SEPTEMBER 1972 15p U.S.A. & Canada Seventy-five cents o> HOBBY MAGAZINE

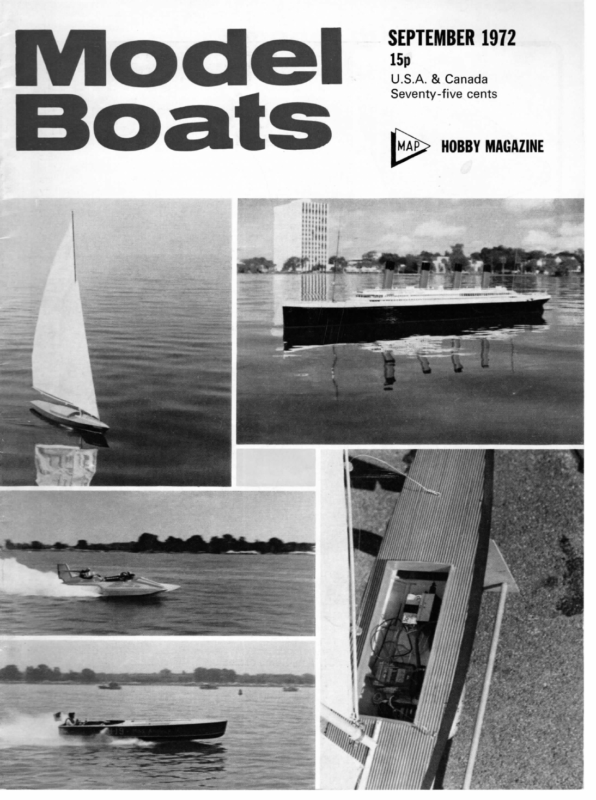

1972 36in. Restricted Championships Fourteen boats from six clubs compete at Cleethorpes REPORT AND PHOTOS BY D. KNOWLES Top, two pictures of Piccolo, the winner, which used a masthead jib and double-luff fully-battened main, both in polythene, Third photo shows Pink Panther, third placer, which is a reduced March Hare. Below, Puddle Thumper, a reduced Longbow, and two Square Ones from Guildford, Whiter Shade and Juicy Lucy. HIS year the Cleethorpes M.B.C. were hosts for the Championship at their home sailing waters at Sidney Park, Cleethorpes, and are to be congratulated for their organisation, enthusiasm and hospitality. More than half the competitors and mates turned up the night before the event and were met by that inimitable duo Harry and Gordon who promptly attempted to destroy all opposition by supplying food and drink (and drink) until well after 3.0 a.m. (The story goes that Harry’s newly acquired Kubernetes ‘A’ boat at one time held three people and 14 pints of Newcastle). The morning of the race was for once this year brilliant sunshine with a top suit breeze and all competitors were booked in and on the water by 9.30 a.m. As the time got nearer 11.00 a.m. the wind strength started fluctuating and the direction wasn’t all that steady. Jean I/I started off on one tack and just before coming in swung into the other tack, then back again by which time she was three parts if the way down the pool. Then she stopped, turned round and beat back to the start. Oh confusion! 11.00 a.m. on the dot O.0.D. Harry Briggs, who sportingly stood down from sailing to organise the event, called the skippers and mates up and decided to sail until half the race was completed before breaking for lunch. The start of racing seemed to find the wind settling down a little but just as we were starting to enjoy ourselves, it started playing up again; the only direction it didn’t seem to be going was straight up. At one time 376

SEPTEMBER Piccolo Jean III Pink Panther Spider Whiter Shade of Pale Mickey Juicy Lucy Sooty Taffy Far Short Puddle Thumper No. Club 1045 1063 372 1064 1060 Bournville Guildford Bournville Guildford Guildford 1072 936 1077 1021 Birmingham 1023 1069 Piglet Cleethorpes 1075 1080 56.5 5 25 0 =3) 5 2.3) ee 5: 0 -0 3 6 32 OS as 5213 Or Leeds & Bradford Cleethorpes 1079 Hot Pants Tigger score Leeds & Bradford Birmingham Southgate Cleethorpes Cleethorpes 0; 3 0: 25:2 202 DeStorAO nc Samer tae 0 0 0 Se55 2-06 ooo) 210 7Oe 5-85 ia SPO 6 66) 5-3 2:55 3)S5Oo) §) 2256s. 00! | 0v67) eoooootUawaaagny Boat 5 Se? by 2 5 6295) 57 43-0 S425 36 6 4- Sar b2te|. =o 64-50 5°26 ed 2 -S7 0 OZ. 5.50 33 0 -20F 5353) 86 200 ON =2) 20. F625 – 0-72 20.” 2 2b es =O -0L.3, 0 3′, 2–5. 37-00. O-:0° 10″ SPOie OF Oa 262s “Be 367-0. OF P2250 Ole 310 10>. Otr2 43 0002 00 0 0 2 2° 50 OF 20°20″ (0). (07-0 23 a7 Pos. Skipper 1st 2nd ord 4th 5th John Lund D, Knowles lan Taylor A. Sinar Alex Austin 1972 G. Danks H. Godfrey S20 57 298th 2 se eStht -20° 10th 19 11th 19 12 13th 5 14th M. Godfrey B. Bull -S;’Gook 2. Briggs G. Griffin Miss Jane Kiddle R. Applegate Only resails involving top three places were sailed. boats at each end of the pool were beating in opposite directions and two in the middle were blown flat by a downdraught. After 7 heats the score sheet was reading Jean III 29 pts., Piccolo 27 pts., Pink Panther 24 pts., Mickey 23 pts., Spider 22 pts., and Whiter Shade of Pale 22 pts., all pretty close so nothing was certain yet. The second leg, after a very good lunch provided by the ladies of the club, started with the wind still top to second suit but with gusts coming at any time and luck was playing its part. Jean III and Pink Panther had one of the most exciting heats with both boats starting off well, then fading and turning round to the start again, then back again on course, finally finishing up with P.P. nosing over the line a bumper in front. By 4.30 p.m. all boards had been sailed and O.0.D. Harry Briggs found that the only resails necessary were those involving Pink Panther who could take 3rd place from Spider if he won them. So with all competitors looking on they took place and Ian Taylor made no mistake about them. The boats varied quite a lot; the trend over the last 2-3 years seems to attempt a prettier boat than the usual efficient machine the Duck. Harry Briggs and Ian Taylor started it last year with Puddle Thumper and Captain Pugwash, both scaled down Witty Marbleheads. Fred Shepherd’s Square One was the other breakaway design, still being well sailed by Alex Austin. The winning boat, Piccolo, was designed and built by John Lund with an attempt to scale down the Marblehead looks without losing any efficiency. It