weight problem are more promising. On my Ballantyne Arrow VI, which we finally have back to its original vane designed displacement, we have successfully compensated for the 14 lb. of R/C by dropping the keel an inch and taking the equivalent weight off the bulb. At Central Park we have been quite successful in keeping the hulls stiff enough by using deeper and narrower (to avoid increasing wetted surface) keels with lighter bulbs, but John Lewis points out that the deeper you go the more lift you get from the keel, which tends to reduce stiffness. Accordingly, experiments in rather modest increments may be in order. Although flat plates have been popular here for vane designs, the new building at Central Park, based on a great deal of study of the test reports of dinghy and keelboat designs, shows a pattern of very carefully worked keels with about an 8 to 1 camber and a fairly blunt leading edge. R/C Reliability. The designer has to take into account that any R/C breakdown can be disastrous, and so the design and rigging of the yacht, and particularly the R/C equipment and the SCU, must be as simple and troublefree as humanly possible. Under our rules (essentially the same as the TYRU rules), you are not allowed to touch your yacht after the preparatory signal has been given and a DNS will cost you points equal to the number of scheduled boats plus 2, in a system in which the lowest score wins and the first boat gets 3/4 points, the second gets 2 points, etc. Hulls must be absolutely watertight and hatches taped all around. Screws should be dipped in silicone rubber before insertion. Ian Bell uses a packet of silica gel in his R/C box to keep moisture away from his electronic gear, and Bob Harris has rigged up a small hifi fan to air out his hull after each day of racing. (Niel and I remove the R/C gear from the hull for the same reason—it is very easy since it is all mounted on the bottom of a hatch.) Sheets and fixtures must be laid out in a way to minimize the possibility of fouled lines since if a line fouls you will have to wait to the end of a race to fix it. Connecting wires on the R/C must be multistranded and should be positioned or tacked down in such a way that they cannot flex much. (A broken wire may be very hard to locate and repair at the pond,) Connectors should be taped together because they can come loose in a collision (quite common in fleet racing) or even a hard jibe. Roger Deal of California uses Velcro tapes to anchor his batteries firmly in the hull, and many use rubber bands to keep them from shifting. Although some manufacturers claim their receivers and servos are waterproof, I doubt if any can be swamped, so do not use a drain hole and if you do get any water in that “‘watertight” hull, sponge it out or use one of those model aircraft fuel bulbs as a pump. R/C enthusiasts are extremely inventive and I am sure one of them will soon invent a way to set a spinnaker by radio, but each of us must make a decision as to whether we want a reliable R/C racing boat or a floating R/C testing platform. Every piece of R/C gear which is not absolutely essential (like a separate jib SCU or a jib twitcher) is subject to breakdown and must be evaluated against that risk if you are serious about racing. 135

MODEL BOATS This R/C reliability problem cannot be stressed too much. In the American R/X Nationals last year, I lost first place when I took a DNS in one race (11 point penalty) because a wire to the rudder servo broke. Two yachts suffered from a bleeding transmitter, while another yacht lost SCU from battery weakness. Still another yacht had to drop out when a brand new set of batteries failed. Some R/C failures can be attributed to design problems, but most seem to result from avoidable human error. You simply have to treat your R/C as if your life depended on it—like packing your own parachute. Transmitters and receivers must be handled with extreme care and cannot be jounced around in a bike basket or in the boot of a car. They must be checked out and tuned professionally whenever they are suspect and, in any event, at least once a year. (A bleeding transmitter will make you very unpopular at the pond.) Nicads must be charged carefully and checked on a meter before every race, and even then carrying an extra set is an absolute FIGHTING FLEETS IN MINIATURE No.107 