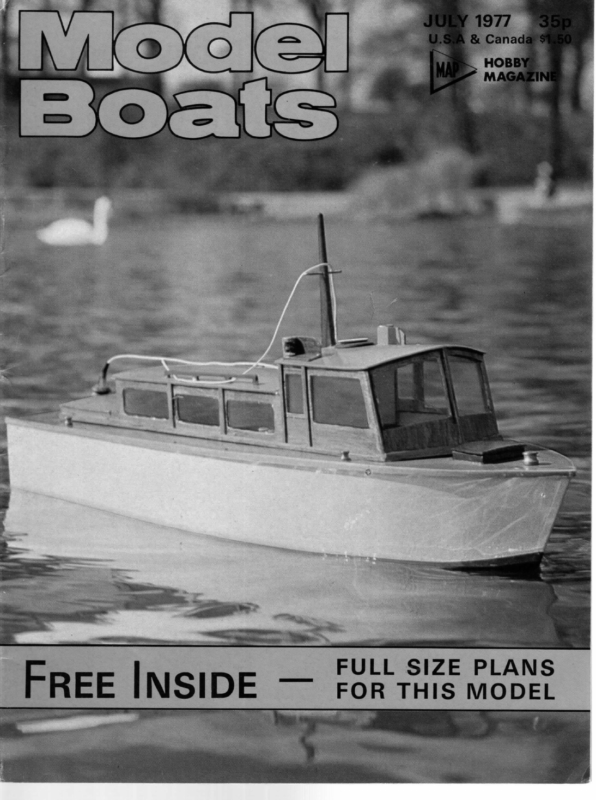

FULL SIZE PLANS FREE INSIDE — for THIS MODEL

SOME ASPECTS OF DRAG MODEL YACHTS The 10-rater class offers greatest freedom for experiment in hull design, so affecting drag. Vagabond, by P. Rickett, tried this long 75in. L.W.L., in 1972, but with little success. OWARDS the end of the 1976 sailing season at Poole, we sailed a few races with boats and skippers inter- changed and from this, interesting data emerged. Known good skippers were still able to achieve considerable success with boats hitherto averaging very low scores, whilst skippers who usually averaged lower scores, could do no better when sailing the known good boats. The inference of course, is that in RC sailing at least, the end result is more attributable to the skill of the skipper than to the design of the boat. This is not to say that boat designs are unimportant, since a prerequisite for success is the use of a design based on sound principles and experience. Having said that, it is worth looking at some of the factors which may affect the performance of a yacht, which are not usually covered in building instructions or rules, and one of the most significant factors is that of drag. The following information has been gleaned from several sources and is generally non-mathematical, one of the objects being to produce information frequently avail- able for full size yachts, but rarely, if at all, found specifically for model yachts. By definition, drag is the resistance force to a motion in a fluid acting in a direction opposing that motion, and for all practical purposes associated with yachting, drag is most unwelcome. Positive exceptions, of course, are in the use of sails whilst on a run, particularly the spinnaker. by Trevor Reece It is first necessary to examine the flow conditions on a surface to appreciate the cause of skin drag and the ways and means of reducing both this and form drag. Figure 1 shows the flow lines adjacent to the surface of a thin flat plate at zero incidence angle to the direction of the motion. At low velocities or at points near to the leading edge, the flow lines are quite uniform and the gradient of velocity is very close to the surface. At higher velocities or at distances further from the leading edge, the layer of flow lines thickens, but still remains relatively thin until a transition to a different state occurs. This transition results from instabilities being set up which cannot be suppressed or damped out by the viscosity of the fluid, and in practice may be initiated by surface roughness, curvature of the body surface and inherent turbulence in the fluid stream. The thinner layer is referred to as the laminar boundary layer and the thicker layer as the turbulent boundary layer, typically eight to ten times thicker. The laminar boundary layer produces appreciably less drag and consequently the point of transition to the turbulent layer needs to be delayed aft as far as possible for a minimum drag condition to be achieved. From the turbulent layer, energy is dissipated in the form of momentum exchange to the surface, and in the form of turbulence and wasted energy flowing downstream. | | The main elements of drag with which we are concerned are those arising from the movement through air of, above water components, including sails, decking and rigging and those arising from the movement through water, of the components below waterline, eg, hull, fin, rudder and compared to skin and form drag. At this stage it is convenient to dwell on the latter forms first, since it is only in this area that skippers can do anything to reduce drag; wave drag is more a function of the hull lines and thus for any one design, nothing can be done. _LAMINER TURBULENT BOUNDARY eee BOUNDARY =—— | LAYER LAYER |LEADING FLOW LINES ON SURFACE OF FLAT PLATE AT ZERO INCIDENCE TO FLUID STREAM |EDGE ‘ FIG.1. l skeg. As a further generalisation, drag from either source can be resolved into that caused by the gradient of fluid near the surface of the body (hull or sail), usually called ‘skin-drag’, and that caused by failure of the fluid streams (water or air), to unite after being pushed apart by the body and called ‘form drag’, the latter usually resulting from the turbulent wake of energy left downstream. A third type of energy results