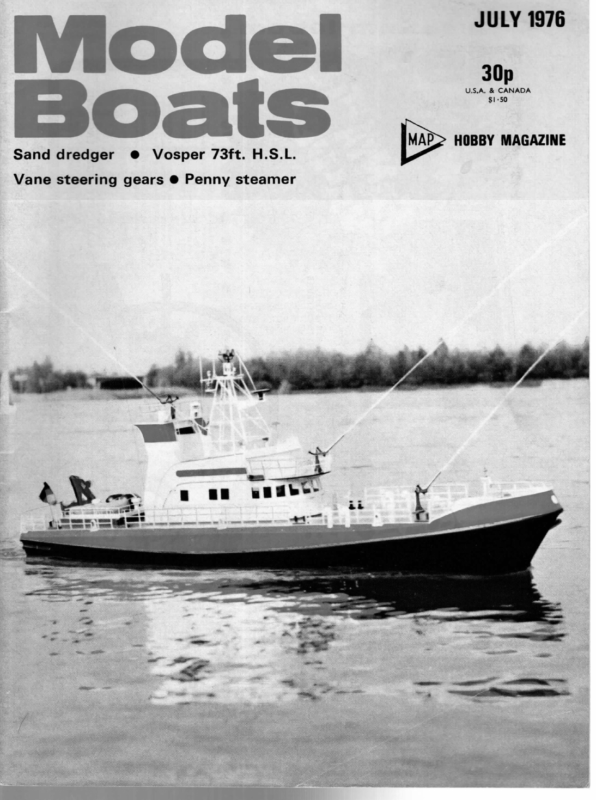

Oa S Sand dredger @ Vosper 73ft. H.S.L. Vane steering gears @ Penny steamer Mi u> HOBBY MAGAZINE

till MODEL BOATS VANE COUNTER-WEIGHT NORMALLY Noes Some notes on FEATHER Vane Steering Gears F SEL SELF RANGE OF _TACKING ACTION 30°-50°: ¢€ OF BOAT a G.1, VANE BODY \ PRINCIPLE OF ,” , BREAKBACK GEAR 2__ FEATHER POSITION ON OTHER TACK by Alan Whiteley Introduction ANE steering gears for model racing yachts come in V a great variety of styles and designs. Apart from one or two commercially available models and a few published designs, they are individually made and reflect the builders’ ideas and experience. By far the most common type in current use is the ‘breakback’ gear, the moving carriage type being, in my observation at least, on the decline, certainly for Marbleheads. I think the reason for this is that the moving carriage gear requires more engineering skills to make and more complicated rigging on the boat to operate it. It is also not easy to combine a moving carriage gear with the increasingly popular synchronous sheeting. _ In the breakback gear, the self-tacking action is obtained by allowing the vane feather to swing relative to the body of the gear when the gear is unlocked. The degree of swing is limited by two adjustable stops which are set to give the vane positions for the two close-hauled courses on either side of the eye of the wind when the gear body is in the central position (Figure 1). In most gears, the movement of the vane feather is linked to the counterbalance arm so that they both move to the same side of the boat. This has the following effects: (a) It assists the tacking action as the counterweight helps the vane feather over as the boat heels on the new tack. (b) It helps to hold the feather on the correct tack against minor wind changes. (c) It maintains the balance of the gear which would otherwise be upset if only the feather moved. This last point is not always appreciated but it certainly contributes to a well balanced gear (Figure 2). Types of breakback gear The many variations of breakback gear can, perhaps, best SELF TACKING STOPS FIXED COUNTER- FIG. 3. PINTLE AXIS—4SINGLE PIVOT GEAR Two pivot gears: Gears of this type have been developed by Roger Stollery in particular. The feather pivots on the pintle axis as in the single pivot type, but the counterbalance arm is pivoted on a secondary bearing forward of the main pintle. The feather and the counterbalance arm are connected together by a simple pin-and-slot linkage so that they both move through approximately the same angle and to the same side of the boat when the feather is tacked. As the feather moves concentrically with the main vane dial, the tacking stops can be mounted underneat h the dial and no additional quadrant or calibrations are . necessary. It is, however, necessary to fit a swing-do wn stop underneath the feather to hit the adjustable stops when tacking, but which can be folded out of the way when the gear is being used normally. One advantag e of SECONDARY PIVOT had a fixed counterbalance arm (Figure 3). One of these designs was published in Model Boats in December 1972. This gear worked quite well and I saw several made by other people. However, for reasons noted above, it was not so easy to balance as those in which the counterweight also moves, although the gear self-tacked and ‘guyed’ quite positively. PIN & SLOT LINKAGE FEATHER~ COUNTERWEIGHT GEAR BODY be classified as one, two, or three pivot gears. One pivot gears: The first gears I made myself pivoted the feather on the same axis as the supporting pintle but FEATHER ARM PIVOTS ON PINTLE AXIS SWING STOP TILLER ARM TM DI PINTLE t ~SELF TACKING STOPS FIG.4A. TWO PIVOT GEA — SECTION R COUNTERWEIGHT FEATHER SELF TACKING STOP \ VANE DIAL CG. OF COUNTERWEIGHT SELF TACKING STOP PIN & SLOT LINKAGE app Lia C.G’s OF BOTH ARMS MOVE INWARDS TO MAINTAIN FIG.4B. BALANCE 384 TWO PIVOT GEAR— PLAN

