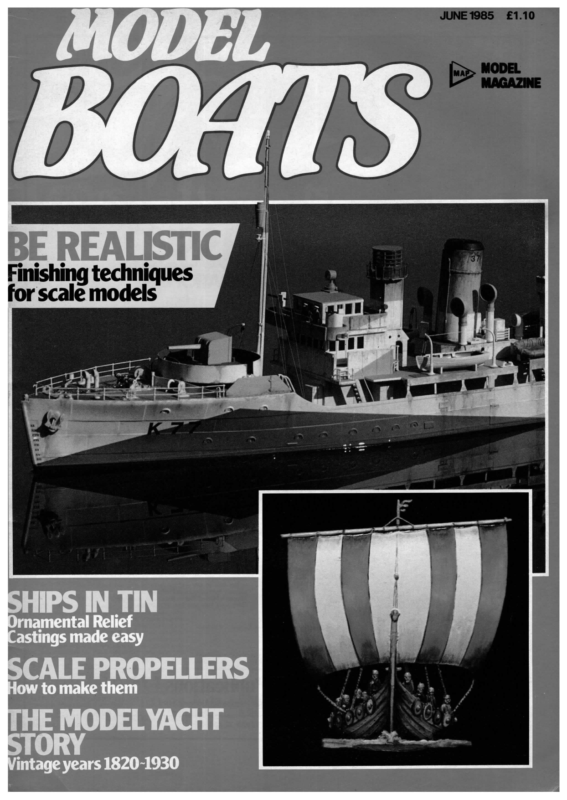

BE REALISTIC Finishing techniques for scale models SHIPS IN TIN Ornamental Relief Castings made easy SCALE PROPELLERS ow to make them HE MODEL YACHT STORY intage years 1820-1930 &

frequent shortcoming in novices’ boats is a sticky jib. It doesn’t show upina breeze, unless the geometry of the jib attachment and kicking strap is wrong, but when there is only enough air to give a yacht steerage way, or a little more, a jib which does not swing freely can delay or even prevent a change of tack. It is not uncommon to see a yacht moving fairly slowly on, say, the port tack (both booms out to starboard), perhaps heading into a region of dead air, which, when rudder is applied by a vane guy or radio starts to respond; the mainsail swings over but the jib stays obstinately out to starboard. The yacht turns almost into wind and then the jib forces its head round out of wind again. The mainboom swings about, unable to decide on which side it should be, and the yacht drifts downwind. With a radio boat it is possible to fiddle with sheets and rudder to turn the model further to starboard, to enable it to start sailing and pick up enough speed to be put about more positively, though in a race it could well be well behind by the time it is sorted out. A vane boat just has to wait until a puff or slight strengthening of the breeze gives the yacht way enough for the rudder to have enough power to overcome the jib pressure. As the bow passes through the wind the jib will normally swing over and the yacht sails away on the new tack as though nothing had happened. With either radio or vane a degree of frustration besets the skipper! “ stuck mainboom is almost unheard of, probably because the gooseneck is a better pivot than many jib attachments, the pivot line is vertical, the pivot for the kicking strap falls naturally below and in line with the boom pivot, or very nearly so, and there is a fair area of sail to exert pressure. Reduction of the tendency of a jib to stick might therefore follow if we pay attention to the pivot, consider the effect of a raked pivot line and position the kicking strap pivot correctly. There is little we can do luff tension is somehow balanced by increased leach tautness and that the load on the pivot remains constant. Whatever attachments are involved, any upward pull on the sail must affect the pivot. The rake of the jibstay means that the weight of the sail and boom is effectively hanging and to move it the wind has to blow it upwards to some extent. In the case of the mainbeam sail and boom weights are distributed along the vertical pivot-line, which might introduce a friction element but the sail merely has to be blown sideways. A light boom makes it easier to move because of lower inertia and lower vertical pivot friction, but with booms of equal relative weight, centred with the yacht upright, it is still easier for the main boom to swing. It is possible to see a difference in boom angles on a boat with heavy booms sailing in very light wind, the jib boom tending to pendulum in towards the centre. With slightly more breeze the yacht will heel sufficiently to offset this effect, but on more than one occasion we have seen a boat heel in a puff, the jib swing to the limit allowed by the sheet, the puff to pass and the jib to stay out. Free movement is more important than weight, but a light boom moving freely is the aim. although the luff of the mainsail will be drawn taut, it may not be as taut, or under | such a pull, as the jib luff, and upward pull on the sail could increase any binding friction in the jib pivot. However, while it is will thus be reduced more or less automatically if the skipper follows good practice and slacks off for light weather sailing. In many cases a conventional underboom kicking strap is not fitted on modern jibs, leach tension being achieved by tensioning the fore end of the boom via the jibstay and pivoting the boom some distance back from the fore end to give a sea-saw action. What is not perhaps apparent is that the more tension applied to the fore end the more is applied to the pivot; if you invert the set-up and regard the boom as a beam suspended by its pivot, more weight applied to the fore end increases the total weight supported by the pivot. Some people have the idea that increased 322 Some beginners fail to appreciate the importance of having the kicking strap pivoting on the same line as the boom pivot. Fig. 2 explains this. The strap attachment point on the boom