APRIL 1973 15p U.S.A. & Canada Seventy-five cent HOBBY MAGAZINE H.M.S. Rodney e Orkney and Shetiand steamer Proportional sail winch

APRIL Marathon (1 hour) on August 25/26th and the Nat- In the Tideway ional Lhis journal has in the past aired a number of controversial issues, where we have felt that the best interests of the entire hobby, or a branch of it, are served by so doing. The use of our pages as a forum to exchange viewpoints has proved valuable on many occasions; older readers may recall the insults hurled some 15 years or so ago, when coherent national radio-control rules for power boats emerged 1973 as a Multi (1 hour) Championships the following week-end, Sept. Ist/2nd. Entry forms are now available for both events; please apply for both at the same time if you are attending both. All inquiries should be accompanied by a large S.A.E. and state which class is required. The Mini-Marathon will be the eliminator for the World Championships which Keighley hopes to be staging in 1974. For very full details, local notes, and entry form, send (as above) to K. Parkin, 48 Park Road, Bingley, Yorks BD16 4LT. direct result of the argument. That series of exchanges If you happen to be passing near Honolulu June 30th-July 7th, the Mid-Pacific Model Yacht Regatta friends. These considerations prompt us to open up a discussion on the extensive alterations to the ‘A’ Class yacht rules which have been proposed to the I.M.Y.R.U. Feelings seem to run stronger on this than on any yachting subject since the immortal ‘keel row’ of the early °30s; lest anyone should think that will be Santa Barbara O.D., 50/800 (Marblehead) and 36/600 (36 restricted with 600 sq. in. sail limit) and there may be one or two others. The Hawaiian hospitality is out of this world, but it’s a long trip there! Dates for Brighton & Hove S.M.E. regattas (all 10.30 a.m. start) at Hove Lagoon are. got pretty heated, but everyone remained good a public magazine is not the place to discuss such a topic, it should be pointed out that the very fact that it is public encourages a letter from the type of chap who feels his voice is otherwise unlikely to be heard. Controversial decisions apparently made behind closed doors lead to bad feeling and loss of enthusiasm, but if someone has at least had a chance to make his particular point to an audience, he is likely to accept with better grace a ruling with which he disagreed. In the belief that these pages offer the quickest and widest means available to express an opinion, we invite yachtsmen to ventilate the pros and cons. Oil Users of Castrol M in home-mixed fuels will be interested to hear that it is being replaced by Castrol MSSR. This is specially formulated for our engines, under the guidance of the firm’s chief executive in Austria, who is a keen aeromodeller. The new Castrol MSSR will be available in quart, gallon, and 5-gallon containers from model shops or can be ordered from any branch of Halfords. Price will be the same as M. Regatta Information Thames Shiplovers & Ship Model Society annual rally at the Round Pond, Kensington Gardens, will be on June 3rd. Programme has been slightly modi- fied to give entrants more opportunity to sail. Entry forms from J. W. Blight, 7 Pageant Walk, Croydon CRD SUG. Classes (all scale, of course), Square Rig, Fore & Aft Rig, Experimental /unconventional, + in. scale Thames spritsail barges, power (electric and steam). Sailing events for Square Rig, Fore & Aft Rig, Fishing Craft, R/C sail, power scale is on. The three definite classes to be sailed (all R/C) April 15 May 20 June 17 July 15 Sept. 16 Multi-boat racing: Classes 0-3.50 c.c., 3.51 c.c., 6.55 c.c., 6.55 c.c. and Over. 20 min. duration. Fee 25p per boat. Steering Event — followed by Multi-boat racing. Fee 25p per boat. Multi-boat racing as April. Multi-boat racing as April. Maulti-boat racing as April. St. Austell D.M.C.~is holding an off-shore race at Mevagissey on April 22nd, starting 9 a.m. Triangular 3-mile course, to O.M.R.A. rules, classes A. B and C. Last year there were 41 entrants and ample fast chase boats, and it should be a good event. Entry forms and details, S.A.E. to D. Wellington, 9 Polwhele Road, Tregurra Lane, Truro, Cornwall. Other O.M.R.A. meetings scheduled are: Clacton, 6th May (D. Harvey, 116 Rickstones Road, Witham, Essex). Canvey Island, 10th June (P. Simmonds, ‘White Sails’, Thorney Bay Road, Canvey Island, Essex). Torquay, 25th July. Organiser yet to be appointed. Port Talbot, 26th August (N. Morris, 17 Eagle Street, Port Talbot, Glam.). Canvey Island Endurance Race, 9th September (P. Simmonds, as above). Port Talbot Endurance Race, date in October to be fixed (N. Morris, as above). The O.M.R.A. is now holding open committee meetings every two months, to which all members and prospective members are welcome and if anyone who is interested would like to contact Mr. Simmonds at the above address he would be only too pleased tc keep them informed of the venue, date and time of the meetings, as they are purposely scattered through- (electric and steam) and barge match. Leeds M.B.S. regatta on July 22nd is all multi and is pre-entry only, entries by July 10th. Entries will be sent a card giving sailing times; long-distance boats are asked to give approx. time of arrival. First heats 10 a.m., classes A 0-3.5, B 3.51-6.5, C 6.51-35. Three 10 min. runs, best two to count, entry 15p per boat, please ask for separate forms for each entry. O.O.D. Alec Midwinter, noise meter in use, 80 dB limit, club will not provide fuel, split frequencies should check ability to run with adjacent spots. Entry application D. Boothroyd, 33 Gipton Wood Ave., Leeds L28 2TA. Swindon SR & Sp. regatta (listed last month), will now be held April 29th. Bournville club will be having exhibition and R/C runs over May 27/28th; anyone who wants to come along is welcome. Keighley D.M.E.S. is running the annual Mini- out the country to allow everybody a chance to visit. There appears to be slight confusion over the National 10-rater Championship which will this year be a three-day event at Birmingham, on May 26/27/28th. A good entry is anticipated and, with three days, it is hoped to avoid the rush to get finished, which often occurs. 1973 MODEL MAKER TROPHY The M.M. Trophy was this year offered to Birkenhead as the major M Class meetings are in the Midlands and Eastern Districts; the Trophy has been S., E., Mid; this year it will be N., and next year, back to Hove. The race is for M Class boats whose skippers have not won a National Championship, Birkenhead have elected to hold it on May 20th. No entry fee, entries by the end of A 143 direct to K. Jones, 8 Marine Avenue, Binmborough, eshire.

