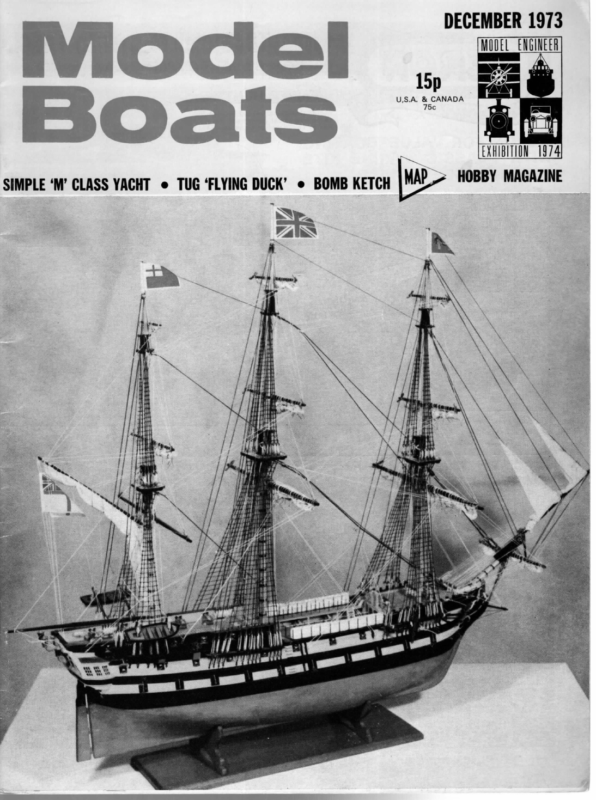

Vicde!l Boats SIMPLE ‘M’ CLASS YACHT © TUG ‘FLYING DUCK’ e BOMB KETCH ~ TT DECEMBER 1973 MODEL ENGINEER 15p U,S.A. & CANADA 75c MAP, HOBBY MAGAZINE

Nee MODEL BOATS GENIE Part One of a series on building a simple and inexpensive 153 Ib. Marblehead yacht for vane or radio BY VIC SMEED rue most popular class of model yacht; vane or radio, is the Marblehead. The basic spécification of 50 in. overall length and 800 sq. in. of sail is some 40 years old, and the class has been international since the mid-thirties. In Britain, the number registered is approaching 2,000, with close to 300 current certificates for vane sailing and a growing number of radio registrations. Model yachting is, more than almost any other, a form of modelling in which racing is an essential part. A lot of people fly model aircraft or run power boats for fun and would never think of entering a competition. There are quite a few who sail a yacht just for the pleasure of sailing, but a much higher proportion want to race against other boats. A Marblehead Owner is more certain of finding competition than one who has an A, a 10, or even a 36, simply because there are more such boats and because just about every club includes the class. A newcomer, then, should look on a Marblehead as a first choice. The objections he may raise may include size — it does seem a fair-size boat, until you’re used to it and have seen the larger classes — but are more likely to be complexity of building. expense, and difficulty in obtaining materials. At this point we uncork the bottle and up pops Genie. This is a Marblehead design which is very simple, quick to build, cheap, made from easily available materials, and yet has a worthwhile performance. If two or three get together to make one each, once the jig is made they can make one hull shell an evening; the wood for the prototype hull cost 30p. The jig is all straight lines, and the original one cost about 20p. Either vane or radio can be used, and the boat has an attractive appearance — quite a common remark from laymen seeing the hull has been: ‘What a lovely shape.’ The design is of the double-chine type but only one joint has to be fitted and full-size templates for the panels are given on the drawings. A straight-sided triangle is used for the hull bottom and this produces a fine entry and a broad flat stern which enables the boat to get on the plane early and stably. An idea of the visual effect of the shape can be gained from the photographs. There is, at present, one major difference in hull requirements for vane and R/C, arising from the fact that a radio yacht does not (yet) carry a spinnaker. To resist the tendency of a spinnaker to push the bow under, many vane boats have full bows, which can slow the boat under other circumstances. A radio boat does not really need so much reserve buoyancy and can therefore benefit from a finer entry. We have A bit on the jury-rigged style, with borrowed sails, temporary mast plugs (look at that bend) and lacking a hatch, the prototype model still showed itself a ‘nice mover’ on early trials. General appearance (top) is pleasing. 510

DECEMBER on pictures two The this page clearly show the hull shape, but conversely they also show how little the somewhat unusual Using notices! shape the natural curves of the timber softens the somewhat stark idea of having so many straight the _ basic in lines construction. Drawings occupy two sheets and part of the second is shown above, to relates since this this month’s notes. For both tempted, those available, are sheets reference MM1175, price £1.10 including V.A.T. and post, from Model Service, Plans Maker Bridge Box 35, P.O. HempHemel Street, stead, Herts HP1 1EE. 511 Uitte oo – o. . > «soil ta 1973

UA MODEL BOATS For yachtsmen who like to see these things, the body plan at left is reproduced. It does not appear on the drawings, which adopted a compromise, but it is possible to modify the bow for vane sailing (if felt necessary) by widening the top of the stempiece O and fading off the width, using tht natural curve of the side planks, through shadows 1 and 2. This would mean a fatter bow above water and is not likely seriously to affect the balance of the boat. An alternative would be to fit ‘applecheeks’ carved from cork or balsa, at the risk of slightly unusual appearance. are structural. The ‘secret’ of the boat’s simplicity is the use of 1/8 in. (3 mm.) gaboon mahogany ply for the hull planks, edge-glued with epoxy and taped internally. This ply is light, softish, and exterior grade, and it is often used for door panels and wardrobe backs. It has a pinky-brown colour and