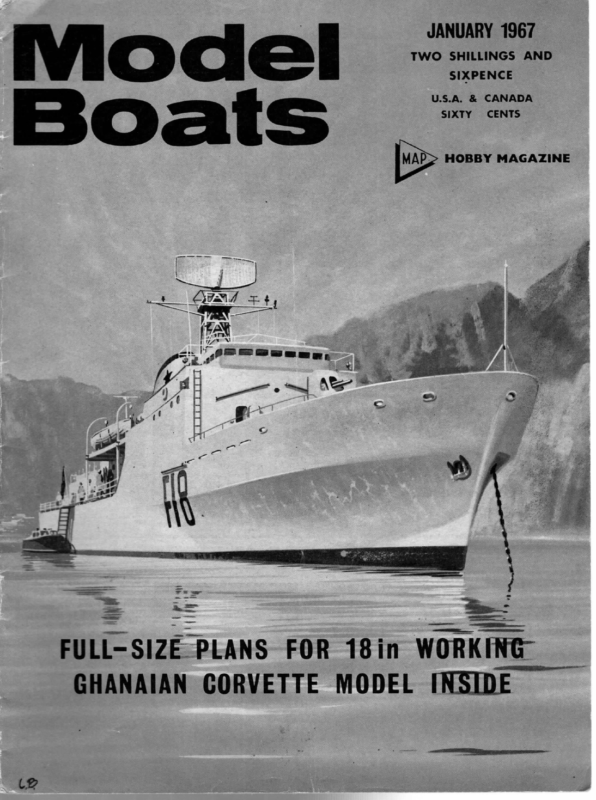

JANUARY 1967 TWO SHILLINGS AND SIXPENCE U.S.A. & CANADA SIXTY CENTS | as Ce a 7 i HOBBY MAGAZINE cence TET FULL-SIZE PLANS FOR 18in WORKING eae nae S SP recess COI

||a a aaa ~~ MODEL BOATS BOATING FOR BEGINNERS OF THE CONSTRUCTIONAL — PART TWO NOTES ON = tin BUILDING OUR CHRISTMAS FREE PLAN STARLET ‘Two jobs go hand in hand with stages discussed last month, the rudder and the deck. We left the skeg drying out with a cut brass tube fitted to its after edge and running through to project slightly above deck level. This is referred to as the rudder tube or, more correctly, as the rudder trunk. The rudder stock is the bit that fits inside the trunk, to which the rudder is actually attached. In Starlet this is another length of tube (though it could be brass rod with a small hole drilled in its lower end) which is an easy fit in the trunk—with 7% in. o.d. for the trunk, + o.d. could well be the size for the stock. It doesn’t matter if it is a slack fit; better that than tight. This stock has to fit in a groove on the fore edge of the rudder blade, in such a way that a movement of about 20 deg. either side of the centre is obtainable and the rudder moves easily. At one time screws used to be driven through the tube into the rudder and the heads filed to the diameter, but nowadays epoxy resin provides an entirely sound joint, if the brass tube is roughened slightly with glasspaper before sticking. For the loss of a little streamlining a brass sheet rudder could be silver soldered to the stock if preferred. The stock eventually will be pushed into the trunk (from beneath, of course) and held in place by a pintle plate. This is a is in. wide strip of brass screwed to the bottom of the skeg, projecting beneath the rudder and carrying a pintle pin which engages in the lower end of the stock. This is the reason for a hole being required if a solid stock is used, An alternative is to drill a hole in the plate extension, through which the tip of a solid stock could pass, but this is a less efficient method. The pin can be a rivet or cut-off brass nail soldered through the plate. y N E LL | MU Y // 34” YACHT FOR FREE-RUNNING OR R/C The deck is a single piece of ys in. ply and the best way to mark it out is to drill a hole in the sheet to slip over the short piece of the rudder trunk which projects above the backbone. Locate the sheet, bend it to touch the inwale all round—it can be done single-handed quite easily, but an assistant makes an error less likely—and draw round the hull with a pencil, Cut out outside this line—a good ¢ in. spare should be allowed—and try for fit. Mark a centre line on the top face, and from this mark out the cut out hatch area, Cut the hatch, using a trimming knife and straight edge, using several light cuts rather than one heavy one which could score the ply if it slipped. A saw can of course be used if preferred. Varnish the underside of the deck two coats, keeping clear of the edges which will be glued; a chance is usually taken on areas which will be glued to bulkhead tops or deck beams, as it would be difficult to varnish adequately while leaving strips unvarnished here and there. Provided the deck edge is firmly secured no harm will come, especially as some of the fittings screw through the deck into the frame and will thus hold it. Our preference is to glue the deck firmly on, but some builders bed the deck on wet varnish and use fine screws or pins to hold it down. This certainly simplifies removal of the deck if at some time in the future it is decided to strip a boat down for a complete refit; we feel, however, that with such an extensive refit a new deck might be best anyway. If using glue, then, glue and pin the deck in the same way as the bottom and side skins, removing the pins when the glue is dry. If varnishing, use brass pins tapped home. Leave to dry, then trim the edge flush, using a sharp knife and glasspaper. We decided to get a couple of undercoats on the hull, so that they could be drying while we cut out the cabin pieces. The next job therefore was to cut and fit the fin keel, which is simply glued in using At the top the stock needs a short threaded stub, which can be run on a solid stock with a die, or, for the tubular stock recommended, a short length of appropriate brass bolt soldered in. For a radio model, the rudder should swing with reasonable freedom, though the servo power will normally be enough to overcome minor friction. For a free-sailing model, however, the rudder must be absolutely free; unfortunately oil cannot be used to lubricate it as it simply goes sticky in water. epoxy resin or Cataloy. The latter makes it easier to run a very tiny fillet round the junction of the fin and bottom skins, using a toothpick or scrap of balsa to smooth the adhesive and form a “corner”. Surplus can be sanded away when dry, if not too great an amount. Incidentally, we use bun baking 12