MODEL BOATS Clockwork Orange JO model yacht in recent years has caused quite so much controversy as Clockwork Orange, designed by Roger Stollery in 1970 and, incidentally, christened in that year, before a film employing the name was heard of. We featured it on our August 1971 cover, just before the 1971 ‘A’ class Championships, where it made its first major appearance. Comment was mixed, ranging from light-hearted derision to outrage; some thought the boat might make a reasonable 10 rater, and its 11th place in a fleet of 40, with 70 p.c. of the winner’s score, was generally ascribed to the recognised ability of its skipper rather than the boat’s capabilities. There was some talk of it not meeting the rule properly, although it had been properly measured and certificated, but since performance had been a little erratic, the point was not pressed; the Orange was written off as an experiment which did not succeed. Now Roger is a chap who believes that you need to sail a boat for a whole season, or even two, before you begin to get the best out of it — witness his Marblehead Hector, which did little in its first couple of years but then started winning practically everything in sight. In 1972 Orange started to win, in favourable conditions, in club and district races. In the 1972 Championships Roger Cole sailed her, tying for second place until the very last heat, proving that her performance was not solely due to Stollery skippering. She went on to win the International at Hamburg, and it was realised that, far from being a failure, she was a very potent performer. Unfortunately, she does not look like a conventional ‘A’ class boat, and the look of the yachts appears to be a large factor in the enjoyment of a number of the skippers who sail this class; the number of valid certificates for yachts of this class in England is currently 82, incidentally, including 14 new boats registered in 1972. There are very small numbers of boats to the rule in Germany, France, Belgium, Holland, and Denmark, some of which are regular competitors in British meetings, and, of course, there are boats in the U.S.A., Australia, South Africa and New Zealand which rarely have the chance to visit this country. Apart from her light weight, Orange differs from the conventional iin that she has a turtle deck, i.e. no gunwale ‘corners’, as is clear from the lines drawing shown, and she also ‘sails with a wing mast, as can be seen in the photos. As far as we can ascertain, her only departure from the rules is that there is no black band on the mast, above which the bottom of the sail headboard shall not be hoisted. Since in her particular case there is no sail headboard, nor any mast above the sail head on which to paint a black band, there is some difficulty which, however, could presumably be overcome by pushing a pin in the top and painting a black band round it. No one has suggested, to our knowledge, that the boat would sail noticeably less efficiently if her sides were carried up with a fair amount of tumblehome and a conventional type deck fitted, i.e. the designer is not securing an unfair advantage by exploiting a loophole in the rule, so it would appear that objections boil down to opinion on what is nice-looking. Roger Stollery thinks that a pleasing sculptured shape which is functionally efficient is the way to go, while others think that a nice The different appearance of Clockwork Orange (far boat) is shown in this picture of her sailing the conventional type Zerlina at the Gosport Championships last season. These two articles, by the Editor and Roger Cole, were written quite separately. Because of the importance of the issue, both appear. lined deck, or at least a corner on the top edges of the hull, looks more like a yacht. New rules have now been proposed to the I.M.Y.R.U. which would in effect ban the Orange in her present form. These alterations would presumably also affect the Q (or as it is now. the RA) Class, where several Dambusters currently sail; this design also has a turtle deck. The effect would be to outlaw two dozen or more boats, a greater total than actually exists in the two countries most active in pushing the alterations. While we uphold the right of any group of individuals to question the desirability of new developments, or at least departures from the norm, it is a fact that had some minorities had their way in the past, we could well still be sailing gaff rigs with bowsprits and two or three headsails and lead rudders. One might reasonably think that any decision on drastic alterations to rules should therefore be thoroughly aired and discussed and taken by majority vote. In this connection, the I.M.Y.R.U. (which should decide this issue next August) has shortcomings in that a member country with only three or four sailing skippers has an equal vote to a country with hundreds of active sailing members, which hardly allows a majority view to be put into effect; some might say that a major matter should even go to the extent of an international referendum. Feelings run pretty high on the subject. On the one hand are the chaps who like their boats the way they are and feel that their racing would be spoiled by the incursion of strictly functional craft; on the other are those who feel that progress will inevitably bring changes in accepted appearance and cannot believe that, provided the rules are adhered to, this is a bad thing. The gap between the two can best be illustrated by reporting verbatim some of the comments made to us. ‘Some of