JULY 1976 COUNTERWEIGHT SELF TACKING QUADRANT & STOPS ON EITHER ARM FEATHER ‘ I 4 XAN Ss GEAR SSA BODY —— ~~ OX Sd NIN —— COUNTERWEIGHT PIVOT i PINTLE AXIS—TM —FEATHER PIVOT MAIN DIAL THREE PIVOT GEAR FIG.5. this arrangement is that the vane body does not have to be accurately centred when tacking, as the tacking stops are not on the moving part of the gear. Three pivot gears: In these gears, the vane feather and the counterbalance arm are both on secondary pivots on either side of the main pintle axis. The two sections are connected together by a slot-and-pin linkage as in the obtained by using a second counterweight in addition to the normal one on the movable portion of the gear. This latter weight is used only to balance the movable part of the gear about the main pintle axis and the secondary weight which is positioned behind the dial is used to balance the rest of the gear together with the rudder plus tiller arm. These two balancing operations should be carried out separately, the second one with the movable part of the gear removed and the boat in the water to allow for the buoyancy of the rudder. When the gear is re-assembled, it should be in balance when set in any position (Figure 6). Guying and over-centring control To make the self-tacking action more positive and to hold the tacked feather firmly against the appropriate stop, an FEATHER OVERCENTRING SPRING O/C SPRINGS HOLDING ea ip STOP BOWSIE two pivot type but as the feather no longer rotates con- centrically with the main vane dial, it is usual to incorporate a small quadrant plate carrying the tacking stops on one of the linking arms (Figure 5). These gears are well balanced and very positive in action but are slightly more complicated to make than the two pivot variety. In addition, the gear must be carefully centred when using the eS self-tacking mechanism as the tacking stops are now on SLIDER the movable part of the gear. The commercially available Jones gear is of this type and has an extra latch which ensures that the gear is correctly centred when selftacking. Another gear of this type is the Fred Shepherd design published in Model Boats in October 1969 (MM FIG. 8. FEATHER os o— BALANCE THESE PARTS SEPARATELY TILLER ARM ‘ =r i PINTLE SECONDARY COUNTERWEIGHT TO BALANCE TILLER ARM & RUDDER =i RUDDER FIG.6. USE OF SECONDARY COUNTERWEIGHT BIAS GUY SLACK — TWIN GUYING SLIDERS ON COUNTER WEIGHT ARMS – PLAN VIEW Gear balancing – SIDE OF VANE BODY FEATHER It is important that a vane gear is correctly balanced for all points of sailing and in both the locked and unlocked (self-tacking) states. If the gear is connected to the rudder by a pin working in a slotted tiller arm, complete balance over the full range of action is not possible as the lever ratio alters as the pin moves along the slot. However, the gear should balance for small deflections of the rudder when the boat is heeled. If any compromise is necessary it is better to balance the gear for beating and closereaching courses when the angle of heel is greatest rather than for a full run. A greater degree of balance can be —_—_~_ =wiRE EYES ON EACH GUY TIGHT S plan 1115 is based on this). MAIN COUNTERWEIGHT TO BALANCE FEATH FIG.7 SS F OVERCENTRING LINE LIDER SPRING OR ELASTIC “| GUYING RAIL ON _- VANE BODY \ C/WT FIG.9. FEATHER? SINGLE GUYING RAIL ON VANE BODY over-centring elastic or spring is usually fitted between the feather and the counterbalance arm (Figure 7). A small bowsie is usually included to alter the spring tension for different wind strengths. In addition to the overcentring line, which acts equally on both tacks, a ‘guying’ control is also required to apply a bias on a preferred tack so that the boat can be made to go about in mid-pond. By controlling the tension of the bias, the offing the boat makes before going about can be controlled within limits and different wind strengths allowed for. There are two common guying arrangements fitted to breakback gears. (a) by two separate guys on either side of the gear, the tension adjustment being obtained by sliders on each side of the counterweight arm (Figure 8). or (b) a wire rail is fitted across the gear with a single slider on it. A spring or elastic is attached between this slider and the counter-weight arm and the guying control obtained by moving the slider to one side or the other as required. In some cases it will be found that this arrangement provides sufficient (please turn to page 395)