from the surface waves made by hulls and this is relatively insignificant at low speeds IN f =p, TRANSITION What we are primarily concerned with now, is the thickness of the laminar boundary relative to the surface roughness, and the position of the transition to the turbulent layer. Both parameters are a function of length from the leading edge and velocity of fluid, and are conveniently framed within a dimensionless number known as the Reynolds number*, given by R = V1 where V = velocity Vv in ft/sec, 1 =length from leading edge in feet and v = kinematic viscosity, being a constant for any one fluid at a specified temperature. Table 1 lists the Reynolds numbers 370

JULY 1977 V (knots) A; V (ft/sec) haga) 2) 24245 3 | 4 Ole). 8 =| 104) be done to prevent any projections which may initiate a transition to a turbulent flow. This includes surface 12 roughness and, in the case of sails, attention to mast 169 | 2-53 | 3:38] 4:23 | 5-07) 6-76/ 10-14) 1352/169 | 203 Uinches)3 | -3 | 5 | -7 | -8 | 10} 6] -7 | 10} 13 | 17 | 20} 9410 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 3:0} 12 | 13 | 20} 24 26) 33) 40} |26 | 40 | 53 | 66) 80} 13] 20] 4-0} x105 26 | 40/53 | 66 | 80} x105 40] 26 | 3:3] 60 | 80 53 | 80 106 |158 }10-:0 |11-9 |—-+— }106 |13-2 |15-8 | + {21-1 |264 |31:7 |—+—- 36 | 40 | 6:0} 80 }10-0 /11-9 | 15:8 | 238 | 317 |396 |47:5 48 | 53 | 80 }106 |13-2 |15°8 | 21-1 | 31-7 |422 |527 |63:3 }10-0 | 13-2 |16-5 |19’8 | 26:4 |395 |527 |660 | 79-0 60 | 66 fittings and rigging. (b) It is very desirable to maintain a laminar flow for as great a distance as possible along the length of a surface and as an aid to this, very great attention is re- quired to those parts of the surface which curve away from a laminar boundary layer, for example, at points aft of the maximum LWL beam. Hence additional polishing and rubbing down should be concentrated over the stern sections rather than the bow. With this in mind, it is useful to determine the critical eG He a roughness given by the formula 100v TABLE 1. REYNOLDS Nos. FOR SALT WATER: Ri=VL Kerit which apply to lengths and velocities typically found in model yachts, but extended in terms of velocity to cover planing speeds. The transition region is extremely variable in position but broadly occurs with Reynolds numbers from 5 x 10° to 5x 10*, a figure of 10° being typical and this area is emphasised by the block lines shown in the table. From this, it is apparent that for all fins, rudders and some model hulls, laminar flow can be possible over their entire length at the highest speed of 1-2 “ LWL knots. Hulls of 50in. LWL or more may well have a higher skin drag because of the production of turbulent boundary layers somewhere aft of the maximum LWL beam, when sailing at the highest speed. Vinknots | 1 | 12| V.in ft/sec WATER AIR 2 | 22) 3 | 4 | 6) 8 | 10 169| 253) 3:38) 4-23) 5-07) 6-76/1014 | 13:52) 16-9 89 | 59144 | 35 | 29 | 22 | 1:5.) 1124) 7571-56 TABLE 3 |..45 437.428.) 1:1 | 09 495114, | Aa CRITICAL ROUGHNESS IN THOUS. The resulting critical roughness for appropriate velocities is given in Table 3, there being no practical difference for salt or fresh water. For a typical RA or RIOR yacht of 55 | 60 Ry=1×105 | 113 | 227 | 342 |-380 | -427 |-474 |-522 |-569 4×105 |-057 | 114 | 171 | 190 |-213 | 237 |-260 |:285 8×105 |-040 | 080} 121 | 134 |-151 | 168} 55in. LWL, the maximum speed of 1-2 /LWL = 2:57 184 |-201 1×10& | -036 | -072 | -108 | -120 |-135 |-150 |-165 |-180 2×10® | -025 | -051 | 076 | 085 | -096 | 106 |-018 |-117 |-127 |-036 | -054] -060/ -067 | -075 |:083 |-090 TABLE 2. LAMINAR FLOW THICKNESS IN INCHES (Salt Water) S=31//Ri The thickness of the laminar boundary layer for various Reynolds numbers is given in Table 2, which shows quite clearly how the layer builds up as the distance increases from the leading edge. The other important factor is that with higher velocities (R. Nos), the layer becomes thinner at any one point on the surface and hence the roughness of the skin attains greater significance. Below a laminar boundary layer, the surface roughness either does not appear to have any effect because the disturbances are damped out by the stream, or a transition to a turbulent boundary layer occurs, greatly increasing the skin drag. Current thinking concerning the turbulent boundary layer is that immediately next to the surface is a thin laminar flow layer which decreases in thickness as 1 or V increases. If the skin roughness penetrates the laminar sub-layer, the drag will increase and therefore a smaller roughness will produce more drag as R1 increases and in fact, the drag force becomes proportional to V°. The overall conclusions to be drawn from the foregoing are two fold: (a) with V = velocity in feet per sec. and Kerit in inches. (Note — 1 knot = 1-15mph = 1-69ft/sec.) K cRIT.