APRIL: 1973 CLOCKWORK designed ORANGE by R.STOLLERY opyright of The Model Maker Plans Service 13-35 Bridge Street, Hemel Hempstesd. Herts “a the objectors belong to the “If you can’t beat ’em, ban *em” school’. ‘The fellow is deliberately trying to cheat the rules’. “Model yacht experiments are welcomed provided they’re failures’ and “Why can’t they be satisfied with the 10r and Ms where they can get away with these monstrosities ?’. It is not for us to take sides, but we can presumably make suggestions. Retrospective legislation is unfair and morally insupportable, and the obvious way to compromise is to accept all currently certificated boats but, if the rule is changed, to refuse new registrations not conforming to the new rules. This allows all existing boats to continue sailing but ensures that traditional appearance will not be further diluted, which should satisfy all honest objectors on either side on the immediate question. Whether additional restrictions on a rule which has operated remarkably successfully for fifty years are a good thing for sailing generally is, of course, a much broader issue. Chris Dicks and Roger Stollery produced in 1967 Projectile and Dambuster which, one might say, were boats out of the normal run. They caused some comments but they were not outstandingly successful and so no great stir was created. Chris then designed Emperor, which although very advanced, looked quite reasonably conventional. Then came, as they say, something completely different. It seemed as though English and American minds were thinking alike, as at the same time as Mr. Muller’s Mini A was published in Model Boats, Roger Stollery’s Clockwork Orange was under construction. Both these boats are very light, both being in the region of 15-20 Ib. under the minimum displacement of the rule and thus accepting massive displacement penalties and drastically reduced sail areas. Compare an average normal ‘A’ boat with Clockwork Orange. Average boat LWL 56 in. Displ. Sail Area CLOCKWORK ORANGE and the FUTURE OF THE ‘A’ CLASS by Roger Cole 62 lb. 1,550 sq.in. Clockwork Orange 55-5 in. 36:5 lb. 1,016 sq.in. Clockwork Orange is built in the usual Stollery style, i.e. round section with no distinct deck edge, made by gluing two fibreglass mouldings together along the line of maximum beam. Roger took her to Fleetwood for the 1971 Nationals, rigged in the conventional way with a double-luffed mainsail. She was not over-successful, gaining 11th position. During this championship week the International M.Y.R.U. committee met and decided to ban double- VER the course of the past few years, the Inter- national ‘A’ class formula has received the attention of several designers who have previously concentrated more on the design of Marbleheads and 10 Raters. This in itself can only be a good thing, but because their designs have sometimes been influenced by criteria applicable in these smaller classes, they have produced rather unusual and sometimes radical boats. 145

MODEL BOATS Roger Cole and Clockwork Orange during the 1972 ‘A’ Championships, (Photo: Fred Shepherd.) Class luffed mainsails on ‘A’ class yachts, so on his return home Roger Stollery set about devising a wing mast system for Clockwork Orange. After much experimentation and a couple of disasters with masts that were not strong enough, a thoroughly efficient glassfibre wing mast rig was fitted to the boat and after an extensive tuning programme she was entered for the Southern and Met. District ‘A’ class championship. This race took place in a 20 mph wind which gave a broad spinnaker reach down the lake at Gosport and a close reach back. Thirteen boats entered for the race, but one failed to turn up. Eric Carter’s Sorcerer was blown across the car park before even being rigged and smashed as it was rolled across the tarmac by the wind. Another yacht retired later in the day, after losing her rudder. It was notable that the skippers present who were more used to sailing M’s and 10 R’s were sailing under reduced canvas whilst the locals who sail their ‘A’s all the time were flogging along in top suit. Because Clockwork Orange carried her third suit and was sensibly handled by Roger Stollery and Fred Shepherd, she won the race, dropping only seven points. The next Gosport open race took place under similar conditions, with the wind slightly lighter and more straight down the lake. Again, Clockwork Orange was sensibly sailed in third suit and dropped only three points to win. And so to the National ‘A’ class championships. Roger Stollery was taking the boat to Germany a few weeks after this race and so was unable to sail. I therefore had the good fortune to borrow Clockwork Orange for the big race. For several weeks before the championship arrived, Roger and I spent many evenings tuning Clockwork Orange and my own Scheherazade II against one another. It was interesting to find that when both boats had finally been tuned to the finest possible pitch, there was very little to choose between them. In fact, in light conditions of steady wind strength the heavy boat proved superior. If, however, we encountered a breeze that gave slight ‘puffs’ the acceleration of the lightweight made its mark. Suffice it to say that in a week of championship racing in light to moderate winds, Clockwork Orange proved good enough to gain third position. The same boats gained first, second and third places in the International that followed and the week’s sailing illustrated that the present ‘A’ class formula produces vastly different boats with very equal performances. To win the championship, the Pollahn brothers sailed their 76 lb. Peter Pim superbly well, as did Mike Harris with the 61 lb. Spinaway to gain second place. These three boats, 76 lb., 61 Ib., and 36:5 Ib., show that it is seldom the boat that wins a championship, it is the skipper who makes the least mistakes. I think Mike Harris will agree that the Pollahn brothers made fewer mistakes than he did and he made fewer mistakes than myself. It is all to do with what Fred Shepherd calls ‘the human bit’. Clockwork Orange was next raced by her designer in Hamburg under varied conditions which tested the skipper’s ability to trim his boat accurately, first time, every time. Again ‘the human bit’, or more precisely Roger Stollery’s skill and experience, proved to be the most important factor. In Clockwork Orange the designer has produced a boat that can be built easily by a complete novice and which is capable of a.championship winning performance. Surely this is just the type of boat the ‘A’ class needs. Another vital factor is the weight. In his article ‘A-Class Reflections’, (Nov. 1969 Model Boats) Mr. Eric 146 Shaw says — ‘The cry “too big’”’ has been with the class almost since its inception . . . is this not the time to look again at the ‘A’ class rule and see if some slight towards lighter displacement cannot be evolved?’ results show that this is not needed at present. lightweight concept may encourage husband and bias The This wife crews, and already Gordon Keeley from Newcastle is building one just because of its weight appeal! So with at least eight of these boats either complete or under construction, the prospects would seem to be good for the ‘A’ class. With only fourteen new English boats registered last year, the interest caused by such a boat must really strengthen the class. But, alas, everyone is not happy. There is a great deal of discussion going on at the moment concerning a revision of the ‘A’ class rule. Perhaps I should qualify the word ‘revision’. There is a series of proposals currently circulating which have the direct aim of eliminating the Clockwork Orange and her sisters. These proposals, if made ‘law’, may eliminate the wing mast and doubleluffed sails from the class and more certainly will eliminate the twenty or so round-shaped boats of different designs from any further ‘A’ class racing. I’m afraid that all these things tend to leave rather a bad taste in the mouth when one considers the circumstances. When Dambuster appeared with a roundsectioned hull, eyebrows were raised, but few voiced any serious comments. Also, in the 1970 National ‘A’ class championship, Ricky Hawgood turned up with his boat Advonne fitted with a wing mast which, coupled with his dished foredeck and the lowly position he gained, became something of the week’s joke. There were definitely no complaints about wing masts or any mention of the possibility of the dished foredeck contravening the ‘round of deck beams’ rule. Then along comes Clockwork Orange and the shouting begins. Makes you wonder, doesn’t it?

APRIL Perhaps the main contributor in the ‘Ban Stollery boats’ campaign, for that’s what it amounts to, is Mr. G. Van Hoorebeke, more commonly known to model yachtsmen as ‘Mep’. He has even gone to the trouble of completely re-writing the ‘A’ class rating rules. To systematically pick to pieces his new rules would merely be destructive, and as the aim of this dissertation is to be constructive, I shall limit my comments to one or two points. ‘Mep’ is in favour of heavily is designed with this in mind and a glance at the sections will reveal that there is no gunwale on the hull and that the shape of the sections follows an unbroken curve right round the hull… . If the two halves of the hull are joined at the line of maximum beam there is no tumblehome on either half and therefore the laying up of the glass as well as withdrawal from the mould is penalising round shaped hulls and seems to base his objections on the assumption that the ‘A’ class rule is intended to produce a boat that is aesthetically pleasant. In other words, what most people think a yacht should look like. He states that the parts of the rule that point to this are the freeboard measurement, the limited deck rounding and the sheer being a ‘fair and concave curve’. I quote from Mep’s ‘Final Project-Comments’: ‘These three points have quite no influence upon the speed of the yacht. The care of the rule is an aesthetical one’. Let us look at these three points. 1. The freeboard measurement is surely to provide a minimum amount above water and thus a reasonably sea-worthy craft. 2. The rounding of the deck. This comes under section 2(e) and the rule says — ‘The round of deck beams must not exceed one twenty-fourth of the beam at any point’. Now an old mariners’ rule of thumb for rounding of deck beams to brace the mast properly was half-an-inch in the foot, or one twenty-fourth. Constructional practicality, Mep, not aesthetics! 3. The sheer being a fair and concave curve, is in all probability a device to stop boats with a hump under the mast to get the rig higher. banning of Dambusters and Clockwork Oranges going to help? To those who hold the power to alter the ‘A’ class formula I submit the suggestion that you consider carefully what you are doing, the whole future of the International ‘A’ class may well be at stake. As a closing note, I recently read an article in ‘Sail’ magazine which concerned the world championships of 1972 for the quarter-ton class yachts. This was won by Paul Elvstrom sailing a boat called Bes which had many novel features. By winning she caused a stir among some of those she had beaten but: ‘Bes was not the only racing machine in the fifty-five boat fleet .. . . the others avoided criticism by not winning’. It seems that they have their problems too! speeding up and easing of the building process. Warlord Dear Sir, May I, through these columns, reply to both ‘Fact not Opinion’ and ‘Fuel Fiddles’. Firstly, on straight runners, while this is not my scene, a general view might help, It seems to me that the argument that the extra two runs are mere time-wasters, then to carry it to its logical conclusion, the second two of a three-run contest are not required. | don’t really know how you conclude, Bill, that by having five runs there would be more