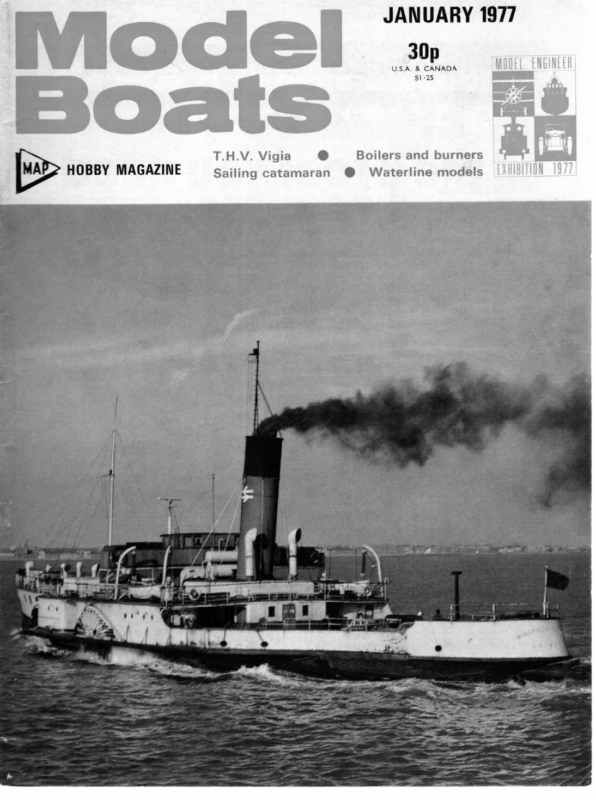

© — __SOp MODEL ENGIN ER af s Bott T.H.V. Vigia & Boilers and burners F3 MADD HOBBY MAGAZINE Sailing catamaran @ Waterline models EXHIBITION 1977 $1-25

JANUARY ADIO control has really given model yachting a boost in France. When I first came down here I was a DIK-DIK ‘loner’, sailing vane, but now there are clubs all along the coast concentrating on R/C. Perhaps R/C sailing appeals to the French character, or could it be that heavy lunches are less conducive to leaping into icy water to stop a planing boat on the run? However, I have found that people who had started their model yachting career with R/C tend to have an admiration for vane steering, and I was surprised to find some who still judge it to be ‘real sailing’. The local club, Carnet Plage, serves the Perpignan area, and model yachting, aeromodelling and model car racing go hand in hand. On ‘field days’ some members participate in a ‘sail in’ in the morning and then switch to flying R/C sailplanes in the afternoon. One even competes in all three activities. At one ‘sail in’ with Toulouse, Beziers and Narbonne, the ‘tramontane’ (our equivalent to the Mistral) produced one of its famous blows, and I waited with interest for the fun and games! The Toulouse chaps had brought one of the typically French long snouted models weighing a little over 12Ibs, plus a Chris Dicks influenced boat, which I was assured displaced barely 11 Ibs! The local boats were in the main chopped off Tinas together with a locally designed yacht familiarly known as the ‘poubelle’ (dustbin). Beziers provided two lightweights of low wetted area. The fun was fast and furious, the lightweights screaming about in showers of spray before diving and/or broaching. Most of the lightweights were caught out ‘over-hatted’ and the old ‘dustbin’ with reefed mainsail and 22Ibs displacement sailed the whole course to win, her fine bow and forward overhang appeared ideal in the prevailing conditions. The designer once gave me a demonstration of her manoeuvrability and seaworthiness by deliberately sailing her in the wake of a full scale motor yacht. Only one competitor was less than happy at the end of the racing: his boat (and radio) had been sent to the bottom after colliding with another yacht. The ‘dustbin’ is not only a heavyweight but sports a lethal dural nosepiece in lieu of a bumper — the owner claiming that this can only possibly be used in self defence! The motivation behind the Dik-Dik design owes much to Larry Goodrich’s fine article published in the Spring of 1975. It was interesting to read the views on R/C ‘design criteria’ by an experienced skipper, but this is not to say that this design and my interpretation of the advice given will meet with his approval. In one article he posed an interesting question — “How would a 46in. waterline 141b hull, which begins to plane in 10mph winds, do against a 20lb full waterline vane conversion around an R/C course in a variety of wind conditions ? One might think of many answers to this question, most beginning with ‘it all depends’, but his implication is clear. A designer is not obliged, under M class rules, to give his boat 50-odd inches on the waterline, it is a choice, and there may, in fact, be a case in R/C racing for sacrificing LWL length to gain in other respects. In his question he stipulates a 14lb hull which begins to plane in 10mph winds. Not every 14lb hull will plane at all and I remember witnessing Ken Roberts’ win in the 1963 M champs at Eastbourne when his Foxtrot, carrying a 70in. rig, planed ‘at the slightest hint of a breeze’. She was carrying more than 14lbs of lead in the keel! Since the introduction of the ‘deep bulb keel’ by Stan Witty, light displacement became the logical development and one wonders how far this development will go — or indeed be allowed to go. So far there seems to be very few penalties, except perhaps that deep draught is not so effective in correcting yaw. A more recent development has been the placing of 1977 An interesting Marblehead designed with radio control in mind by expatriate enthusiast Geoff Draper (A _dik-dik is a small antelope which can weigh between 4 and 15ibs. When alarmed it vanishes in a flash. It has an elongated snout which it wiggles when excited, and is reputed to stay with the same mate for life. How pach of this information is relevant is debatable, but it’s interesting, isn’t it? ‘the mass’ of the yacht further aft and only lip service is paid to Admiral Turner’s metacentric hull balance theory. I say ‘lip service’ because for a hull to be considered balanced it should be balanced at all angles of heel and also it should not rise or fall when heeled. In spite of heavy tumblehome aft, modern designs remain basically unbalanced forms, particularly at low angles of heel. It appears, however, that this state of affairs is acceptable particularly when the yacht is under radio-control. This yacht was designed with these thoughts in mind. The Canoe Body Lightweight, about 14 gallons on the now classic beam dimension of 10in., with a deep draught and the CB pushed further aft. The LWL is 45-6in. — half an inch shorter than that suggested by Larry Goodrich — and the hull is ‘warped- plane’, a form conducive to planing. The admission of even a short overhang enables a much more natural bow to be developed. Both waterlines and level-lines are kept fine whilst the sections in the forebody are veed and flared, providing a progressive augmentation of buoyancy when the bow is depressed; but just as important, dynamic lift is produced — sometimes likened to squeezing a pip between thumb and forefinger. The Appendages With the amazing variety of fin configurations seen these days one tends to wonder why this important feature has not settled down to a more uniform pattern. Is it because it is comparatively easy to modify and thus ‘personalise’ the boat? Somehow, I don’t think Messrs Daniels and Tucker would have approved! They took pains to point out that keel design and sail design were intimately connected. These days, surely, this is a subject for debate. They appeared to be more concerned with the profile of the keel and, referring to sharpie design, write — “‘The plate type of keel is also correct technique, as would be a fin and bulb”. Perhaps one might add that the section of the fin is even more important, as it is this which gives the hydrofoil its character. It would appear that it should resemble a very stable high-speed aerofoil. Can anyone supply some ordinates? On this design I have suggested a slightly thicker section, which should prove more stable than the almost flat-plate types. My experience in sailing with radio control is limited, but I was surprised to find how alert one has to be when

ON s DIK DIK Gesigned by me Vn 6 DRAPER oa , ‘ ‘ 5 : —————— ; { 5 wt copyright of The Model Maker Plans Service 13-35 Bridge Street, Hemel Y a E OPERATION AFTER = — = , 0. = = ” = 4 : st: = oa ae ss WG BACKBONE WIDTH 254m ‘ ; L == = : = NOTE HULL COMES OFF JIG AS ‘ SEMI-MONOCDQUE THE STRONGBACKS REMAN IN JIG — i Hempstead, Herts. oe cet Sores | Pieter a 3 STEM a = | BLO} \ ee — “KH THANSOM -_ ABOUT DATUM LINE = Ww og — = i aa JWG _BacKBoNe MELON Ax AT 20* HEEL \\ WOTE TE MAKE han AFT OF 1 TRANSOMtE*) BOw DATUM Line do or mas ‘ – LEAD ° — . RALLAST aids (wrt SLOT 7 _ 4 | fewest arr nig, \ ACTUAL PROFILE ADOTIONAL LAMINATION Ws hat OM KEEL BETWEEN STEM NO 2 FRED UP WITH KEEL ith Sor 1 Gor ATb, de BEAM Lwi) DRAUGHT 290 = 257 for HOTS ARE MEASURED FROM DECK ALONG TEFLON (LOW FRICTION Disc) SPREADERS RAKED SLIGHTLY AFT METHOD ING (ey MAST LUFF TRACK J RovOUET) ‘HS SIDE SHOWS STRONGBACKS WITH INWALES AND BUTTOCK LINE Som @ 0+ LAMINATED CHINES AND REELSON IN POSTION SECTIONS © NOTE STRONGBACKS TERMINAY TE AT Li? (05°) S89 (27) | A = BACKBONE – I” THICK ae (2) ~ inwaces Wa” s Ya” (2) CHINES a” « Srid’ (2) o HW ni SECTIONS BETWEEN | WATERUINES © (2-7 amooer we ~ KEELSON r enele NOTE THICKNESS OF SKIN 2mm Yar’Rac” May BE USED —— PLY SKINS SHOULD 8 BUTTED ‘AT CHINE JOR THE DRAWING ABOVE INCLUDES SUGGESTED CONSTRUCTION, AN INTERESTING METHOD OF RIGGING A PIVOTING MAST, AND A RANGE OF POSSIBLE RIGS. FULL-SIZE COPIES ARE AVAILABLE, REFERENCE MMI1223, PRICE £1.30 INCLUDING VAT AND POST, FROM MODEL MAKER PLANS SERVICE, PO BOX 35, HEMEL HEMPSTEAD, HERTS HPI IEE. NOTE THAT BODY PLAN AND SHADOWS ARE FULL-SIZE, SHEER AND WATERLINES HALF-SIZE. AFT

JANUARY the yacht is on the run. It is probably my lack of experience, but Chris Dicks also mentions that spade rudders seem to lack control when running or broad reaching, and I have included a small amount of fixed area aft, though this is pure guesswork. The Sail Plan RM competition sailing does not admit leisurely sail the sheet(s) is eased off. A figure of about 25% from the luff was found to be effective. In this version I have divided the area, giving two sails of almost identical surface. As the luffs are of similar length, the ‘slot gap’ between the sails should be effective throughout the ‘span’, and thus is, in effect, a masthead ig. changing, far less carrying different rigs up and down | 1977 the lake, as has occurred in vane-steered racing. Choosing the sail dimensions becomes a matter of philosophy, and knowledge of local conditions would be at a premium. The skipper could arrive at the start with dozens of suits to choose from, but one could argue that this would only increase his chances of being wrong in his initial choice! One thing is certain, if the yacht is capable of being sailed efficiently with a minimum number of suits it will be less of a headache. I have therefore suggested three suits, a high aspect ratioandlower working suit, both of large surface, and a storm suit of about 520sq.ins. for the sort of conditions described earlier. Mast-Aft Rig This rig is not new, and I seem to remember seeing it on an A class design published in the 1930s. The Amateur Yacht Research Society suggest this rig in their study for the ‘ideal yacht’ and one particular version gave such a good performance when fitted to a National dinghy that a patent was taken out for it. It is hardly surprising to learn that the mast is respon- A single halliard serves both sails and it passes over a block at the peak; thus the tension on the sails is equal, and owing to the placing of the pivot point, is close to the aerodynamic axis of the sails, resulting in less twist (or washout). In a gust the luffs should remain in unison and thus the ‘slot-gap’ will remain constant. It is interesting to note that the combined aspect ratio of the sails is higher than on the conventional rig but the combined CE is the same height. With this rig the aerodynamic axis of the sails is sloping and if the sails goosewing the area is balanced about the centreline. This should result in less pressure on the bow, when running, in fact almost a spinnaker effect. It must be stressed that I have not tried out this rig but I feel that it is something to take seriously, even if there is plenty of room for experiment. * * * The suggested method of hull construction shown on the drawing should be quite straightforward and has been used on other models with success. There is the possibility that if stiff ply is used, the bottom panels would need a little coaxing at the bow, since there is gentle two-way curvature; a little heat (hair dryer) would probably suffice, sible for poor airflow over the sail immediately behind it, but when it is stated that a jib set on a wire stay produces anything between 1-7 and twice the drive for the same area —it makes one think! On the other hand Col Bowden’s experiments indicate that the mainsail on a Bermudan Sloop rig can have a beneficial effect on the flow over the foresail and that both sails are