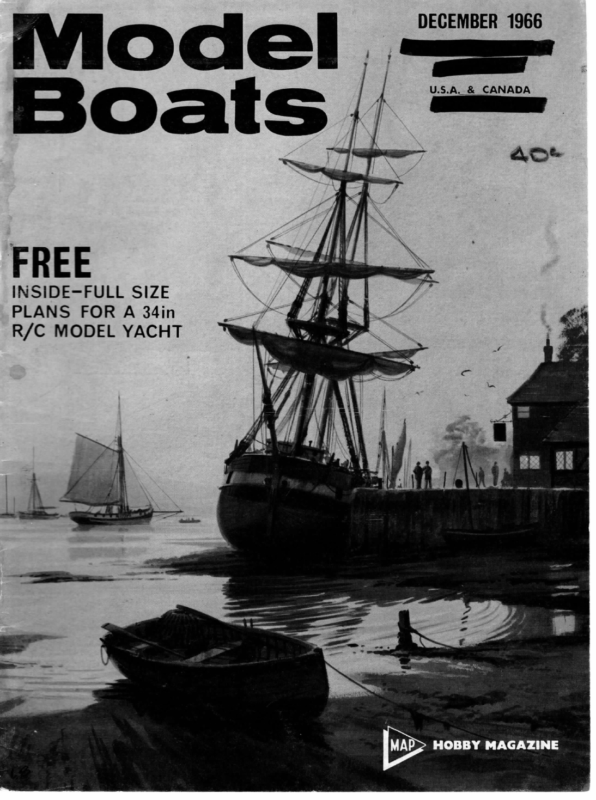

—— © U.S.A. & CANADA Ade Pal \ PLANS FOR A é j 4 % * é INSIDE-FULL SIZE C % A y F r %, sy My : Ps . i t i 34in R/C MODEL YACHT MAB> HOBBY MAGAZINE

SPAN INE YOUR CHRISTMAS FREE PLAN—A 34in. Yy YACHT FOR RADIO OR FREE SAILING. DESIGNED BY VIC SMEED FOR THE ‘BOATING FOR BEGINNERS’ SERIES. (THERE can be no doubt that radio control is one of the dominant factors in modelling nowadays, and noticeably in aircraft and power boats, In yachting, however, the same degree of R/C activity has not been achieved, though this does not seem due to lack of interest. It is reasonable to say that a majority of R/C aircraft and power boat operators have been attracted to the hobby, as newcomers, because of the scope offered by radio; many old hands are still flying or boating without radio, but the present strength of these movements is very largely a result of the influx of new modellers over the last few years, attracted by the idea of being able to control models by radio. Not, note, attracted by the radio itself—only a very few find their pleasure in the actual electronic aspect. In yachting, there has been nothing with which to get to grips. The thought of converting an ‘A’ boat to the Q class is not so very terrifying for people used to yachting, especially if they are near a water with a clubhouse offering storage, but to someone who is simply attracted by the idea of a R/C yacht, the size etc. is, to say the least, a little daunting. The R class, in catering for many existing boats, still comes out too big, and too involved inasmuch as modifications are usually necessary. Another complication has been the necessity for superhet equipment, initially rather larger and heavier and so much more expensive. With such equipment now beginning to be considered more the normal than the unusual, and with size and price gradually reducing, the time seems opportune to fill the need for an inexpensive and handy sized model yacht which could prove the answer to more R/C yachting. The M.Y.A. is prepared to consider propositions put forward by clubs for the adoption of new official classes if a sufficient number of boats of the proposed class are already sailing; a figure once mentioned was 50 boats upwards. The possibility of an ‘S’ class for tadio may well one day arise, We worked on the idea of about 450-500 sq. in. of sail on a waterline of 30 in. or less, l.o.a. between 1.1 and 1.2 x WL, and displacement 10-11 lb. A simple formula could easily be produced to cover this sort of size. Really it boiled down to the smallest conventional type of model in which the radio weight would not exceed 20 per cent of the total. Starlet is the result. It should be mentioned that the model jis equally suitable for free sailing, with, naturally, an increase in the lead weight, and details of the necessary differences in fittings etc. will be given in due course. a For simplicity, cheapness, and speed of construction hard chine boat was an obvious choice, with a symmetrical bulb keel to reduce the bother of casting lead to a minimum. We toyed with the idea of a hollow glass fibre bulb filled with lead shot, which avoids casting entirely; the main snag is the possibility of cracking it and losing half the ballast! The method of construction may not be entirely orthodox for a yacht, but it is straightforward and simple. We have incorporated a simple cabin, the purposes of which are to enhance appearance and to raise the hatch well above deck level; there is also the rather cunning support for the sheet lead eyes, which turn the sheets through less than right-angles and keep them as short as possible. The boat looks well without the cabin, so that it can be classed as an optional extra. A ‘plain aluminium tube is used as a mast, since this can be bought fairly easily, but an alternative wood one will be described, There is, we believe, nothing in the model which cannot be bought easily or made from easily available materials. Quite a number of letters are received from readers in search of yacht fittings, and certainly they are not items frequently stocked by most model shops. However, for this design no particular difficulty is offered for anyone with a file and a vice, and we understand that in the very near future fittings specifically made 498 for this model will be available from

DECEMBER 1966 Acro Nautical (Marine) Models, at 39 Parkway, Camden Town, London N.W.1., so that even those who do not fancy metal work will have no problems. Sails are another item which many people prefer not to tackle, though we shall give brief notes in due course. Here again, W. Jones, 57, Forest Road, Birkenhead, Cheshire, is prepared to supply readyfinished sails at a reasonable price. Since the sails are the power unit of the model, efficient ones are essential. Still taking the hard work out of it, we shall be ina position to supply ready cast bulbs in the near future; in lead these would be expensive—something like 30/- a pair plus postage—but we are making arrangements with a local foundry to supply them in cast iron, when they are expected to work out at rather less than half this price. The difference in size of the cast iron is about 4 in, thicker than the lead pattern shown, which, it is felt, will not prove unacceptable. Some idea of the total cost, doing it the “de luxe” way, can be roughly worked out. Ply for framework need cost no more than 6/-, for skinning and decking about 18/-. Brass tube say, 3/-, mast tube 7/6d., the paper over, lay it on the centre line on the ply, and draw over the back of the lines. Remove paper, go over the lines transferred to the wood, then turn the paper over, align carefully, and draw over the lines again. The lines will again be transferred. Repeat for each bulkhead; note that the transom will come out of the waste of one of the others. The backbone can also be traced, but it is probably then more accurate to pin the drawing to the ply andmarks pin-prick the shape through, connecting the pin Heading is a little ahead of the instructions, since here the deck has been cut and both hull and deck underside varnished. Left: stage 1, the basic framework ply pieces, with, above, these pieces assembled. Note use of rectangu- lar blocks to hold everything Below: the square and true. chines and inwales bent into place; string on B3 is a ‘Spanish windlass” to keep the chine strips drawn tightly in while the glue dries. paint and varnish 10/-, adhesive 7/6d., strip spruce 3/6d., cast bulbs approx. 