will describe an arc centred on the boom pivot. If the kicking strap pivot is onlya little aft of the boom pivot and the strap adjusted to the required tension with the boom on the centre line, the slightly smaller radius the strap should describe produces increasing tension as the boom moves out, to the extent that it will stop the boom’s travel, probably before it is halfway out. It will be clear that any misalignment of the pivots, the mainsail, of course. The remaining point is tension, for reduced when everything else is slacked off. Any binding induced by normal tension influence of screw D. fore or aft or sideways, will affect free movement of the boom; the same applies to Fig. 1 about area. true that a slack jib luff will reduce a yacht’s ability to point, it is also true that in | light airs performance (full-size or model) is improved by slackening all the standing rigging, easing the flow in the sails and so on. Thus although the jib luff must not be allowed to concertina, its tension will be allows it to rotate a few degrees under the E ( : ‘ inl, 00080000) —— Traditionally the jib boom always used to pivot at its fore end and a lot of ingenuity was expanded in devising radial fittings which permitted free movement, incorporated a kicking strap anchorage, were adjustable for jibstay rake with different suits and were also movable fore and aft for trimming. One example is sketched in Fig. 1. Here the boom end is There has been a trend towards much simpler fittings in recent years, and this has extended to the jib boom attachment where there has been something of a return to the old style jib rack, which is simply an inverted T section screwed to the deck, with the vertical part drilled with a row of holes, allowing fore and aft alignment for a hook of some sort attached to the jib boom. This hook may be exactly that — a hook made off to an eye in the boom and engaging in the selected hole in the rack. (Fig. 3). The closed eye of the hook engaged in the boom eye forms a bearing comprising two cylinders at right-angles; the ‘cylinders’ are bent because both are radiused wires but they still provide an excellent bearing capable of 100-120° rotation. The hook’s open end is again a hooked or freely bolted to a pivot (A) which extends the line of the stay and provides a pivot (B) for the kicking strap. The jib tack hook engages a fixed eye (C) close to the pivot; this eye could swivel and/or incorporate a screw to raise or lower it. At the fore end a screw (D) adjusts the tilt of the body so that pivot A remains in line with the stay irrespective of the size of jib bent. This screw bears on the base of a length of channel (E) screwed to the deck and drilled along the sides for a throughbolt which holds the body in place but Model Boats

round wire bearing on the flat wall of a hole drilled through comparatively thin metal and is capable of similar movement. We need a total of 180° maximum movement, which is easily provided by this simple arrangement, with the benefit of virtually point contact at the bearings and thus very little friction even when in tension. A development is to use a fishing swivel technological age. Here we havea sophisticated sailing machine, all highly impressive but relying entirely for performance on an embarrassingly visible bit of string. Some skippers would have to remind themselves regularly that it was doing the job as well as any, and better than most, other forms of jib attachment. instead of a plain hook, but this is unlikely to have lower friction. The average swivel At the other end has a spherical body formed over two mushroom heads on the ends of wires, the wires then being formed into loops and wound off round themselves. Swivel action comes from the mushrooms rotating against the inside edges of the holes in the body, i.e. 360° contact which, under tension, must introduce some friction. The upper loop is usually engaged in an eye on the boom, by opening the eye and squeezing it closed again, but if the bottom loop is to be detachable it needs to be fitted with a hook. This makes the whole fitting rather longer than is ideal, but if the swivel’s wire is cut to form a hook itself it is unlikely to have enough strength, unless a big swivel is used and we’re then back to too long a fitting and a jib boom too high above deck (Fig. 4). oe Fig. 4 The spade rudder is now universal on at least RM, R10R and R36R yachts and most non-class radio models as well. Most RAs also use it, though exceptions can be found. There aren’t