a fairly open grain. Our bits were cut from door panel offcuts, 6 ft. 6 in. by about 5} in., sold very cheaply in the local market. The jig or building board was a dry and true 5 ft. length of blockboard, 34 in. wide, from the same source, and the shadows were cut from odd pieces of 4 mm. ply from the same place. Thus, with a bit of poking round timber yards and the like for ply offcuts, you can have a go ata very inexpensive, simple, and quick-to-build boat. If you were to abandon the project, you wouldn’t be saying goodbye to several pounds and weeks of work; once started, you’ll want to see it finished anyway, and when you’ve sailed it for a season or two and want another boat, perhaps more advanced, or from a glass hull, it won’t be anything like the major step it would seem at the moment. Come on in, the water’s lovely! Consiruction First find some tracing paper (kitchen greaseproof will do) and draw on some straight lines to use as centre lines. Trace off the half sections 0-10 with a soft sharp pencil. Draw centre lines on the ply, turn the tracing face down, line up centre lines, and draw over the lines from the back. Lift paper and go over lines on ply, then turn paper again, lay in place and line up, and again draw over the lines. Since all lines are straight this should offer no difficulties. An alternative is to tape the paper in place and put a pin prick through each corner, then join up the pinholes in the ply with pencil and ruler. Note that nos. 0 and 10, stempiece and transom, are cut from 3/8 in. timber and remain part of the finished hull. The transom (in our case, a piece of secondhand mahogany) is screwed to shadow No. 10 which is cut away so that glue will not come in contact with it. It is important that the transom piece is screwed accurately to the shadow. The stempiece is also 3/8 in. timber and since it is so narrow is best screwed to a triangular support which in turn is screwed to the building board. In the prototype this piece was positioned after the bottom plank was in place, which explains its absence from the photographs. All the shadows now require to be screwed to square or rectangular battens which should run the full width of each shadow in order to stiffen it. Because paper stretches or shrinks in varying humidity and temperature it is best not to trace the batten positions on to the building board but to draw lines at 5 in. intervals. The shadows can now be screwed in place noting that the foreface of the stempiece coincides with the first line and that the afterface of shadows 1, 2, 3 and 4 coincide with their respective Top, the shadows mounted on the building board, and centre, the triangular bottom plank in place. Bottom, side planks in position and chine edge being bevelled. A pencilled guide line just below the cut is a help. 512

DECEMBER 1973 Top, fitting the bow end of one centre plank. The stern is shown in the middle picture; there is no need for quite so much side plank overhang past the transom! Bottom, the second centre plank in oie. Bete use of pins and rubber ands. lines; 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 have their foreface on the lines and 10 is 3/8 in. forward of the line so that the 3/8 in. thick transom matches to the line. The overall true length is 50 in. Be careful to get the shadows truly at right angles to the centre line of the building jig, truly central to that line, and vertical. Each batten requires two screws and since the shell lifts off the shadows it is not necessary to screw from beneath the jig although this method can be adopted if preferred. The edges of the shadows should now be rubbed with a piece of dry soap or a candle stub to prevent adhesive sticking to them. The bottom plank can now be cut and should have a true length of 50} in. (measurement of this on the drawing will give an indication of the degree of stretch or shrink). If it is 4 in. longer at the transom this may be found convenient. Make sure that the long edges are straight and planed clean. This plank can now be laid in place and epoxied to the stempiece and transom. A pin should also be driven firmly through its centre line into each shadow. Now trace and cut the side planks; their curvature is so slight that a little extra length at the transom will not interfere with the fit, and the tracing can be made with a ruler and a series of short straight lines. Cut to leave the pencil lines showing and offer in place on the jig before cleaning up the top edges. Rubber bands hooked from one end of the battens to the other will help to hold them temporarily in place. The top edges (i.e. the deck edges) should rest on the ‘steps’ in the sides of