17/6d. (including post), sails approx. 35/- or so, fittings (essential ones, at a with a pencil after removing the plan. The same method can be used for the bulkheads, but since only half of each is shown, lining up the centre is which adds up to £6. 10. Od., half of which at least Time to trace all these about 20 mins., and to saw them out say another hour, and the hard work is all done. The doublers can be marked (% in. ply) from the appropriate part of the backbone, Use a fretsaw for all the curved lines and the insides; the guess) 20/-, pins bolts, etc., a couple of bob—all of is the bits ready made, Even the remainder can be cut considerably, so that it is not an expensive model. One problem remains—a sail winch of the type shown, which, it is felt, will not prove unacceptable. however, a way round this, and we will mention it when we come to radio installation. Throughout, the aim has been a simple, but efficient, model capable of giving an interesting performance, without being quite so critical as some yachts. For example, design displacement is 10.7 Ibs., but three or four ounces either way should be permissible, and provided the waterline is between the limits shown there should be little difference in performance. One other point for yachtsmen—no kicking strap is shown, but this point, too, will be discussed later. more difficult. straights can mostly be done with a tenon saw. Clean up with glasspaper and check the fits of all notches. Make sure of the timber size you can buy for the chines and inwales—we used ve in. X % in. spruce, but } in. x ¢ in. will do—and check these notches, which can save work later on. Mark the fin position on the backbone, then glue the doubler area outside the marks, place a doubler in position, and leave under weights to dry. We used Construction The worst bit of building a model from a plan is tracing and sawing out the wood parts. In Starlet’s hull there are five bulkheads (including the transom), a backbone, two doublers and the fin keel. All these items were cut from three 9d. offcuts of 5 mm. (8; in.) ply, the largest of which was the piece for the backbone, plus some scraps of ¢ in. ply. We see no objection to cutting the skeg as part of the backbone; ours wasn’t, simply because the piece of ply wasn’t wide enough. Tracing paper (ordinary greaseproof) is best for the bulkheads. Mark a centre line on the paper and on the ply. Lay the paper over the plan, position the centre line, and draw over the half bulkhead. Turn 499

MODEL BOATS complete the chamfering of the backbone and bulk- heads ready to receive the bottom skins, A sharp trimming knife, chisel, and forward. epoxy resin, but Cascamite or Aerolite is perfectly suitable. When dry, saw through the backbone on the fin position lines, remove the cut piece, and glue on the second doubler. A ? in. x 4 brass screw through each end is an additional reinforcement. When dry, it pays to plane the keel edge of the backbone, particularly the doublers, to near the finished chamfer—it is much easier to do this before assembly than when the whole hull is in frame. The respective bulkheads can be slid in position to check the chamfer, and these can also be chamfered at this stage. Now drive a line of panel pins or headless nails into a flat board, in pairs spaced to that they will hold the backbone, upside down, straight and true. An alternative is to glue small wood blocks to the board or, if you happen to have them, simply use heavy rectangular weights, Glue and fit all the bulkheads in place, slip the backbone into the jig, and check that each bulkhead is square to the backbone, using pins driven into the board to hold them square while the glue dries. The glues mentioned are suitable, or Cataloy can be used, or any good waterproof glue. As a point of interest, we weighed the backbone, bulkheads and four spruce strips before assembly and the figure was a shade under fourteen ounces, When dry, and while still in the jig, fit the chine strips in place and allow to dry. It is easiest to lift the frame from the jig to fit the inwales, but by this time some stiffness is apparent and it is not difficult to bend these into place without distorting the hull. Check carefully by eye and replace in the jig to dry. The next step is to chamfer the chine strips and Above: taking a brown paper template. Crease line along keel has been marked with ball-point pen. Left, fitting of skeg and rudder trunk. epoxy Surplus must be filed away. Transom will be veneered to cover joints. a small a glasspaper plane or shaper block make this plane, a straight- It pays to make a paper template of the shape of one half of the bottom, Pin the paper to the frame and run the fingers along the edges to make a crease. Cut along the crease, replace the paper, and check that the fit is exact. Tape the paper to the ply (outside grain fore and aft) and mark round, then cut cut. Only the keel edge need be accurate; allow + in. overlap on the outer edge and ends, Tack in place on the frame and ensure that the keel edge runs truly down the centre of the backbone, then remove, carefully chamfer the keel edge, glue the contacting surfaces, and replace the panel, using the original tacks to ensure accurate positioning. Use dressmakers’ steel pins to pin the ply in contact, every couple of inches or so round the outline. Repeat for the other bottom panel, again using the template (there should be no difference, but—!) and leave to dry. Now trim the overlap away with a sharp knife, finishing flush with and at the same angle as the chines etc. Check that the side skins