many R6m yachts yet, but the EC12m one-design calls for a traditional form of rudder on a full keel. Apart from these yachts and other occasional scaletype full-keelers, it is probably true to say that a spade is used on 99 per cent of radio yachts. Now, the average servo has more than enough power to operate a model’s rudder, especially with the balancing action of the spade, and for this reason some newcomers strong as \xin., but it probably still deflects This means that the servo has to work a bit harder, which in turn means a higher create even more friction under tension. Much of the movement would thus come from the hook and eye-bearings without the swivel doing any swivelling. Nevertheless, there are occasions when incorporating a swivel could be advantageous, and they will no doubt continue to be used. For the simplest and probably most efficient jib attachment we are indebted, itis suspected, to Squire Kay — at least, it was first seen on a Seahorse supplied ready to sail. The boom is simply tied to the rack with one strand of braided Terylene fishing line. Full stop. It is strong enough, since line can be obtained in breaking strains of up to 80]b or more, allows the boom totally free movement, costs virtually nothing, is as light as you could get and is easily renewed. Periodic renewal, before there is any sign of fraying, would be a reasonable precaution, taking up only a few moments and using up the odd four or five inch lengths of rigging line which are usually thrown away (Fig. 5). Possibly the big disadvantage is that it looks as though it’s temporary and unfinished, a real stop-gap measure in this June 1985 corrosion on the hidden part of the shaft. Oil or grease might be felt to be useful to prevent corrosion, but they have a nasty habit of turning sticky in water, especially if salt, though this may not apply to a light wipe of silicone grease. Removal may also Le] may not pay sufficient attention to the easy fit of the rudder stock, or shaft as most people seem to call it these days. Nor are the considerable forces acting in total on the rudder always fully appreciated. This was brought home on an early radio model with about a 12sq.in. rudder, pivoted a fraction too far aft and using an Y,in. brass rod stock. In no more thana fresh breeze, the first time-rudder was applied when the yacht was travelling at its fastest the linkwork over-centred, the rudder turned to 90° and the brass rod was bent to an angle of some 45°. For this reason *,,in. brass rod or in. steel have been used since. Brass ¥,; dia. is some two and a half times as by a thou. or two when a load is placed on the rudder (Fig. 6). If the shaft is a close fit in the tube, any deflection will create friction. Similarly, any slight corrosion will cause friction. It is possible to obtain shark swivels, which are very much stronger and more compact, but these appear to havea conical swivel on a conical seating, which may thin. Sloppiness is likely to mean a rudder which can move about and create drag; the fastest situation would be if the rudder was glued firmly and accurately to the hull and any unwanted rudder rattle etc. can only be downhill from this peak point. A compromise is thus needed and this could well be going to the trouble of using a bushed tube providing a close fit at top and bottom but clearance through most of its length. A good skipper will remove the rudder from time to time to inspect it for any amperage and thus more drain on the battery. A freely-moving rudder could well allow half an hour more operating time per charge, or per set of dry cells, than one which shows signs of stiffness and although this may not be important for most of the time, there are occasions when it might matter. Stiffness arising from periodic deflection of too thin a shaft will not be apparent with the yacht static, though if the tiller is disconnected and the rudder pressed sideways it should be possible to feel if friction is introduced. If the shaft is a sloppy fit in the tube, or perhaps an easy fit is a better way of putting it, there should be no problem unless the shaft is much too Deflection Bushes Fig. 6 Side load reveal any slight bend — the rudder is quite vulnerable to knocks or things catching or falling on it, and more than one skipper has been surprised to find his rudder inexplicably out of true. Once again a bushed tube offers some advantage, since that small part of the tube in contact with close-fitting bushes is unlikely to retain a corrosion deposit and the clearance