= 100 LUlinches) | 12 | 24 | 36 | 40 | 45 | 50] 4×10® ; Vv salt water =0-015/V fresh water = 0-0147/V air = 0-19/V Forsmall distances from the leading edge or whenever laminar flow may be anticipated, everything should 371 knots, and thus would require a hull surface finish of better than 4/1000 inch. It must also be noted that at planing speeds, the critical roughness needs to be two or three times better. Therefore the roughness of different finishes is given in Table 4, from which it is easily seen that for planing speeds, one is looking for something better than ordinary marine paint, and a high gloss, smooth finish is essential. The use of a wax polish can be helpful, but just a word of warning — it does appear that a siliconebased polish tends to trap air bubbles against its surface, introducing more drag. In so far as sails are concerned, it will be seen from Table 3 that even the thickness of battens can be very significant at quite moderate speeds. Having established the general principles of minimising drag for a given shape, it is worth reviewing the requirement for producing a shape of minimum drag since this can form a modification to existing fins, rudders and sail plans. Firstly, a look at Fig. 2, which shows the drag of various shapes relative to the shape shown at the top, which is generally round-nosed and fish-tailed. Quite clearly this is the preferred shape for minimum drag but TYPE OF SURFACE FULLY POLISHED SURFACE K in inches 0:0002 AERODYNAMIC SMOOTH PAINT 0-001 SMOOTH MARINE PAINT 0-002 GALVANISED METAL 0-006 SANDPAPERED WOOD 0-020 TABLE4 ROUGHNESS OF VARIOUS SURFACES

2 – XQ away of the wake always occurs before the section has reduced to 20% of the thickness and this also gives the advantage of reducing the convergence of the trailing edge and greater strength. It may be that this section does not provide sufficient volume to contain the weight of ballast, and so the thick- – tt 3 1-6 ZEW) SO 5 = | — a 5—Q@ —-———~+74-| 10- 3 oar cl Ae er 28-6 6 = §S ——— — — 9-3 | FIG.2. = 23-4 — RELATIVE DRAG the ratio of thickness to chord is dependant very largely on the angle of incidence of the fluid flow. For fins and hulls generally, fairly small angles are encountered whereas in the case of spade rudders, quite high angles of incidence are commonplace. Thus it may be assumed that fins should have different proportions to spade rudders although both have the same overall shape. The shapes usually associated with sail plans should also be noted, ie the use of cylindrical masts and non-streamlined fittings, all of which make a contribution to the overall drag. In this respect, it will be seen that a cylindrical section of 1/10 the frontal area of the streamlined shape has 10% more drag! Earlier reference has been made to avoiding projections which may cause a change from a laminar flow to a turbulent flow, and this applies, for example, in the case of the fin position relative to the hull. It will be appreciated now that laminar flow conditions may prevail over most of the hull length of model yachts, particularly at the lower velocities and the conventional point of attachment of the fin places it in this region, so that both hull and fin exhibit laminar flow. However, with some designs such as John Lewis’ Pulsar described in April 1976 Model Boats, the fin is attached aft of the maximum LWL beam, which may be an area of turbulent flow, and so turbulent flow conditions and increased drag is forced upon the upper section of the fin. In the case of the rudder, since its high angles of incidence may give rise to considerable drag, the further aft it is sited the better, as there will then be maximum length of laminar flow forward of it. The improved manoeuvrability resulting from an aft mounted fin may in this instance compensate for any increase in drag, but so far we have not seen a Pulsar down at Poole. Insofar as keel shapes are concerned, the resultst of assessing some 54 designs indicates an optimum thickness of 15 % of the chord length, at a point 45 % from the leading edge, and this shape is shown in Fig. 3. The nose should be parabolic, but for practical purposes may be drawn by an arc having a circular radius of 2t?