competitors with equal scores. Shouldn’t the idea be that the greater time a person is on the water, surely the greater enjoyment, and when all is said and done, this is the main reason for a hobby. With regards to the award of additional marks for ‘looks’, surely this will enhance the hobby in general, particularly in spectators’ eyes, and thereby attract more to the hobby. Secondly, | can’t for the life of me understand why people wish to add complications at the start of any new innovation, If a club or group has two containers, for each of the different mixes, and a steward dishes it out in the quantities required by each com- eased. A simplified keel and mast structure can also be achieved if these sections are used in conjunction with a plate and bulb keel .. . . This building of such a boat becomes purely the assembly of a few major components: deck, hull, skeg, plate and bulb, plus of course rig and fittings’. Alan Hankins, a newcomer at Guildford MYC, has illustrated this by producing a Clockwork Orange from wooden plug to finished boat in three weeks. This must be what the *A’ class needs if it is to survive. At present the ‘A’ class exists in only three or four clubs as their weekly racing class and survives in England only because of the annual championship week. It is the other classes, M’s and 10 Raters, which have by far the largest following here, so how long will this minority of ‘A’ class skippers be able to hog the best week of the year? Will there be a ‘take-over bid’ for that week’s sailing by the ‘M’ class in years to come? I would not personally like this to happen as I was sailing ‘A’s for years before I ventured on to anything else, but on the face of things, and judging by the increasing strength of numbers in the ‘M’ class, compared to the ‘A’ class, this may come about. The ‘A’ class needs more people and more boats. Is the Even if we are to suppose that Mep. is correct, who is to judge what is aesthetically beautiful? Surely it is for the individual owner to decide what boat he wants for himself and not the place of a committee to dictate? It is not as if the round section is without a definite purpose. May I quote from Roger Stollery’s article on his 10R Warlord (Model Boats, Feb. 1967). ‘Today when many boats are produced from one design, it is natural to think of glassfibre construction . . . This leads to a Readers Write… 1973 petitor into his own container and receives the cash for same, nothing could be simpler. Now some would say this makes it easier for fiddling, but if someone was determined to _ fiddle, surely the additive could be put in the boat tank before or after filling. Don’t forget, Trevor, that the majority voted for the standard fuel rule, they themselves would be the watchdogs. | am sure suppliers of fuels will provide on a sale or return basis to clubs or groups who require it for a regatta. My own view of fiddlers is that | hope they will enjoy looking at their trophy with their consciences also looking over their shoulder, and have as much enjoyment as the person who wins without fiddling. Can |, as M.P.B.A. President, say to all who want to carry on enjoying the hobby, because, let’s face it, this is the main reason we joined, if you look about, you will find that the fiddlers, sticklers for rules, grumblers, etc., have stayed only a short time happy ones are still with us. Manchester. while the F. Bradbury. SOMETHING NEW? Dear Sir, May |, through the column ‘Readers Write’ suggest two new lines of development for boat modellers. Firstly; in the field of underwater 147 boats, models on the lines of the Bathyscaphe and similar craft. These lend themselves to both scale and semi-scale, requiring minimal extras for working ability or appearance. Initial submersion can be carried out, prior to a dive or sub-surface run, by the operator. This is a boat which | feel lends itself to the Model Engineer exhibition pool, maybe with a frogman in attendance to rescue non-surfacing boats! Full-size craft for consideration are: Professor Piccard’s FNRS2, FNRS3, Trieste; Cousteau’s Diving Saucer; the submersibles: Alvin, Ben Franklin, Deep Diver. | have had some model experience with these, though somewhat limited, but | can say that they have a fascination all of their own. Secondly: a slalom course of gates along a fast stretch of water, and using radio-controlled model canoes, electric or diesel powered, as a Challenge to the enthusiast who wants some excitement, The line to follow would be the practice of full-size canoeists to use the overflow water of locks and weirs to get the right amount of turbulence in the water flow, Again the fast white water of some Welsh do the trick. Wadhurst. rivers might just A. D. Weibel (continued on page 165)

Proportional Sail Winch G. Thornhill describes the winch giving excellent service in his ‘Star-C’ Al the time I first became interested in R/C yachts, it soon became apparent that some form of homemade winch would be required due to the fact that the only commercial ones available were rather expensive and not compatible with my own proportional outfit. A considerable amount of time was then spent research- ing the rather limited published information on the subject. Robert Jeffries’ articles printed during 1971 in R.C.M.E. covering the whole subject of R/C yachting, were particularly helpful and provided a good starting point. (Would it not help other newcomers if these were printed in booklet form?) It was from one of these articles that the method of operation of my proportional winch was chosen. I therefore cannot claim any originality in the principle used, only my particular interpretation. The principle of operation is shown in Fig. 1. The switch control to the winch is via a wiper and P.C. disc. It can be seen that the contact disc