must. And do not go near the water unless your transmitter is around your neck! (7) Rudders and Skegs. Although several CPMYC members have achieved good manoeuvrability on suitable hulls with rather deep rudder-skeg combinations, Niel and I, like most R/C skippers in North America, have gone to spade rudders on Ms and 10Rs. We experimented with doubling the depth of the vane dimensions for rudder-skegs and they gave good control in fleet racing (stopped the broaching on the reaches in stiff winds), but we found that a similar hull with a spade with about the same wetted surface could be tacked three times as fast in some conditions! Spades take some practice to get used to precisely because the steering is so fast, and so most of our work to windward is done with the trim tab and not the main control. Whatever you use must be absolutely reliable under all conditions because in fleet racing you can seldom recover from a serious loss of control. Most failures occur in heavy reaching condi(Continued on page 140) (December 14th). It was in the British best interest that Graf Spee remain in Montevideo as long as possible, thus allowing the battle cruiser Renown, the carrier Ark Royal and the French battleship Strasbourg to reinforce Harwood’s small force. They were on their way but it would take them nearly six days to reach the mouth of the Plate. On the other hand the British had to appear The Battle of the River Plate to be in sufficient strength to take on Graf Spee immediately she emerged and, while pressing officially for her immediate departure, there were behind-the-scenes manoeuvrings to ensure that the German ship remained where she was. Deliberate rumours were fostered that Renown and Ark Royal were already off the Plate and, so successful were these, one German officer actually reported that he could see the two ships in question on the horizon. In the meantime arrangements had been made Part three – Conclusion By MICHAEL AINSWORTH WHEN Admiral Graf Spee steamed into the neutral port of Montevideo, Uruguay, on the evening of December 13th, 1939, she touched off a diplomatic battle that was to wage for another four days. The problem facing the Uruguayan authorities, not wishing to offend either Britain or Germany, was the interpretation of the Hague Convention of 1907, in which the rules concerning neutral and belligerent rights in wartime were spelled-out. Under International Lawa belligerent warship could not stay in a neutral port for longer than twenty-four hours unless it required repairs necessary to make it seaworthy. It could, in no circumstances, carry out repairs on armament or equipment that affected the ship’s ability to do battle. A further ruling, that was to feature significantly in this particular case, prohibited the sailing of a bellig- erent warship from a neutral port within twenty-four hours of the sailing of a merchant ship belonging to an opposing belligerent power. In the case of the Admiral Graf Spee the most serious damage was a hit near the bow on the port side which, if left unrepaired, would have jeopardized her chances of getting back to Germany ina North Atlantic winter. Of more consequence to Captain Langsdorf, however, was her shortage of ammunition, only enough, he calculated, for twenty minutes of battle. The Germans asked that their ship be allowed to stay for fifteen days. The local British representative insisted that the twenty-four hour limit be observed. The Uruguayans, after inspecting the ship, compromised at seventy-two hours. The British were in a peculiar situation. Only Ajax and Achilles were immediately available to prevent Graf Spee from breaking out of port. Cumberland was heading north from the Falklands at all possible speed to reinforce Harwood, but was not to arrive before late the next day 136 for a British merchantman to sail from Montevideo on December 15th to ensure that Graf Spee remained in port until at least the 16th. Langsdorf had in fact four options open to him. He could come out and fight; he could permit his ship to be interned at Montevideo; he could break out of Montevideo and head for Buenos Aires (the Argentine Government being pro-German in their sympathies) and be interned there; or he could scuttle his ship. Convinced that a superior force was waiting for him the first and third alternatives were