JANUARY 1967 cases for mixing Cataloy, since only small amounts are mixed at a time and the used paper case can be discarded. A careful check must be made to see that no misalignment has crept in during construction; the method is pretty fool-proof but it is as well to check that the fin is truly vertical and in line with the bull centre line. When dry, sand over the entire hull in readiness for painting. If you want a veneered transom, now is the time to do it, as the veneer will need two coats of varnish to prevent any paint that may creep on to it from marking it permanently. The cabin structure shown on the drawing is optional and some builders may prefer to save a couple of ounces by omitting it. On the other hand, it does add to the appearance of the model and it reduces the amount of water likely to get inside the boat by seepage through the hatch and mast mounting. We would recommend it for radio; for free-sailing it depends on whether you like the idea of a semiscale layout or would prefer functional simplicity. To make it, draw-out on the deck the area covered by it in pencil, and glue on + in. sq. obeche or spruce down each side. Cut the bottom line of one cabin side to fit the deck; the plan should be used only as a guide, since individual decks are bound to vary slightly. Having fitted the bottom edge, mark or trace out the side on to the ply and cut out. If you mark it all out before fitting the bottom edge, it may end up like the chair that needed one leg shortened! Use the first side to fit the second—there may be very small differences at deck level. Pin these sides temporarily in place, then cut and fit the ‘S’ pieces. These should be individually fitted to the deck camber, so again, their tops should not be cut until the fit of the bottom edges is assured. When all pieces fit, assemble with glue, pinning till dry. Note that S5 does not need an ¢ in. sq. fillet strip, though one can be fitted if desired. Before adding any more to the cabin, it is desirable to fit the mast step, and while making this the jib rack may as well be made. Two short pieces of brass curtain rail are required; brass is emphasised because some curtain rail is a soft alloy with a brassed finish. The actual pattern is not important since we only require the T edge on which the runners roll, the opposite edge, which may vary, being cut off and discarded. The dimensions and finished result are clear from the drawings, and the only tools needed are a small hacksaw, a thin file, and a drill, plus, preferably, a vice to hold the work. We find it best to cut the T section away for a few inches as a first step. Two lengths are then cut off this for the step and rack, and the stem of the T cut away at each end so that holes for fixing” screws can be drilled. The embryo fittings can be filed to finished shape, radiusing corners etc., before slitting the step or drilling the rack. Before slitting, check the thickness of the piece of brass to be used for a mast tongue, since the slits should be wide enough to accommodate this freely, but not wide enough to let it slip fore and aft. A scrap of 18 s.w.g. would be best; a little thinner would be acceptable. Cut the slots carefully with a junior hacksaw, making sure they are vertical, and open them to the right width with a thin file, such as a magneto points file. To drill the jib rack, simply mark the hole centres and punch them lightly; a wire nail can be used, but change it after every punch mark. Better, in the absence of a proper punch, is a hardened masonry pin. Only a light tap is needed. Use a Yes in. drill for the rack holes, and up to 4 in. for the end fixing holes which should then be countersunk. Other fittings for fill-in jobs are the mast bands etc. The photograph shows how these may be formed. Cut a strip of 22-24 s.w.g. brass ¢ in. wide and bend % in. of the end at a right angle. Use a ? in. or slightly smaller dowel and a wood block in the vice to bend the strip mto a smooth circle, and when three-quarters of the way round check the length required to complete, cut off, bend the end ? in. back, replace in the vice and complete the bending. Drill the end tags accurately, slip a bolt through and tighten, then file both end tags to a neat radius. Note that the bands should fit tightly on the mast and that the gooseneck