AN MODEL BOATS Reflections on yacht SAILS FIG. Wate a lot of thought and development goes into hull design of model yachts, the ‘engines’ of the craft, the sails, do not apparently change a great deal. It seems generally agreed that the sails could be an area where marked increases of performance could be found, but no one ever seems to come out with anything definitive. We have had one or two notes on una rigs (or monosails) and pocket luff sails, but neither type seems to have proved itself superior, under a range of racing conditions, to the Bermuda or Marconi rig which became the norm around 50 years ago. Just in case pocket luffs may have some advantage, they have been effectively penalised by about 60sq.ins. in the recently amended A Class rules, but surely if they were superior in any way, we should see all the top skippers using them in all classes ? Most have tried, but gone back to more conventional sails. Since sails derive power from moving air, the subject is obviously one of aerodynamics, albeit some yachtsmen refuse to accept comparisons between aircraft wings and yacht sails. Certainly the aircraft wing is not expected to run before the wind, but the pressure pattern on reaching and beating courses bears some relationship. When running, the sail is simply blown along, and the only refinements are likely to be in its shape, i.e. its bagginess, to hold the wind as well as possible and extract maximum effort per square inch, and the influence the shape or angle of the sail can have in controlling the direction or attitude of the hull. At the risk of going over recently covered ground, wind gradient should be understood. This is the slowing up of moving air as it gets near the ground (or water) due to friction and minor turbulence. Thus at head height quite a breeze may be felt; squat down and the breeze is less, lie down and it seems almost non-existent. It follows that the taller a sail, the more wind it will catch, which is one reason for tall sails. Unfortunately, the taller a sail the higher its centre of effort, and in the case of a yacht running, a high CE tends to push the bow down. With a vane yacht a spinnaker can be rigged to lift the bow (as well as add much more drive, of course) but radio boats do not yet carry spinnakers. It will be seen that ideally, from a trim point of view, a low sail is preferable to a high one for running, but in conditions of marked wind gradient, the low one could lose in drive. On the other hand, as will be discussed, a tall sail is likely to be more efficient on other courses, so that for radio use, where the yacht sails all courses non- stop, a compromise, or an acceptance of less than the ideal for part of the circuit, is necessary. Spinnakers have been rigged and stowed by radio, incidentally (with a higher success rate for setting than | 4 Le —$<—<——<— Chang of C.P. e (C.E.) from change of flow. Ib stowing!) but with a downwind leg of perhaps only 20-40 seconds, by the time the spinnaker is up it’s time to haul it down again, and the general feeling seems to be that it’s better for the skipper to concentrate on his positioning etc than spend time with a dubious benefit. Double-surface jibs which blow apart downwind but act asa single double thickness sail otherwise have also been tried; again, these would be seen more frequently if they offered advantage, but it seems that loss of efficiency on the wind offsets any gain off the wind. On the ‘aerodynamic’ courses, beating and reaching, an aerofoil section could be an advantage, but we need the same section on either tack. We thus have to use a symmetrical section aerofoil, or the conventional type of sail which can assumea single-surface aerofoil shape on either tack. The former has been tried on a number of occasions, and it works, but not as well as conventional sails. This is probably due to the fact that we are in the area of lowspeed aerodynamics; it is no coincidence