takes full advantage of the 36 in. x 9 in. x 11 in. x 12 Ibs. and makes use of much more than scaled down fin area, which on the short w/l needs to be oversize. Another breakaway was the polythene sails, double luff and fully battened. At all times the spinnaker used was a semi set so that the boat appeared to have two mains, a most effective arrangement for the conditions. A very nice boat, well built and well sailed by John and Ken Maskell. Jean I// is a Duck built in 1957 by Arthur Levison which under normal conditions the writer considers to be still the most efficient type of 36R. Not an easy boat to sail by any means but once mastered is capable of beating anything. Pink Panther is scaled down from a Stollery March Hare by Ian Taylor, who learned his lesson last year and almost doubled the fin area. Well done, Ian. Spider, already a three times winner, is a slightly modified Tucker Windbird and was built by W. Sykes in his usual impeccable style. So once more congratulations to Cleethorpes M.B.C. for running and finishing completely a National! rate than at any time in the near 50year history of the rule. Certainly in the ten-rater class water lines have jumped, but the 60 inch waterline boats Readers Write…. 10-RATER DESIGN Dear Sir, | am sure that the appearance of the lines of Cracker last year created a fair amount of interest, particularly among those skippers possessed of oldfashioned conventional ten-raters. The new design appeared to have all the attributes which at one bound would put them back on par with the top men, Noteworthy points included long length, light displacement, prognathous fin and bulb, fine lines and famous predecessors from the same board. Having appear | tractively watched out was pleased built one at for models to to see an ata recent race. However, its performance caused something of a shock and induced serious second thoughts about going ahead and having one. Its weakest point scemed to be an inability to carry its already limited sail area, as it was on a number of occasions knocked quite flat by gusts, most surprisingly for a 24 lb. boat. Secondly, on the close reaching boards it showed inferiority to at least two if not three of those old-fashioned, conventional ten-raters, and was no better off the broad reach. Most skippers carried spinnakers and the Cracker again badly showed tenderness, _heeling in the gusts. | feel that Mr. were Lewis has got into a snare in designing for the largest spinnaker allowed under the rule. For one thing, just how often does one get a true spinnaker wind, and again, would the boat not go just as fast with a smaller spinnaker aligned with a more conventional sail plan? For four weeks on the trot | have sailed in reaching winds with every prospect, so | reckon, of a fifth and sixth, and owing to the frequency of this condition | suggest that some revamping of the design is necessary to accommodate this. An altogether lower and wider sail plan would seem appropriate in conventional proportions, A _ deltoid fin with a forward-sloping fore edge as designed but with an aft-sloping after edge could help not only by increasing the displacement but improve the boat’s dynamic stability and iron out a tendency to wander and lurch. On another point | have heard a number of model yachtsmen express fear and dismay at the apparent rapid outclassing that has, and if you believe them is, taking place. | say ‘apparent’ advisedly as | think to some extent it has been more apparent than real. To take the ‘A’ class first, | think that the past few years have produced only to be expected improvements and that outclassing is happening at a slower 377 winning championships in the 1950s so it is about time we got up to 66 inches. The change in the rule adopted a few years ago is the de- cisive factor here, as a boat of 66 inches under the new rule gets virtually as much sail as 60 inch boats got under the old. | also think that skippers of those old-fashioned you-knowwhats would do better if they did not get a fit of nerves at the sight of the newest boats. If they just grit their teeth and determine to do well, they might find that they are not at quite the disadvantage they thought they were. As we are all limited to 50 inches of boat in the ‘M’ class we are left only with altering the lines and appendages. Rapid outclassing seems to have taken place thanks to the introduction of bulb keels. Why they should have taken so long to catch on, though, is a mystery to me. | remember years before | took up class boats seeing a drawing of a bulb keel and thinking what a wonderful gadget it was. | could not understand why none of the toy boats | saw did not have them. Now that we have bulb keels, model yachtsmen should remember that new designs are unlikely to completely outclass previous ones. They may im- (continued on page 391)