interdependent. In the patented back rig all the area is concentrated in one sail set ‘flying’, that is, there is no luff stay. With the sail set flying the pivot point of the boom (or tack fitting) was found to be fairly critical and it is necessary to experiment with this, otherwise the sail(s) will not fly out when otherwise dampening and pinning should do the trick. An alternative 8lb bulb pattern is shown for those who can save weight on the hull or, perhaps, may wish to try it without radio. The drawing also includes details of a pivot mast and associated rigging developed by Mons. J. Rouquet and shown for interest. It requires a mast with a luff groove, either a drawn metal section or a wood mast laminated together to form a track. It is not, of course, essential to the Dik-dik model. OBITUARIES H. K. Corby In Ottawa, last November, model yachting lost its oldest As a highly skilled craftsman engaged in extremely accurate scientific work, Kenneth Corby had no equal. He was incredibly meticulous, everything had to be ‘spot on’ and he could not bear the sight of poor workmanship or finish. The right tools had to be used for the job in hand, he would not attempt it otherwise and, to him, using a pair of pliers on a nut was a sin! His fittings were light but very strong, and were perfect examples of the metalworker’s craft. He was one of the earliest members of the YM6mOA at Hampton Court, formed in 1926 and the original home surviving member when Kenneth Corby passed. peacefully away at the ripe old age of 93. He had emigrated to Canada after his wife died about ten years ago and lived with his son. There can be few model yachtsmen who remember him personally, but those who were active in the fifties will link his name with his vane gears and fittings and there must be quite a few still in use and treasured by their owners. In fact, he was still making one or two gears at the age of 91 and at least one was sent over here. Kenneth Corby was an instrument maker with the National Physical Laboratory, Teddington, and was never happier than when he worked at his bench. Consequently, he had a fully equipped workshop at home, where he built several ‘A’ Class models, some of which are still remembered to this day. His first boat was Conquest, with which he finished runner-up to the famous Bill Daniels in a pre-war Championship. Then followed Concord and his last boat, Condor, which is still sailing. He also built for other owners, Barika and Actinia just before the war, both designed by Admiral Turner, and Sharma just after the war, to a design by the great Charles Nicholson. She was owned. by the late Guy Blogg, one of model yachting’s most eccentric characters, a deep thinker and a brilliant mathematician. of the ‘A’ Class, and was elected a Vice-President of the Club after the war. He was the last of the old school of model yachtsmen, the like of which we shall never see again, and his death marks the passing of an era. To his only son, John and his family, we extend our deep sympathy.—N.D.H. J. W. Metcalf Another model yachtsman well known for his fittings died recently — John Metcalf, who was International Racing Secretary of the MYA for a period about 20 years ago. Although he had not been active in model yachting for some seasons, he used regularly to visit the A Championships to renew old friendships, and will be well remembered by older enthusiasts. 25

MODEL BOATS LTHOUGH there is no established class for multihulls, they can be exceptionally fast and are great fun to sail. The extra speed comes largely from a reduction of weight, due to the absence of ballast. The model to be described was designed to comply with the following requirements — _ 1. Light weight and simple construction. 2. Quick, inexpensive and easy to build. 3. Easily dismantled into three separate hulls, mast, sails etc for transportation. 4. As much speed as possible. 5. Minimum chance of capsizing. 6. Easily controlled sail area to suit wind conditions. 7. Centre of lateral resistance easily adjusted to compensate for sail changes and allow the boat to be adjusted for sailing on and off the wind. 8. Good directional stability in the absence of wind-vane steering and/or radio control. Scale of these general layout drawings is approximately 1/10 full size. Weight of completed model approx. 7ibs. 32

JANUARY 1977 A Simple 48 in. Trimartn This model uses expanded polystyrene for the hulls and gives exciting performance By C. E. Heath Design at high speeds. The centre of buoyancy of the floats also The following parameters had to be optimised — all-up _ needs to be well forward for the same reason. weight, hull shapes, beam, mast height, sail area, centre Centre of lateral resistance is controlled primarily by of effort (CE) and centre of Jateral resistance (CLR) the positioning of the keels and adjusted in use by the Too little weight could result ina model which capsized __ vertical positioning of the rudder. This is the main purpose easily whereas too much could spoil the performance of the rudder, apart from its effect in improving directional With polystyrene as the main building material, the deck stability. The latter point is dubious anyway, as multi thickness largely controls the all-up weight. hulls always possess good directional stability, which can Hull shapes must, of course, be slim and smooth become excessive unless keel lines are adequately flowing. The fioats, however, need bow sections as gener‘rockered’. Assuming radio and/or wind vane steering is ous as possible to avoid burying of the bow of the lee float not added, the rudder is not permitted to turn at all. 33