that successful very lightweight model aircraft use very thin, highly cambered aerofoils (Figure 1a) with a flight speed of perhaps 15 mph, while ultra-lightweights use single surface wings (Figure 1b) SER ee FIG. 4 An aerofoil has a centre of pressure, through which its lift acts, which moves according to its angle of attack, forward for increased angles etc. Each section also has coefficients of lift and drag, which have optima at certain angles of attack and which vary with the degree of camber of differing sections. The centre of effort of a single sail must lie on the centre of pressure line, but if we alter the angle of attack, by adjusting boom and vane, and/or the camber, by putting more or less flow in the sail, we are altering the CE, the C, and the Cp. Flow, i.e. camber, is increased in lighter winds because very broadly, the lower the airspeed, the greater the camber needs to be to maintain a high C,. The importance of well-cut and well-set sails will begin to be apparent from this, and it may also explain why a good skipper knows what flow is needed for best results on a course in differing wind strengths. Because change of flow can alter the CE, a degree or two more or less on the vane or radio rudder trim may be necessary; changing to an ill-matched second suit (where the CE may be in the same vertical line when calculated by sail area, but because of a widely different point of maximum camber, in practice a couple of inches out) may produce a complete change of behaviour. From low-speed aerodynamic tests, it would appear that the best lift/drag ratio is found in aerofoils where the maximum camber point is between 30 and 40 p.c. of the chord back to the leading edge. This accords with sail practice, where the maximum depth of flow is often FIG, 2 - i. FIG, 3 398

JULY 1976 intended to be on the 30 p.c. line. However, frequently the sail is cut so that this line runs parallel with the mast, which with a triangular sail means that the section gets progressively less efficient than it could be, the higher it goes. Often, too, the sail is cut and stitched in such a way that it simply has a belly, and the kicking strap is used, sometimes in combination with bending the mast, simply to produce a hollow side to the sail. This looks nice, but is not necessarily efficient. The fact that adjustments to the set of a sail can be made by varying tensions on different edges is a powerful argument in favour of modern sail materials. The inability to vary the set to quite the same extent may be one reason why pocket luffs do not have the advantages that might be expected. It is, however, essential to have a well-cut and sewn sail initially, and we could well get to the stage of making a thin plaster mock-up of what is required and ‘building’ the sail over it. Though there are limitations on batten numbers, lengths, and positions in some classes, no development has taken place with fully-battened sails, which have been suggested as more efficient because of the ability to hold a required aerofoil better. Even in the classes with batten restrictions, there is no bar on seamed, panelled sails, which may well offer a line of exploration. With low pressure on one side of the sail and high pressure on the other, there is (apart from the necessity of an airproof sail material) a ‘leak’ under the boom from the high and low pressure, giving a downward movemen t of air on the hp side and upward on the Ip. These opposing streams meet at the sail leach to form vortices, increasing the drag considerably. Since the rules (in someclasses) ban booms of a sufficient width to block the flow, a reduction can only be effected by having as short a foot as practical ; a short foot means a tall sail to use the allowed area, anda tall sail is also advantageous in wind gradient. A tall, narrow sail (high aspect ratio) is more efficient, therefore, than a short wide one (low aspect) but the price is a higher CE and therefore a greater heeling moment. The bulb keel, by producing a more powerful righting eer offsets this, hence its widespread use in modern oats. There has