inside means that corrosion would have to be extensive to effect operation. With bushes it is permissible to use grease inside the tube; water will pass through an .002in. gap and the bushes are unlikely to fit closer than this, so the grease will act as a barrier to water climbing to the top bush but will not get sufficiently watercontaminated as to turn too sticky. A short rudder tube terminating below deck is always best if bushed, to prevent water capillarying up and damping the full interior. Regular checks on the rudder, even if only by disconnecting the linkwork and satisfying oneself that the action is still smooth and easy, will pay dividends in reliable sailing. The top-performing yachts are a combination of dozens of small details like this, each of which has been checked and accepted by the owner. Even if you haven’t yet acquired the sailing skills to win, a yacht which performs smoothly without breakdown or mystery quirks of performance is much more satisfying to sail and allows you to concentrate on how you are handling it. 323

Ke the past couple of years I have been thinking about and beginning to read round the history of model yachting. My interest was originally prompted by the collection of vintage aircraft and other memorabilia on the SAM35 stand at the Model Engineer Exhibition in 1983. I knew model yachts went back a lot further than aircraft but no-one seemed to have any hard data. I have established a fairly well documented start point in the 1820’s, with sailing groups existing both in London and in Sunderland. The first records of organised clubs come in the 1840’s with clubs at Plymouth, in London on the Serpentine and a little later in Birkenhead. As I started to read the old periodicals it became clear that the building and sailing of vintage boats would have to have a place in the investigation. There are a large number of designs preserved in various places from about 1880 and a very small number from before that date. These are an important part of the evidence, but tantalisingly inadequate when it comes to understanding the problems that exercised modellers in the past. For instance, how do you manage a boat with a weighted rudder? This was the standard form of control from the 1850’s, or earlier, until the advent of Braine gear in the early years of this century. It was widely held to be ‘superior to any form of mechanical or automatic system’ but how well did it really work? Once Braine gear had arrived, the weighted rudder was derided as crude and totally unscientific. There seems to be only one way to find out. Almost as soon as I started to think on these lines I started to come across old boats. I was at first surprised how many there are and how they turn up unsought. These are some of them. Vintage Model Yach A look back by MYA General Secretary Russell Potts Shamrock At the 1984 Model Engineer Exhibition a visitor approached me for an opinion.on an old boat which he had acquired and restored. At that stage, we were able to establish from his description that she was probably a 10-rater from the turn of the century, with the twin fins that were then fashionable to provide steady pointing in shifty wind conditions. Her hatch has the carved inscription Shamrock: 10-Rater. Subsequently the photos bore this out, the relatively full hull form (Figs. 1 and 2) suggesting a rather earlier date, possibly 1899, which ties in with the date of the first Shamrock challenge for the ‘America’s’ Cup and would account for her name. The sails shown in Fig. 3 are modern replacements, based on the spar sizes, the sail area provisions of the 10-rater rule of the period and the few tattered remnants of cloth that came with the boat. There is no doubt that she was originally cutter rigged, and had not progressed to the high peaked gunter sloop rig which was just coming in for the crack boats at this time. The twin fins would havea long torpedo shaped lead slung between them. The rig is interesting in the provision of a pair of runners led very far aft. If they are part of the original they suggest that there were real problems holding the rig up when going to windward. The steering gear (Fig. 4) appears to bea reverse tiller with a quadrant pin rail to control the degree of helm applied by the pull of the sheet. This gear would almost certainly have been used only off the wind; the boat would have gone to windward with the rudder locked, as with a vane gear. This was one of many schemes of automatic Shamrock. Left: hull profile: deep chested, flat run. Fins are very small and narrow, as is the rudder. At present lacks the torpedo lead. Below left: another view of the hull: well rounded form, not the same shape as contemporary full size boats to the 10- rater rule. Below: deck view showing steering gear: relatively broad beam, main horse at counter. Sheet would hook directly to aft end of tiller for offwind legs. Above: first suit of replacement sails: main is about right, but conjectural restoration of foresails is probably not in period. Foresail should be lower and set on boom, jib should be on stay to same point as forestay and thus lower and smaller. Compare Aphrodite. Photos: John Carter. 