MODEL BOATS A tall mast gives high aspect-ratio sails which are most efficient to windward, but increase the risk of capsize. Since windward performance is not vitally important in a non-racing model, the mast height is only moderate. Increasing beam should bring increasing stability and higher speeds, with theoretically no disadvantage for a model trimaran. In a full size one, structural problems would increase. Excessive beam, however, could result in an unrealistic model, and the beam was limited by aesthetic considerations. The optimisation of these parameters was achieved in three ways: (1) from experience of a full-size trimaran of 30ft overall; (2) intuitively; and (3) by varying some parameters on initial trials, the main ones being beam and sail area. Faulty design could lead to any or all of the following — directional instability, easy capsize, burying of lee float (or bow of lee float), pitch-poling or tripping, failure to achieve high speeds. The model being described appears to have avoided these faults. Construction Polystyrene foam was selected for the hulls and a suitable 4ft plank was purchased. Cutting and shaping the polystyrene is best done with a length of resistance wire, heated by a car battery or any low voltage supply. With this method, suitable ply templates should be cut in pairs and used to guide the hot wire through the polystyrene plank. This is done in three stages; plan, elevation, and cross-section in that order, the Jatter being the most difficult. The hull shapes are all of the hard-chine type with V bottom to minimise the compound curves. The material may alternatively be sawn and/or sanded but this, of course, tends to leave a rough and porous finish. Whether this will matter depends on the method adopted for obtaining a final finish. There are three alternative ways in which the polystyrene may be finished — (a) Covering with Solarfilm, using an electric iron at a very low temperature in the usual manner. This method is quick, but can become rather awkward at certain points where compound curves are involved. (b) Veneering with ~;in medium balsa sheet. This cannot be done over compound curve areas, but should be quite successful on the ‘top-sides’ above the chines. This is the area which shows most and benefits from the good finish obtainable. (c) Painting the polystyrene directly. Suitable compatible paints must be used of course, and the polystyrene must have been cut by the hot-wire method. This would be the ideal way of dealing with the compound curves underneath the hulls. The hulls must be slotted on top to receive the two beams, which are wooden dowels These slots are cut oversize, then reinforced with ‘Woodfiex’ and finally shaped with a round file. Decks are cut from }in plywood, exterior quality and oversize about tin all round to provide a protective rubbing strake. The decks are glued to the hulls with ‘Evo-stik Resin W’ and provide a sound basis for all fittings. The deck/hull joints should be sealed. Silicone rubber is best and very quick, but rather expensive. Simulated planking on the decks looks excellent (use a black ball-point) and at least three coats of varnish. The mast is a solid dowel, tapered by sanding the top one third and stepped directly into a very strong deckmounted socket. Standing rigging consists of forestay and backstay only, counter-tensioned. This enables the foresail to be set up ‘hard’, giving a good straight luff, essential for efficient sailing. No shrouds are necessary, provided the mast is a good tight fit in its socket. Sails are conventional, except that a set of three foresails is desirable to control the total sail area to suit conditions. Sheeting points must be efficiently located. The mainsail is generously battened to provide an efficient shape and is boomed with a wooden dowel. Mainsail battens are of thin ply, varnished and glued in place with epoxy glue. Lateral resistance is provided with low aspect-ratio keels and on all three hulls which also protect the hulls from damage at a vulnerable point. The keels are of tin marine ply, recessed into slots and faired in with Woodflex. A slotted batten should be recessed into the stern and faired in with Woodflex, and the high aspect-ratio rudder of tin ply should be a good tight fit in the slot. A cabin of any pleasing shape can readily be built up with din balsa sheet. The hulls are connected by two beams (dowels) and these are retained with split pins through holes in the deck and beam, allowing the three hulls to be readily dismantled. Handling The first and obvious point here is that the boat can and will capsize if overdriven. On the other hand, the speed will be disappointing if one reduces canvas too far. A compromise must be arrived at, depending on how adventurous the owner feels and whether he has a pair of waders handy! In practice this compromise is not difficult to arrive at providing the model has two or three alternative headsails and providing conditions are not excessively gusty. A good steady breeze is definitely desirable for the first trial sails. The second point to be clearly understood is the function of the rudder, which does not turn but is set at various depths to control the CLR. Its setting, however, is not critical. A large headsail will move the centre of effort forward and the CLR should be moved forward also by raising the rudder. This keeps the boat sailing on a given heading in relation to the wind. To sail on a broad reach, lower the rudder and slacken sheets well off. For close-hauled sailing, harden all sheets and raise the rudder appropriately. Speed will be somewhat reduced and overturning moment increased, but progress to windward is always rewarding. Reaching is a good compromise which allows the boat to be sailed from A to B, turned by an assistant and returned from B to A with a minimum of fuss. Maximum speeds are also likely to be reached. FAST ELECTRICS (continued from page 31) speed a ducking!) The basic idea is to complete as many of the hazards in three minutes as possible, and at present the unofficial record stands at 60 points, achieved by Jan Podlaski of the Manchester club with his petrol boat. This course is very popular among Northern clubs, Manchester and Birkenhead in particular. Although not as difficult as F3, it has instilled interest anew in R/C steering, putting back into steering what the new F3 course may have taken away. Hopefully it will increase the numbers attending area and national finals. The next point which would involve electrics was Frank Bradbury’s proposal for the introduction into national events of a speed steering course based on the cloverleaf F2, to be run with the present F3 course. For those not familiar with this type of course (it has its origins in the north) I shall explain. As can be seen in Figure 1, the course is F2 but the driver follows the pattern of a cloverleaf, completing each set of hazards with no penalty for a touch (although a touch can produce its own penalty, at 34