will lie smoothly in place, and repeat the procedure, except that a small overlap can be left all round and, of course, the hull will not be in the jig. It would be difficult to distort it seriously at this stage. When dry, trim off overlap, and, with the knife, cut away the surplus ply over the fin slot. Plane away the inwale top edge flush, and otherwise ensure that the deck will sit smoothly. The bow blocks can be simply blocks each side, glued in, then carved and sanded, or they can be laminated as were ours (as drawn). Obeche or other light timber should be used, and half an ounce or so can be saved by cutting away part of the centres. Not that it’s critical, but weight saved in the ends of a yacht is always an advantage. Carve and sand to follow the lines of the hull and blend in smoothly. Now comes the first bit of simple metalwork. The rudder trunk is a piece of thin-walled brass tube vs in. o.d. which will run from the base of the skeg through to a fraction above deck level—just under 7 in. altogether. Half of its diameter will be sunk into the rear edge of the skeg. We need small + in. doublers on the backbone, top and bottom, since we have to drill a x6 in. hole for the tube through vs in. thick ply, and reinforcement is therefore needed, If the skeg was cut in one piece with the backbone, this hole will obviously take a bit of fiddling, and it would be best to drill a zs in. hole against the skeg and enlarge it forward and sideways with a rat-tail file or, if available, an Abrafile. The half-round groove in the skeg trailing edge could be formed at the same time. If the skeg is cut and fitted separately, first drill the x% in. hole through the backbone, insert the tube, and then fit the skeg accurately; it will need a slight V in its top edge as well as the back groove. It is essential that it is truly vertical, so make sure the tube is true to start with. Drill the top of the skeg to receive two 14g or 2: in. “dowels” of brass wire about 1 in, long (thin brass screws would do, with the heads cut off) and drill, accurately, holes in the backbone to receive the top ends of these dowels. They reinforce the joint and may prevent a damaged skeg. (continued on page 522) 500

MODEL BOATS KUBERNETES design has gone abroad but should be racing at Fleetwood next year. Then we had Vital Spark which was quite different from Moonshine in that she incorporated those narrow A dissertation on the A class and a new heavyweight design by John Lewis Vital statistics are LOA 86.75 ins., LWL 60 ins., displacement 79.36 Ibs., (disp. cube 12.89), LWL beam 15.5 ins. QBL 55.3 ins., Draught 13.1 ins. (AvF—4.62), sail area 1457 sq. ins. (square root 38.18). Half size drawings as opposite are available price 12s. 6d. post free from Model. Maker Plans Service, 13-35 Bridge Street, Hemel Hempstead, Herts. [J URING the past two years I have been concen- trating on A class designs and have somewhat neglected the 10 rater class which was for so long my major interest. However, I hope that before the end of 1966 there will be a couple of new 10 raters which will show that I have not deserted that class and that rater design is still a long way from being fully developed. The main reason for the particular concern for the A class has been a considerable interest in full-size ocean racer design, and of course the A class comes nearest to anything resembling R.O.R.C. racers that we have in the model world. At long last the big chaps have decided that the fin and skeg configuration must be adopted and we are going to see quite a change in the sea-going yachts. Olin Stephens is doing it in his latest designs and this alone means that others will follow. Much money is being spent on the testing tanks and there is no reason why some of this research data should not be used in the A class in particular. However, the external manifestations of research in the R.O.R.C. classes must not be slavishly copied by model designers. The R.O.R.C. rule encourages extreme beam, slack cross sections, very fine bow sections and heavy displacement—much heavier than the heaviest International A class model. These things do not necessarily contribute to the fastest possible boat; they only provide a good handicap under the Rule. In fact, from a naval architect’s point of view in his search for speed and seaworthiness, the R.O.R.C. rule is a bit of nonsense. What is important, though, is the data being accumulated and from time to time leaked out in the yachting press. A lot of this information can be applied to model design. Very useful papers are obtainable from Southampton University, where much basic research has been done. Regular readers of Model Boats may remember my Moonshine, Moby Dick and Vital Spark designs which appeared over the last few years. What I have done during the last 12 months is to produce a complete family of designs as developments of these three basic types. Firstly we had Moonshine which proved to be a very capable yacht and quite a number of the design have been built. Then came Top Hat, a very near sister to Moonshine and if anything a little faster, but the design differences are so slight than one could not expect a radical change in performance. I have now produced a further development incorporating lessons learned during the last three or four years and which I believe will provide a distinct improvement in performance over Moonshine. This 510 rounded shallow sections typical of my 10 raters. She proved to be quite good but obviously would have been better if she had been bigger. Vital Spark, better known as Mersey Beat, is now in Copenhagen and it will be interesting to hear how she gets on over there. The development of Vital Spark is Boreas which was the iast A design of mine to appear in Model Boats. It took me a long time to develop the lines of Boreas so that the extra length could accommodate the increase displacement necessary, but we finally succeeded. The keel design of Boreas has caused some comment as it has an almost vertical leading edge. This was not done