324 Model Boats

Aphrodite III. Above: hull profile: form is that of fully developed fin and skeg for Braine gear; rudder is solid brass. Fin is considerably bulbed to accommodate lead in the right place. Note join between halves of hull. Left: running: main has a lot of twist (no kicking strap); deck fittings include a horse for each sheet; Braine gear with very large section round elastic at low tension; deadeyes and lanyards on shrouds; hatches secured with big butterfly nuts. Radial fittings for both foresails. Below: an awful lot of sail! Photos: Russell Potts. steering that were about at the time and which were shortly to be overtaken by Braine’s invention. in I have not yet had achance to see this boat the flesh or to sail her, but she is potentially in sailable condition and has had a fresh suit of sails since the photos were taken. Aphrodite III This is an ‘interesting boat, combining archaic and relatively modern features. She is a good example of the problems of using old boats as evidence. There is a considerable overlap of styles and unless we know by whom and for what purpose a boat was built, it is difficult to date a boat exactly. For instance, Bill Daniels’ famous schooner Prospero was designed in 1912, the design was available in print until after 1950 and was built to throughout this period. I have recently bought an example built in 1932, which has some features, such as braided June 1985 steel wire rigging, that don’t follow the original design. Aphrodite is now owned by Chris Jackson, the Editor of Model Yachting News, and turned up out of the blue from an unexpected source. She is a cutter rigged 10rater of about 44 inches ]wl and about 20 pounds displacement; the sail area is about 1334 square inches by the measurement rule in force before the 1914 war. The hull form (Fig. 5) has moved on a bit from Shamrock and shows signs of the influence of Daniels’ there is often a time lag in the adoption of ‘the latest style’ by home builders, just as there is a delay in the spread ofarchitectural and other fashions from the capital to the provinces. She is built in bread and butter fashion but designed with ease of transport as a major consideration. The hull is in two parts with bulkheads to give two separate watertight sections: the two halves are each held by a single bolt to the fin, which holds everything ran to. She shows every sign of being a together. There are locating studs at deck level, but no positive fixing. If the boat is lifted in the normal way by the fin, the joint in the deck gapes alarmingly. The mast also is jointed to provide the makes port. classic 10-raters XPDNC (1906) and Onward (1911), though the displacement is more than the Daniels style of boat usually home-built and designed yacht, which accurate dating more difficult as minimum problem in using public transEverything packs into a specially 325

Ripple. On the stand at the ‘ME’ exhibition: a deep full hull form, ‘like a proper yacht.” made wooden box the size of a small suit- case; even so I should not have fancied taking it all across London by tram on a Saturday lunchtime. This was a typical pattern of model yachting activity until well into the 1930’s. The sails are in such excellent condition that they may well be later than the hull. Union silk continued in use until after 1945 and overlapped the three-ply with which the deck has been remade at some stage; the two hatches are of the original 4 pine picture backing normally used for decks before the advent of waterproof plywood in the late 1930’s. The jib and foresail have radial boom fittings (Figs. 6 and 7) that give what is, to my mind, quite excessive amounts of flow to the headsails as the booms go out, but there is no suggestion of a foresail kicking strap as is found on radial jib fittings of more recent (post-1945) origin. This could be evidence of