JANUARY Readers Write…. WHERE DOES THE C. of E, GO? Dear Sir, Ever heard about the C of E? No, not that, you know, that nonsense about centre of effort on sails. Well, let me tell you that they’ve got it all wrong . . . must have been looking at the wrong end of their slide rules or something. You see, in my opinion, finding the centre of effort of a sail and placing it in a fixed position on a boat is rather like placing the boat in the pond when it’s been emptied for cleaning out. You might as well not bother, unless you first look carefully into what a sail actually does. If we forget about aerofoil sections and slot effects and such things for a bit, and look carefully at the simple fact that a sail creates energy and transmits it through stays and/or mast which pushes the craft along, and if we recognise that the more the mast leans over, the greater the turning moment trying to thrust the boat ina circle in the other direction, then we’ll all start getting somewhere. I know that it all sounds a bit hoity toity, but read on and you’! see what I mean. This tendency of the mast to ‘twist’ the boat to windward is what we call weather helm, and it is also the cause of the dreaded ‘broach’. If you grab your magin one hand and a boat with a mast in the other, and find somewhere to float it, we’ll do a simple demonstration. With all sails removed, allow the boat to float upright in the water. Now push it gently along with a finger from behind, andif the rudder is straight, it will go straight. Now apply the slightest pressure with your finger behind and slightly to one side of the mast, and it will begin to steer in the opposite direction to that in which it is heeling. The greater the heel on the boat, the greater the capstan effect. In a broach, the craft is overpowered and heels. This begins a chain reaction, the craft is capstaned up wind slightly, heeling further as it “comes upon the wind’, helped to heel further by slight centrifugal force, maybe. Since it has heeled further, the effect begins to increase, and so on, until the boat has swept round in a great arc and comes upright, we hope, face to wind. After some experiments with a Una rigged 36R which carried the most tremendous lee helm (the tendency to fall off the wind), it was found that even this wanted to revert to weather helm ten- dencies when sharply heeled in a squall. Further to this, it was noted that a cutter rigged vessel just flying a jib at the end of a long bowsprit actually swept up wind in a squall as well. Now someone try and tell me that they’ve got a perfectly balanced boat! (The Revenue cutters of the eighteenth century carried a bowsprit four-fifths the length of their hull in order that they could remain to let that old mast take the submarining effect out of the squalls whilst catching all the power of them (when the mast straightens , the boat will be pushed forward) plus the benefit that you won’t waste quite as much energy waggling your flipping rudders about! Worried about anything? Right, if the boat is running downwind and rolling, she’ll be swinging in the opposite direction to the roll. It doesn’t matter whether she’s running or beating, that mast is creating the weather helm tendencies just the same, since the mast is always pushing forward when sailing. Hoping that a few of you will kick the idea about, and assuring you that I’ll have a go as soon as I can. Rainham P. Whitehead STEAM CONTROL Dear Sir, I notice that in the July issue of Model Boats Jim King remarks on the lack of radio controlled steam driven models and goes on to say that a plant that needs little attention is an absolute essential. I wholeheartedly agree with him, but surely his ‘balanced boiler’ is a complicated way of ensuring a fairly constant water level in the boiler? As a steam boat man for more than 20 years I have found that the old fashioned by-pass valve is perfectly adequate, with two conditions. Firstly, the valve itself should be a plug cock, not a screw-down needle valve. The latter always seems to suffer from silting up problems, which alter the amount of waste being bypassed, but the old plug cock keeps relatively clear, due no doubt to the different shape of the aperture. Secondly, a small bore outlet will give a definite jet of water and its length from the boat’s side is a good guide to the amount of water being put overboard. Together, these two will keep the water level within small limits for a reasonable time, particularly after the steam needs of the engine have been ascertained. A boiler with a water capacity slightly higher than necessary also helps considerably, as a slight difference in water feed has little effect. The ultimate answer is probably a pump whose stroke and therefore output can be varied whilst running. If the clearance be- tween pump and cylinder rod can be kept to a constant minimum, no matter what the stroke, air bubble difficulties are eliminated. The sketch illustrates such a device which has worked for me for about 18 years with no trouble. The pump