is split into two segments separated by an insulated centre strip. The disc is operated by a proportional servo. In this instance the disc was fitted to the rotary output disc on the ‘throttle’ servo. Two copper wires operate in conjunction with the disc. Fig. 2 shows the feedback arrangement to the switch which is driven by 36:1 worm and wormwheel reduction from the ‘pile’ motor output shaft. With my PS3 servo, 54 to 74 turns of the pulley, depending on trim position, were obtained from this ratio. Wiring is straightforward: battery leads — one to each disc segment; wipers — one to each motor terminal. In operation the ‘throttle’ servo moves the control disc from neutral and positions the live segments onto the wipers. This switches on the winch motor and as the sheet drum rotates, the feedback drive moves the wipers back to neutral. The direction of the winch may be reversed by returning the servo to its original position. Since the feedback drive positions the wipers in relation to the disc, this return therefore reverses the polarity of To motor \)) Sheet -_— ii } Wi Fig. 5 shows the layout of my winch. The motor chosen was the Monoperm Super Special ‘pile’ motor. Whilst this is a rather heavy motor (6 oz.) I felt it would provide sufficient power so that if required, the winch could be used in larger yachts (say up to Marblehead size). The pile gearbox provided a compact unit with the facility for changing gear ratios. The final ratio chosen was 72:1. The stalling load on this ratio has not been measured but at 120:1 a 7 lb weight was lifted with ease. The total transmit time using a 4-8 500 DKZ deac is approximately 10 seconds, which I believe is com- parable with commercially available winches. If necessary, to save weight for a ‘Star C’ installation, a lighter ‘Richard’ motor and gearbox could be substituted (perhaps the editor could report his findings on his own mini-Richard motor drive). Rather than create unnecessary complications on my first winch, I decided to couple the switch assembly as a separate unit, as opposed to an integral layout. To minimise power losses through mis-alignment, a Huco coupling was used to connect motor to switch unit. An added bonus is that the side load on the sheet pulley is not transferred directly onto the motor output shaft bearing. The switch assembly housing is shown in Fig. 4. Lack of machining facilities dictated a fabricated unit; 4 in. Tufnol glued together with epoxy resin was used. For additional strength the butt joints were drilled (4 in. diameter) and pinned at strategic points. Again the pins (short lengths of broken fretsaw blades) were epoxied in position. A 3 in. diameter RipMax axle rod was used for the two drive shafts. The 36:1 feedback drive used a RipMax plastic worm/wormwheel assembly. It was originally intended to make the wipers from copper or brass shim, but after problems were encountered in locating a suitable material, I decided to purchase to pile motor Ss Coupling copper wipers | = ~ \ PC Board | Board FIG | SWITCH Monoperm special G aa PC super Insulated LAYOUT pile motor Teor centre strip Hery Botte FIG 3 connections 150 36:1 W/Wormwheel feedback drive | 4 ot FIG 2 a centre tapped battery supply. radeaocoil ee wired pulley Feedback Z| rive~ Motor contacts the contacts and reverses the motor. Switching achieved by this method obviates the need for limit switches and LAYOUT OF Twin | Olly / Motor servo WINCH pulley for sheets —— Wiper contacts . ~ P.C. Contacts epoxied to rotory output disc

APRIL _ a | v2″ a 5/8″ pe —4 | ‘ | 1/4} 1/2″ -#——— 21/8″ bee MOUNT LL — [Vie —+} | | .SERVO/ FEEDBACK oan at yt a 1973 V2″ V4″ 7 aie | Lye — | —- Sig” SWITCH/ FEEDBACK _MOUNT a an” a wiper assembly. A single channel motorised actuator wiper unit was used. The one which was purchased had five wipers with a slot between the second and third. The fifth wiper was removed and the assembly epoxied to a Ripmax gear centre, taking care to align the wiper contacts with the centre of the mounting bush. I decided to retain four wipers — two per motor lead — in an effort to reduce arcing and increase their working life. The contact disc was cut from 34 in. copper-faced P.C. board, using a 1 in. diameter hole cutter. A ~¥ in. strip of copper was removed across the centre using a file and then filled with epoxy resin to retain a flat surface. The disc was epoxied to a rotary output disc, care being taken to ensure that the neutral strip was in the correct position when fitted to the servo. The battery leads were soldered to the centre of each segment on the outside edge of the disc. For additional security, the leads to both the wipers and the disc were also epoxied into position. This was thought necessary to prevent fatigue failure, since the leads move with the switch unit during operation. Accuracy during the drilling of the switch mount is essential to provide correct alignment of the gears and switch contacts. Otherwise, excess free play will result in poor winch operation. A twin pulley was used for the sheets and was turned from aluminium. The sheeting was arranged in a ‘loop’ as in Fig. 5. An advantage of this system is that additional tensioning is not required to prevent tangles. Sheet guides onto the pulley were provided by +4 in. diameter holes in the lid of the sandwich box used to house the radio equipment. On exit from the box lid the sheets pass round two guide pulleys (one wrap around each) and then out onto the deck and arounda pulley positioned aE x| BOW PULLEY FIGS LAYOUT OF WINCH/SHEETING SYSTEM nee GUIDE PULLEYS MOUNTED ON TOP OF RADIO BOX WINCH PULLEY as far as possible towards the bow. The sail sheets are tied to the loop close to the bow pulley. The pile motor and switch assembly were fitted to an % in. plywood base, which in turn was fitted to the