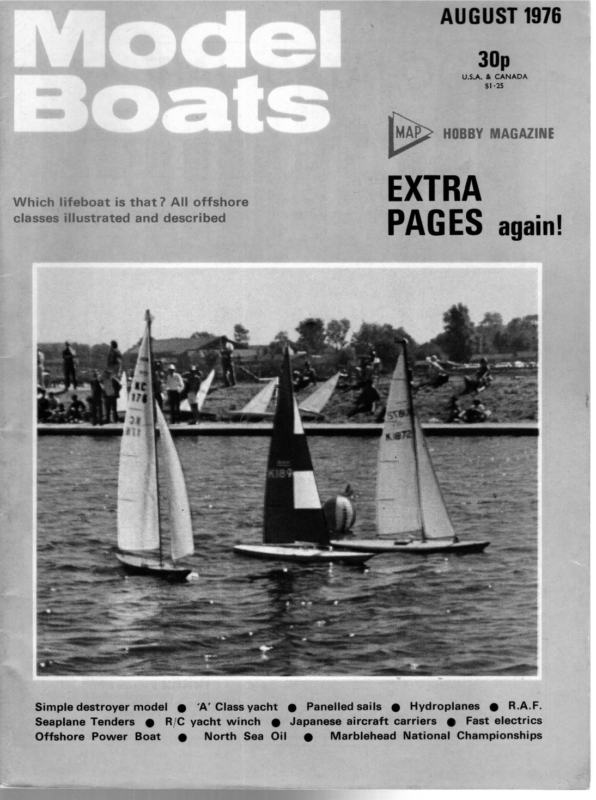

AUGUST 1976 30p U.S.A. & CANADA $1-25 HOBBY MAGAZINE Which lifeboat is that? All offshore : EXTRA PAG ES j again! — classes illustrated and described Simple destroyer model @ ‘A’ Class yacht @ Panelledsails @ Hydroplanes @ R.A.F. Seaplane Tenders @ R/C yacht winch @ Japanese aircraft carriers @ Fast electrics Offshore Power Boat @ North Sea Oil @ Marblehead National Championships

MODEL BOATS Making _- MAX. CAMBER | ———— “ 4 | _— HEAD Eines FIG. | nrnaek CHORD Panelled FIG.2 Sails Bill Van Dieren, Commodore of the year-old Vancouver club, wrote these notes for the club newsletter, but they are of interest to all yachtsmen. HIS article describes the methods and materials used for making sails for my 50/800 De Klomp II, which is a modified Mad Hatter designed by R. Stollery. Many years of racing in small dinghies, Star boats and my Cal.25 racing-cruising boat showed that to do well and finish regularly in the top three, the following are required: 1. The boat must be clean and smooth. 2. All gear and rigging must be reliable. 3. Sail the shortest course. 4. Know your racing rules and apply racing tactics in a fair way. 5. Sails must be properly shaped and trimmed for the conditions at the time. It should be clear that while superb sails may help in placing better, one tactical error during a race may drop a boat from first to last place. Design Criteria Sail for a sailboat is of the same importance as a motor is for a power boat. Sails can be better compared, however, with the wings of a glider; in actual fact, the sails on a boat are really vertical mounted wings. Wing shape or air foil is extremely important. Wing shape varies, depending on the air velocity over the wing. It is only comparatively recently that an Italian aeronautical engineer did wind tunnel tests with several different airfoils at a wind speed of ten miles/hour, which fits our purpose quite well. The results of those tests showed what had already been known by sailors and sailmakers through experimentation and experience. Generally, the sail shape, 12 inches above the foot, should approximate Figure 1. The chord is the width of the sail. Maximum depth of camber is 15 per cent of chord; however, some sailors prefer 10 per cent up to 20 per cent. The point of maximum camber should be at 35 per cent of chord from the luff. A loose footed sail cut in one piece from a pattern (flat cut sail) has no airfoil, or bag as it is called, and if the clew is adjusted to provide bag, then the maximum camber will be at the 50 per cent chord, see Figure 2, which cannot provide as much drive as a sail shaped as per Figure 1. 452 17 FOOT det SAIL \cuew ‘tack PLAN FIG. 3. Materials The best sail material is Dacron. I use 140z soft Dacron and it is plenty strong enough for boats up to 7ft in length. Sewing thread should be of a synthetic material; do not use cotton. Use a sharp modeller’s knife or razor blade for cutting, or a hot iron, if you have one; a hot iron seals the edges. However, I seal the leach and foot by applying colourless thinned model aircraft dope, and nail polish could also be used for sealing. Several sheets of smooth white cardboard should be obtained for pattern layout. (Dacron is a trade name originating in North America. In U.K. hot-rolled dinghy nylon is commonly usedfor sails—Ed.) Mainsail Three sheets of white cardboard were required to draw the sailplan. The sheets were joined with draughting tape in such a manner that they fold easily for storage. Select the sailplan required for your boat. The plans may provide three or four different sail plans. One should stay away from the extremely high aspect ratio sails until one knows the principles of fine tuning a boat and sails, as all adjustments become more critical, including mast bend, etc. The sailplan developed here is as shown on Figure 3. Figure 4 shows the mainsail laid out, which will be followed step by step. 1. Draw outline of mainsail in dashed lines, conforming to outline in Figure 3, except allow #in. for head. 2. Draw a solid line (final cutting line) tin. ahead of

AUGUST the luff, which is the allowance for a luff rope, or this material can be folded in case of ‘hook and jackline’ systems. 3. Divide leach in five equal parts and draw four centrelines at 90 degree angles to the dotted leach. Top batten line to be 14in. on both sides of dotted leach. The other three batten lines to be 2in. on both sides of dotted leach. first mast had an S-shape, as too much sail material was cut away at one point. Your sail and mast are one unit they must be matched for good performance. Foresail or Jib The procedure to lay out the jib is very similar to the mainsail: 1. Draw outline in dotted lines, see Figure 4. 2. Draw solid line }in. ahead of luff, which is the 4. Connect head with extremes of battens and to clew, which gives the outline of final cutting line of leach. 5. Draw a curve at foot of sail; maximum distance allowed is one inch. Now a solid line has been established around the sail, which is the Final Cut- allowance for the forestay. 