is driven from the top of a slotted bar, pivoted at its bottom end. The lever is moved by an eccentric through a connecting rod to a die block in the slot. The radius of the slot is its distance from the handleable with their huge drivers, exerting forces far to one side of the craft). Right, there’s the problem. Now what abont some form of correction? Bowsprits would seem to be out on racing craft at any rate, with one or two exceptions, and as pointed OPERATING KNOB eae out earlier, excessive lee helm is only tem- porary, and has inherent steering problems of its own in calm weather conditions. So what about somebody (finish your mag first) getting in their workshop and creating the articulated mast? (I can’t — got home problems and building societies ete on my mind). Let’s see a few masts next year which lean forward in the ‘blows’, and return to their normal positions afterwards. Look — you racing fiends have all got tall masts, and that makes the problem worse — more leverage — so if you are a radio racer, waste a pound or twofon another motor system so that you can adjust your mast for the wind on the day, and you’ll be able to carry a little more sail with control than the other blokes. If you are a freesailer, a springy backstay or something, BRACKET i SCREWED BLOCK SCREWED ROD 1977 eccentric shaft and the length of the con rod is that radius plus the throw of the eccentric. The die block is held by a pair. of lifting links pivoted to a block screwing up or down a rod, turned by a knob at the top. It will be seen that with the die block at the top of the slot the pump stroke almost equals the eccentric throw. As the block is lowered the stroke of the pump increases but the rod clearance remains the same. As the control mechanism is a screw (say about 2BA) a very fine adjustment is possible. I find that even after an hour’s run the water level in the boiler is still the same. The actual sizes are subject to experiment but I would suggest that a Zin. x Zin, engine probably needs a ¥;in. diameter pump with #in. stroke running at about one-fifth engine speed. The mechanism should, therefore, be designed to give a stroke variable from about ¥in. upwards. A by-pass is fitted but this is only used during the warming up process, the plant running with it shut. It has been my experience thet once set the pump can be forgotten as can the boiler water level. A comforting thought after a long run with the ‘steam radio”! © Newcastle Upon Tyne W. J. Hutchinson R/C LICENCES ESSENTIAL Dear Sir, : ‘ As most R/C modellers will know there is growing pressure from manufacturers of walkie talkie radio sets for their use to be legalised in the UK. They operate in the 27 Mhz band, currently used by radio modellers. If the band is given to CB sets, or shared with them, we face at best an expensive transfer to a different band, at worst the loss of any band to call our own. The SMAE are already taking this up with the Post Office and I hope that the MPBA and the MYA will join them pressing very strongly for the 27 Mhz band to be retained for model control What can the individual do? He can ensure only. that his radio licence is up to date, or (if he is operating illegally) he should get a licence. Not just because it is illegal to operate without one, but because the best argument for the retention of the 27 Mhz band is the number of modellers who will face problems and expense if they have to move to another space in the radio spectrum. How do the Post Office judge how many of us there are? They count the number of current licences. So you know what to do. Danson MYC R. R. Potts FACILITY DEVELOPMENT Dear Sir, ’ : TO ALL modellers in Lancashire, Cheshire, Liverpool and Manchester, I have for the last few years sat on the Federation of the North West Sports Association, where I have actively pursued increasing our water and flying areas, with at present a few limited successes. This body of people who meet under the Sports Council have done a tremendous amount of ground work in establishing contacts with all planning authorities etc that they are now approached before any work is carried out on any recreational development. This allows the Federation to draw upon all its expertise to formulate a detailed plan for the development to proceed. This sounds a bit far fetched, but I can assure you it works. Recently, under a directive from the Minister of Sport the Regional Sports Councils have been reformed and reorganised. I have been elected to serve on this new Council as one of the nine representatives TO PUMP CS PATH OF ECCENTRIC of outdoor recreation (approx 120 organisations), where, I hope, I can further modelling in the North West. I chose the word ‘modelling’ so as to cover all models, although I sit on the Federation through being the Vice-Chairman of the NWA SMAEI consider it my duty to protect and improve the interests of a// modellers — MPBA, BARCS, NMPRA, MYA etc. My own interests are varied as fellow members (continued opposite)

MODEL BOATS KRISPIE Part Two of our 36in yacht made from inexpensive materials, the subject of our Christmas free plan. It appears to have stirred a great deal of interest in cornflakes… WE left our model ‘in frame’, last month, with a brief note on planking the first layer with card strips; perhaps it would be helpful to expanda little on the plank- ing aspect. Firstly, the material, which is cereal packet card. From what we have seen, there is little difference in thicknesses ete between various cereal packets and most will therefore be suitable. There could be the odd one in rather de luxe card, and though the thicknes s is not too crucial (as long as the finished hull beam does not exceed 9ins) thicker card is likely to be heavier. Judging from our experience, you will need not fewer than five of the large size cartons, which for cornflakes means 500g size, or the equivalent. As