NOVEMBER 1971 5p USA & CANADA SEVENTY-FIVE CENTS HOBBY MAGAZINE

‘a MODEL BOATS The Birkenhead One-Design Catamaran Ken Roberts outlines the story behind Bill Perry’s design and gives some hints on building and sailing DURING 1970 racing of model yachts at Birken- the spaced drawing. The vital statistics are: 48 in. head was severely curtailed due to lack of water and large patches of weed. The only people who were enjoying their sailing were a few of the junior members who were sailing catamarans. It was agreed by the committee of the Birkenhead Club that Bill Perry, who has had considerable experience in designing and sailing model catamarans, should design a catamaran that could be sailed in competition by inexperienced juniors and the more experienced seniors. LOA. 22 in. Beam. Weight 7 lbs. Sail area 283 sq. inches. The prototype model sailed so well that nine pairs of hulls were produced in glass-fibre for members of the Birkenhead Club. The hulls can be conveniently turned out in glassfibre once the mould has been prepared. The hulls can also be made by conventional timber methods. Once the two hulls have been constructed there is not a lot of work to be done. Inwales + in. x +} in. have to be fitted. Where the booms connecting the two hulls fit, the space has to be filled in with } in timber, flush with the inwale top. On top of these wood inserts are glued the wedges to which the booms are attached. The shells can now be decked, filling in the space either side of the wedges with The design conditions agreed to were: 1. The overall length of the hulls to be 48 in. long. A hull length of over 48 in. would produce a catamaran which would sail too fast for some less active skippers to keep up with. 2. The catamaran should be simple in construction and fitting out. 3. The catamaran should be cheap to produce. 4. There should be no complicated steering gear. The boat which Bill Perry designed is shown in ys in. marine or exterior plywood, Armourboard, or Melaboard. The deck can be either screwed of glued on. It is most important that both hulls weigh the Full-size copies of the plan below (i.e. full-size hull, half-size plan, and quarter-size sailplane) are available, ref. MM1121, price 65p post free from Model Maker Plans Service, 13-35 Bridge Street, Hemel Hempstead, Herts. BIRKENHEAD OD. CAT W. < PERRY torent of o The Model Maker Plans Service Herts btae 12-35 Breage Street Heme! Hemostenc “a te — be T 2 28300 co 09/0 secTIns 3.4.5.6,7. 3,10 8, vas : VE: ices ~\ Z SS oS Sr — eS — a ae \ ae =a — ; — : = o SEP SSW Re — = = “ J. UN 2 Eo eee,| Si —— Te, a ee

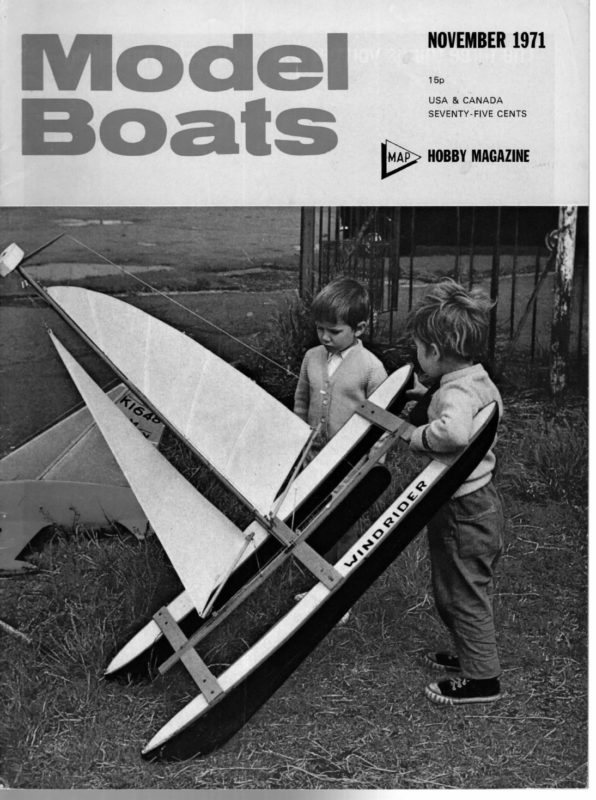

NOVEMBER 1971 Don’t be deceived by Martin Roberts’ six years of age — he knows exactly what sailing a catamaran is all about and gets some pretty fair trims. Older skippers get exhausted just watching him sail. same. If one hull is lighter than the other add lead weight at the centre of balance before attaching one of the centre deck pieces. The three booms connecting the two hulls are made from wood 22 in. x 2 in. x ? in. The booms are tapered at the ends, starting 4 in. from either end and tapering outwards to +4 in. The booms are screwed to the wedges. It is essential that the hulls are square and parallel to each other and that the toe-out of each hull is the same. A king plank 1} in. x } in. is glued down the centre of the three booms. This king plank projects 3 in. in front of the forward boom and is cut flush with the back end of the rear boom. The front centre plate is sandwiched between two brackets made from 1+} in. x 14 in. angle aluminium screwed to the underside centre boom. The centreplate is pivoted around a 6BA bolt drilled through the two brackets and the centre plate. The rear centreplate is fitted in the same way on the rear boom. It is most important that both these centre plates are in line and square to each other. ing as high into the wind as possible without going into irons. When a heavier gust of wind hits the boat it will head up into the wind and will ride out the TECHNIQUE OF SAILING A CATAMARAN Beating to windward The jib and mainsail are set parallel to each other or the jib slightly further out than the main, between 10 and 20 degrees. The forward centre plate is lowered so that it is a few degrees off the perpendicular. The rear plate is in the raised position. If the boat sails into irons (into the wind) the mast should be moved forward, and conversely if the boat is sailing too much off the wind the mast should be moved aft. In strong winds there is always a danger that the catamaran will capsize. The method of avoiding this is to trim the catamaran so that it is point- gust, then revert to its normal course when the wind