MODEL BOATS COCHIN EXPERIMENTAL CONSTANT CHINE ANGLE SHARPIE 10-RATER BY R. DUNSTER Ca grew and came about as a result of a welter of ideas, thoughts, observations and other reasons. How it all began is not quite clear, but now that she has been built and tried, not fully, but tried, a few interesting things are becoming apparent. To step back a bit, the Trion series of Marbleheads with a multi-chine hull and various keel configurations pointed out (1) that the hull could be improved — and has been (Fivon — see next issue) Right, Co(2) That one could put between the lead and hull almost chin with M rig and keel. any profile one liked but that it must have a cross Various sectional form compatible with the ballast and hull other keels characteristics. John Lewis also has stated this in his are shown opposite. latest 10R design. : : With these things in mind I have for many years and shipping and unshipping them as a race goes on is a considered building a yacht with a centreboard case and problem which I feel the MYA, IMYRU and other trying different fins and ballasts, but in certain classes national bodies can look into, certainly I don’t consider this is taboo if the boat is raced. The 10R class rules tend it any different from a low ratio rig for the beat and the to allow this to be tried and I feel that if the boat sits to high for the run or vice versa according to conditions, as its marks with any keel configuration then no infringehas been happening in races in UK in recent years and ment of the rule is made. which to my mind does not help the sport very much from To enlarge, this means that the fore and aft CG and the average man’s point of view. What do we do? Carry weight of the lead ballast must remain constant, but its a spare rig up and down the pond or 10-20 Ibs. of lead? vertical height can be varied and this is important, for it Cochin was designed as a single chine hull for simplicity allows a boat’s characteristics to be altered according in building, also there are not many hard chine 10R’s and to the conditions in which she is sailing, broadly speaking certainly not many with as great a beam as Cochin, a deep bulb for strong conditions and a shallow fin for 11.6 in. L.W.L. and 13 in. deck. This gives a very shallow light conditions with a whole gamut of in-betweens. The canoe but very flat sections —- no good in a chop but legality of a skipper turning up with a half dozen keels _ quite good in fiat conditions. In spite of large wetted area PN et ay ap ~ sch and wat size bod a7 post ‘ f Maker P oS. 5 “COCHIN” gat as ne >= va — 1S — ‘ tI 2 ss ~ ~ tS f a Se y ee a — eal — 10 1m = Siere = See — — TORPEDO Sai _WEEL OETA sit. ———

SEPTEMBER 1972 the hull is well balanced and is easily driven and was stitched up Mirror dinghy fashion in 3 mm. ply very rapidly. As the first try she was fitted with a Foxtrot lead keel bolted to an adaptor fitted into the centreboard case with an overall draft of 8 in. — wide beam — shallow draft, heavily raked fore edge of keel — weedy waters — and a 70 in. hoist high aspect ratio suit of Marblehead sails. The mast was positioned as plan and surprisingly enough she sailed very well against other conventional 10R’s, winning the first race entered in lightish conditions, 6-8 knots. There was a slight tendency to heel readily but the mast did not need moving, the trim was right. In the next outing she was fitted with a fin and bulb keel, same ballast weight, rig, and fore and aft CG, but 12 in. draft, and she was a different boat, less heeling, fair to windward, dead downwind, and picked up weed galore. This trial of course could not be conclusive as again conditions were light and I feel that the fin and bulb keels are not so good in light weather as the blade types. Once again the mast only required a slight adjustment to the rake to obtain trim. The next outing, the fourth in the water, was the occasion of the club 10R Championship and this time she was fitted with a Foxtrot type ballast but with a draft © drawing size sheer mes, full- fan, etc.) ass In | Model | Service, = Street, emp stead, 4 of 114 in. Once again light conditions and the same Marblehead rig without shifting the mast and she performed faultlessly, winning the trophy without difficulty. A point noted was ghosting ability with what amounted to a second suit of sails. Tendency to heel was good, she heeled to about 5 degrees and then steadied when heavier puffs arrived. However, as the boat has not been tried in anything above about 6 kts. yet no hard and fast conclusion can be drawn, but as a vehicle to experiment with I think she is very interesting. To date she has 3 keels, 2 blade and 1 fin and bulb, and I will try her next with a prognathous keel, as