been a tendency to use very much larger jibs in recent years, sometimes with disappointing results. Could this be because a long-footed jib has a lot of pressure leakage leading to leach vortices which, on close- hauled courses especially, interfere with the pressure pattern on the mainsail? There is talk of the ‘slot effect? between the jib and main on close-hauled settings. This is a bending or deflection of the airflow which is caused by the shape of the sail and means that the airstream changes direction by two or three degrees; theoretically the main sail should be working at a corresponding lower angle of attack, in a smoother airstream. Obviously if the jib is 20 ee a BEG = = SLOT EFFECT (exaggerated) Als FIG. 5 creating turbulence the mainsail efficiency is lowered rather than raised. It is interesting to recall that a slot on an aircraft is very small in comparison with the wing chord, yet it smooths the airflow, increasing lift and delaying the stall. Would something like a venetian blind slat up the leading edge of a sail produce greater efficiency than a conventional jib? Again, experiment would have to be limited to 36R or 10r classes, since the others limit the jib height and such a slat would probably have to be classed as a jib. Monosails, or una rigs, seem to offer good results for R/C boats on reaching and running courses, and compare reasonably on beats. Where they may lose is on time to turn, especially in light winds, where there is no jib to help the bow round. If the slot effect of a jib is being used, the conventional sail arrangement may give more drive on close-hauled courses. A monosail should have a theoretical advantage if it uses a buried mast, since a mast is an interruption to the airflow if it runs up the luff of a sail. Which then brings in the question of whether a thinner mast (less interference) which needs staying for stiffness (more interference) is better than a thicker mast with far less staying. Is it worth the weight of a mast mounted at the stern, raked well forward, with jib and main (or monosail) suspended by wire stays from masthead to deck? David Robinson’s Pabri was a recent example of this, but he’s now back to a more conventional rig. “Back to a more conventional rig” is a phrase which applies to almost all skippers who have tried experiments in improving sails. The only spectacularly successful experiment was the Blick/Stollery wing mast on the Warlord 10 rater, but this led to a hasty change to stop what was felt to be a loophole in the rule. Measuring the mast profile as part of the sail area seems to cancel most of the advantages of such a mast. In 50 years of refinement of the Bermuda rig, it seems that, square inch for square inch, it is a difficult sail arrangement to improve upon. Published results of any experiments, failures or not, seem the most likely way of making progress, but in the meantime, more attention to conventional sailmaking seems the more certain racewinner. ‘A’ CLASS TEAM CHAMPIONSHIP (from page 400) The resails were taken over a two hour period and the final result was as follows: 1. Birmingham 2. Clapham 3. Dovercourt 4. Bournville 5. Fleetwood 6. Wicksteed Caprice Alberta Havana Womble Ricochet | Mandator Invicta Dandy Big Brother Longshot Kami Sama The Streak Maverick G. A. Webb V. Bellerson R. Seager J. Hyde G. Bantock A. Lawaman H. Dovey M. Harris D. Priestley A, Lamb C. Colsell E. Carter 39189 points 50 39 |. 83 points 44 f (after sail off) 45183 points 38 f (after sail off) 39 | 82 points 43 46) 74 points 28 37 \. 69 points 32 a Finally, a mention for Bill Akers, who appeared not to sleep — he put the flags, buoys, windsock and catwalk around the lake, with the help of his son Nigel, at some unearthly hour on Saturday and Sunday and collected them all up again at night, as well as marshalling sailing pairs on both days. John Allen was OOD, ably assisted by ‘Pop’ Dicks. Scoring and preparation of start schedules was carried out by Bob Beattie — thanks, Bob. Other members of Birmingham club carried out umpire and starting duties at various times during the weekend.