the shadows; it is not too significant if they do not sit absolutely identically down in each and you may have to nick a little off a step if one seems slightly high. The important thing is that the inside face of the ply along the chine edge is not below the corners of the shadows. Once satisfied with the fit, the planks can be epoxied to the stempiece and transom; pins into the shadows help to hold in place. If in any doubt, let the natural curve of the ply guide you, since in any event when the shell is lifted off the jig the deck not, one of the slower epoxies will enable more leisurely working. Pin the planks to the shadows and use rubber bands stretched over, as in the photographs. Leave to set thoroughly. Now comes one of those moments in modelling to which one looks forward. Unscrew shadow 10 from its batten and the fillet from the stempiece. The hull shell will now lift off the shadows and, to your astonishment, prove quite strong and handleable. It will tend to spring inward, so cut a piece of scrap about 10 in. long and wedge it across the deck edges in the region of station 5. At this stage people who saw it were surprised at how light it seemed — only line will be largely determined by the shape nature dictates. The chine edge now has to be bevelled to fair in with the shadows, and we found the best tool for this was a Multicraft knife with a chisel blade (see photo). A very sharp chisel would obviously be equally suitable. Pare away thin shavings; the ply is soft and it is easy to cut inadvertently below the required line. Aim for a smooth, even line with the bevel matching the shadows, and finish off by glass- just over 1 Ib. papering. A guide to the shape of the centre plank each side is given full-size on the drawing, but it can only be a guide. Trace onto card and cut the ‘critical edge’ carefully. Offer to the hull and trim, if necessary, to a neat fit. Check that the outer edge overhangs the hull side panel by about ; in., then transfer to the ply and cut out. The critical edge has to be bevelled to a snug fit against the bottom plank, not a very difficult job, while the outer edge should sit smoothly on the ready-bevelled edge of the side plank. If you are building quickly, use a quick epoxy such as Humbrol ‘five minute’ to glue the centre The next step is to complete the shell by running lengths of 1 in. glass-fibre tape, or strips cut from glass cloth (not mat), along the inside of each of the four joints. Only a small amount of resin is needed for this, but the strips must be thoroughly wetted out. Alternatives which would probably work quite adequately would be 1 in. bandage or strips cut from linen or nylon material thoroughly wetted with Aerolite or Cascamite glue or even varnish; there is less doubt with glass and polyester resin, however. Run a strip across the transom joint and poke the forward ends of the main strips well down in behind plank in on each side — there is time to do it! If the stempiece. From now on construction becomes more conven- tional, but we will be dealing with the whole boat step-by-step in the next two or three issues. 513 mii

MODEL BOATS The Aerodynamics of Yacht Sails By Harry Woodend. Reproduced from the M.Y.R.A.A. Quarterly Report by permission of the Model Yacht Racing Association of America (HE work described here was the basis of a report that was an outgrowth of a series of wind tunnel experiments on sails at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1915 to 1921 and of sundry attempts of Messrs. Warner and Ober to find relations between the performance of sails of a yacht and the wing of an aeroplane. The original report was presented before the American Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers in 1925. The very scientific manner in which the results were obtained from the experiments were later of great value to marine architects and sailors. All work was done while sailing close-hauled. That point of sailing was considered of the most interest aerodynamically, and it was also very much easier to treat experimentally than a reach or a run would have been. Air pressures are proportional to the square of the velocity of the wind relative to the boat, which is only slightly inferior to the sum of the true wind speed and the speed of the boat when on the wind, equal to their difference when running. The absolute pressures would be only about one-tenth as large when running as when going to windward under the same conditions, far too small to be measured with any accuracy. Furthermore, results show that all pressure intensities increase near the luff. The pressure falls off rapidly towards the leach, on the other