lightens. Running before the wind The sails are set in the normal way for running, i.e. jib and mainsail well out, and a spinnaker is set. The forward centre plate is raised and the rear centre plate is lowered. If the catamaran falls off to the leeward bank the mainsail can be tightened in or the rear centre plate raised a few degrees. The opposite is performed if the boat hits the windward bank. ELECTRIC SCENE (continued from page 457) If the separate class idea was adopted, I think that the ‘silver class’ would soon fall out of favour and could later be dropped. It is interesting to note that as far as I can recall, Ostend is the first time that silver-zincs have won the European Championships. Prior to this year, Bordier has won several times with nickel-cadmium, and before him Willi Senff reigned supreme with lead acids. I hope that sanity can make a come-back! Other models One other model which was interesting from the performance point of view was run by a French competitor. Milani, and recorded a time of 29.4 seconds. Whilst this might not sound too impressive on first reading, three factors should be considered. The first was that, with due respect to the pilot, steering was very wide —to the extent of a couple of seconds extra time at a guess. Secondly, the model, which measured 32 in. x 11 in., was from a glassfibre 10 c.c. speed hull and weighed over 13 Ibs., with a hull weight over 5 lbs. Comparing this with the 14 1b.-2 Ib. of the British hulls, there is quite a severe weight penalty. The third reason for interest was the use of 34 Saft 1.2 a/h Nicads. During a considerable discussion on the subject of his boat, Milani assured me that he was able to get 40 amps from these cells, although I doubted whether they would supply this at a great voltage or for very many seconds. However, independent information on the new upgraded Saft 1.2 a/h Nicads indi- cates that such high currents might indeed be possible. The new continuous maximum current for the cell (formerly 1.0 a/h) is 12 amps instead of 5 amps, suggesting a great improvement. Thus the cells are obvious candidates for testing which I hope to carry out this winter when the bank balance recovers from Ostend! At first sight, twenty cells giving perhaps 18-20 volts at 20-25 amps to a Sea Ram should be capable of Naviga speed times under 25 seconds since the weight would be only 10 ounces more than DGW silver zincs. The Saft leaflet which informed me of what little I have so far discovered, also mentioned rapid charging in only a few minutes which clearly has great possibilities. The one problem of using Nicads is that the voltage drops steadily, so the first run is normally the best. The rapid charging feature could be the answer for multiple heats of multi-boat or events where runs are taken in the morning and afternoon. 453 a ees bn nee

RACING MODEL YACHT CONSTRUCTION PART SEVENTEEN BY C. R. GRIFFIN eight days by which time the sails should lie naturally against the jib stay and mast. Ideally, when the sails are not in use they should be hung by the headboard, but if this arrangement is not practicable it is best to roll the sails over a cardboard tube of about 3 in. diameter. The second matter that can be ‘dry-land’ tested is the operation of the rudder by the vane gear. This point should have been tested when the vane gear was fitted but it is advisable to recheck before trials are started. Use a template to ensure that the rudder moves an equal amount either side of the centreline when the vane moves through a specific number of degrees either side of centre. Also check that the operation of both the vane gear and the rudder is not impeded by any ‘tight’ spots. Finding the best mast position to give optimum performance. On arrival at the pond side set the mast at the designer’s estimated mast position and rig the sails so that they lie naturally, allowing the booms to rise FIG. 105 about fin. for every 12in. of sail foot. It is usual to carry out the first series of trials using the low aspect ratio or working sails. However, it does depend on the strength of the wind at the time CHECKING MAST ik the preceding article it was stated that it was advisable to ascertain the true mast position(s) before permanently fixing the keel. This statement is based on the fact that the mast was placed at the designer’s estimated mast position. However, no designer can guarantee that the designed mast position is that which will give the optimum performance of the yacht. Secondly, and what is probably more important, there is no certainty that the yacht is exactly as designed. These are the reasons why model racing yachts have devices which allow the mast position to be altered e.g. a mast step and a mast