bottom of the sandwich box. The dimensions given for my unit relate to a PS 3 servo. Different servos may therefore require slight alterations to these, but this should not be a problem if planned before construction takes place. My own winch has now been used for well over 30 hours sailing and has proved completely reliable. By using the double pulley, early tangling problems have been overcome. Two sheeting failures have also occurred, but these were not attributable to the winch. DAVITS (continued from page 159) The radial arm davit was awkward to use and in an For larger ships a different type of davit was developed, the gravity davit. The two arms of the davit were mounted on rollers which slid down rails, and when the davits were level with the ship’s side, they tilted over to place the boat clear of the hull. The St. Clair as you will see has gravity davits and also quadrant davits. Most of the vessels featured in previous articles were equipped with radial davits. emergency it must have been hard work to swing out the boats. A variety of quick-acting davits was designed to do away with the swinging round of the radial arms. Basically the arm pivoted on its base in an arc at right angles to the fore and aft line of the vessel until the ‘outreach’ was enough to clear the hull. There were two types — one pivoted at the base and was forced outwards by the action of a screw inside a screwed sleeve. The other type had a toothed quadrant at its lower end resting on a rack on the deck, and on the arm was a screwed boss which travelled along a screwed rod. The latter type took up more room as the davits had to be spaced wider than the length of the lifeboat. As before chocks and gripes were necessary for holding the lifeboat When making your lifeboats, if they are wooden make them clinker built even if you only represent the overlap of the planks by carving. Don’t forget the lifelines which should hang along each side in loops — many modellers forget to put these on. If you really want to do it properly make ringbolts and fix the rope by passing it through the ringbolt and the back through the strands of the rope itself. firmly when not in use. 151

APRIL Construction notes. Water cooled head. The copper tubing is annealed and wrapped around a former which has a diameter of about in. less than the diameter of the cylinder head. After the initial forming, anneal the coil again and fit to the engine ensuring good contact on the cylinder head fins. The two ends can be tensioned together with 18 swg copper wire as shown. Throttle. Two types are drawn, type | is to fit engines which have a plain venturi. Type 2 is to fit engines which have a removable venturi insert. Type 1. The 4 in. diameter hole should be drilled first. The intake diameter hole should not be more than $ in. The two 6 BA holes are for two screws which hold the throttle onto the engine. Type 2. The 4 in. diameter hole should be drilled first. The body can then be mounted on a long bolt and the end filed down to suit the venturi diameter. The hole for the needle valve can then be positioned from the venturi. Casting Yacht Ballast A job — the job — which seems the most off-putting to the would-be model yacht builder is casting the lead. Yet the actual casting part is completely simple and the making of a mould requires no particular skill. The whole business is far, far easier than most people realise, at least for leads up to say, 18 lb.; above that the chief difficulty is lifting the container of molten lead. Step one is to visit a jumble sale and acquire a saucepan. One with a pouring lip is best, but a7 or 8 in. aluminium saucepan is fine, since two or three taps with the sharp end of a hammer, supporting the pan between vice jaws, etc., will soon provide a neat lip over which to pour (Fig. 1). Some people have the idea that aluminium melts at or near the same temperature as lead, but this isn’t so. For a long stew, say for melting enough for an A boat, an iron pan is preferable and a grip should be bolted on the side opposite the handle, or even two plates fitted across at 90 deg. to the handle, accepting a length of rod or pipe, allowing the pan to be tipped by lifting up on the handle (Fig. 2). For our 18 lb. limit a normal handle is adequate, provided it is securely attached. The pattern is nowadays likely to be separate from the fin, either a plain bulb or a bulbous plate. A torpedo or bomb-shaped pattern is best turned from a consistentgrained timber; it is quite feasible to use a power-drill as a lathe headstock, supporting the end of the wood billet on a stout nail as in Fig. 3. If as much wood as possible is sawn off first, finishing on the improvised lathe is restricted to very light cuts and sanding. If the billet is glued up from two blocks, a piece of rod could be introduced in the centre with a metal tag in a slot to provide a positive drive (3A). Alternatively, a reasonable ‘bomb’ or other pattern can be carved and sanded by hand. Balsa is perfectly adequate for a pattern of this type, though obeche or lime would be better. For a plate-type lead swelling into a bulb, hand shaping is the only way, as it is indeed for any pattern other than circular in cross-section. The finished job needs painting a couple of coats (shellac can be used) and rubbing down before making the mould: the better the pattern, the less work there will be on the final casting. Now comes a mould box, which needs to be fairly sturdy but can be quite rough timber. Make it so that 163 1973 In both types, a washer of about % in. diameter is soldered to the plain end of the throttle bar. The 6BA hole is used to attach a throttle arm made from =) in. paxolin, etc. Silencer. The extension piece is made from a piece of 26 swg. brass sheet. The size should be determined with the aid of