hand, and in most instances reaches a value near to zero at the last row of points. This is the first significant conclusion from the tests. It is in strict accordance with what would have been expected from aircraft experiences, for it is a fact in aerodynamics that the maximum pressure on any wing or inclined surface is found very near the leading edge and falls off rapidly going back along the chord. The importance of this concentration of pressure near the luff becomes doubly apparent on considering in detail the mechanics of the process by which the pressure on a sail drives a boat to windward. The pressure of the air against a sail at any point has two components, a force acting perpendicular to the surface of the sail and a small frictional drag parallel to the surface. The second of these components being insignificant by comparison to the first, it can be neglected, and the resultant force at every point, whether it originates as a positive pressure on the windward side or a suction on the leeward side, considered to act exactly perpendicular to the sail at that point. This resultant can then be resolved into two forces, one perpendicular and the other parallel to the axis of the boat. Obviously only the second of these components has any direct effect on the driving force. This then is shown graphically, for three points on a typical section of a sail. It is evident from the drawing that the curvature of the sail makes the forward component of force parallel to the boat very small, if indeed it is not 532 < ~* actually negative, for those parts of the sail near the leach. Practically all the driving force must be obtained from the forward components where the sail area is relatively large. The remainder of the pressure has little direct effect, except to assist in the making of leeway. It is then very desirable that the pressures should be increased as much as possible near the luff and decreased near the leach, as they are far more useful in the former position than in the latter. It must not be inferred from what has been said that the form of sail shown is necessarily a bad one, or that it could be improved by cutting away bodily a part of the cloth near the leach and reducing the distance across the sail. Like the trailing edge of an aeroplane wing, the leach of a sail acts to guide the air away from the forward edge and so to improve the efficiency of the surface as a whole. If the rear part of the sail were to be removed, then obviously those pressures of small intensity and of little direct use for driving the boat which it now shows would be transferred to points farther forward on the sail. It is relative, not absolute, distance with which we are concerned and if the rear half of the sail is ineffective, it may be presumed that the rear half of the new form would still be ineffective if the present ne pee to be reduced in breadth by cutting away the each. Mast Interference The second striking conclusion is the result of interference between the mast and the sail. It has been found that both the pressure and the suction fluctuate near the luff of the sails. Immediately behind the luff there is a high suction and a low pressure. A little farther back the suction drops off abruptly and the pressure rises and still farther from the luff, about one-fourth of the way across the sail, the suction comes up to a peak once more, while the pressure falls off to a minimum value at the same point. This is easily accounted for by mast interference. The mast, not being streamlined at all, disturbs the flow of air very badly. There is therefore a region of irregular and eddying flow behind the mast and this extends onto the luff of the sail. It gives a high suction on the leeward side for the air flowing around the mast and, failing to close in after passing, it creates a region of ‘dead-water’ when the pressure is below the normal atmospheric value. On the windward side, on the other hand, the discontinuity of flow prevents any direct impact of the air against the sail or any streamline flow along the windward side. The pressure is accordingly low. After the air has flowed a few inches away beyond the mast it assumes again a streamline on both sides of the sail and it is after the assumption of this steady flow that the second maximum of suction is built up. The intermediate minimum is accounted for by the direct ‘impact’ on the leeward side of the sail of the particles of air which are just closing in after having flowed around the mast. Those particles tend to strike