/3c and then faired off to the maximum section at 45 %. The trailing edge need not be faired off to a point but should have a blunt end some 15% of the keel thickness. This is because break NOSE PARABOLA (te eee ea op bois () i 20% ! | 1 i 60% —————= j 80% CHORD c FIG. 3. OPTIMUM KEEL SHAPE, FAIR OFF TO DOTTED LINES. , FOR NOSE PARABOLA, THICKNESS t! AT DISTANCE > X\4 tls 9t(t)2 4 = FIG.4. FIN SHAPE t= 6%c Sisters 100% ness t can be increased to 20°% of the chord, which is in fact a very useful compromise shape for minimum drag and would be useful, for example, in bulb keels. In the case of fins, which operate at low angles of incidence, the thickness can be reduced to 6% of the chord, always providing this section is strong enough to carry the bulb, and it is then best to use the section shown in Fig. 4, which is derived from Fig. 3, and faired off as shown. For spade rudders operating at larger angles of incidence, a thickness of 10% of the chord seems to be a reasonable compromise, and the approximate allowable angle of incidence can be judged by joining the centre of the nose to the point of maximum thickness, as shown by line A-A in Fig. 3. The maximum operating angle can then be increased by moving the point of maximum thickness forward or by blunting the nose a little. A position of maximum thickness at 30% along the chord is suggested for spade rudders, which only differ from keels in requiring max. lift for minimum-drag at higher angles of incidence. With t=10% of chord, such a section would allow an angle of incidence of about 15° before stall effects become serious. A final note on the minimum drag shape is that by sharpening the nose, some reduction in drag may be achieved, but at the expense of reduced lift and reduced safe angle of incidence. Turning now to wave drag, the maximum velocity of a given hull length is limited to approximately 1-2 “ LWL, by the wave making barrier. The velocity of a water wave is proportional to the square root of its wavelength, whilst the largest wave made by a hull occurs when there is a crest at each end of the LWL with a trough between. When the hull speed approaches the speed of its fundamental (largest) wave, the drag increases very considerably because the boat is literally trying to climb uphill out of its own wave trough; it also tends to sit lower in the water because of reduced buoyancy. Under these conditions, the hull resistance increases so rapidly with speed that moderate adjustments to the sheets make practically no difference to speed and so, on a high speed reach or run, all skippers should be on par until planing occurs. If sufficient power can be imparted to a hull to allow it to reach a velocity of 1-7 V LWL, then the hull will begin to lift and later, to plane. This is usually impossible for heavy displacement hulls but we did see RA boats planing during the gales of last October, quite spectacular! When a hull planes, its drag tends to show a smaller rate of increase with speed, because the wave drag and form drag decrease as the hull lifts. Additionally, the skin drag is reduced because the hull is higher out of the water. There is also some additional drag produced by spraymaking, so overall, the reduction in skin drag becomes the major factor in allowing high speeds to be achieved. In concluding this article, it will be appreciated that there are many other factors affecting the performance of a yacht which is perhaps just one reason why sailing is such a fascinating subject. If any experimenting is done, the most important point to note as stated by Priest and Lewis in ““Model Racing Yachts’’, is that only one change at a time should be made and the effect of the change must be observed at various wind speeds, since most parameters of a yacht’s performance change with hull velocity. *Osborne Reynolds, 1842-1912. t*The Science of Yachts, Wind and Water” by H. F. Kay, 372