messing about in the measuring tank with the fin and bulb keel the wrong way round has pointed out what a lot of people already know, this configuration is superior. I might add that I have read up all the info that I can find, but I have not so far heard of anyone who has tried out all the different types on the same hull — no doubt there is someone but, as I said, I haven’t heard of it. The 10R as a class is gaining popularity here in Australia as it is a ‘yachty’ looking boat and is fast but light and there are a number of local designs in being. Last year (1971) there were nine boats entered in the 10R Championship and four of them were original Australian designs and these scored Ist, 2nd, 3rd and 5th, the others being Witty and Lewis designs. In Cochin I am offering a sort of floating test bed rather than a Championship boat. A boat that will give pleasant, HARD CHINE CONSTRUCTION The pictures hard chine struction at right building, by the in gives a clue — 1957! ready break-in for ply a very boat Editor, models, i.e. a show The is a which inexpensive Marblehead method of under con- disappeared, with other at our previous offices, The calendar Cost of the skins, was boat up to framing 30p plus glue, and it stage, would cost only about 50p today. Secret is the use of planed trellis laths, clean, knot-free, and dry, from a hardware shop. These were 3/16 in. x 1 and sawn frame have construction been bottom laths left in. members, are in., in half and still is and were laminated for the backbone laminated for chines and inwales. The clear; Intention leaving available they were was tops locally to so light knock as deck and are out beams. being they could side The used and same in two boats currently being built. 383 docile sailing and should hold her own in average club events. A slight modification to be investigated further I feel is in the skeg and rudder. It is possibly too big or too far aft or too deep or has too long a root length — but here is another area to be examined — any takers? The name Cochin is derived from ‘constant chine angle’,

SEPTEMBER 1972 First Star-C Regatta A very disappointing turn-out FINHE finest, hottest Sunday imaginable, a good what more water, breeze, good organisation— could one want? Well, boats. With five coming definitely and four pretty certainly, and another three at least probably, it was a disappointment to find only three boats competing, and one of those was forced to retire with servo bothers. A fourth boat did arrive, but after sailing for about half-an-hour during the lunch break, found water in the radio gear and dis- appeared. It was, in other words, a bit of a wash-out, which was a great pity in view of the work put in by the Poole club, who had arranged various schedules and had experienced skippers standing by to advise novices on right of way, etc., as they sailed. Fortunately, they had also arranged to sail their Q boats, so the day wasn’t entirely wasted for them. Such sailing as there was by Star-Cs was slightly complicated by a gusty breeze coming through the houses and trees behind the water. There were places where wind flirts spiralled through full circles; the Q boats were heavy enough to get through such disturbed areas with only a slight effect, but the little boats screwed right up and needed rapid sail adjustments to get out of trouble; if the sails are some way off their correct setting for the wind, they will overpower the rudder, which, of course, happens with most yachts. The winning model had a slightly enlarged skeg and rudder fitted, but her builder admitted that in true winds it was very easy to overcontrol the boat. Lack of light tensioning lines and too-small feed holes to the winch drums caused our own model to jam its new (and alas untried) winch more often than not, so that most of the time the rudder was fighting incorrectly fixed sails, making it almost hope- less to sail. Quite obviously, reliability of equipment in these small models has some way to go, but this is largely because the class is bringing in people who are new to R/C sailing and there are bound to be teething troubles as builders try to reduce equipment weight or simply, as in many cases, try to build something like a winch for the first time. The stuck sails and consequent difficulty of con- trol (from which we believe all the boats suffered at one time or another) appear to have given one or two of the Q skippers the impression that the little boats had too much sail for the wind, but we are certain —and we have checked with owners who have other yachting experience —that this is not the case. The original has sailed entirely happily in stronger winds all the time sail control has been available, so a little more time on ironing out sheeting bugs is what is really