without careful thought or without previous experience, but nevertheless I understand some versions of the design are being built with considerably altered keels. In view of this I shall probably design an alternative and see if the Editor will add this alteration to the drawings in the Plans Service. All the same, from what we have seen of the early sailing of this design, it promises to be very good indeed and I have high hopes that it will be a real prizewinner. I have built a Boreas hull which Ken Jones at Birkenhead is fitting out, and between us we will see just how good she is. With luck she also will be racing at Fleetwood next year. Early last spring I designed a development of Boreas with a slightly shorter LWL and the same displacement, thus picking up a useful bonus of 50 odd square inches of sail. This design also has a more conventional keel shape. She has been superbly built by Ken Jones and she looks every inch a winner. Although she is going to an overseas owner, she too should be sailing at Fleetwood next year and there will be no doubt about her being tuned and sailed to perfection. Ken Jones is also to build the Moonshine development mentioned earlier, and again there will be no doubt about the tuning and sailing. These two yachts should provide some stiff opposition for the British contingent! As lighter relief from this serious design work I produced, in embryo form, a very narrow deep V’d section hard chine A boat and, who knows, it might even be a winner if I could find a good owner! I also toyed with the old idea of accepting a dis- placement penalty and turned out for further examination some designs I did in 1953 on this basis, one of them very long, one very short in best light displacement ocean racer fashion. As a matter of interest, I was so attracted to this idea at the time that I made a half model of one which now forms a decoration plaque in our living room. It is most appealing, but on the basis that a good big one nearly always beats a good small one, I have dropped the line of thought for the time being. Taking a displacement penalty and accepting the reduced sail area had been done quite a lot in the U.S.A. until the heavy boats proved their worth, and also Tucker tried it out over here with only moderate success. One existing A boat of my design and build also carries a slight penalty, and she seemed to suffer quite a bit due to lack of power in heavy winds and lack of sail area in light winds. However, she was not designed as such but is a modified full keel type built in the first instance

DECEMBER just to prove to myself that the fin and skeg type is best. Naturally on alteration from full keel to fin and skeg she lost displacement, hence the penalty. Despite all this though one might be attracted back to this approach again in the future as I have in mind certain developments which may make all the difference. If designs drifts steadily in one direction, say, towards heavier and heavier displacements, it only wants someone to be patient enough to see the enemy committed and then to produce a lightweight type, win a couple of races under ideal condi- tions, and be hailed as inventing a “break through”. Everyone gets unduly concerned, rushes towards light displacements and our “crafty one’’, then brings out a heavy boat. And so on and so on does the pendulum of fashion swing. It behoves, therefore, the astute designer to keep in touch with all aspects of design and not to follow one line of approach to the exclusion of all else. Now, whilst the design development of Moonshine and Boreas, etc., were going on, Ken Jones had built the first version of Moby Dick and was quietly picking up prizes during this season. To the best of my knowledge she has won four firsts, two seconds, one third and two very low places in nine starts. This is not at all a bad start in a first season for a very radical A boat. At the time of writing these notes she is in Hamburg, and I shall be most interested to hear what the Germans think of her. The design of Moby Dick is an attempt to get out of the dimensional rut into which the A class seems to have fallen. With a LWL of 60 in. and a displacement of 76 lbs. she cannot be called anything other than very large. In hull shape she is quite normal with weakish sections and no attempt to push the rule with respect to quarter beam length, The only feature which was unusual for me at the time of the design was the keel which has no deadwood. It was a problem to design a shape which would contain all the necessary lead and which would, if anything, be of less lateral area than usual for an A_ boat. It was reasoned that with such a large hull and small sail area the lateral area could and should be reduced. I think that those who have seen Moby Dick perform will agree that she is impressive. Tremendous stability, very deceptive speed due to the long LWL and easy hull form, extremely high pointing characteristics to windward, directionally stable in a reach and no mean performer down wind—ruin to another boat that gets in the way of that 76 lbs. travelling at speed, but with an elegance that her size enhances. Her windward performance is quite outstanding. Naturally there are snags, but not as many as one might have expected. For example, she is so long that when stopping to retrim you have to stop the boat and then walk back to the stern to adjust the vane. If you are unfortunate enough not to have weathered your opponent from leeward berth and have to stop and wait for the opposition to turn first, you lose about three lengths in getting up speed again and this, on a pool smaller than Fleetwood, is the end as far as that board is concerned. Her inertia in getting under way on the down wind legs is such that it is imperative that a spot on trim is held and she does the course without resource to a retrim. However, once under way, “flat spots” mean nothing because she just flywheels on and on and on! Good spinnakers are essential, or should I say, even more essential. KUBERNETES uM J. A. Lewis THE MODEL MAKER PLANS SERVICE 3-35. 1966 ORIGGE STREET, MEMEL MEW>STEAD. ERTS 511

