- Description of contents

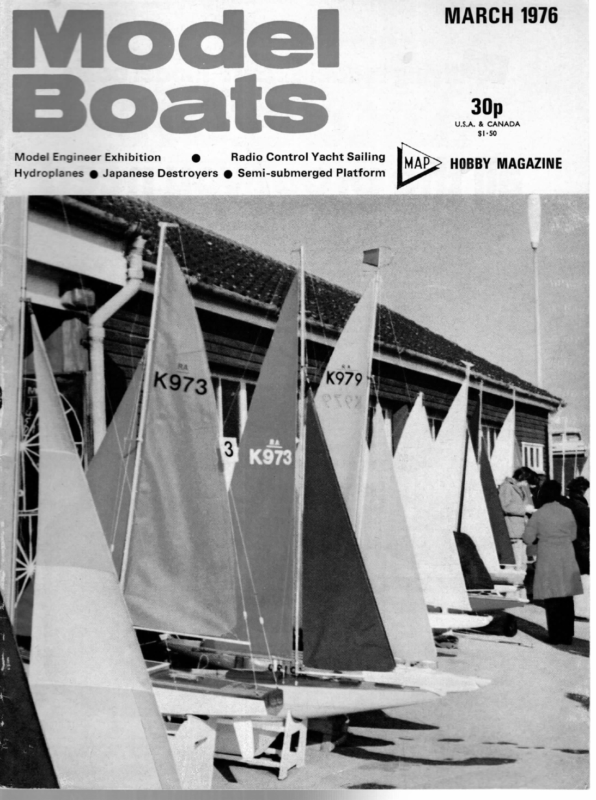

MARCH 1976 30p U.S.A. & CANADA $1-50 Model Engineer Exhibition @ Radio Control Yacht Sailing Hydroplanes @ Japanese Destroyers @ Semi-submerged Platform HOBBY MAGAZINE

MODEL BOATS The International “A” Class— a stability study By John Lewis Lye the last few years we have seen a number of changes in design trends in the International A class model yachts, some of which are superficial and emotive and some more fundamentally concerning the basic reasoning which lay behind the formulation of the rule. There has always been a strong lobby of people who feel that the visual effect of the yachts produced by the rule should not change, or at any rate only very slowly. It is important to them that the model should imitate the full size counterpart, but very often although a visual change in style may appear significant it may have little material effect on performance. Some traditionalists frequently fail to observe the changes occurring in the full size yachting scene and are really seeking to retain past images rapidly VERTICAL becoming obsolete. However, the A class rule was also intended to keep the yachts within a particular range of size and displacement, beyond which penalties are applied which should have the effect of making such designs non-competitive. For some C of G years design trends followed the well established path of progressive growth in waterline length and displacem ent. RIGHTING Indeed 60in LWL and over 70 pounds displacement was making the class only suitable for the very strong armed brigade of ex-rugby players. The few attempts to reduce ARM displacement below the rule penalty limit met with scant success, but these yachts had normal types of fin keel and thus did not exploit the advantages to be gained by using the rater type of bulb keel now used to enhance stability of the model. Perhaps it was significant, though, that the most generally successful designs were close to the lower limit of displacement without penalty. At the same time the efficiency of sail plans has improved by the use of better materials, and certainly a much more proficient under- standing of the theory and practice of obtaining driving force from the sail plan and the optimising of sailing trims has developed. Thus we now see small sail area, light displacem ent models sailing fully competitively with the larger, more traditional types within the class. In fact these smaller models may be proving to be superior and many people will welcome the trend as the models are less difficult to transport and less demanding physically to sail. It says a lot for the rule that such divergencies of design can be raced together and that these changes have not yet in themselves called for rule modifications. Top, Hughie Shields’ Glen Livit at 38Ibs and left, Bob Burton’s Roulette at approx 4Iilbs (chequered spinnaker, here sailing Eric Carter’s Streak, Maverick) are examples of light A boats with bulb keels which are competitive. (MB pictures) 134

MARCH Because so much comment can be made about stability and its prime importance on a design factor, I thought it would be extremely interesting to do a theoretical study of the stability characteristics of several typical A class designs. 0-40}— It is not my intention to describe in detail how stability calculations are carried out, as this can be found by reference to a competent text book on naval architecture, but suffice to say that the process is tedious and time consuming. For this reason it is rare for a sailing yacht architect to carry out a full study of stability and various, often misleading, rules of thumb are used when making comparisons from design to design. In the model yacht field I doubt if these figures have ever been worked out before and I hope that these data will form the basis of he 0-30) Design A — A heavyweight of 78.2 pounds dis- 2. Design B — A normal design of 63 pounds displace- 3. | lower the complete VCG. For the designs chosen the distances of the VCG below -+-4+} + { | + eS rm Lead i 4 = 0-20} rt . Eos —t 4 e oH a} Sed a |tease y | Lo x a | A Ye | ata | | | ie DESIG N.B. | ; VA 7a al a cai “DeSIGN.D Tle + —— 4 CoeNea io Uk 4 | = i —— | es ee ee ee 10° ANGLE | at | SS OF HEEL 20° ‘le siete i ee 4 LZ 7+ 4 Yi {4 EP I + + + + + | ” } } fret : Design C — A ‘lightweight’ 45lb displacement penalty type with bulb type fin . Design D – As for design C but with non bulbed fin. No useful calculation of stability can be carried out without firstly calculating the vertical centre of gravity (VCG) of the complete yacht. Note that it is not the centre of gravity of the lead that is used, as this is only one factor in the final centre of gravity and it is this latter figure which is all important. Of course a good ballast ratio helps to Ls cy em Genie oe bedST ee (a ment aie DESIGN.C. rT | }——+—+—4–4 0-05+- placement | A, & 9.25 | | | 2 better informed comment on the subject. The designs chosen for the study are: 1. RIGHTING ARMS pee 1976 14 | cl == | ae Pebah 30° wp| ——= 40° Not surprisingly the heavyweight design with its inevitably greater beam shows a more stable curve than design B. But look at the lightweight with bulb keel, for not withstanding the narrowest beam on LWL the righting arm is significantly greater than any of the other designs. Design D is just not in the same league. An interesting point did arise during the calculations and that is concerning the buoyancy which is contained in the bulb keel itself. Obviously this volume of displacement so the load waterline worked out at: Design A 5.98 inches below LWL Design B 5.65 inches below LWL Design C 6.67 inches below LWL Design D 4.53 inches below LWL It is immediately seen that the lightweight bulb keel design C has the lowest VCG and is in fact some 2in lower when compared with design D, the non-bulb equivalent. Later figures will show just how important this is in terms of sail carrying power. Also note how, except for the bulb keel version, the heavier yachts have the lower VCGs and this is fairly obviously due to the improved ballast ratio potential of the heavier boat. Incidentally, the VCGs were calculated by taking moments of actual weights of component parts and none of the chosen designs represent extreme examples of ultra lightweight construction but are all to about the same standard for comparative purposes. Any one of the examples is capable of improvement but the degree of improvement is bound to be greater with the bigger boat rather than the lightweight. There is more scope to ‘go’ at. We now have to establish, for various angles of heel, to what extent the Centre of Buoyancy (CB) moves outboard from the upright centre line. It is the degree of this movement which establishes the stability characteristics of a particular hull shape and the distances between the vertical line on which the heeled CB lies and the VCG is known as the Righting Arm. Figure 1 shows a typical heeled section and the positions of VCG and CB. This example is of the design A and is in fact Peter Pym owned by the Pollahn brothers of Hamburg. Figure 2 shows how the Righting Arms of the chosen designs vary with angles of heel arranged in graphical form. I did not bother to examine the situation beyond 40° angle of heel as by this time the yacht is sailing with gunwale right down and is perhaps beyond the point at which sail should be reduced to obtain maximum speed. Right, Roger Stollery and Clockwork Orange, bulb keel, 553in. w.|., 3641bs, and 1016sq.ins. with, far right, a ‘‘legal” version with a deck, Ricochet, built by Phil Bussey and now owned by Johnnie Hyde. Both are competitive. (MB photos) 135 low below the LWL does have the effect of reducing the outboard movement of CB on heeling. The effect of this is quite significant in that it reduced the effect of the lower VCG by a full one inch at an angle of 20°. Thus the difference of 2in in VCG between designs C and D is halved in terms of stability effect. Therefore it is probably possible that a good fin keel design with absolutely everything done to lower the VCG but without undue thickening of the fin at the lower level lines could have as much stability as a bulb keel design of indifferent construction. The moral is therefore that even with a bulb keel you cannot afford to be slack in taking advantage of all means to keep the VCG low.