MODEL BOATS Extremely close heat at the 1977 Marblehead Championships, hosted by Gosport club, between eventual a ob K2122, Axtung and third place eolus. MYA Metropolitan and Southern Area ‘RM’ Championships, Setley Lake, 24th April 1977 The New Forest MYC were again the hosts for the MYA Metropolitan and Southern area championships for the ‘RM’ class yachts. This was held at Setley Lake in the New Forest on Sunday 24th April, 1977. sented prizes to the first five skippers. The full results were as follows: Pos 1 day for high aspect rigs, several competitors found the advantage of the lowest aspect available, in fact those with sails of a smaller area had some advantage. 10 12 The Officer of the Day was David Waugh. He called skippers together and gave them their sailing instructions, and true to tradition, the first race started at exactly 10 am. This was followed immediately by an incident at the very first buoy where a protest was lodged, and some time was taken to resolve the problem. It was at first decided to have a re-race, but in MYA rules, after a collision between two boats, one must have a penalty, and it would be unfair to others if such a re-race was held. A satisfactory decision within the rules was agreed, and the event continued. 13 16 17 8 20 21 22 24 * — The triangular course gave a beat to the first mark, a run to the second, and a broad reach to the third. The whole course could easily be sailed without the necessity to tack. The wind was true over the whole course, except in the area of the third mark. This was somewhat shielded by a clump of gorse, and gave skippers a real problem, as the wind appeared to be blowing both ways at once! Most of the penalty points were obtained here. Several brand new boats made their first appearance, but in spite of their age, many of the earlier designs gave Club Woodley Type Boat Frantica Southerner Knut Moonracer Alice Kaput Lulu II Legal Eagle Jayess Mellow Yellow J N. Curtis Woodley — Frolic E. Forbes New Forest Bewitched Margo _R. Jeffries | New Forest Own design Electra D. Robinson New Forest Own design Parbri III 4 A. Oxlade Woodley — Midnight Oil J. Soper Woodley — Windracer M.Oxlade Woodley — Rising Damp _J. Clark New Forest Squiblet AeolianII J. Cohen Woodley — Flying Sorcerer N. Oxlade Woodley — Ultrasonik R.Gerrey New Forest Bewitched Sea Witch A. Wood New Forest Bewitched Jildi fT. Brown Andover _ Sally Ann D. Brown Andover — Witchway III D. Voss Andover — Benita Retired. Reg No Pts K2401 K1948 K2343 K2283 K2418 K2478 K1576 K1985 64 64 56 50 48 46 44 44 K2467 K2240 K2507 K2470 K2275 K2476 K2475 K2307 K2314 42 42 40 38 38 K2274 K1953 K2113 K2129 K?387 K2386 24 22 20 12 12 * K2035 68 38 32 26 24 1977 Marblehead Championships Unfortunately two of the 37 entries were unable to com- pete at Gosport over Easter, and since there was no chance of rewriting the cards, the remaining 35 boats were forced to sail with three byes. Racing started on Saturday at 9.55 in NE force 2-3, the wind veering to N and later to SE, falling to force 1, then increasing to 3-4 and backing E for the last heat. Top points (remembering the byes) after the eight heats sailed were Aeolus 30, Major B 29, Sula 28, Clare 27, Greenvein 26, Halo 25, Axtung and Black Rabbit 24. a very good performance, and were still able to compete with the latest on equal terms. J. Curtis (Woodley) sailing his well known modified Aguaplane design was able to build up a commanding lead, winning four races and coming second in the other two with a score of 68 out of a maximum of 72. Tim Fuller (New Forest) and John Light southerly wind greeted Sunday, the first heat taking 75 mins, but the wind veered to WSW and blew up to a limit 2nd suit. Again eight heats were sailed, Axtung dropping only two points. Positions were: Major B 58 (1B), Halo 58 (2B), Axtung 57 (2B), Aeolus 56 (2B), Sula 52 (1B), Ding Dong 52 (1B). Cleaves (New Forest) tied for second place with scores of The entry was from 27 boats, of which two did not start and was from Woodley, Andover, Guildford, Danson, Poole and the New Forest Clubs. Bob Jeffries, the Commodore of the host club, pre- J. Curtis Mod Aquaplane 2 T. Fuller New Forest Sea Horse 3 J. Cleave New Forest Klug Ghibli 4 T. Able Andover Nylet S J. Richards Danson Squiblet 6 V.Cooney Woodley — 7 _R. Potts Danson 247 L.Thompson Poole — 8~