MODEL BOATS She is very exhausting to sail and Ken Jones and his mate must by now be very fit men! Incidentally, Ken was wise in not fitting her with the usual carrying handle so that she just has to be picked up by two people. In light winds, say, under Force 2, she is slower than the more normal A boat but not much. In the two races where she was badly placed, the wind never exceeded about 7 m.p.h. and most of the time there was only the faintest ripple on the water. Nevertheless, although she was being beaten it was frequently by only a boat’s length either to windward or downwind, so the difference was quite slight. I saw both these races myself, so was able to judge whether there was any possibility of making a positive improvement in the light weather perfor- mance. I came to the conclusion that several things could be done and these are incorporated in the new design Kubernetes. One must bear in mind that Moby Dick was a trial design in many ways and did not seek to exploit the sheer size of her. She is as normal as possible as far as model design is concerned. Having seen over a complete season of racing what her range of performance is like, one can see many ways of making her even better and some of the data resulting from tank testing can be incorporated. I don’t think I shall apologise for not describing in detail each individual feature that has been incorporated in Kubernetes. Some information has come to me in a confidential way and I’m not going to break that confidence, but certain features are so obviously different from my usual designs that some explanation is necessary. For some weeks now I’ve been wondering whether to publish this design at all, or whether to just build it for myself and bring her to Fleetwood next year to complete with the rest of the family previously described. However, the time available to build is somewhat uncertain, and although still tempted to keep this design up my sleeve I decided that it is only reasonable to make the design generally available as has been my usual policy. Whilst on this subject, some people have the idea that I’m not prepared to produce a “one off” design to individual requirements. This is not the case, but, of course, the number I can do is strictly limited. What I do find encouraging is that people buy the drawings in order to study design to enable them to design their own yachts. I’m all for this as long as they don’t slavishly crib ideas without knowing the reasons why certain things are done, or merely make insignificant alterations to claim a design as their own. As far as Kubernetes is concerned, the position is that I intend to build her and, irrespective of any other A boat, I want to see how she compares with Moby Dick. If she is distinctly better then I shall believe that some of the latest tank developments can be used elsewhere in model designing; if not I shall be very surprised and so will be some professionals! It so happens that all I want to incorporate in the new design should improve light weather performance so the exercise is a “natural”. The first and most noticeable alteration is in the profile. Kubernetes has the fashionable “soft” profile on the Olin Stephen’s full-size yachts. This change has been dictated by the Tank as it has been shown that this shape, devoid of any toe in the keel, and with a long raking leading edge, has a lower resis- 512 tance and better performance to windward the ‘ype with a steep leading edge to the fin. than I believe, but have not yet proved, that this is only true on deep V sectioned heavy displacement hulls. Moby Dick has just this, so it is easy to change the profile considerably without radically altering the cross sections other than making them a little more V’d than before where the new profile demands, Boreas, on the other hand, just could not be designed with such a profile as her hull is so flat in section—hence the opposite approach to her keel design. Of course, the “soft” profile will not allow the C.G. of the lead to be as low as with a steep profile, but who cares when there is 60 lbs. to play with? In fact the top of the lead line in Kubernetes is only ix in. higher than that of Moby Dick, but the C.G. will be higher due to the changes in cross section. Perhaps, therefore, we can now see three types of A class emerging. On the one hand there will be the Boreas type with a narrow, flattish floored medium waterline length (i.e, 57/58 in.) and displacement comfortably just in excess of the rule minimum. The fin keel is almost bound to be of the steep leading edge type and the total wetted surface of the yacht will tend to be rather high. This last factor will mitigate against her iin light airs but she should on the other hand be able to travel very fast in heavy winds, particularly on the run. The second basic type may be the 60/61 in. LWL 76/82 lb. deep V’d hull with “soft” profile. This type should have less wetted surface than the Boreas type and a hull form of less resistance also, There- fore she should be all right in light airs despite the loss of sail area. She will be slow starting due to inertia, but on the other hand there will be benefits from this inertia when sailing in variable wind strengths. Her long LWL will give her an inherent high maximum speed, but she will not plane as soon as Boreas. The very thought of Moby Dick or Kubernetes on the plane and having to stop them in high winds is quite something. Even Kubernetes is not the full development of this type, but to have departed further from Moby Dick would have destroyed the value of the comparative sailing trials which must take place to establish a useful data. She could be narrower and deeper, and also have home, for example. considerably more tumble- Thirdly, there must be the inevitable comparison between the two. Like all compromises she could be very good most of the time but always vulnerable to being defeated by one of the more specialised versions, Before leaving the subject of profile and cross sectional influence, I had previously mentioned Olin Stephens and it would be quite unfair of me not to point out that several British designers have also adopted this general style for very many years. I have in mind David Boyd and Robert Clark in particular. They persevered with this characteristic even when Laurent Giles’ ocean racers such as Myth of Malham were doing so well with their steep leading edge fins with a most pronounced toe. One must also appreciate that the Stephen and Clark boats tended to be heavier displacement types than those of Laurent Giles. In fact if you look at any of the cross sections of Giles’ yachts you would think that you were looking at Boreas. It should now be abundantly obvious that it is