Ja: l MODEL BOATS Some idea of the conditions is given by this photo of nine of the boats - the one finished, on the bank, was no doubt feeling slightly smug! The three nearest boats are Big Brother, Mandator and Longshot. The ‘A’ Class National Team Championship Witton Lakes, April 17/18th 7 Six teams but little wind, reports Brian Bull : | Tees winds mainly from the South West welcomed the six teams gathered for this particular event, held at Witton Lakes for the first time. All the well-known boats with their equally well-known skippers and mates were given last minute instructions by the OOD, Mr John Allen. At 10.00am on Saturday morning it was intended to sail the full card but the position would be reviewed on the Sunday afternoon at around 4.00pm. Sailing commenced shortly after 10 and continued without much incident all morning, which was quite something considering the wind was Out over the boathouse and left the run start in comparative shelter. The wind did have the skippers on a ‘piece of string’ with its shuffling around, first one side and then the other side of the boathouse. Saturday afternoon was very much the same as the morning except one skipper who was sailing very well — he said it must have been the beer! At the end of the first day the team members’ individual scores were comparable with the team mate and the team scores at the end of the first day were: Dovercourt 57 points; Bournville 56 points; Clapham 53 points; Birmingham 51 points; Fleetwood 45 points; Wicksteed 38 points. It was still anybody’s race! During the Saturday night/Sunday morning the wind had a ‘tantrum’ and decided to ‘blow’ from the opposite end of the lake in North West; what wind there was needed a stretcher and an oxygen tent to help it down the lake. Still, the sun was shining. Sunday, it seemed, was to be the day for resails, and Graham Webb collected eight. Sailing started some time around 9.00am and each board was taking about an hour to complete, excluding resails. After the lunch break, during which the wind did blow up a little, it was in- creasingly obvious that the championship was not going to be completed, but the skippers wanted to sail on to the bitter end. However, after a short consultation the OOD decided that the resails, all seventeen of them, would be taken and a result declared. The resails had in fact created an extremely vague picture of the current position. (please turn to preceding page) Top, winning team member and top-scoring boat Alberta sailing Big Brother. Centre, the other half of the winning team, Caprice (far boat) versus Ricochet. Bottom, Invicta against Kami Sama. 400 a — rics 2

JULY Round the Regattas A general scene from Tameside’s successful R/C regatta is shown right. Winner Barry Jackson fourth from left seems to be guarding his flask. Below runner up Squire Kay prepares to sail 7.D. By the time this is published, we may have seen how his Sea Horse design compares with southern boats at the RM Nationals. (Photos K. D. Sharp, Studio Norbury.) Tameside RMs, 28th March An open RM meeting organised (as a first major event) by the eighteen month old Tameside Radio Model Yacht Club at Stamford Park, Ashton-under-Lyne, on 28th March, drew 28 competitors and was an unqualified success. The club, which is a member club of Tameside Sports Council, was invited to stage a function as part of the annual Tameside Festival. After a schedule of 33 races, B. Jackson and S. Kay were tying on 82 pts, and the former won a very close two-lap sail-off. OOD was C. Thompson, assisted in scoring by Mrs Thompson. . D. Griffin . E. Bertheir 16. N. Leventon 7: S. Ancliffe Midland District M Championship, Bournville, 4th April Seventeen boats entered this year’s race and included the rare treat of two boats from Nottingham. Four boats came down from Cleethorpes. Lord