needed. Incidentally, by request, reprints of the constructional articles on Star-C are now available, price 1Sp post free, or free with a complete set of plans. It is probable that the next regatta for the class (and there will be one, despite the disappointing turn- out for this one) will be on an inland water, preferably easily reached on the motorway network. In the meantime, thanks to Poole Club and those people who did come. Heading picture shows the winning boat (No. 26) at the end of its last heat; the Editor’s model is on its way in, Below, G. Thornhill from Enderby, Leics., with his nicely-built winning model and receiving (right) the very handsome tankard from Mrs, J. Gascoigne, He used R.C.S. radio and a ‘pile’ motor winch, with a worm take-off for limit switches. Under-deck winch drums with large pulleys above deck Ruislip. to lead the sheets. Third competitor was from D. C. Wilkie, No. 17, 389

MODEL BOATS BOATING FOR BEGINNERS Let’s Go Sailing PART THREE — FIRST TIME OUT N the first article in this present series we briefly discussed racing, and last month we looked at choice of a boat. This time we will assume that you have just acquired or built a boat, but before you nerve yourself to approach a club (after you’ve made the approach you’ll wonder why you hesitated) you naturally want to have a go at sailing the model. There are a lot of obvious points which are very much taken for granted by skippers sailing regularly, and whicn are mainly common sense. Experience is still the best teacher. As an example, would you rather stop a 50 Ib. – model travelling at 5 m.p.h. or a 12 lb. model at the same speed? Obviously the lighter the model the less energy, but the water density, ripples, waves, etc. remain the same for either model. Thus a ripple slapping the bow is going to have a greater effect on the speed and/or direction of a small or light model and this must mean that the small model can never hope to sail to windward as easily as a large one. The good skipper thinks about what is happening to his model and tries to reason out why; in addition, he must always be conscious of the wind direction and strength, the effect of any obstructions on the wind, perhaps any current in the water, and any other factors affecting the situation. In other words, he has to be alert and observant, and of an analytical turn of mind. It’s not as bad as it sounds, since after the first few outings it all becomes second nature. Top skippers are divided into the analytical and the intuitive, but both work hard during a race, noting what is happening and balancing the varying factors. As with anything else worth doing, learning how to do it involves a little effort; in the case of sailing a model, the satisfaction of a nicely judged alteration of trim and the sight of the model sailing at its best are immensely rewarding. Pick a day with a good steady breeze for your first outing, since a fitful, swinging breeze will be confusing. It goes without saying that you have already assembled the model once or twice at home and checked that everything is as it should be. Rig the boat at the pondside with the mast in the position calculated by the designer, with the degree of rake that he suggests, or, if it is a second-hand boat, the mast position and rake indicated by the rigging of the model, which will normally show where it has been used to being set up. Be careful to get the mast vertical, looked at from ahead or astern, with the shrouds equally taut. Rig the sails, putting light tension on the luffs (fore edges) and making certain that the jib luff is really taut; it most often hooks to the forestay, so the forestay must be set up hard. Adjust the sheets so that both sail booms make an angle of about 15 deg. to the hull centre-line; it is normal for both booms to remain parallel, or very nearly so, whatever amount of sheet is freed. Have an assistant hold the boat level (or have it level on its stand) and turn it until the wind fills the sails. Now stand away from the 390 boat, astern, and to leeward (downwind) and check the curves formed by the leaches of the sails (Fig. 1). Adjust the kicking strap of the main boom (arrowed) to get the curves as similar as possible. Without a kicking strap, the aft end of the boom is free torise and ‘spill the wind’, so that even a small model benefits from a simple strap, which on small boats can be cord and bowsie (Fig. 2). Note that if a thickish bowsie is used, it should be threaded as shown to get maximum locking leverage. A kicking strap for the jib is a desirable refinement if space permits. Now lock the rudder amidships, by wedging under the tiller or other convenient means, and remove the vane feather or the whole vane gear; in the latter case, to be correct you should substitute an equivalent