|| RIGHTING the heavyweight may carry its sail to windward with __MOMENTS greater ease than the smaller boat but it does not mean that MOMENT ibs/ft she will be faster. Stability, although one of the prime factors in a yacht’s ability, is but only one and one must not forget wavemaking resistance and skin friction. We have all noticed how the big heavyweights achieve their best racewinning form in light air rather than in heavy winds. This is because wavemaking is at a minimum and the sail area available for the heavy boat tends to be greater than that of the lightweight. The skin friction factor can remain ae ite on a similar basis if the designs are equally good. RIGHTING On the other hand, given two designs of somewhat similar dimensions and characteristics the one with the greater stability will be the better boat. It is when the displacements differ considerably that the windward performance comparisons become so difficult and of course in 8 6 any sort of reasonable breeze and in strong winds the 4 heavyweight cannot live with the lightweight off the wind. 2 ° 10° ANGLE OF 30° HEEL 40° Now let us look at Fig. 3, which is a graph of Righting Moments. The righting moment is the product of the righting arm and displacement and thus more truly represents the ‘power’ of the design in terms of ability to carry its sail. It can be said therefore that this graph represents a true picture of the relative stabilities of the design. Design A shows the advantage that the heavyweight yacht has in this respect, for its ability is roughly twice that of the lightweight fin keel design, 37 per cent greater than the bulb keel and 22 per cent greater than the normal 63 pounder. This is very interesting but what does the information do for us? Does this mean that the big heavyweight is therefore the best bet for competitive racing? It does mean that FIG.4 SAIL POWER = / bulb keels are used. Just how light one can go is difficult to determine, but in order to obtain a respectable sail area it will also be necessary to reduce LWL, which in itself reduces the speed potential. There must also be a minimum t | | 7. loesién. BLA sail area below which too much driving force is lost for any form of design. Bearing in mind that the heights of the mainsail and jib, and therefore the lengths of the luffs of the sails, are virtually fixed, any reduction in area is accompanied by an increase in aspect ratio. We all know that higher aspect ratios produce relatively more efficient sail configuration. Therefore, a reduction in area within the A class rule does > || lino! sPeeo—— 9 oe Pepe Te g & o-3}—- not producea pro rata reduction in driving force. This also tends to support the lightweight concept of design. In fact | o1}-—4 —T 5 + 10 ANGLE OF HEEL—— 10° 15 if I were to be choosing dimensions for a new design right — now I would put the sail area between 1150 and 1200 square inches and the LWL between 55in and 57in with a } eal 20 — WIND SPEED MPH 20° THE POWER SCENE apparent position over the lightweight bulb keel design. In fact if the so-called normal design B was still a normal displacement of say 56 to 58lbs we would probably see that the sail carrying power just about equates with the lightweight design. Fora given angle of heel, say 24°, wesee that there is only 1 mph difference in wind velocity required to achieve that angle between designs B and C. In all examples the graphs show that the lightweight without bulb keel just should not be competitive. By and large this stability study together with some more generalised consideration of design parameters does support the trend towards lighter displacements as long as _ DESIGN. A: % © & DD 2 CARRYING 9 $ °°269 9© WIND PRESSURE IN POUNDS PER S QUARE FOOT — Ibs/sq ft fo} peal | | TT We now need to bring sail area into the equation and for the designs chosen we have: Design A -—10.09 sq ft C -— 7.99 sq ft B —-9.02 sq ft D – 7.99 sq ft These figures when compensated for angle of heel can be related to wind pressure, wind velocity and angle of heel. This relationship is shown in Figure 4 and we now see that the big heavy boat does not enjoy quite such a good 30° displacement of between 39 and 45 pounds. 