slide. Also it could well be, and often is, the case that to obtain maximum performance when using any of the designed sailplans, the mast needs to be moved in a fore-and-aft direction. To find the best mast position it is necessary to carry out a series of trials. Prior to the first launching of the yacht and subsequent trials there are two tasks that, in the writer’s opinion, can be effectively accomplished in the workshop, thus saving valuable sailing time. Firstly because most new sails stretch, time can be saved by allowing for part of the process to occur under controllable conditions i.e. away from the effect of water and varying ‘strong winds. Rig the mast either with the hull in an upright position or lying on its side and attach to the jib stay or mast jackline (or alternatives). Place the luff tack hooks into their respective eyes then adjust the jib and mainsail hoists so that a slight strain is placed upon the luff of the sails. Position the clew hooks so that the sails lie as flat as possible without strain and adjust the kicking straps, if fitted, so that no creases or rucks appear in the sails to sit in this position for, say, about two hours, then de-rig and repeat the procedure the following day, if necessary applying a little extra tension. Carry out this routine over a period of, say, about 458 and whether or not the owner has a high aspect ratio suit of sails. In any case it is likely that, over the racing season, the working suit will be in use on more occasions than will the high aspect suit. What is more important is the fact that separate trials must be performed using each sailplan to determine the best mast position for that sailplan. It could so happen that the mast positions for each suit of sails are so close to one another that a compromise mid-position involving no movement of the mast could be adopted. For pleasure sailing or for the occasional club event it may well be that this compromise mast position is adequate. However, if competitive racing is the class of sailing envisaged, then probably individual mast positions for each suit of sails will be a necessity. Lock the vane gear and rudder in the central position by tightening the centring spring and securing the tiller arm to the rudder arm so that no movement of the rudder is possible. Adjust the main boom so that the boom lies at an angle of between 10deg. and 15deg. to the centreline of the hull, the narrower angle is usual for the slim vee-sectioned hull and the wider angle for the flat bottomed beamy hull. Then adjust the jib boom sheet so that the jib boom lies at a similar angle to the main boom and ensure that the curve of the leach of the jib is parallel to the curve of the leach of the mainsail. This may mean setting the jib boom a little freer than the main boom. Put the yacht in the water with the bows pointing at about 30deg. to the wind and give it a little way. The yacht will now either continue sailing but fall off the wind i.e. gradually make a course of an open beat or a close reach. Or it will gradually point up the wind until the sails no longer fill and then flap idly in the wind, the yacht probably starting to move bodily backwards. If the former condition results, move the mast backward the amount depending on how far off the wind the yacht sailed. If the latter

NOVEMBER condition occurs move the mast forwards. Repeat the procedure until the yacht sails to windward but so close that the sails are on the point of spilling wind. In all the foregoing tests the yacht has been sailed on one tack only. Now put the yacht into the wind but on the other tack, if all is well the performance should be identical to that previously obtained. Mark on the deck the positions of the mast heel or mast slide and the jib fitting for that particular suit of sails. Any small differences in performance when the yacht is sailed on opposite tacks can be corrected by adjustment of the vane angle settings during the actual tuning up operations. However, should there be a marked difference in the course sailed on opposite tacks then it is likely that either the mast is not central and upright or the fin and skeg are out of alignment. It is advisable to check these points before proceeding further with the trials. Fig. 105 shows one method of checking whether or not the mast is upright and centrally placed on the hull. Use a straight batten of reasonably substantial cross-section, say, about lin. by 14in., mark off the centre of the batten and two points three feet either side of centre. Screw two eyelets into the top and bottom of the batten at the three foot marks, fashion two pointers from thin plywood or hardboard and thread an adjustable line through each pointer, securing