weight. Even if the boat has no vane gear, initial tests should be with the rudder locked, since they are to determine if the mast is in the correct place. Most people will know what ‘C.G.’ means — it is the centre of gravity, the point through which the weight of an object acts, and obviously it is a point of balance. In a floating object, the force through the C.G. is obviously downward, and it is opposed by the buoyancy of the boat, acting through the centre of buoyancy or C.B. The C.G. is a fixed point, but the C.B can move, depending on the immersed shape of the object, since in fact the C.B. is actually the C.G. of the displaced water. An object (a boat) put into water will automatically trim itself so that its C.B. is vertically above its C.G. This is why it is important to stick closely to a designer’s intentions; a quite small movement of the C.G. will make a considerable difference to the underwater shape of a hull. There are two other centres which concern us closely, the C.L.R. and the C.E. Any sailing boat makes leeway, i.e. it moves downwind while moving forward, and this sideways movement through the water acts through a balance point called the centre of lateral resistance, or C.L.R. If you want, you can find this centre by pushing the hull sideways with a pencil point till by trial and error you find a spot at which the boat moves bodily sideways without swinging. The C.L.R. will be on a line extended below water from this point. The force developed by the sails similarly focuses on

SEPTEMBER one point, called the centre of effort or C.E. Both these points can move, depending on sail angle, angle of heel, etc., but our immediate object is to strike — or ensure that we have — a balance between the C.E. and C.L.R. when sailing to windward with the booms at about 15 deg. Clearly, if the C.E. is too far forward it will push the bow of the boat round away from the wind, if too far aft it will push the stern away from the wind, turning the boat into wind. We can adjust its position coarsely by moving the whole rig fore or aft, or finely by adjusting the rake of the 1972 built true there should be no difference, but there may be a slight abnormality which can be compensated for by a compromise mast position or an allowance of a degree or two on vane settings for that tack. Incidentally, port and starboard tacks refer to the side of the yacht over which the wind is coming, i.e. a boat on the port tack leaving the skipper’s hand will actually be sailing off to his right. The chap who wants to sail seriously will repeat all his tests in differing wind strengths and note in writing what adjustments are needed, if any, in mast position or boom angles. A scale drawn or painted on each boom will enable him to repeat settings accurately. Having established the trim described earlier as ideal, the rudder can be unlocked and the vane brought into operation. Clearly the vane has to steer the boat the tiniest fraction off the wind to sail it straight, and this is termed ‘weather helm’, another slightly confusing expression from old sailing ship days, a hangover, in fact, from tiller steering. “Starboard your helm’ meant move the tiller to the right, which naturally makes the boat mast. So. We put the boat in the water at the leeward (downwind) bank, with both booms at 15 deg. and the rudder locked, point it about 45 deg. to the wind, and release. What we want to see is the boat sail away on a 40-45 deg. course with both sails full and drawing, but very slowly come up into the wind until she loses way, falls a little off the wind, starts to sail again, then repeats the hesitation, etc. This is the ideal trim for the vane, when in action, to sail at its most efficient. What is more likely to happen, especially with a new boat, is that the boat either noses up into the wind and changes tack rather aimlessly, never getting going properly, or it bears off the wind, even to the extent of turning downwind. In the first case, try freeing off the main sheet only and study the result. If an improvement is effected (try more than once, always on the same tack) by having the main notably freer than the jib, move the mast forward, the distance depending on common sense and the size of boat — say 4 in. for a Marblehead. Repeat the tests and the treatment as necessary. If the boat falls off the wind, try the effect of hardening the mainsheet, ultimately moving the mast aft as necessary. It is obviously best to go beyond the required movement and come back to the best position, as in this way you are certain that the mast heel is correctly placed and any further tuning can be carried out by adjusting the rake. This process can take several hours (depending on the size of the lake!) and you will see why a steady breeze is recommended. When