already mentioned, about 10ins is the longest required, and we recommend cutting the strips from the flat front and back panels plus the sides, discarding the top and bottom and any creased area. Strips should be no wider than gin (16mm, say, as it’s metric year!) and could with advantage be narrower. However, even at 3in each layer requires about 88 strips, so how much narrower you make them depends on your Own assessment of your patience! One thing you will note as you proceed is that if you use all parallel strips and start at about 45 degrees, the strips will gradually fall towards the horizon tal as you near the stern, and become more vertical towards the bow. This offers no problems, and is mention ed only in case a builder wonders if he’s gone wrong. It is well worth fitting scrap fillet stri ps along the knuckle pieces (see photo) to provide a positive position for the ends of the planks terminating against the underside of the knuckle. The narrow space between knuckle and inwale can have the planks just glued in place, overlapping top and bottom and trimmed at a later stage. The planks will be found to lie well over most of the hull but will want to twist slightly when they reach the inwale. Care should be taken to get them lying snugly, or the second layer may come out unevenly, and although this will not materially affect the sailing qualitie s of the model, it is the part of the hull which shows most when the yacht is completed. Similarly, in relief at reaching either end, or impatience to get on with the second layer, don’t let the planking get untidy towards the bow and stern. The card can be pre-shaped in the fingers to sit fairly on the end bulwarks, nos. 4 and 8; the planks are of course glued to these end ones but not to those between. As each plank is measured and marked, check that the end will cover the wood of the inwale but snip it off so that it does not overhang too far: it may be a help in one or two spots to be able to get a finger underneath during the next stage, and anyway too much waste overhanging can confuse the necessary plank lengths for the second layer. Check carefully that all the first planks are snug, and adjust or replace any not up to scratch. The second layer can then be started, laid at about 45 degrees in the opposite direction and again starting in about the middle and Planking the first layer towards the bow; the fillet strip glued on the underside of the knuckle (the upper side in the picture, as we’re working upside down) is just a piece of scrap balsa providing a positive Positioning for the planks. Note that the planking appears very slightly loose. This smooths out with the second layer; if it was tight it would make a hard angle over each stringer and lose the smooth curves of the hull. working each way towards the ends. Cut and fit the first pair and lightly pencil their positions on the hull. Now apply contact cement thinly over the pencille d area and to the backs of the two planks. Allow to dry — ten minutes or so — then position the keel end of one and smooth it gently down, ensuring it makes contact with each of the planks of the first layer. Repeat on the other side. Each further pair of planks is now added (there is no need to pencil their positions, of course) making sure that their edges fit closely to the adjoining plank. Laying a plank in place dry, to mark it off, will indicate if any difficulty is likely, when adjustment can be made, either by using a tapered plank or two narrower ones, or even tapering just a part of the plank. In general, however, no difficulty should be experienced in getting a fair surface with no gaps. Work along to each end as before, and don’t be tempted to rush. Keep the keel ends making a straight line down the centre and the planks in contact all the way. A few planks a day will mean better work and a nicer hull, and since the material is cost-free anyway, don’t use any ragged or out-of-straight plank, When planking is completed, leave the hull to dry out completely, at least 24 hours, and conside r what sort of paint you will use. The best finish to use would be epoxy paint, but if we are trying to keep the cost down polyurethane would be more economical. Ordinary gloss paint is acceptable, but cellulose is a little thin. It is necessary to consider the finish at this time because the next step is to soak the card with a thin but generous coat of an appropriate base. Clear dope, with a drop of castor oil per ounce of dope to plastici se it slightly. or cellulose sanding sealer would be safe for any finish, including epoxy; for this last Humbrol have a wood filler which would be good. Most polyure thanes suggest using thinned coats of the finish itself as priming and undercoat, while with oil paints a good soaking with shellac is an excellent base. Clear dope, by the way, is also suitable if you propose to use a glass fibre/polyester resin finish, Having made your choice, paint a thoroug h coat on to the hull so far and leave to dry complet ely. With the