one must allow for a Ubracket and the hounds for the jib hoist plate. You may prefer to cut a card template from the truelength pattern given and try this for size, making adjustments to the template before cutting the brass. The mast itself is a piece of ordinary ? in. o.d. aluminium tube, which is stocked by many D.LY. shops, caravan accessory stockists, etc., but if any trouble is experienced in locating it—or ex-W.D. tank aerials or similar—a wood mast could quite easily be used, and we will give the necessary details in a future instalment. For the metal mast, first cut the tube to length. Cut a wood plug 1 ins. long to fit tightly in the bottom, and tap it in. Don’t use unnecessary force, but at the same time a good tight fit is needed. Now saw a slot across the centre of the tube bottom, + in. deep; make sure it is across the maximum diameter. The mast tongue, mentioned earlier, is a 3 in, square of brass fitted into this slot and glued with epoxy resin. As additional security drill through the front of the tube and the tongue, countersink the hole in the tube, and screw and glue in a 5/16 in. brass screw. File when dry to leave the mast a smooth diameter that will pass through a # in. hole. In the centre of the bottom of the tongue file a small nick so that it cannot slip sideways off the mast step. HAH

MODEL BOATS FLAMINGO OVER the last two years or so, several new boats have emerged, which indicates a breakaway from the popular medium length, heavyweight, 10R concept. At least three of these, including one designed by the writer, have a waterline of 60 ins. Ten raters of this length are nothing new, but in the past, tended to suffer perhaps from being a A bulb-keel, waterline long 10-rater in all respects. As in the previous ‘M’ craft, draught is limited to a reasonable figure so that she is not restricted to a few sailing waters. There is nothing particularly unorthodox about the concept either in hull or fin. Although the displacement is quite moderate, her righting power is greater than any fin keel craft to the rule. For this reason it was decided to give her a very high sail plan and spinnaker hoist, Only the flattish, beamy sections can effectively damp out any tendency to roll when carrying such a sail downwind. It seemed inadvisable to combine a 12 in. beam from the board of 5. VV Se FLAMINGO DESIGNED 5 S witty COPYRIGHT THE MODEL MAKER PLANS SERVICE fS 35, BROGE STREET, HEMEL HEMPSTEAD, 5 LENGTH OA LENGTH WL 74.4″ 57:5″ 12″ DRAUGHT 3s DISPLACEMENT 28-5 LBS SAIL 1036-2550″ MAX HERTS. 6) BEAM AREA ALLOWED little too far ahead of the state of the art, the most common grumble being that they lacked power, due usually to a reduction in beam and weight. With both beam and bulb, however this will certainly not apply to the new design, and performance should be enhanced 10435 sq” 26

JANUARY with a 60 in. W.L. owing to the increase in wetted area. As drawn, the proportion of wetted to sail area is approximately the same as in a 55 in, W.L. hull of similar beam. The sections are shallow, but not too hard, so as to heel fairly easily over the initial few degrees. This seems to improve the light weather performance and helps to keep a nice curve in the sail. The canoe body is, however, quite normal, combining good all round capabilities, yet able to plane quickly and easily when there is any weight in the wind. Bulb keels and appendages can now be “balanced” so well that mast positions are little different from those in ultra conventional craft. A helpful factor is that balance, or lack of it, is largely a product of heel. The powerful righting effect of the bulb-keel therefore tends to improve the balance. That this effect is not cancelled out by the tall rig is indicated by the fact that on most boats the optimum mast position with such a rig tends to be rather aft of that for a low top suit. It may be that with the extra stability provided by the bulb-keel, the masthead rig may become popular. Indeed it has become almost universal ‘in certain types of full-size craft and the high foresail is certainly more effective to windward. 