a very early radial fitting. The bowsprit is aluminium tube and almost tertainly a later replacement. The rigging, in heavy cord, is probably original and is set up with deadeyes and lanyards, as in a full-size boat, rather than with bowsies. This would suggest that the boat was not built for competitive sailing. Steering is by means of a large and carefully made Braine Gear; the fin and skeg form is typical of the fully developed Braine steered boat. Sailing the boat proved to be a problem. The years have not been kind to her and the several coats of paint no longer give adequate protection to the glue lines. As a 326 The condition of the sails is remarkable as we know they date at least from 1934, if not earlier. Photos: Mike Williams. result, there was always a doubt whether she would get the length of Clapham pond without foundering and I wasn’t able to pay much attention to how she was sailing except to be impressed by the acceleration given by the action of even a modest puff on that enormous sail area. The photos show her much more down by the head than her designer ever intended, but still show how original rig and Braine gear. She was an easy boat to sail and was every bit as close winded as the contemporary vane 36s with which she was sailing. Her speed in the light conditions left something to be desired as her power to weight ratio does not compare with that of a modern boat. She had been beautifully restored by her present owner, Mike Williams, and arranged for optional single channel radio control, so she can be sailed on waters unsuitable for free sailing. Ripple Others impressive this style of 10-rater can look. This is a 36in. Restricted class yacht (Figs. 8 and 9) which had been sent for sale to a model engineering society. She was built in the late 1920’s, almost certainly by Alexanders of Preston and was originally owned by a skipper in Great Yarmouth who subsequently moved to Luton and sailed with the Bedford club. She was registered for the first and only time in 1934 and received the number 166. She is a typical example of the best interwar professional design and construction, bread and butter built to a high standard and still as tight as when she was first made. The sails are in remarkable condition for cloth over 50 years old. There are a few rust holes and creases and the whole sails are a little tired looking, but they are still effective and set well. By November 1983 the restoration was complete and I borrowed the boat to display her at the 1984 Model Engineer Exhibition; I also took the opportunity to give her a gentle sail, using her Apart from these boats, I know of two Aboats by Bill Daniels, dating from the early 20’s and a 12-m of earlier date all being carefully looked after in the North, together with a 36 from the early 50’s. In the September issue of Model Boats there was a photo of Destiny, built in 1933 to the Gudrun Elvira design of Sam Berge and Marblehead K1 is still in sailable condition. There must be many more. If the history is to be properly written, I need to see as much of the evidence as I can; surviving boats are an important part of the evidence and I would welcome any information on others that exist. If you have one, or know of one, please let me know; if you have an old boat and don’t know much about it, I may well be able to help you establish its date and origins from the collection of design and construction data which I am building up. Contact Address: R. R. Potts, 8 Sherrard Road, London SE9 6EP. Tel: 01-850 6805. Model Boats

more than 20 boats try Clive Colsell, 22 Orchard Road, East Preston, Sussex BN16 1RB. Radio Racing Schedules are available from Russell Potts, 8 Sherard Road, Eltham, London SE9 6EP, 6-24 boats £2.00 per set, 25-30 boats £1.00 per set. Computer print-outs for 31-35 boats are available on loan for a returnable deposit of £3.50. Russell also supplies copies of the 1985 Constitution at £1.00 and, useful for clubs, the Regatta Management Guide at £1.50. A recent introduction is the availability of two VHS video tapes, “Let’s Go radio Sailing” and the 1984 RM Championship or one of “What it’s all About” and the 1982 Dunkirk World Championships on the N ew printings of MYA rules are now Any order should be accompanied by a runs of such specials are now too expensive. The new booklet, Competition Rules, Rating Regulations & Vane Racing Rules cost £1.00. The looseleaf Radio Racing Rules (with 1983 amendments) cost £1.00.A Class rules are 50p, 10 rater M, 6m & 36R 25p each. Binders