you are satisfied that you have found the best position and angle, try the boat on the other tack. If it is turn left. If the boat is on the starboard tack (wind coming over the starboard rail) putting the helm to weather (to the right) turns the boat to lee (left) and, of course, vice versa on the other tack. There are two reasons for weather helm. One is that the boat’s leeway produces slight pressure on the lee side of the fin and rudder, and using the merest shade of weather helm produces a subtle balance against this pressure that makes the yacht instantly responsive. The other is that weather helm enables the jib to be eased the tiniest fraction (the vane stopping the boat from tending to head up into wind) which gives just a little more drive and gets the boat sailing as fast as possible. Sailing to windward is a compromise between ‘footing’ and ‘pointing’. The former is speed through the water and the latter how high into wind she is heading. Trying to point too high is termed ‘pinching’, and the boat will lose speed and make much greater apparent leeway. Freeing off enables her to sail (or foot) faster, and there is obviously a point at which her speed and direction of travel are at an optimum at which trim she will work from one end of the lake to the other in the shortest possible time. READERS WRITE (continued from page 377) prove but at on a the particular expense of point of another. sailing, As in cars, mere newness of design is no guarantee of satisfaction; far better to wait for some other mug to find out all the faults of the design and wait for the designer’s improvements rather than rush in and risk disappointment. Having fired my salvo at the great outnow confidently await enough there | replies (written battleship. please) to sink a A. G. Sheward Hornchurch. Reply to Mr. Sheward’s letter from John Lewis: In response to Mr. Sheward’s letter criticising the design of the ten-rater Cracker, | am bound to comment in order to maintain a balance of opinion. Recently, | received telephone calls from two experienced skippers to tell me that they had seen versions of Cracker racing and that they were impressed. To say that they were enthusiastic is an understatement. Sailing conditions and the boat’s performance were discussed and at no time did the question of inability to carry sail arise, neither was a tendency to wander and lurch mentioned, In fact, top suit was being carried when some other boats had changed down. | have also received letters from owners of this design, both in this country and abroad, and in general they appear to be satisfied. One exception was the owner who reported that his boat had an unusual facility to sail sideways. This phenomenon has not been reported from elsewhere. | can think of a number of reasons why an otherwise satisfactory design could exhibit the faults indicated in Mr. Sheward’s letter but, unfortunately, he does not give enough information to enable one to make constructive comment. In discussions about the sail plan it has been reported to me that the boat is not as close winded as some others in the clas’s. | appreciated that this might be the case but it is a matter of degree and | was prepared to sacrifice a littke windward performance to enhance off the wind speed. This sail plan was designed with reason and care but further sailing trials may indicate that a revision is desirable. Mr. Sheward obviously enjoys sailing on a pool where reaching winds pre- dominate, whereas | am more used to seeing conditions where a beat and run can be sailed. If | were producing a 391 design specially for reaching conditions | suppose it could be different from Cracker, but it would probably be less suitable for general publication. | will not comment on Mr, Sheward’s suggestions for revamping the design, but propose that he tries them out in practise so that they can be evaluated. Referring to sail areas allowed under the revised rule compared with the old one, | checked the area of a 60 inch LWL model designed under the old rule and find that it has 1,236 square inches as measured by the revised rule. This compares with an allowed area of 1,136 square inches for a revised rule 66 inch LWL boat. The 60 inch LWL is allowed 1,250 square inches to bring rating up to 10 by the revised rule, and the older boat could quite easily have had this amount of sail, or more, by the old rule. Perhaps one should look elsewhere for the reasons why designs have changed recently? It is a good thing for the sport that many model yachtsmen are prepared to take calculated risks in the design of their new boats, even though not all of these risks have proved successful. One hopes few people will heed Mr. Sheward’s depressing advice to’. . . wait for some other mug to find out all the faults… .’