discarded. Pride would not permit the Germans to accede to internment at Montevideo and the only remaining choice was to destroy the ship. Arrangements were put in hand for scuttling. All the British prisoners had been released upon arrival at Montevideo, and his injured crewmen had been transferred to local hospitals. Funeral services had been held for the dead. All but a skeleton crew were transferred to a German merchant ship in the port, secret equipment was destroyed, and the ship made ready for demolition. Harwood, now promoted to Rear-Admiral, planned to fight along the same lines as before, using his heavy cruiser, Cumberland, as one division and Ajax and Achilles as the other and forcing Graf Spee to divide its fire. The arrival of Cumberland was a major reinforcement for Force G. Undamaged, with a full complement of ammunition, and one extra eight inch turret as compared to Exeter, Cumberland made Harwood’s force even stronger than when they first went into action. But, much to the chagrin of Cumberland’s crew, she was not to see action, and had to content herself with a grandstand view of the dramatic events which followed. The Uruguayan Government had set a deadline of 2000 hours on the 17th, by which time the Graf Spee had to sail or be interned. No hint of Langsdorf’s inten-

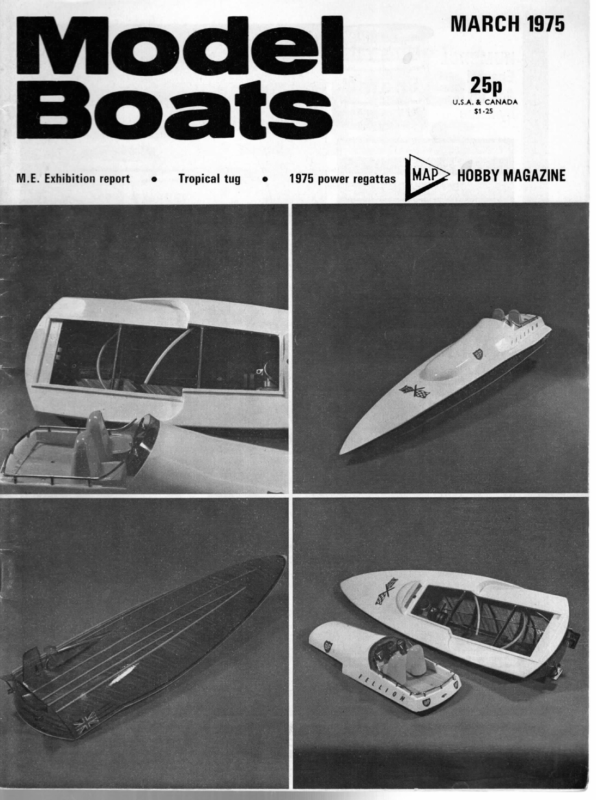

MODEL BOATS 14 RC 80 Folkestone MC. Lower Radnor Park Pond 10.30 a.m. Stg. IC & Elect. MR. | & Il. 10p class (splits). 14 21 RC No fee (splits) Scale inc. hard chine. All boats to have working navigation lights. Brighton & Hove SME. Hove Lagoon. 10.30 a.m. 25p boat (splits) MR. 20 min. I,lI & (III Sp.lg.). 27 April 4May 11 May 18 May 1 June 8June entry SAE. MINIMUM POINTS TO ENTER FINAL THIS YEAR = 10 Bromley MPBC Riverside Gardens, Orpington. 8.0 p.m. 21 RC 21 RC 21 RC 80 Kingfisher MPBC. Kingfisher Lake, Nth. Camp, Nr. 28 RC 80 Mid Essex BM. 10 a.m. MR. 30 min. ‘Dovercour t 1800’ Pre entry S.A.E. Drivers Duration Champs. Q.R. This is the final round in this Championship and the trophy 28 QUALIFYING EVENTS FOR SOUTHERN AREA STRAIGHT RUNNING CHAMPIONSHIPS RC 85 Eastbourne MPBC 10.30 a.m. MR. 30 min. Drivers Duration Champs. Q.R. (splits) Pre entry S.A.E. Bexley & Dis. MFBC. MR. I,Il & (III Sp.Ig.) 10 a.m. Pre Aldershot (adj. Nth Camp Stn), Scale IC, Steam. 11 a.m. 15p boat (splits). =SR Elect. & Swindon Mid Essex North London SME Welwyn G.C. Watford MMC Blackheath 29 13 7 14 28 June St. Albans July Victoria Sept. Kingsmere Sept. W. London MPBC Sept. Final—Victoria Park ORGANISERS FOR SOUTHERN AREA PRE-ENT RY REGATTAS 1975 Kingfisher M.P.B.C. Mr. Keith Newton, 26Wooteys Way, Tel. Alton 83885 (Home). presentation will be performed at this meeting. Alton, Hants. SOUTHERN AREA S.R. CHAMPIONSHIP. Victo ia Cygnets M.P.B.C. Mr. John Cundell, 12 Hillshaw Crescent, Strood, Kent. Tel. Gravesend 64261(Work) OCTOBER 5 RC 85 Stevenage MAMS. 10 a.m. MR. 30 min. Pursuit Chal lenge Trophy Duration Pre entry S.A.E. (splits). 5 SP East Essex H.C. Bradwell Wick 11 a.m. All classes. 12 RC Portsmouth & Dis. MPBC. Canoe Lake, Southsea. Bexley & District M.P.B.C. Mr. P. Atlee, 57 Sydney Road, Bexleyheath, Kent. Tel. 01-304 0633 (Home) Park 11 a.m. 12 19 Stevenage M.A.M.S. Mr. lan Boyle, 1 Ashbrook Cottages, Lower Ashbrook, Stevenage Road, Hitchin, Herts. Tel. Hitchin 54045 (Home) Dovercourt (Mid Essex B.M.) Mr. Don Harvey, 116 Rickstones Road, Witham, Essex CM8 2NB. Tel. Witham 5286 (Home) 11 a.m. Stg. IC & Elect. + novelty. Fee later. RC 85 Stevenage MAMS. 9.30 a.m. Pre entry S.A.E. (splits). The Henry J. Nicholls 1 Hr. MR. classes I,II (III Sp.tg). ig CONTROL CONFERENCE. Further details Eastbourne M.P.B.C. Mr. Graham Hunnisett, 2a North Street, Punnetts Town, Heathfield, Sussex TN21 9DT ater. Bournemouth & Poole M.P.B.C. Mr. Paul Firman, 53 Parkwood Road, SOUTHERN AREA A.G.M. Boscombe, Bournemouth, Dorset. Tel. B’mouth 45024 (Home) KEY—first figures are obviouly date, Second fi gures dB noise limit. SR- straight running. SP – hydroplanes (tethered). RC- radio control. MRStg.-RC steering. § p-RC speed. Sp. Ig.-spark multi-racing. ignition only. Splits -split frequencies will be used. Stg. K.O.-non radio steering knock-out. IC-internal combustion. 