3. Divide leach in four equal parts and draw four centrelines at 90 degree angles to the dotted leach. Top batten line to be ?in. on both sides of dotted leach, the other batten lines to be lin. on both sides ting Line. 6. Draw a line (Panel Trim Line) around the Final Cutting Line, leaving a gap of 2 or 3 inches. Leave of leach. HAuns . Connect head with extremes of battens and to clew. . Draw curved foot, maximum roach is one inch. . Proceed as shown on Figure 4 and as described under an additional 5 or 6 inches at the head. 7. The panels are now drawn at 90 degrees to the dotted leach. The first line must pass through the tack. Then mark off and draw the remainder of the panels. Panels are 4 inches wide. (Note: Fewer panels can be used, but at the sacrifice of sail shape. The larger the number of panels, the better the maximum camber and camber location can be controlled.) 8. Mark maximum camber point on foot, which is -35 x 17=5-95, say 6 inches, from tack. Mark another maximum camber point near Panel 10 and draw line through sail. Number the panels, for later reference and orientation. 9. Mark off at the dotted luff line the dimensions as shown, starting at +,in. at Panel No. 11 to in. at Panel No. 2. Dimensions must be marked above the original panel lines, except for the fin. dimension 1976 mainsail. General The making of a suit of sails of the narrow panel variety requires a lot of patience and precise work. There are other methods of making sails, and other cuts of sails are also used, as is indicated in books on this subject. This article has been prepared to show the sailor how a sail is made, giving full dimensions, so that it will not be a mystery any more. In case your wife or girlfriend does the sewing, I recommend that you take them out for a special dinner or treat, as they will have deserved it! at the foot of the sail, which must be marked below the panel line. Also mark off in. on top of Panel No. 1 line at the leach. Draw curved lines along a spline or piece of 4 x #;in. spruce, as shown. 10. Take the sail material and lay over the pattern so that the edge line (selvedge) on the sail cloth lies parallel with the leach. Weight down the material ae ee the maximum camber line lightly on the cloth. 11. Cut out panels to panel trim line and be sure to remove the small wedges. Meus Wels 124 12. Now sew the panels together, always matching the maximum camber points. Overlap panels }in. precisely and sew with one straight stitch only. 13. Lay completed cloth over pattern, so that seam at Panel No. 1 matches, now pin down the tack. Carefully tighten the luff, while leaving baggy material in centre and try to line up baggy material with maximum camber line. Pin down cloth at head and now carefully tighten foot and leach, then pin down the clew. 14. Mark a pencil line on the cloth showing the dotted luff line, now cut cloth to Final Cutting Line. 15. Two people should now hold cut out sail and adjust stitching if required to remove bulges or flat spots, then zig-zag stitch all panel joints and sew in the luff line using a straight stitch. Sew on the batten pockets, corner reinforcing, etc. (Note: Do not worry if the sail is not perfectly shaped as you are now 6 becoming very precise. The sail with some minor imperfection is far superior to a flat cut sail.) 16. Put the sail on the mast and adjust luff line location if bulges or hard spots show up. Stitch the luff line for the second time. Seal edges, make and install battens. In case the sail is too full for windy weather, bend the mast to flatten the sail. A wooden mast can be steamed in any permanent shape to suit the cut of your sail, therefore bend your mast if you have made a small error. My 453

AUGUST I PROMISED myself some two years ago that it was not reasonable for me to design another international A class without having analysed the factors involved in the modern trend towards lighter displacements. Having spent so much time in developing the big heavy yachts in the class, it is not easy to change tack and adopt a different design philosophy. I am not prepared to do so without some rational reason, as merely copying the fashion would produce no satisfaction for me and in the long run the quality of design would suffer. Accordingly, I carried out a series of calculations on the comparative stability of various knownA class designs and the results of this study were published in the March ’76 issue of Model Boats. The data produced by the calculations plus some more rather subjective or qualitative reasoning leads me at this time to favour lighter displacements, provided the designs show the use of bulbous fin keels. Although I have an instinctive liking for the biggest possible yacht and also the classical curved lines which the bigger displacements make appropriate, the overriding factor must be the ability to win races. At the end of my stability study I wrote “if I were choosing dimensions for a new design right now I would put the sail area between 1150 and 1200sq.in. and