JANUARY second planking layer, the card stiffens up quite a bit, and once soaked with one of the bases suggested it becomes stiffer still and, more importantly, any little ragged edges become rigid and ripe for removal with a gentle rub over with fine glasspaper. The increased stiffness also makes trimming overlapping edges simpler; at the present stage this only matters at the bow, since the next step is to block in and shape this area. If in balsa was used for the main keel member, there will be enough scrap left over from this to laminate with vertical slices from the keel outwards below the knuckle, and horizontal slices above the knuckle. The stringers etc must be trimmed. off flush with bulkhead $ to do this, and the hull will have to be eased off the building board to do the above-knuckle region. Sliding a long knifeblade under each shadow should free it easily. The bow block laminations should be sanded carefully to shape, handling the hull fairly gently as it is not yet at full strength. Paint some more of the chosen base over the balsa, dry, and re-sand as necessary to smooth it. Trim along the inwales and knuckle edges and lightly sand. Check the interior of the hull for any separation of the inside planking, but be careful if pressing into place not to produce an unwanted bulge on the exterior. Leave the shadows in place for the moment, but slice off the projecting tops so that everything is at deck level. Now comes the covering stage. The de luxe way is to use -60z ‘loomstate’ glass fibre cloth, which may be induced to cover the entire hull in one piece or, at worst, two pieces joined along the keel line. This is simply stretched over the hull and pinned, then epoxy paint is brushed through its weave. When dry, one or more additional coats can be applied, or if the glass is well secured with the first coat, later applications can wait until the fin and deck are in place. However, on the economy line, a similar effect can be produced by obtaining a pair of ladies’ nylon tights, about 15 denier mesh runproof (we are assured) with one leg undamaged. This is simply drawn over the hull and any slack taken up above deck level, pins round the inwale holding it temporarily while thin paint (polyurethane or oil undercoat) is flowed over the hull exterior area. At the bow it will be necessary to slit the nylon with a razor blade and overlap the resulting tabs to cover the balsa block, painting them down thoroughly and going back as the paint starts to dry to rub down any curling edges, using a pad of scrap from the waste part of the tights. Again leave to dry completely, two or three days at least, more if it’s left in a cold shed, then go over it carefully to ensure that the nylon is truly stuck down all over. When satisfied, trim the surplus nylon away round the gunwale, lightly rub down, and apply another coat. Another decision is now required. You can havea flat deck, which follows the sheerline and looks so-so, or a cambered deck can be fitted, which lookes much more attractive and is not really more difficult. It just means that the deck beams have to be shaped before installing them, and since we are now going to need a couple, the decision to camber or not has to be made now. Only two beams — say numbers 3 and 5 — are needed at this point since they will be enough to hold the hull in shape and any more would get in the way of interior work in the hull. Check before fitting them that the maximum beam of the hull does not exceed Yins, ideally by laying the hull upside down ona flat surface and having a helper hold. two set-squares (books could do at a pinch) one each side. Measure the distance between the verticals The first plank layer at the stern, The seventh and eighth planks forward have a bulge where they have not sat smoothly down, and any instance of this requires attention or a cockled second layer could result. 1977 and if it’s just under 9ins well and good. If not, it is possible to shorten the deck beams by a whisker to pull the sides in, without, it is hoped, too much alteration to the overall shape. If you don’t want to register the yacht this is not too important, incidentally. A fairly easily available, easily worked and light timber for these deck beams is a planed lath, which can be bought at most timber places, but they can be cut from spruce sheet from your model shop, or ply could be used. Glue the two first ones in, and then remove the shadows. These should twist out or tap towards the wider direction, but take care that no glue has secured them to the card planking. The interior now needs a liberal coat of the same base as used on the exterior, having first made sure that no planks have sprung to leave a gap between the two layers of card. If there is a bulge inside it can be cured by cutting across it, squeezing some glue in, and gently smoothing down, making sure that no strain is put on the outside layer. It is well worth covering the interior between the stringers with strips of tissue (paper handkerchiefs would do) so that after two or three coats of ‘base’ a coat of gloss paint or varnish will provide a relatively smooth and waterproof interior surface. Since we are dealing with card, albeit well impregnated with dope, shellac, polyurethane or whatever, any water trapped in a pocket somewhere is bound to lead to a weak spot in the hull. Go over it all carefully to ensure that everything is well sealed inside and out. The next step is to mark carefully the position of the fin and to drill a series of holes through the main keel member as a preliminary to cutting a slot to pass the ply fin. It will be necessary therefore to obtain the piece of ply for the fin so that the slot can be an exact fit; there isn’t a great deal of material left each side of the keel if you have used 2in balsa and have to pass a } or -#;in fin through it, but this is actually a help in producing an accurate slot and therefore a truly vertical fin. Marine ply is not essential for the fin, exterior grade being quite adequate and much easier to come by. If a boat is left afloat for months, as in full-size, then marine quality must be used, but for our purposes the ‘water and boil-proof’ specification is more than we need. Provided it is thoroughly painted or varnished, exterior grade is perfectly suitable. The size of the piece required is 10in x 5tin if it is to finish flush with the top of the centre deck stringer, or say 1dins longer if it is to be brought through the deck and shaped into a handle. An alternative would be to screw a handle into it from above deck. Make your decision and cut the fin to shape accordingly; mark on it the line of the hull and the line of the lead and shape the area between to the cross-section shown. (to be continued)