1967 Some years ago, in the days of Union Silk, we tried out a double-luff mainsail, Though at the time the results were not very encouraging, it seems that this idea may be revived with success, now that a more suitable material, such as the new dinghy cloth, is available. If so, it will affect the balance of the mast position, for as the mainsail becomes more efficient, so the mast position must be moved forward. The optimum depth of the keel for this concept is 13.5 ins., factors to consider being depth of sailing water, stability, balance, length and wetted area. The rudder post is swept 18 deg. and although some prefer an upright post, I feel that the reduction in drag is enough to make the former well worth while. Angular movement over the limited range required is not great; not enough to need universal joints or anything complicated providing the angle of sweep is not more than about 20 deg. With fairly shallow sections and moderate displacements she will be responsive to the guy and easy to turn from the bank. On the whole I feel sure that the design will prove to be an extremely fast and able ten-rater. BOOKS Two new offerings from Her Majesty’s Stationery Office have recently been received. The smaller of these is a Science Museum “Four-in-One” Book and is in fact four previously published card covered 5s. books on various small craft and ship models re-made into one hard bound volume, Titled Ship Models, the 6 in. sq. volume contains nearly 200 pages, 80 of which are full colour illustrations of models, from a coracle to a ship of the line, covering craft from all over the world and over a wide range of history. Enthusiasts for period ships and/or small craft will want it as a permanent reference; price is 18/-. The larger new publication is a magnificent work entitled H.M.S. Victory, Building, Restoration & Repair, written by A. R. Bugler, O.B.E., previously Constructor, H.M. Dockyard, Portsmouth, and_ is introduced as an official Admiralty record of repairs to the Victory. Actually, the work goes much further than this—it describes the original building of the ship, timber pests, shipwrights’ tools, dry docking, bomb damage, and a host of other related facts which make fascinating reading. At first glance, the book appears to be in two volumes, but closer inspection reveals that the second “book” is a cunningly disguised box of drawings. With these drawings, plus others and sketches and complete dimensional tables of just about everything, contained in the book, it would appear that enough information is given to build a complete and accurate full-size replica of the vessel! The book itself is 11 in, x 8} in., with some 400 pages plus 57 plates, (mostly whole page photographs) and 43 pages of detail drawings. The whole work is most lavishly produced and is well worth the £8 price. There could certainly be no excuse for an error in a model of Victory after this! Either of these titles may be purchased direct from any of H.M.S.O. retail shops, or through any bookseller, 27

MODEL BOATS 285 | 406 285 FIG.1 eh er +4 5 678910 0 406 i | Wares ervey ferrites Pen $0 60 80, 1p0, THIS IS A TYPICAL SCALE DRAWN ABOUT ONE THIRD FULL SIZE.A 12 INCH SLIDE RULE IS MORE FINELY F knere E.G. THERE ARE FIFTY DIVISIONS BETWEEN ONE of the most frustrating SCALING Plan the UP OR wrong size? things about ship spent on actual construction. It is, of course, possible means that totype is The method used by the writer requires only the redrawing of the deck outline in plan view, all other dimensions being read directly from the plan and being converted to model dimensions by the use of 683 we can convert 500 a slide rule. The only exceptions to this would be 1200 the redrawing of any shape not rectangular in contour such as some of the cone shaped funnels found on many modern merchant vessels. Even the hull profile can be calculated without redrawing if you 64 100 to an accuracy of ft. long and is to be modelled at by the calculation:— xX 683 = 285 units. x 285 = 445 units long. The modeller may, however, find a slight error in many plans due to stretching or shrinkage and should are crammed on including functions of angles, squares and cubes and so on. You can, in fact, buy slide rules specifically for certain types of computation, and what might be a suitable slide rule for not be alarmed if the plan is a few units out, He should always use the measured length in such cases, rather than the calculated one. Many plans, particularly those in naval annuals, do not indicate a scale. Here it is simply a matter of for an electrical engineer is quite inappropriate for, say, a physicist. All the modeller requires, however, is the standard logarithmic slide rule which measuring the plan with the 1:500 scale and noting the number of units. The larger the measurement taken the more accurate will be the result and the can be purchased for a few shillings. A twelve inch slide rule would be the most practical to buy for model work. The six inch pocket overall length should be used whenever possible. Let us say that our drawing has an overall hull length of 406 units. We will then have a model that