40° (continued from page 139) capable of Naviga triangle times of 30-31 secs. for nearly 6 minutes despite the weight of the glassfibre hulls used. With the parallel connected Searam at 10 volts and 40 amps, it is important to use thick wiring and bus-bars to avoid loss of volts. A given resistance in circuit with the parallel connection has four times the effect on performance as with the series connection of commutators. Undoubtedly the main factor influencing the choice between 1.2 or 4a-h cells, if one has the option of either, is the cost. In Australia, and probably throughout the world, the 10 4D cells necessary for 4 minute 400 watt operation cost only half as much as the 32 1.2 a-h cells 136 which I use with the SeaHorse at the same power. The 4D cells is not capable of being charged at the same ultra-rapid rate as the smaller cell, but can still be charged from flat in 15-30 minutes which is sufficiently fast in my opinion. The 10 cell combination used on the Searam may also be charged in one block directly from a car battery charger which is another useful feature. Ray Kroker in the States, I know, advocates the use of seven 4D cells on his Sea Wasp 6 motors for operation at 15-20 amps and has found it possible to run for 18 minutes at 15 amps. Such a combination would prove an excellent balance between speed, running time and cost for anyone not wanting an out-and-out competition performance.

MUM q MODEL BOATS Rule 39 — A Windward yacht may not bear off of the wind to prevent a Leeward yacht or a yacht clear astern from passing, if the latter is within 3 lengths A windward yacht may not \ bear down on a leeward Fla yacht clear astern to prevent her from passing rf 4 ’ AC H I Continuing Charles Brazier’s through the lee _-~, 4 ce / 4 € The reader is ‘Red’ and Charles is =p. The following diagrams will help in understanding Rule 37.2 and make clear the definition of Clear Astern and ow yy 4 updated notes on radio racing rules. sailing ‘Blue’. ria rayi rs RAC ! N G Clear Ahead. re Pik BLUE Overlap commencing if between ‘B’ & ‘C’ Overtaking leeward Cc yacht / ‘A’ is clear astern of ‘B’ 7 | ‘D’ is clear ahead 4 By reason of my having an Anti-Barging rule start, you have got over the line ahead of me, but | ofc! Iam following up astern to leeward and am within three lengths of you. Hold your proper course and steer nothing to leeward of it. You will be penalized if you prevent my passing in this way. I am going to try and sail through your lee. The definition of Bearing Off or Bearing Away is altering | If ‘B’ is overtaking ‘C’ the overlap remains course away from the wind. Rule 37.2 — A yacht Clear Astern must keep clear of a yacht lear Ahead Clear Ahea until she is clear CLEAR ASTERN ahead of ‘C’ OVERLAP CLEAR AHEAD Rule 37.1 — A windward yacht shall keep clear of a leeward yacht ae The following sketch best describes this. At this moment in a race things really start to get exciting, for the leeward yacht is approaching the time when he can use the Rule which allows him to slow up his opponent, and better his position. Blue was overtaking =) but not keeping clear ay enough. Red altered course to starboard in order to carry Se out her obligations as windward In so doing, her stern hit boat. Blue. Blue is disqualified Not more than This rule ties up with Rule 39. I am faster than you and 2 boats lengths am overhauling to leeward, because you are obeying Rule between them for 39 by not bearing down on me. I, the overtaking yacht, am also governed by rule and must not pass so close to you as to make it difficult for you to keep clear. the purpose of this rule RED is closest to the IfI do not observe this and a collision ensues I will be — direction from which the penalised. However, I have observed the overtaking Rule wind is coming and is From the moment an overlap is established I cease to be overtaking yacht and become leeward yacht. Thus we come to the next rule in our race. and must keep clear of BLUE tha loeward ht i! ee and we now overlap. q : 140 therefore windward yacht