the LWL between 55 and 57 inches with a displacement of between 39 and 45 pounds”’. Perhaps it is understandable that for the design of Quasar I went to the longer and heavier end of this chosen range. This is by no means the first light displacement A class designed by me, for way back in 1955 a design was pre- pared and although a pretty half model hangs on my lounge wall, the actual yacht was never built and raced. Then about six years ago I did a design for a member of a northern club which showed distinct signs of competitiveness but did not enjoy a properly developed bulb keel for stability. There is another design similar in dimensions to Quasar but of different hull form currently being built both in this country and Europe. It will be very interesting to see how these two new designs compare. 1976 A 451i lb ‘A’ boat from the board of John Lewis The hull form of Quasar follows my usual and well-tried shape with a midsection giving maximum stability with narrow waterline beam and shallow canoe body. The shoulders are fairly full and should pay dividends when going to windward in a smart blow. I have not given the hull a very sharp entry and exaggerated planing body aft, as with the lighter displacement and moderate other dimensions, particularly beam, the hull will plane quite readily and will not change trim when doing so. The transition from displacement speeds is therefore very smooth and it also enables the particular type of fin keel and ballast bulb to be used. I will mention this again later. Particularly to windward I like to see a yacht using all of her length and this new design should do this very well with the powerful bows and moderately lean after sections. The quarter beam length is just up to the maximum allowed by the rule and no distortion of the hull lines has been permitted to cheat the meaning of the rule and provide unnaturally low overhangs of dubious value. The diagonals and buttocks run out in straight lines and this usually provides the fastest form of hull. The overhangs have been left short as I wanted to produce a boat that is handy to transport and that would be suitable for radio control as well as free sailing. This dual purpose is also seen in the rudder design where it will be noticed that there is no skeg in front of the rudder. I have done this in two previous free sailing A class and no apparent disadvantages emerged, but for radio control a quicker rudder response is likely. It is also easy to build alternative rudders of larger area if the skipper and/or local sailing conditions make this desirable. Theoretically a ‘spade’ rudder without a skeg should lose efficiency and stall at the larger angles of helm, therefore providing the rudder is big enough small angles should be adequate and all is well. Plans give half-size hull lines, {“size sail.JRef. MM1218, peice £1.15 ret de and post from M.M. Plans, P.O. Box 35, Hemel Hempstead. erts QUASAR (18 Model Maker Plans Service DS Secge Street, Heme! Hemostead. Herts. IHN

MODEL BOATS There is no ‘bustle’ on this design, only a stub fairing for the rudder root which also assists directional stability. Bustles are fast going out of fashion and in any case should have no place in light displacement designs where the aft sections can be made suitable for a clear delivery of the water. This is another advantage of the more symmetrical hull form, as bustle design is very critical and can probably only be optimised in a towing tank under careful and skilful scrutiny. I would still attempt to design a suitable bustle on a heavy displacement A boat, as there are one or two subsidiary advantages as well as the main one of slow separation. Now let us look at the fin keel and ballast. One of the reasons that I am not very happy with a ballast bulb is that it produces a significant chunk of wetted surface and associated resistance. The complex shapes one sees in some bulbs may look streamlined but I would not be surprised if the resistance was extremely high. The advantages of the lower CG outweigh all the disadvantages, but nevertheless if the bulb could be made to do some useful additional work so much the better. Some years ago Ken Jones and I did some experimental work with Col H. G. Hasler to try and develop an ocean cruising or racing design which followed a concept of extreme simplicity, efficiency and low cost. As a result of this work I designed a 10 rater called Logic which embodied the best features of our experiments to see how competitive the ideas were. Logic had twin keels, so as is usual with this configuration the performance in light airs was poor, but in fresh winds she was extremely able. The keel design was simplicity itself, with thin fins and rectangular section lead bulbs. The hull was also rectangular in section, by the way. I have never forgotten this design and the fin and ballast shown for Quasar is a development of Logic. There are two principal advantages: (a) The flat sides of the ballast will contribute to lateral HE National Marblehead Championships commenced