a paper template. An overlap of ¢ in. should be allowed. The brass sheet is annealed and wrapped around a balsa wood former made to the size of the exhaust stub on the engine. The seam is then silver soldered. The } in. holes are then drilled with the balsa wood former in place to prevent the extension piece collapsing. The ‘Steradent’ tube is cut to length and slotted out by drilling two holes to suit the extension piece and cutting the material between the holes out with a sharp knife. The baffles are made and pressed into the tube. They can be epoxied in place if necessary. The extension piece is then fitted into the tube and the completed silencer is wired onto the engine as shown. there is a minimum of about + in. clearance round the pattern. The bottom half is an open-topped box deep enough to accept the pattern up to its widest point; the mould must separate at this level or you won’t get the pattern out. The top of the box is simply a four-sided frame, i.e. no top or bottom. Most people will use plaster for the mould, moulding sand not being easy to come by in most places. Ordinary plaster of paris (from a chemist) is best and should be mixed to a consistency of thick cream, poured into the bottom of the box and the prepared pattern lowered into it. Preparation involves waxing or greasing the pattern, after marking a pencil line at the widest point. Tap the box a little to dislodge any bubbles, then leave the plaster to set — very quick with fresh plaster. Fig. 4 indicates separation points. A is a circle, so obviously any diameter will do. B is a ‘kite’ section and is best cast inverted. C is a plate/bulb and is cast on its side, the best way for any pattern having a large side area. (continued overleaf) TilLeieeLanaaadda

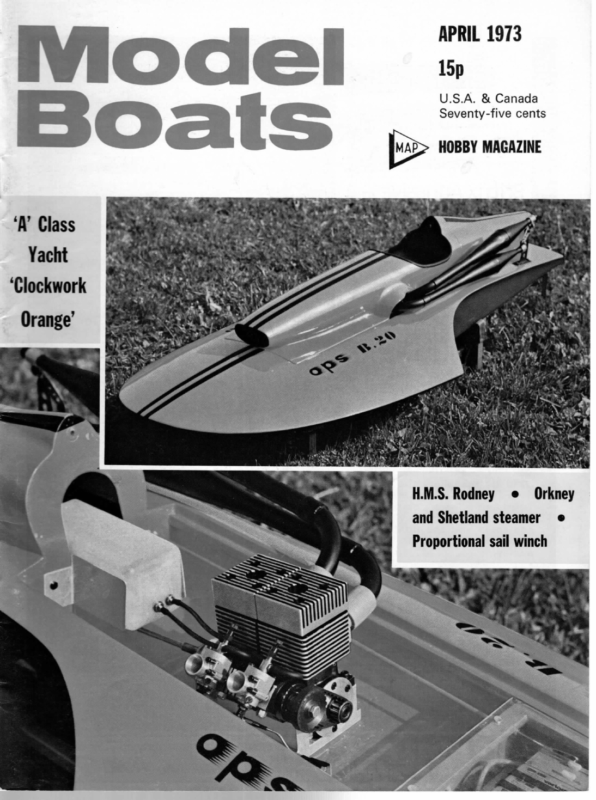

MODEL BOATS 0.P.S. B20 The engine in our cover pictures is quite a machine THWNHIS is a_ limited production 20 ce. twin from the O.P.S. factory, the prototype of which was built for fun by Gualtiero Picco while on holiday. It uses the ABC sleeves, pistons, con-rods, carburetters and pipes of the production Speed 70/73 series (bore 23-85 and stroke 22 mm.) but obviously is much more complex in the crankshaft, which runs on six ball races. A separate shaft provides two induction periods per rev. and thus must run at half main crankshaft speed, the drive and CASTING (continued from previous page) Make a hemispherical key in the bottom plaster by screwing a small coin round in two opposite corners, then shellac the top of the plaster and grease it. Mix and pour on enough plaster to fill the top half of the mould box and leave to set. Prise the top half off and ease the pattern out of the bottom; put a screw in it if necessary, to get a grip. If the waxing or greasing was thorough, and the separation line was at maximum width, it should come out cleanly. If there are any bubble holes, you can fill them, but they will normally only make a pimple on the lead which is easy to scrape or file off. It is important to dry the mould thoroughly, by leaving in a warm airing cupboard for a couple of days or even popping it into a very low oven for half an hour. The reason is that when the molten lead hits it, any moisture will turn to steam and, if there is any but the slightest trace, it can almost explode, scattering molten lead all ways. In Fig. 5 is shown the adjustment needed before casting. It is best to pour in beneath the highest point of the mould, so a ‘runner’ is drilled (about 3/8 in. dia. will do) at X and a pocket is carved (arrowed) into which the stream of lead is directed. It then flows over the edge into the runner free of bubbles and fills the mould, air being driven out through risers at Y and Z. Melting the lead is simple and can be done on a gas ring, an electric radiant plate, or (for moderate quantities) 164 reduction being achieved with a toothed belt on 10 and 20 tooth pulleys. The prototype crankcase was machined from solid in three parts, splitting along the crankshaft axis and again near the exhaust ports, but the short series engines will have a gravity die-cast case in two pieces which offers greater rigidity and will reduce engine weight to around 44 oz. Combustion is alternate to give better balance even over a picnic stove, though in the last case a gas blowlamp is also a help. Clean any old cement, etc., off the lead beforehand; the operation is relatively smell-free unless you are using scrap lead with traces of paint or grease, which will burn off. Cut the lead into small pieces to start the melt; once some has run the remainder soon follows. All the foreign matter rises to the top as dross and is really best removed with an old spoon, although if you have an assistant he can hold a piece of metal strip, etc., close to the pan lip to skim the lead as it is poured. Molten lead holds a lot of heat and will quickly ruin a kitchen floor if splashed. We find it best to set the mould up outside the door and put a piece of hardboard, etc., on the floor, from stove to door, just in case! There is plenty of time to lift the saucepan (using a rag round the handle and/or gloves) and move outside to do the actual pouring. Resting the pan on a brick, etc., helps to pour steadily and smoothly. Pour into the pocket, or well, beside the runner, and pour non-stop till you see the lead rising up the highest riser (Y on the sketch). As the lead cools it will contract and, with luck, the surplus in the runner and risers will be drawn in to keep the mould filled. If you find yourself short of lead, it’s a question of starting again, as newmelted lead, poured on set-off lead, will not bond. Leave for an hour or more to cool, then separate the mould and tap out the lead. Any blowholes or slight imperfections can be filled, provided the weight is adequate.