DECEMBER i366 I believe not enough attention is paid to this and is one of the reasons for the turbulent boil visible in most fin and skeg designs when sailing to wind- no good getting excited about a particular type of profile without also examining the cross section and displacement/length ratio. With bigger, heavier A ward. boats and limited sail areas, the question of wetted surface is going to be more important than ever before. I suggest that not enough attention has been paid to this by model designers up to now and only some vague comments are made about such a design having ‘“moderate”’ or “average” wetted surface, the judgement as to greater or lesser area being made on a quick glance at the profile. How deceptive that can be. A light displacement hull with severely abbreviated fin keel, perhaps with a bulb at the bottom, has a much greater wetted surface than one would think. This is, of course, why a number of fast-looking 10 raters and Marbleheads lie around like logs in the water in light airs. I’m not getting at anyone in these remarks, as I’ll admit to being as much at fault as Next we come to the skeg and rudder combination. Kubernetes has an arrangement which is quite different from anything I’ve done before and_ is frankly a copy of the latest Olin Stephens ocean racer designs. I have always thought that the skeg should be as small as possible, but have up to now provided an adcquate length on the bottom edge to fit a conventional lower pintle arrangement, This new tiny skeg will have to be made from something tougher and more rigid than wood—say Tufrol. The lower pintle is integral and the pivot will have to be upside down when compared to the usual type. In order to remove the rudder without having a removable skeg it may be necessary to cut a slot in the hull above the rudder to allow the rudder to lift off. The rudder tube will also have to be of large enough diameter and allow the rudder post to be withdrawn canted to clear the lower pintle on the skeg. I’m sure it can be done, but an alternative more normal skeg and rudder is shown as an optional anyone. However, what I have done is to calculate the actual wetted surface of some of my designs and the results are surprising. In future I shall do this calculation for every design so that I can build up a set of comparative figures. In the case of Moby Dick the actual wetted surface is 1177.6 square inches and this has been reduced to 1134.6 square inches in Kubernetes. Now a casual look at the profile changes might even cause you to think that Kubernetes has the greater wetted feature. Because Kubernetes is a heavy boat it is possible to make full use of long overhangs. The length of the forward overhang will come into good use when in heavy weather. It is also good for crossing the line a few inches ahead of an opponent, remembering that model races start with the sterns level and surface, The other point regarding wetted surface is that although it is the major source of resistance for most of the speed range in which we sail, the value of this resistance is not uniform all over the hull. There are areas of high pressure with possible laminar flow and areas of low pressure with undoubted turbulent flow. It is reasonable, therefore, to cut away the turbulent flow areas rather than the laminar flow areas. Incidentally, this also reinforces the argument for long leading edges to the profile rather than the severely cut-away bow the longest boat is going to get its bows over the line before a short one! All other things being equal, which they rarely are. wards the rear edge of the fin, there is not much point in fairing the thing off to the much advocated knife edge, is there? It has been shown that cutting five per cent of the chord off the trailing edge of a streamline section does not affect the resistance, but it does reduce the wetted surface. Now in the design of Kubernetes I have not attempted to design an all-lead fin as in Boreas or Moby Dick, and this has left some deadwood, I have in mind trying a trim tab which can be set at, say, three deg. on either tack to improve the windward characteristics, This has been done on some windward, With a heavy boat like this it is important of a moving carriage type vane gear and it is cer- overlapping jibs for long legs to windward or reaching. This will encourage the use of bigger measured fore triangles. At the moment, when an overlapping jib is in use and the boat unfortunately comes into the lee bank jit is usually the end of that board. Sooner or later someone will invent a clever way of self- I suppose in some ways I have contradicted this argument by not drawing the after overhang out to its fullest possible length. You will see that Kubernetes has a slightly shorter stern than Moby Dick and this is for two main reasons. One is that a long stern overhang does little to enhance speed and for a given width at the LWL ending does not effectively increase the sailing length when heeled. Also the shorter stern will make her easier to swing over onto the new tack when doing pole turns to profile. Likewise, if the water flow is turbulent, say, to- to develop an effective technique with the pole in order to keep full way on but at the same time not to excite the judges too much. A subsidiary reason