at an early hour on Saturday morning — a skippers’ meeting at 8.30 am followed by a 9 am start. The OOD, Derek Priestley, stated that as much sailing as possible would be fitted into the weekend, and if time allowed he would start on the second round — although it was highly unlikely that two rounds would be completed. Most competitors agreed with this thought, and would have preferred a slightly later start on Saturday morning; for vin long distance entrants it meant a night of very little sleep. A fairly good wind was blowing during the practising, from under the bridges however. As the wind dropped steadily during the first few heats, starting on the run was a matter of luck in many cases. Skippers faced the prospect of not knowing if their boat would (a) move from the starting buoy, (4) sail in a straight line once started — it was very common to see boats dropping straight into the corner. The finish on the beat was shortened after a couple of boards. By the time the fourth heat had started the wind strengthened, and by heat 5 some of the boats were in second suits. During the afternoon it dropped again and swung slightly. Eleven heats were completed by 6.30 when the wind failed, and any outstanding resails were not taken. Leading boats were Illusion 44R, Anything Goes 43, Sula 41R, Black Rabbit 40R, Axtung 39R, Imagination 39. The skippers of these boats had managed to get them sailing well from the start, whereas some of the others did not seem to be able to find a consistent trim to deal with difficult conditions. There was a Buffet Dance during the evening, which I understand was very enjoyable; some skippers and mates, 466 resistance and improve windward performance. (b) The top face of the ballast will act as a fence on the fin keel. This prevents tip losses and possible generation of a vortex on the end of the fin. This is said to double the effective aspect ratio of the fin and we all know that this must be beneficial. However, it is easy to visualise the increase in resistance of the yacht significantly changed trim when planing or if she bobbed about when going to windward in a chop. Thus the hull form of the canoe body has to be suitable and the form of Quasar should not trim, if past experience is anything to go by. These lightweight A boats have a considerable displacement penalty which severely cuts down the sail area, but as height limits are set for main and jib the net result is a highly efficient high aspect ratio sail plan. The driving force will be by no means reduced pro rata with the drop in sail area. The only comment I can make on the sail plan for this new design is that I have lengthened the luff of the main sail which should improve its effectiveness. I was tempted to bring the boom right down to the deck and thus use the deck as a fence on the main sail. Perhaps someone will try this, as with such a short boom there should not be too much trouble with it dragging in the water when the sheets are eased. With a sail plan like this the sails must be well cut and carefully trimmed, as you cannot afford to lose any driving force and the difference between a good and perfect trim is enormous. Who is going to be first to get this as yet unbuilt design in the water ? I hope correspondence between builders and myself may be started as a designer is quite dependent on a good feed-back from the owners. A new design cannot be guaranteed and no two builders for example get the weight distribution the same. However, Quasar is the amalgam of previously proven ideas, so one offers the design with confidence and I hope it will give a number of people a lot of pleasure. 1976 NATIONAL MARBLEHEAD CHAMPIONSHIPS Report and pictures by Joyce Roberts however, only managed to eat and crawl into bed after a long day’s sailing! Competitors arriving to practise early on Sunday morning discovered that the wind had changed direction overnight. It was now blowing from the far end of the lake, a far easier wind to sail on, as there is less variety in the strength and direction. There was also some rain. Unfortunately for many people, the wind started to drop and vary during the second heat of the day. By heat 14 there was one long leg to windward, and the strength was still dropping, and by heat 16 it was virtually a reach, the wind coming from the hotels, with the inevitable patches of windy and calm areas. This lasted for a few heats, then it straightened up again and came up in strength. It increased rapidly and soon some boats were in third suits. The weather was very cold, and the rain quite frequent. Twenty-one heats were completed by 7 pm and it was decided by the OOD to finish sailing for the day, leaving eight heats on Monday. J/lusion was leading with 784 (after a dead heat on a run with Poppycock) Reflection 78, Axtung 77, M-4-Sis 76, Monopoly 71. Some boats that had gone well on Saturday found beat and run conditions more difficult, and some who had struggled on Saturday were a lot happier sailing on Sunday. The leaders, however, had been consistent on both days.