variety can be used in the same manner but are not always as easy to read. The scale you will use is the one immediately above the slide. It will be noted that the figure “1” appears at the left and “100” at the right. The numbers in between are spaced logarithmically, that is they are positioned on the rule in locations corresponding to their common logarithm. The reason why “1” appears on is 285/406 times the plan size. It is again a matter of simple arithmetic to convert back to feet to the inch scale, which, in this case would be:— 100 the left is that the logarithm of “1” is “0”. A typical scale is illustrated in figure 1. x 285 = 70 ft. to the inch. This, however, is merely of academic interest since we have already established the relation between plan and model, and this is all that is required for construction purposes. It is good practice to record this ratio, 285/406, in some convenient location where it will not be mislaid, such as the corner of the plan. All the The scale immediately below that is identical, the only difference being that it is on the slide and can be moved in relation to the upper, fixed scale. In all model work, particularly in the miniature field, it is essential to forget the common units of feet and inches with their awkward fractions, and convert to a decimal system. Millimeters can be used for larger models (there are 25.4 to the inch), but a finer division is required for the miniaturist. In this respect a surveyor’s 1:500 scale is probably the most practical. On this scale 500 units represent one calculations written out above can be done very quickly on the slide rule; however, it is left to the reader to master multiplication and divison from the instructions which usually come with the slide rule. All the modeller requires for the time being is a knowledge of proportions, It might be useful at this stage to give a few hints on reading the slide rule. Since the spacings te t measure been drawn to a scale of 1/64th inch to the foot. The length of the ship on this plan will be 100/64 times the length of the model, and the plan, if drawn correctly, should be:— muliplication, division and proportion can be mastered after only a few minutes practice. Most slide rules look formidable because several scales 3 can Let us now suppose that the plan we are using has are using bread and butter construction. To the uninitiated, who might regard the slide rule as some mysterious and highly technical device, it should be pointed out that it is an extremely simple instrument, and that the basic calculations of j you 1:1200 or 100 ft. to 1 in scale, we know it will be 6.83 inches long. Since 500 units represent 1200 feet plans. 2 rules? 1/2000 of a foot, which should be accurate enough for models down to and including 1:1200 scale. To establish model length to this new scale is a matter of simple arithmetic; for example if a pro- to have the plan reduced or enlarged photographically, but this can be expensive and it not always areas particularly if you are dealing with large FIG.2 slide foot, which is just under 42 units to the inch, It is sufficiently well spaced to make it easy to read, and the divisions are far enough apart to permit the judging of a half, or even a quarter, unit by eye. This tedious chore, taking up time that could be better L of It really is quite simple if you follow these notes. modelling is the variety of scales at which suitable plans are produced. It invariably seems that, when one finds a plan of the ship one wants to model, the scale is different, usually by some odd fraction, This makes redrawing an essential but 1 Scared DOWN 4 | 34

JANUARY 1967 are logarithmic the divisions are not always of equal value but depend on their positi on on the scale. On the left of the rule, between “1” and “2”, there are fifty divisions each division corre sponding to ‘.02” FIXED SCALE ‘\% whereas in the centre, between “10” and “20”, we find the same number of divisions each corresponding to “2”. The other important thing to note is that the slide rule does not place the decima l point for you and 4 i836. 