for the shorter stern is to provide dissimilar ends to the yacht so that pitching in heavy weather will be damped. Not much is known about this as yet. The sail plan has received some attention in that the jib is larger than Moby Dick in an attempt to improve light weather windward performance and also provide a range of larger spinnakers, Kubernetes by virtue of being slightly heavier than Moby Dick picks up a few square inches in sail area and all this plus some more has gone into the fore triangle. well-known full size yachts, notably those designed by Van de Stadt, and is a feature which theoretically should make quite a difference. I don’t see why this should not be operated by the self-tacking action We tainly something which should be tried out. Kubernetes has rather fuller garboards_ than Moby Dick and this was done mainly to reduce the efficiency of the fin for windward performance. Moby Dick has already shown that the big hull does not require as much lateral area in the fin as normal, so a further reduction in this aspect does seem to be permissible. Furthermore I have been careful to provide as clear a run as possible where the rear edge of the fin fairs into the canoe body as are now seeing more use being made of tacking a Genoa, but in the meantime what about fitting a spring loaded forestay furling gear? The Genoa is fitted with a snap shackle on the clew 513 (Continued on page 525)

MODELL BOATS TEST BENCH What’s new in the boat world INNEW—the E.D. Viking, a 5 cc. marine engine ~ ° complete with throttle and silencer, A new motor is nowadays quite an event in the boat world; this one is developed from one of Basil Miles’ designs and should rapidly make a name for itself, A full test will be appearing in the near future. New—a glass fibre hull to fit our Sun XXI tug drawings published in August’s issue. This is moulded by Magnal Laminations, 235 Lee High Road, London S.E.12, Length is 35 in., beam 83 in., and weight of moulding 2 1b. 6 oz. Colour is dark grey, and the hull is complete to deck level and has a generous horizontal flange turned in. A very nice job. Price is £4. 8s. Od. plus carriage. New—a glass fibre cruiser hull by Cortina Plastics 193 London Rd., Romford. At first glance this 6 ft. 5 in., 8 in. beam hull is puzzling, since it has a constant depth of 73 in. through most of its length. The idea is, however, that the top edge can be cut down to the hull profile of a number of prototypes (160 is claimed) to produce a reasonably scale hull. Cross-section is a little square, with flat sides and bottom, but there is no doubt that the correct sheer line would make a lot of difference. Price is £7. 9. Od. plus £2 1s, Od. tax plus 17/6 packing and delivery. New—plastic kit of the wartime Vosper 71 ft. M.T.B. by Revell, At 1/72 scale (just under a foot) STARLET (continued from page 500) Before assembly, that part of the brass tube which protrudes down from the hull and locates against the skeg must be cut away so that only half the circle remains, that is, a saw-cut must be made for a distance of 33 in. near the maximum diameter of the tube, and half of the tube removed. The remaining half is filed to be not more than a semi-circle in cross-section. Avoid bending the this. Roughen the outside and skeg, etc. with epoxy resin, tube while assemble the doing tube, SCOUT CLASS CRUISER (continued from page 502) represent, with careful use of dowelling of various sizes and brass wire etc., as also the 18 in. torpedo tubes, The guns may be left uncovered, or covered by a light shield as shown on two guns in the drawings. A 3 in. HA gun has been shown on the drawings, as this type of gun is believed to have been fitted late in the class life. All casing could be of +; in. ply, and boats, funnels, etc. of adhesive tape over formers, or carved out of solid block. Electric propulsion is probably best in a model of this type, and a speed of around 3 m.p.h., or a little more, would be quite effective for the larger size intended. Colouring—light grey topsides, black or red below this is an attractive addition to available plastics and at 10/8d. should find a ready market. New—a 44 in. modern German M.T.B., Dachs, by Graupner, with a fabulous degree of prefabrication. The entire hull bottom is spindled out of one block of balsa, and the flared section of the bows from another. The kit is a beauty to put together; mainly balsa construction means that it is better for electric power, though a strategically placed bit of ply here and there would make i.c. power quite feasible, A first class kit at £8. 7. 6d., fittings pack 38/-. New—from Billing Boats, the 32 in. trawler Progress. For those who like planked hulls, etc., this is excellent. All ply and hardwood construction, clear drawings and instructions, a fine kit for £4, 17. Od. Fittings set, very complete, is £8, 2. Od., 29/- of which is the trawl winch, and as a further optional extra, all-metal finished masts are available for £2. 16.6d. The hard work for most people is the hull itself, and most enjoy making their own fittings; the idea of offering boat and fittings separately is a good one. New—and back to E.D. again—are nylon starting cords for marine engines, complete with neat wood toggle and heat sealed cord ends. Also from. this firm are plastic-cased fuel filters to plug into the engine feed-line, and they have re-introduced toughened rubber finger-stalls for prop-flickers. Doublers are also needed on the backbone at the points which will receive screws for the mast step and jib rack, and small squares of } in. timber should be glued inside the side skins where the shroud plate bolts will pass through. The inside of the hull now requires two thorough coats of varnish, taking particular care in corners, but not varnishing the tops of the bulkheads and inwales, since glue will later be applied to these parts. (to be continued) water, decks can be shown as wood sheathed, painted dark grey, or for the model a light biscuit shade; the first funnel can have a white band about 4 way down from top, entry hatches can be fitted with canvas screens, as are bridge and structure at break of quarter deck. rails to super- Finally, although the drawings are not as fully detailed as I would have liked, I feel that a model maker of reasonable experience will be able to build an attractive and unusual model from the plans as shown. Visits to a museum or library will probably help in suggesting small departures in details to be made in the individual models—just as the full size ships were all different in some details or other, so can the course. 522 models be, within the general design, of