are £1.00. Thusa complete set of rules in a binder costs £4.50. Yorke Gardens, Reigate,Surrey RH2 9HQ. Chris can also supply rating certificates for A, 10r, 6m, M & 36R at 12p each, £1.30 per dozen (all one class or mixed as requested) and Declaration Cards at 10p each, £1.00 per dozen, plus of course 20p post per order, and Vane Racing Schedules, 4-20 boats at £1.50 per set. For schedules for other. Copies may be had for £10 inc. P&P available, together with a bright red minimum of 20p postage and should be binder. This is astandard size, which helps _ sent, with cheques made payable to the to keep the price down; the famous ‘blue Model Yachting Association, to the book’ binder was specially made but small Publications Secretary, Chris Jackson, 33 or can be borrowed free of charge by clubs against a deposit of £10, plus p&p, from Ken Shaw, 12 Ashfield Road, Davenport, Stockport SK3 8UD. Boat and car stickers and embroidered cloth badges (IMYRU & MYA) MYA enamel lapel badges, ties, sweatshirts etc. are also available and are listed in the recently published 1985 MYA Yearbook _ and Fixture List, price 35p plus post from Ken Shaw, address above. Model Yachting Association Fixtures MAY 4/5/6 5 – 5 (L) MYA National Championship. ‘M’ Fleetwood JULY 6 Northern District Championship. R36r Etherow 7 RM Chelmsford M. Finn. & Open R36r Event. Hatfield Trophy. (L) 7 — 1985 ‘T’ Cup. RM Birkenhead Open Event. RM S. Wales Met. & Southern District RA Clapham Avocet Trophy. RM Kings Lynn Charnwood Cup. 12hr Endurance Race. R10r RA Leicester Crosby the Gosport R10r Woodspring Championship. 5 Wilkinson Sword. RM New Forest | 5 5 Canada Cup. Captain Cook Shield. RM RM Poole Cleveland 7 13/14 Shackleton Cup. 36r Leeds & 14 Met. & Southern District T2, Eric Nuttall Memorial Trophy. RM 21 South Western District 12 Met. & South: District RM Hove 12 S. Western District Championship. RM Cheltenham Gilbert Cup 6m 19 19 Northern District: Championship. Met. & Southern District 19 Midland District Championship. 19 Curry Mug 12 12 (L) Waller Cup. RM Championship. 18 (L) 18/19 Ashton 24hr Race. Championship. 25/26/27 = : Lincoln Bradford Fleetwood 14 RM Gosport RM Birmingham Ashton 21 Thornhill Trophy. RM Leicester 10Or 10r Newcastle MYSA 27 27/28 Open Event. MYA National Championship. 575 RA Chiltern Poole — 6m Bournville 28 Northern District Championship. 36r Birkenhead 28 Open Event. RA Poole RN Gosport MYA National Championship. RM Fleetwood —pionship — aeeven! and ee ee eee 4 Appledore 11 RA Birkenhead 11 R36r Championship. . 9 Sapte : 3 Midland District Championship. 9 Eastern District Team Championships. Midland District Championship & MacDonald Trophy. Northern District Championship & Northern Team Championship. 15 15/16 16/16 Solent Harwich & 18 10r Dovercourt Birmingham 18 ‘A’ Fleetwood RM R10r Woodspring Hinds Cup. RM SE Essex 16 (L) Model Boats Trophy. RM Tucker Trophy. Barnaby Dunn Trophy. Nyria Cup. Sandylands Trophy. RM RM ‘A’ 36r Red Rum Trophy Whirlwind Trophy. Open Event. RM RM RM (L) 29/30 30 30 30 MYA National Championship. (L) June 1985 » RA/R10r __10r Woodley Chippenham Leicester Doncaster Gosport i Birkenhead Gosport Cleveland Leicester Chiltern RM are – Fleetwood Fleetwood Leicester Midland District Championship. R36r Fleetwood : Clevelan “ Open Event. si oe Yorks: Cash Register Trophy. RM Leeds & Andrews Memorial Trophy. 18 Leicester MYA National Championship. Open Event. 18 RM (L) 23 23 23 23 11 R10r Crawley A MYA National Championship & Yachting Monthly Cup. _ Northern District Championship RM & Northern Team Championship. : 16 23 6hr. Endurance Race. : : 4-9 inc. RM ‘A Windsor Trophy. AUGUST Ladbrook Trophy. R36r Mayoral Trophy. 28 Haven Holiday Trophy. Birkenhead Open Event. 21 (L) Leicester RM RA/R10r Poole ‘A Met. & Southern District Birkenhead Spastics Cup. 9 9 Championship. 21 (L) (L) R10r 21 8 9 Cole Cup. Championship. Open Event. Welford Trophy. Taplin Cup Parks Committee Cup. 2 2 (L) ee : ea a mimenieg Bradford : , Ss: Western District: Championship R36r Woodspring ; Chiltern 18 24 & Mickey Finn Open. M. Finn R10r Met. & South: District Championship. : ; Eastern District Championship. — RM Open Event. RA MYA National Championship. 36r Birkenhead 25 Wyre Trophy. RA Fleetwood Rocket Trophy. Cup. RM 36r ee Ceeds Bradford Lincoln tare 24/25/26 SEPTEMBER 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 (L)_ Brayford Trophy. Belton Memorial Trophy. Laidlaw Dixon Trophy. Bilmor Cup. Wicksteed Rose Bowl. ; RM nee Saeco esc r ia RA/R10r ase ~ PEAeS M EASES 327