AUGUST 1976 Contrast in conditions is shown by the winning boat in near-calm (left) and dead-heating with Poppycock (centre). On right is an undere the-weather Mike Harris, who seems jinxed in this class! The start was scheduled for 9.30 on Monday, the time arranged by a majority of the competitors. At 9 am it seemed as if it would be a pleasant day, breezy, warmer and brighter. One solitary competitor was noticeable in a full set of cold weather clothes, including oilskins. This was Mike Harris, who had complained of a chill on Sunday, but was now suffering from what appeared to be a dose of “flu. (In fact it was food poisoning, and Mike had about 10 days in hospital—Ed.) As the day went on he took less and less interest in the race, and after one valiant effort to out-guy Ken Roberts in a drifting beat, just losing on the line, but getting the run, he retired to a car, and his mate from Fleetwood sailed Axtung very well for the rest of the race. Four heats were completed by lunchtime, but the wind was getting less and less, and coming off the hotels. By 1.45 there were only ripples on the lake, and all boats were carrying top suits. Conditions worsened, and when the wind came off the sea it was less than ever. Chris Dicks managed to keep //lusion going well, but other top boats had some trouble, and Walter Jones, who was leading skipper with M-4-Sis before lunch, could not get M-4-Sis to go in the drift. Tom Armour also lost his high position in the last few heats, but Bill Sykes made up a few places. It became obvious to the OOD that with the build up of resails a complete 29 heats would not be possible by 6 pm so the top seven boats sailed the 29th heat against their seven opponents, then the necessary resails were taken. Points were very close indeed, as will be seen from the top seven boats, and the winning per- centage was fairly low for a Marblehead championship, 75 per cent. Reflection and Axtung had to sail off for 3rd position, Dave Latham winning the beat. Once again a National Championship was won by a skipper who sailed consistently throughout a variety of wind strengths and directions. Chris always kept his concentration, and more than ever in the last few heats, he could be seen keeping an eye open for any weather change, as well as watching his opponent’s activities. His rivals from Birkenhead nearly achieved a win, the final two heats proved too difficult for M-4-Sis, not her kind of wind. And once again Dave Latham and Mike Harris were in the hunt, along with Bill Sykes and Tom Armour. There was a newcomer in 8th place, Ashanti, sailed by D. Hollam from Leeds and Bradford. It was pleasing to see two young mates with fathers, Andrew Armitage with Derek Armitage and Mark Dicks with Chris Dicks. As Martin Roberts had his own boat competing he was mostly on the skippers’ bank, but did all the re-trimming on the runs, and set the boat off each beat and run. By the end of the three days all three boys were very tired, but all seemed to enjoy themselves. All the officials worked very hard, and the OOD did well to complete the tournament; a later starting time on Saturday would have cut down the sailing time considerably. The canteen ladies served drinks and refreshments all weekend, to the relief of all competitors and spectators. And as seems to be the way with Marblehead Championships, there were no protests. Results list on page 464. Left, Tom Armour turns Monopoly; he sailed well to place 6th. Centre, Wally Jones holds M-4-S-s to allow Poppycock to clear. Right, not another Dicks? Young Mark poles his father’s winning model. 467