DECEMBER 1973 Usually the sail of a boat when sailing close-hauled is held with respect to the centre-line of the boat only at the boom and the upper part is free to swing off with the air pressure, setting itself more nearly parallel to the wind. In other words, the angle of attack of the sail increases steadily from peak to foot. The nature and amount of this change of angle have a very against the sail on each side before being straightened away in their streamlines with a reversal of curvature in their paths and the result is, of course, an increase of pressure and a reduction of suction. Going still farther back, the maximum of suction is found. Thereafter the suction falls off steadily in the same way as on the wing of an aircraft. The mast interference undoubtedly accounts for that shaking of the sail near the luff which ordinarily gives to the helmsman his first warning that he is pointing too close to the wind. The sail shakes only important effect. when the sign of the pressure on at least one side of the sail has been reversed and the intensities have been changed so that there is more pressure on the leeward side than the windward side. After the sail has once begun to flutter, the form is disturbed so that the smooth flow over the portions farther back from the luff is broken down. It seems quite likely that a certain amount of rigidity to the sail near the luff, sufficient to prevent extensive shaking at that point, would enable a boat to point higher than now is possible. The use of a number of short battens along the luff of the sail might offer some possibilities if they could be made flexible enough not to interfere appreciably with the reversal of curvature of the sail when tacking, but the flexibility or stiffness would be an awkward one. The importance of the leeward side of the sail is obvious. The maximum intensity of suction on that side is more than twice the maximum pressure on the windward side. Not only is the maximum suction greater than the maximum pressure, but it is found at a more useful point. The pressure falls If the amount of twist in the sail is very large and if the upper part is working at an angle of attack large enough to prevent fluttering the part of the sail near the foot is liable to be at an angle beyond that at which the flow of air ‘breaks down’ and the peak of suction disappears. The jib prevents the loss of efficiency by the mainsail because it prevents the breaking down of the flow. It acts as a guide-vane to bring the air onto the mainsail at the proper angle as the air which has just flowed off from the jib is obviously travelling at a smaller angle to the axis of the hull (the motion on the air being considered always relative to the boat) than is that in the free space above. Therefore the angle of attack is made greater with the jib. Of all the points brought out by these tests, this ranks as the most important. Since the usefulness of the jib in helping out the mainsail is a function of the amount of twist in the mainsail, some attention should be paid to the forces controlling the twist. Obviously, the position of the sail at any instant represents an equilibrium between several forces, some of which are aerodynamic and vary as the square of the wind speed, while others, especially the weight of the boom, are due to gravity, and for a given boat are independent of everything except the angle of heel. The weight of the boom and of the sail itself, combined with the pull in the sheet when close-hauled, tend to reduce the twist, off comparatively little towards the leach of the sail, but, as has already been shown, the leach is ineffective in producing driving force. On the leeward side, on the other hand, the suction on the sail is localised where it will exert the maximum of power in pulling the boat ahead. while the aerodynamic forces tend to increase it. Evidently then, the amount of twist of a given sail on a given boat will increase with increasing wind speed. It follows that the importance of the jib is greatest in heavy winds and also that, of two jibs for a given boat, a high one should be best in light airs and a low Pressure on the Jib One of the most striking features of the results of the tests is the difference between the pressures on the mainsail and on the jib, unknown to most sailors. Probably the most important factor in the high performance of the jib is the absence of any mast interference. Leaving out entirely the effect of the jib on the mainsail, which will be reviewed later, and considering the two sails as contributing separately to the driving force, the jib furnishes more than twice as much force in proportion to its area as does the mainsail. In support of the statement that the mast interference is a primary cause of the low suctions on the