each end of the line to one of the lower eyelets. Place the batten on the deck at 90dg. to the centreline of the hull so that the centremark on the batten coincides with the centreline of the hull i.e. the centre of the mast. Clamp two six inch blocks to the batten ensuring that the blocks are hard up against the hull and that the edges of the blocks are equidistant from the centre mark on the batten, distance ‘b’ in the diagram. Place the adjustable line around the keel as shown and hold in position with electricians’ tape or Sellotape. Position the pointers so that the points are on the designed waterline and check that the distances ‘a’ are equal. If the distances are not equal place packing under the batten on the shorter side. Tie a line to each of the upper eyelets in the batten so that the centre of the line lies exactly Sft. from the batten on each side. Mark the mast at a point 4ft. from the top of the batten and this point should coincide with the centre of the line. Whilst the use of the specified lengths is not mandatory it is essential that distances be of sufficient length as to minimise errors. The method of checking the alignment of the fin and skeg depicted in fig. 106 is self explanatory. The only vital prerequisite is that the line carrying the two plumb bobs be run along the centreline of the hull. 1971 beneficial to carry out a further ‘flotation test to check the trim of the yacht. It should be noted that the trim must be checked for both aspect ratio sailplans and to an extent the final trim will be a compromise unless rather complicated weight adjustments are made. It is not proposed to detail these adjustments, to those builders who possess the requisite skill and perseverance it will suffice to say that it can and has been done. The foregoing terminates the notes on the construction of model racing yachts; the further aspect of bringing the yacht to racing pitch by tuning trials is a subject that the writer feels is best left to those whose record of achievement qualifies them to speak on the matter. However, to give the beginner some idea of the scope of the tuning process, it may be said to be concerned with: 1. The balance of the complete steering mechanism whilst the yacht is in the water so that account is taken of the buoyancy of the rudder itself and that the heeling of the yacht to the normal sailing angles has no off-centring effect on the steering. 2. The ascertainment of sheet settings and vane angles to produce the highest pointing course whilst at the same time achieving the greatest speed through the water. There are different schools of thought on this subject alone. 3. The set of the sails so that the maximum effort is derived from them under all sailing conditions. 4. The verification of perfect freedom of movement of any fittings such as main horse, jib fittings etc. Primarily for the benefit of newcomers to the sport, there only remains a brief discussion on modifications that can be undertaken and an outline of general observations on any boat building project. A subsidiary to model yacht construction is the reconstruction of an existing yacht. When finance and time available are amongst the governing factors to be considered in any proposed project, rather than to elect to take no action at all, it is often advantageous to purchase, for a more modest outlay, a yacht built to an older design and then to up-date the model in some respect or other. Despite what has been said or written on the subject of early obsolescence of racing models, where some ‘pundits’ have demanded restriction on the employment of new ideas, a basically good design of hull will always remain a good design. True it may not be fashionable, but fashion is sometimes fickle. If it is accepted that that particular yacht may not appear regularly amongst the prizewinners although it may be consistently among the Assuming that the performance of the yacht is identical on each tack or is as near identical as would make little difference and that the positions of the mast and jib fittings for that particular suit of sails have been marked, de-rig and hoist the other aspect sails. Again place the mast at the designed position as the starting point and once again set the yacht off on one tack at approximately 30deg. to the wind. Endeavour to sail the same course as in the previous trials but in any case aim to sail to windward so close that the sails are on the point of spilling wind. If needs be move the mast to attain that course of sailing and when found, repeat the procedure for the opposite tack. Mark the positions of the mast heel or slide and the jib fitting if different from those found for the other sailplan. If the positions of the mast and the jib fitting are found to be different from the designed position it is FIG 106 ALIGNING FIN &SKEG PLUMB BOB mh