Vulture’s arrival gave the race a regal air and during the day some of the entrants were serenaded with some lyrical examples from the ‘Vulture Songbook’. A strong breeze from the Bristol Road end ensured a good race although it did shuffle round after some indecision to a little less than Northwest. The strength remained and the sunshine added that little extra for a pleasant day. Dennis Lippett was in charge of the well-run race, which started at about 10.15am and apart from the half-hour lunch break continued till about 6.00pm. A number of runs were quite spectacular with some of the yachts moving very rapidly, almost planing from the start to the finish flags. The windward leg was not so simple. The fleet sailed tack and tack all day, which meant for the ‘mateless’ skipper a lot of running — still, it keeps you fit! As usual two or three skippers sailed consistently through the day and most that did well early on fluffed it in the afternoon or vice versa. At the end of the day the top half dozen were very close. A great day had by one and all present, and thanks are due to Bournville for organising the race. Final scores and positions were as follows: Skipper 1. M. Harris 2. G. Webb 3. R. Etheridge 4. M. Dovey Boat Club Jester Birmingham Ax Tung Nothing Yet No Name Score Bournville 63 points Bournville Bournville Ly 3 59 ah 403 mnt Hh Imagination L.O. Sailor Luncheon Vulture Sula Sky Diver Lady Brenda General Synopsis Blue Streak Ship Kris Kolumbus Major Clanger Haughty Vulture P.E. Bournville Birmingham Southgate Bournville Bournville Cleethorpes Cleethorpes Birmingham Birmingham Cleethorpes Nottingham Cleethorpes Nottingham 1976

ee ae MODEL BOATS Midland District RM Championship, Cleethorpes, 25th April Eastbourne Silver Ship On 11th April one of the highlights of the Eastbour ne and District MYC, the Silver Ship Competition, was held, but this year it was an extra special occasion when the An encouraging but cold wind from the North East heralded the start of this race organised by the officers of Cleethorpes. That wind must have come by ‘Red Star’ ee from Norway or whatever else is across the North event was combined with the Metropolitan and Southern District 10r Team Race. With excellent weather and a ea. Force 3 wind, which was SW for the start and later veered to SE, the four competing teams provided spectator s with a very keen and exciting day’s sailing. Seventeen boats actually started sailing out of an original entry of 21. The race was not held at Sidney Park but at a boating lake down Cleethorpe’s Sea Front opposite a pub — nice one Gordon - very pleasant and of good size for radio yachting. The course was an interesting The very attractive Princes Park Lake, together with an efficient band of officials supplied by the host club, ensured a smoothly run competition between teams from the Model Yacht Sailing Association represented by G. Hallums, 1855 Force 10, and J. Hallums, Jsotope, 1885; London MYC, T. Gurr, 1854 Appletree, and C. Parsons, 1821 Katchup, Hove & Brighton, D. Daly, 1851 Hiccup, and R. Conway, 1812 Overture, and Eastbourne, P. Humber, 1741 Madaleine and R. Burton, 1750 Golden Sceptre. Results — Silver Ship — 1. Hiccup 28; 2. Golden Sceptre 18; 3. Katchup 17; 4. Madaleine 16; 5. Appletre e 14; 6. Isotope 11; 7. Force 10; 8. Overture 6. Team Race — 1. Eastbourne 34 plus 17 on resail; 2. Hove & Brighton 34 plus 3 on resail; 3. London MYC 31; 4. MYSA 21. The visiting teams were entertained to lunch in the clubhouse by Hon Sec N. Sylvester aided by his wife and Mrs Woods, to whom thanks are due, as they are to those one set out by the OOD, Albert Pidgeon — not the usual triangle for Albert — it was a sort of ‘X’ shaped, but it appeared to be well liked, judging by the favourable comments made by the various entrants. Graham Thornhill was sailing superbly