7 it i CURSOR HAIR LINE you can use the same Positi on, say “2.8”, for “280”, “2800”, or even “0028”. The decimal point FIG.3 3 COM Pi T TTTTin must be positioned mentally. This being the case it number on the other. In our example “14” and “20” towards the centre of the scale, and there are two positions of the rule correspondin g to any number divided does not matter whether you use “2.8” or “28”, selected, It is simply a matter of convenience which one you use, the result of the calculation will be the same. Since “2.8” can be used to represent “280” let us now find “285” on the upper scale. There are twenty divisions between “2” and “3” therefore “2.8” must be sixteen divisions to the right of “2”, and “2.85” must be one further divisi on to the right of this. The position is illustrated in Fig 2. If the number had been “2.83” or “2.86” the position would have to be judged by eye since no divisio n accurately ‘ locates these figures. Since the decimal point can be anywhere we can use this position for “285”. Set the cursor (the glass or plastic slide with a hair line) over this position with the hair exactly over “285”, We must now locate the secon d value on the sliding scale. “406” will correspond to “4.06” and is found just to the right of the first division to the right of “4”. The division itself represents “4,05” and we must calculate the additi onal “.01” by eye, this being one fifth of the distan ce between the “4.05” position and the next divisi on corresponding to “4.10”, Move the slide so that “4.06” is exactly on the cursor hair line and, therefore, direct ly beneath “2.85”. The rule will now appear as in Fig. 3 and is set up for operation. Do not, on any account, move the slide again, just the cursor, It is good practice always to check the rule after it has been put away or if has been dropped or knocked, It is not a bad idea to fix the slide in this position with clear Sellotape if it has easily. a tendency to move too It is now a matter of measuring a dimension on the plan, locating this on the lower scale, and reading the equivalent mode] dimension on the upper scale directly above it. This of cours e works very well when dealing with rectangula r shapes, but what about curved plan lines and other irregular fea- tures? There is, unfortunately, no alternative but to redraw these to the model scale but, here again, the slide rule provides a few conve nient short cuts. The basic requirement for any plan is the outline of the deck. This must be redra wn to model scale. To do this a centreline must first be drawn the correspond. The centreline of the plan must now be into you THT FIG.4 “20” éach will have one and, shorter division on at the one The distance between the hull sides can now be measured on the plan and transferred to the model layout, marking each point earefully and making sure that the two points repres enting the deck edge are the same distance from the centreline, All measurements must be made from the centreline out. As you work towards the centre of the ship you will find that the hull sides appro ach parallel, and for that section where they are parallel no further computations are necessary. On very small scales you will be working down to one half or even one quarter of a division on a 1:500 scale. When all the points have transferred to the mode] layout the points may be joined. A draughtsman’ s french curve will be of help but is not essenti al if you have a good eye. Where greater accuracy is required, or where the curvature is very great, it may be necessary to use smaller divisions between the paralle l lines, In our example we could use “7” and “10”. This is somesometimes useful at the bow and stern using the larger divisions elsewhere. This same method can be used to-make templates for checking lines on larger models, the essential requirement always being a base line from which all dimensions are taken. The base line can actually be anywhere on the drawing as long as the dimensions can be made at right angles to it. To establish rake or any feature at an angle to the centreline other than a right angle all one has to remember is that the angle will always be the same no matter what scales are used. Once the inter- section of two lines are established one has merely to draw a line at the correct angle through the point. (Continued on page 39) FIG.5 USE SET SQUARE SET AGAINST RULER FOR PARALLEL LINES | PARALLEL LINES 14 UNITS APART of end. This end must correspond on both plan and model, that is if it is at the stern on one it must also be at the stern of other. Now draw a series of lines through these division points and at right angles to the centrelines, using a set square (Figs. 4 and 5). length of the ship (the plan may be covered with tracing paper for this stage if you do not wish to mark the plan). On a separ ate piece of paper draw another centreline, this time to the length of the model. Referring to the slide rule note where a whole number on the one scale coincides with a whole me divisions the model centreline, into divisi ons of “14” each, In each case BO AFTER ALL POINTS ARE DRAWN JOIN THEM TO FORM HULL OUTLINE. 35 HHH