26 RADIO CONTROL YACHTING contiued from page 136 things being equal, sheer hull speed is very desirable for it helps to make up for skipper errors, but, if some hull speed on some points of sailing must be sacrificed to attain the other criteria I have specified, I would opt for the “‘goosier” boat. The trick is to get around the whole tions when, for one reason or another, the rudder fails to hold and the hull wheels up into the wind, hitting anything in its path. A deeper rudder might help but, as Vic Smeed points out, if your hull heels too much the rudder starts to act like an elevator and its extra depth will not course ahead of the rest of the fleet, and whether this is accomplished primarily with superior hull speed, help. Spades have a tendency to be erratic if more than about a third of the total area is ahead of the rod. I am manoeuvrability and acceleration, or strategy does not matter much to me. It is, however, very frustrating to the not convinced that the reports from England, to the effect that the skippers are settling on spades with 2 in. by 7 in. skipper to race with a very fast boat which is sluggish in or 8 in. dimensions, necessarily indicate what we will end up with. I think we may be able to get by with smaller ones as we learn better how to control heel by radio, but you have to be pretty quick on the stick to spill wind just manoeuvrability and acceleration because he is always limited in his tactics and has to spend a great deal of time trying to stay out of the way of the rest of the fleet. Virtually all modern vane designs seem to have waterlines of 50} in., presumably because the designers are reaching for maximum hull speed, but I wonder if the rationale of that consensus should not be reanalyzed. Does maximum waterline help under less than optimum wind conditions ? Does maximum waterline make it more difficult to design for lowest P.C.? How would a 46 in. before you broach. (8) Hull Speed and Directional Stability. Sheer hull speed and directional stability are relatively less importan t in R/C. From my extensive experience in losing to expert vane skippers, I conclude that two essentials to success in vane racing are: (1) a fast directionally stable yacht, and (2) the unique ability of the canny vane skipper to read waterline 14 Ib. hull, which begins to plane in 10 mph. the conditions and make correct settings before he lets his boat go. On the other hand, R/C allows for continuo us winds, do against a 20 Ib. full waterline vane conversion around an R/C course in a variety of wind conditions? Others may suggest additional criteria or state them in different terms, but these should make a pretty good set for starters. As you develop your own set and your own rationale, it would be well to keep in mind that R/C racing, unlike vane racing, involves: (a) continuous control of sails and rudder, (b) running starts, (c) Olympic, or at least triangular, courses, (d) fleet racing, tactics and rights of way rules, (e) a very different scoring changes in settings; and, in terms of ability, the emphasis switches to the ability to keep changing the settings as the conditions around the various legs of the course require. (Errors can be corrected immediately as they become apparent but since you are always in control you can always make other mistakes, whereas a lucky vane setting may carry your yacht the whole length of the pond.) Too much directional stability will actually be a hindrance to manoeuvrability, but a very unstable boat which requires constant rudder correction (always involving a braking action) will undoubtedly lose out to system, and (f) the extra weight and reliability problems of the R/C equipment. (To be continued) (* The Editor does not necessarily agree! ) reasonably R/C designed compromise. Of course, other SURFURY The boat on the cover, built as a first-ever model made by John Bennion of the Potteries club, is to the MM plan of Surfury and is a stringer and frame hull with triple diagonal planking using scrap veneer wrapping from a timber merchant’s scrapheap. Deck is } in. softwood, also scrap, and the same wood was used for the superstructure. Handrail is tin. brazing rod and the only ready-made items were prop and shaft, rudder, helm wheels, turnbuckles for trim tabs, a McCoy engine and transfers. Odds and ends provided the rest — e.g. the control panel from a cigar box etc. John says that he learnt a lot from mistakes on this model and should do better next time….. 140