a MODEL BOATS rpthe construction of historical model ships is an absorbing pastime, and if these models can also be made functional they are doubly attractive. As all serious model builders know, however, you cannot have both authenticity and functional behaviour. Some compromise must be made. In the matter of sail and rigging the complexities 4 J Af . TOGGLE YARD PARREL ——— (ane { “ =e ql /s o ‘ = ua aN e = m~ N\ \ c 1 tm -majority of whom will be only too pleased to help. . Pre-plan the whole project before commencing work. . Adhere to the original planned method of building. . Attempt to reproduce the design as faithfully as possible’ Be fair to the designer, after all he did most of the original work. 6. Be critical of your own work. 7. Be patient and, willing to learn by experience. What might almost be called sail drill for period ship modellers! By A. J. R. Belford SHORTENING SAIL : construction. Study the rules of that class of yacht and seek advice from other skippers, and measurers, the ie sponsive boat. Alternatively it is possible to convert a Braine gear controlled yacht to vane gear operation or to fit a modern sailplan to an older type of hull. A word of caution must be given on ‘modifications’ and that is that it is wise,to consult others, with greater knowledge and experience, on the possible effects of the proposed alterations. Better still, if you can, consult the designer. . few ‘golden namely: capabilities methods of & Instances can be given where the up-dating has been done with excellent results, for example, the fitting of a fin and bulb keel arrangement to a conventional keel design yacht has produced a faster, more re- In any boat building project there are a rules’ that are well worthwhile reiterating, 1. Select a design that is within one’s but do not be afraid to tackle new ta leaders in certain conditions then, logically, if one enjoys the sport for the sport itself, it is better to have that yacht than no yacht at all. (An article could be devoted to discussing this attitude of mind!). = THE YARD OF A SQUARE RIGGED SHIP of cordage of the true model can be so great that sail adjustment on a working model would be impossibly tedious. Accordingly, simplified rigging is essential. This should nevertheless be at least basically correct. Square riggers, for example, with the braces carried from yard to yard and linked to the spanker sheet so that swinging the spanker boom reverses the tack of all the square sails simultaneously have in my opinion lost too much realism. One of the main problems with historical models is their instability which allows them to carry full sail only in the gentlest of breezes. It is therefore necessary to be able to shorten sail in order to allow the model to perform well in a moderate wind-— which to the model is a stiff gale. The authentic methods of shortening sail often resulted in an aerodynamical inefficiency which would have horrified the skippers of the old clipper ships. let alone the modern yachtsman. It is, however, only in recent times that the speed of a sailing vessel has become an important criterion. Sailing warships, for example, rarely sailed at their maximum rate. Their business was to keep in formations and to manoeuvre to advantage. Accordingly, the majority of early paintings show such vessels with some sails furled, others clewed up, and some yards SHEET partially lowered to reduce the sail area. Models likewise arranged are extremely realistic and depict their prototypes as they really were. Sail was of course reduced in strong winds, and this is an essential to the model sailing vessel to which a light breeze is in effect a scale gale. Variations to the square sail are as follows: (a) Backing the yards to reduce speed or to heave to. (b) Lowering the yard to reduce sail area. (c) Clewing up one or both sides. (d) Furling the sail and lashing to the yard. (e) Unbending the sail (i.e. unlacing from the yard). (f) Fetching down the yard. This list is arranged in order of severity of wind conditions. Backing the main yards was a common method of reducing speed. much quicker than shortening sail, and possessing the advantage that the ship was ready to ‘square away’ at a moment’s notice. In model work, a square rigger with the mainyards backed is SHEET = SQUARE SAIL somewhat ineffective as the excessive leeway in models causes it to simply drift broadside across the pond. The effect, however, photographs well. The complexity of ropes required for a model square rigged vessel is so great that an authentic 460