mainsail, pressure curves for the jib show no sign of that double maximum and intermediate minimum which mark all of the mainsail curves, but follow almost exactly the form which would be expected on the upper surface of a good wing section. one when the wind is strong, the action of the jib then being needed in front of the lower part of the mainsail only to correct for the difference in angle between the upper and lower parts. The amount of twist in a sail changes not only with the wind speed but also with the size of the boat, even though several boats of different sizes were geometrically the same in form. The wind speed which produces a given lift of the boom and twist of the sail is proportional to the square root of a linear dimension of the boat assuming that the weights of all spars vary as the cube of a linear dimension. The amount of twist in the sail of a 75-footer in a 30 mile wind, for example, would be roughly the same as that in the sail of an 18 foot boat in a breeze of 15 miles an hour. Since the two boats will, on the average, sail in winds of about the same strength, it follows that the usual twist in the small sail will be more than that in the large one and the role of the jib will be correspondingly more important on the small boat. Satisfactory rigs cannot be obtained by geometrical into account. enlargement unless this is taken Finally, as between different types of sails, the Marconi rig undoubtedly permits of less twist in the sail than does the gaff arrangement and the efficiency of the Marconi on small boats is probably due in some part to that fact. Interaction of Mainsail and Jib The next point investigated was the extent of the interference between the mainsail and the jib. The necessity of some investigation of that point was apparent from the fact, upon which all experienced yachtsmen appear to agree, that the performance of a boat is better when the mainsail and jib are reasonably close together than when they are far apart. Assuming that to be true, it is evident that the jib must (please turn to page 537) have some beneficial effect on the mainsail. 533

DECEMBER YACHT SAILS (continued from page 533) force per unit of area, is much greater than that of the In summary, the conclusions may be re-stated - 4. The jib serves to guide the air onto the lower part of the mainsail and prevents ‘breaking down’ mainsail. 1. The leeward side of the sail furnished more than of the flow. That function of the headsail is most important on.small boats and in heavy winds. 5. The twisting of the mainsail, partially corrected for by the presence of the jib, is nevertheless distinctly harmful. It should be restrained as much as possible by the use of two sheets or otherwise. half the driving force. 2. The interference of the mast has a distinctly harm- ful effect and careful study should be given to the possibility of reducing that effect by streamlining the mast or otherwise. e 3. The efficiency of the jib, measured by driving —_ DIFFERENT REGATTA (continued from page 531) ee 1973 the ones with sufficient money to indulge in this class (I chose the word deliberately) and who have the time and knowledge to sort out these very powerful but rather temperamental monsters. One rarely sees a new face, and if one does, it is never a young one. Thus it becomes a closed shop, difficult to get into, and with the bad effect of putting off many who would love to run a multi-boat. Even if one considers the case of the lucky young man who manages to get hold of a good 10 c.c. racing engine, his chances of success, jumping into the class feet first as he does, are slim without a certain knowledge of the game. In the U.K. this knowledge can be gained in the 3.5c.c. class, which is far cheaper, and where some success is more easily found. aly Another argument, and I must confess that it is I want to enjoy myself as well. And here is the point; the little race at Sucé was just as exciting, just as much fun, and more, than racing the big boats. People who had never raced against another boat before tasted the thrills of the sport, and they will be coming back for more! But where? Naviga does not recognise the two smaller British classes, and none of the other French clubs run them. Thus, a lot of potential multi-boat enthusiasts will never know just what they are missing, unless Naviga can be persuaded to change the rules. And for all I know, the same situation prevails in other countries. A lot of readers will no doubt be asking themselves; why is he blithering on about the situation in France, in a British magazine? The answer is very simple. You have got all the experience in the smaller classes, you know