DECEMBER 1966 HISTORIC LINERS NO. 45 GINCE this series started, each December’s issue has dealt with one of the world’s largest liners. The pattern is repeated this year although the Amerika was Abbe is, so to speak, a smaller largest liner. By 1900, the German lines had decided that their future lay in the operation of large, comfortable ships rather than record breakers, which seemed to hold records individually for such short periods and which were so expensive to run. The White Star Line had also had similar ideas, and although the BY R. CARPENTER Cunard Line built the Mauretania and Lusitania, the real race during the first 14 years of the 20th century was between the giants. to the U.S. in 1918 as war repatriations she became the America and re-entered the Atlantic service of The Amerika was the largest ship in the world when she was built,, but she was soon overtaken by ships like the Olympia and Vaterland, The Amerika was also the last large liner to be built in the U.K. the U.S. Mail Line. She was laid up in the early °30’s and in 1941 she again became a troopship—one of the very few large ships to have seen service in Until 1914, the Amerika ran between Germany and the U.S.A. She was interned in 1914 and became a U.S, troopship in the later years of the war. Awarded service over a period of about 52 years. for German owners. KUBERNETES (continued from page 513) which can be clipped onto the ordinary jib boom in a matter of 14 seconds. The rest of the board is then sailed in the ordinary self tacking fashion. With a big heavy yacht it is not so important to economise on weight of fittings and there is prob- ably some advantage to be had in designing full tracks for both jib and main sheets. Similarly, as it is a good thing to have everything as aerodynamically clean as possible, what about an under deck radial jib boom fitting? The mast should be as clean as can be and there is really no need for external fittings at the hounds. One still sees useless masthead forestays doing nothing except preventing the mast from bending backwards just when such a bend could be made useful with a full cut mainsail. It seems to me that a lot of development work remains to be done on fittings and the cut of the sails. We do not control the flow of the sail suf- ficiently. Certainly we are more ready to have flow on the sail and to use the outhauls to control it. SMALL CRAFT (continued from page 521) (Towage) Ltd., of Rotherhithe Street, London, the John White was formerly the Silvermark within the fleet of Silvertown Services Ltd., part of the Tate and Lyle sugar combine. Now owned and operated by the White Company, both wars. The end came in 1957 when she was scrapped in America—a very fine ship which gave excellent This does not control the actual position of the flow in a fore and aft direction. Should we return to lacing the foot of the sail to the boom and control the sail by bending the boom with the mainsheet? The sail would be cut very baggy and a much lighter material used in the region of the boom so that the bag will move over in light airs. Why shouldn’t we use a Cunningham hole in the mainsail to control luff tension? Incidentally, Kubernetes with her wide deck will have an advantage over yachts with heavy tumblehome when it comes to using a Genoa! There are lots of things not properly tried out as yet and it seems to me that a big powerful model is just the thing on which to experiment. All the things mentioned above will be tried on my own model if I am given the time to do so. There are a couple of others as well, but I’m sure no-one will grudge me keeping just a little something up my sleeve. her superstructure limits. This is not too usual among craft units but is a welcomed feature for tow rope handling purposes during operations. Colours: Hull black, red boot-topping, white trim lines, white name. Decks dull red. Inside of bulwarks, brown. Superstructure brown. Mast brown. Fittings, black. Funnel, black with white letter “W” both the diesel tug is a useful vessel about London’s tideway scene. She is powered by British Polar diesel engines of 500 b.h.p., ample for her type of operation. A slightly unusual point about the vessel is the big clear space available for crew working aft beyond sides. Liferaft container, white. M. C. COBRA (continued from page 505) LUGGER (continued from page 507) will you be travelling a greater distance, but the turn will not be so smooth and so well controlled as it would be if BC were followed. To sum up then, know your boat’s turning-circle and practise running at a distance of half this circle parallel to a line of buoys and turning earlier so as to nudge the end buoy of the line. The turn should be made in one sweep. If you can master this tech- nique then you will turn in times which are comparable to a boat some 2 or 3 miles an hour faster than Note: For scale purposes the John White is 78 ft. in length overall. by the ‘ketch’ which was a more efficient sailing vessel besides being rather easier to handle. A further reason for the waning popularity of the lugger at this time was that vessels, especially fishing boats, were tending to be built bigger and above a certain size the lugger was a most difficult craft to manage. As late as 1859 a large lugger, the New Moon, 134 ft. long, was built, and, although very fast under ideal conditions, was not an easy vessel to race when ‘ia boards because of the time taken to dip her ugs. yours. 525