1971 IOR CHAMPIONSHIPS Birkenhead, Aug. 28-30th By Joyce Roberts Chris Dicks and his lightweight Imshallah — so light, we are told, that it flexes when you stop it! Small sail area and long waterline are obvious in lower view. P[SHERE was a larger entry than last year, 22 boats, but this is not as many as at the Marblehead Championships. Perhaps holding the race so soon after Fleetwood makes it difficult for many people to travel, but it is obvious that 10 raters are more popular South of the Mersey, one look at the results will show that there is only one boat in the North that can compete with the new long lightweights. It was certainly an eye-opener for Birkenhead, Fleetwood and Bradford and North Liverpool competitors to see the new 10’s, and to see how they sail. Perhaps this will revive a new interest in 10s locally, some new ones are obviously going to be built. Racing commenced at 2.30 on Saturday afternoon, with a strong 2nd suit wind, a beautiful beat and run. Mr. Rusty and Imshallah were the first pair to be started, and they were obviously well matched; unfortunately Imshallah was turned off into Mr. Rusty, so a race to the end was not seen. The strong wind continued for 3 heats, doing a bit of damage including bent rudders and a broken mast for Brian Garbett with his new Dicks design E. L. Wisty. He managed to do some temporary repairs and fortunately for him the wind dropped so that there was not too much strain put upon the repairs. All boats were in top suits by the Sth and 6th heats, there being very little wind by 6 p.m. Most skippers, mates and officials were feeling very chilled by then; during the strong winds mates were jumping in the lake to save the lightweight boats from being smashed up on the concrete edge, and rain had fallen for half the afternoon. Top boats at this stage were +/0 Colin Jones, 28, Mr. Rusty Roger Stollery 28, Im- shallah C. Dicks 27, Moppet, M. Harris 22. Sunday morning started with fluky reaching winds, the lake) and the sun was shining. It was decided to sail two beats, then a run off if necessary. Chris was windward first time, and he won. The 2nd time the two boats touched each other, so more retrimming was done, and Roger had the better trim, only having to guy near the line, Chris sailed across the lake. Imshallah then had her sails changed, and the final run down was watched with interest. Mr. Rusty could not hope to catch Jmshallah as a perfect run was achieved by Chris, although near the end a sudden gust made the result closer than expected. Everyone was delighted that these two boats and gradually getting stronger and after lunch they had come round to a beat and run like Saturday. In the light winds the skippers found it difficult to trim for the different areas of the lake, gusts coming between the houses. Jmshallah lost 3 to Sail On from Bradford, and Mr. Rusty lost 5 to the Birkenhead boat Boomerang. E. L. Wisty had a new mast on, and found conditions ideal. Lunch brought rain and the strong winds again, so 2nd suits were again produced. Fred Shepherd made a brief appearance, and helped Alec Austin to get Zebedee going, and Mr. Rusty, skippers had finished with the same points, and pleased that the result of the sail-off was a fair one, far better than the time at Fleetwood when Chris Imshallah, E. L. Wisty, Moppet, and Odanata revelled in the conditions. +/0 did not have such a good time. The wind lightened again after a tea break, and Mr. Rusty lost 3 to Dick Seager and Odanata, and at the end of the day Jmshallah had 66, +10 64, Mr. Rusty 63, Odanata 58, E. L. Wisty 57, Moppet 52. Monday morning was a near beat and run, but the wind tended to gust between the houses again. +/0 lost 3 to Dave Knowles and his Dicks designed boat. 2 to E. L. Wisty, 2 to Moppet, and 3 to Odanata. Imshalla lost his only 3 of the day to Clive Colsell, was involved in a similar tie. At the prizegiving a special prize was given to the competitor from Nottingham who gallantly sailed all weekend without much to show for it in the way of points, although by Monday he was obviously getting the feel of the boat and the conditions, and to everyone’s delight he got 5 points in the 20th heat and 3 in the last one. and this made Chris level pegging with Roger Stollery, who lost no points. The interest in the results of these two boats each round was intense, and everyone looked forward to an interesting sail-off. This materialised at about 3.30, in very good conditions, a near beat and run (a long leg to near the top of 463 It was a very good weekend, everyone agreeing that sailing had been very keen and very fair, and the winds so varied as to test a boat under all conditions. The question now is—what will 10 raters be like next year? Will there be any more developments? (Results opposite)