it works, and that it is great fun; and you know, I have a funny feeling that our much pretty subjective, is the atmosphere at the FSR events in this country. With the really quite big amount of money invested in a good boat, one seems to have a twofold point of view. First, I have spent a lot of money on this boat, so I shall jolly well have to win, to justify the expense, and secondly, I hope and pray that the darned thing doesn’t get damaged. The net result is a rather strained and cut-throat atmosphere, not entirely conducive to fun, which, in respected Editor, and Mr. Jim King, and a lot of others, would like to see the 3.5 and 6.5 c.c. classes adopted over here. Consequently, any good argument is always useful, and I am speaking from experience, have discussed the matter with a lot of French modellers. So more power to your arm, Mr. King. One thing I do know; come hell or high water, next September will see me back in that little town of Sucé! Probably with a Force 3, the bows are sharper my mind at least, is the name of the game. OK, let’s than Marksman! Think yourselves lucky, I shall only be able to run it once a year. Happy boating. FAIRLANDS VALLEY MODEL POWER BOAT hot favourite for the final. By the end of the second lap our Mr. Stidwill was a good straight ahead and lapped Peter Gomez, the back marker, on his fifth lap. On John’s 21st lap he hit a buoy coming out of a chicane and flipped, a full three laps in front of second place man, by then Jim Pallett. On Jim’s 25th lap his Swordsman came gracefully to a halt, leaving the way open for Ian Folkson to make up two laps to take the lead. He made up the two laps, but hit a buoy in the same stretch of water that had claimed both previous leaders. With time practically up, Mr. Head, a late entry, came through to take up the running, but on reaching the chicane which by now was somewhat of a black spot, had the clock try to win; I know I go out with that intention, but J CHAMPIONSHIPS, 8th JULY 1973 , The Stevenage Aviation and Marine Society held its first official M.P.B.A. regatta on what can only be described as a near perfect day with plenty of sunshine and very calm water. —— ; The event, which was multi racing, with somewhat of a variation on the normal type of multi, was very hotly contested. There were only two classes and in each class competitors had two eight-minute qualifying heats, which in themselves were pitched battles. The two highest lap scorers on each frequency then went through to two semifinals per class. The semi-finals and finals proved to be the highlight of the day and at the end of the 12-minute races drew applause from the large crowd. ; Both finals having in theory the most reliable if not the fastest boats of the day were open for anybody to win right up to the last second. In the Class 1 final Ian go against him. This left us with three boats with the same number of laps which we settled by taking their semi-final performances into account. All finalists received a trophy donated by the Stevenage Folkson went to the front at the half-way stage, after the initial leaders had tangled. Jim Pallett, who made a bad start plus a pit stop, then did a real workmanlike job of cutting back Ian’s lead and beating him by about 10 yards. Credit to both competitors for making it a straight race and not trying to carve each other up, Trevor Skinner, one of the original leaders, did a great job of fighting his way back to third place, but ran out of time. The Class 2 final got away to a start not seen in many events, On the first lap they were separated by the time it takes for six people to throw their boats in the water. Onlookers were sure Bill Isard flicked his boat in off the end of his starting cord! At the end of the first lap, it was Bill Isard, Ian Folkson and John Stidwill, who had done a tremendous 34 laps in his semi-final, and was 537 Sports Council, and first and second place men in each final received £5 and £2.50 vouchers donated by Henry J. Nicholls (Potters Bar), Also all heat winners received a pack of beer each. It is hoped next season to run a championship over possibly three or four meetings with substantial cash ee om oa = AoSecon rane os rir Skinner (Wood Green), 23; 4th, F Gan Furlonger (Kingishers) 5 i ss 1: Ist, evenage), J. ett 4; » (Stevenage), J. 25.4 laps; 2nd, (Mortlake), Stidwi I. 16;: 6th, B. Ne borane May aN © ee (Morita) 34.3: 4th, ¥ aoa ass 2: Ist, J. Pallett ake), Isard (Cypneis), 4;84 om: (Stevenage), weai omez 24.3 laps; 2nd, (Stevenage), I. 17.3;‘ 6th, B. (Cygnets), 15.4; 3rd, J. Melville eonee ne eee ist, B. Isar mets), 14.8 secs.; me (Apologies for late inclusion of this report - Ed.)