Rule 38 — Luffing after Starting. After a yacht has started and cleared the Starting Line she may luff as she pleases to prevent a yacht on the same tack from passing her to Windward oy ve — eae a Lee —— | _—* – “Course after lefFiny eee eee or ae ee Rule 41 — A yacht may not change tack unless she can complete the tack at least two overall boat lengths from her opponent, or other yachts on a tack. (Above) By reason of the wind and the position of the next mark of the course, you and I are not going to make the buoy er original course without Tacking. We are both on the Port Tack. lam ahead as a result of our little luffing match. I have judged that I am far enough ahead of you to go about on to the starboard Tack. I hail ‘going about’ and do so. Should my ~\ Line showing leeward yacht clear ahead at the commencement of luffing judgment have been wrong andI tacked so close that you are unable to avoid me, even although you tried to do so, I would be penalized, in spite of the fact that at the moment of impact I was on the Starboard Right of Way tack, because I had tacked too close. However, we have not collided in fact, so let us go on with the race. The definition of luffing is — altering course toward the wind until head to wind, but not beyond head to wind. Our race is progressing well, but let us take stock of the situation between us. I have overtaken you and am to leeward. You have ample room to keep clear, gradually I am hauling ahead while you, still to Windward, are dropping astern until Iam Clear Ahead of you to Leeward. Blue is now ina position to prevent you from passing to Windward. Because you are the Windward yacht, you must keep clear as described in Rule 37.1. I note that you have started to catch up and it is time I acy to defend my position, by luffing you up toward the Rule 42.1(a) — An outside yacht shall give room to an inside yacht at a turning mark of the course. You have won for yourself a position between me and the buoy and we overlap. You are therefore inside yacht “sie I on the outside must give you room to round the uoy. You must claim your overlap by hailing ‘Overlap’ and will be allowed this claim unless the OOD or a judge states you do not have one. Rule 42.3(a), modified for wind. In carrying out the Luff I have prevented you from passing and slowed you down. Before I too lose too much way, I quickly return to my proper course. The quicker I am able to do this the better, for it may mean I shall gain a few yards. The IYRU rule concerning when luffing must cease, namely when the helmsman of the windward yacht has been abreast or forward of the mainmast of the leeward yacht, is far too difficult for radio controlled yachts to radio control sailing, should be understood. You cannot . claim your overlap unless you have established it before the yacht clear ahead is within four of her own lengths of the buoy. (to be continued) a observe. For our purpose, then, the Luffing may continue all the time and overlap exists. It should be observed that the rule states that a yacht clear ahead or a leeward yacht may luff as she pleases except that in the case of the leeward yacht she cannot luff if the windward yacht has been clear ahead at or since the start. She must get clear ahead before having this right. If there is an overlap existing at the start, however, the leeward yacht may luff to prevent her opponent from / 4 4 gaining the advantage of that position. Under these conditions if the luffing yacht touches the windward yacht the latter will be penalized for having failed to keep clear whilst windward boat. For the purpose of these Rules, overlapping is only established when yachts are not more than two lengths away from each other. This modified version of the TYRU Luffing rule simplifies the luffing for radio controlled yachts. We must have luffing of a sort and I believe this to be the answer. One last word on Luffing. Always remember it is a defensive action, never regard it as an offensive one. i : : eG ei ya 7 a – nd le a =. ~ ‘ A \ wind. / / / An outside yacht gives room to an inside yacht. This applies whether running down wind, or beating to windward, or reaching 141 \ ‘