well and gained maximum points for the day’s sailing. David Andrews also sailed well and only dropped points to Graham Thornhill, as did Steven Benn, who kept them company at the pole positions. The remaining skippers did well, although some were having problems with the strong winds — obviously used to quieter times inland. Racing started at about 10.30am and with the wind being so strong the race was completed by 3.30pm. All entrants did their fair share of judging and there were no complaints when a skipper did something naughty and was caught at it. Two yachts withdrew during racing due to either gear coming adrift or fittings breaking through strain. A great day was had by all — Gordon Griffin kept score and called everyone up. Dot Griffin kept the tea mashing. Albert Pidgeon was OOD and kept a tight race, and a number of Cleethorpes members assisted, with repairs or advice. Thank you Cleethorpes. Final scores and positions: Skipper 1. G. Thornhill 2. D. Andrews 3. S. Benn 4. G. May 5. E. Andrews (Mrs) 6. J. Mountain 7. A. Driver 8. R. Morrison 9. G. Golightly 10. M. Colyer 11. 12. 12. 14. 15, S. Shorter P. Gilby K. Jamieson S. Colyer P. Smith J. North S. Bennett Boat | Charisma Ax-em Minimoa Red Devil Teazle Sweeper Snowflake Push Off Mrs Golightly Aquarius II Pirate Red Marken Pete I Pelorus Jack Isky Club Score Leicester Leicester Leicester 72 points 24 Sa tel 66 Tameside Leicester Birmingham Tameside Tameside Cleethorpes Leicester Tameside Cleethorpes Tameside Leicester Leicester Lincoln Tameside other ladies who provided additional refreshment for tea. The Eastbourne Club have also recently played an active part in “Eastbourne Leisurexpo °76’, a two day exhibitio n staged at the Winter Gardens, Eastbourne, and sponsored by the local Rotary Club. Their display of three fully rigged model yachts, an ‘A’ class, 10r, and a Marblehead, together with a Marblehead under construction, complete with its full scale plans, created widespre ad interest among the excellent crowds attending this very popular event. Dewsbury MMS The first regatta of Dewsbury MMS under its new name (previously Ossett & Horbury) was held on 25th April. Due to lack of water at Crow Nest Park, Dewsbury, the 60 54. 52 SOF 48 32). 50: regatta was held at Wilton Park, Batley and thanks are —C«, ,, | due to the Leisure Services of Kirklees Metropolitan Council for permission to use Wilton Park at very short notice. The weather was fine but cold; wind did not discourage an excellent attendance for the now popular Multi. The results are as follows: Straight Running for the Crow Nest Trophy — Ist Mrs E. Whittaker (Dewsbury); 2nd H. L. Senior (Dewsbury); 3rd J. Humpish (Heaton & District). 25 Minute Multi — Class A — Ist H. L. Senior (Dewsbury); 2nd P. Rawlinson (Halifax); Class B — Ist R. Brown (Leeds); 2nd J. Brown (Tynemouth). Class C — 1st M. Fisher (Leeds); 2nd G. Brooks (Sheffield). 2-5 Kilo Electric — 1st H. L. Senior (Dewsbury). ,, bs 5. 24 .=«C« , 22 22 = 20" %, G6 be Withdrew Withdrew Coventry MBC The Coventry Model Boat Club held a multi-boat regatta at the Wyken Slough, Coventry on 4th April 1976. The weather was dry and sunny but with a light cool breeze. Some 57 boaters entered, from nine clubs, with a total of 108 boats of which 45 were A Class, 36 B Class and 27 C Class. There were 11 races of 30 minutes each and with 11 boats in some races there were very few radio problems, though there were two disqualifications for hitting the rescue boat. After a pleasant day’s racing the club’s President Mr Ian Smith presented the following winning contestants with trophies: A Class: Ist F. Martin (Swindon) 72:1 laps; 2nd R. Burrell (Bournville) 70-0; 3rd V. Hadley (North Birming- ham) 68-3. B Class: Ist R. Burrell (Bournville) 80-4 laps; 2nd D. Horton (Swindon) 72-0; 3rd H. Callow (Telford) 71-4. C Class: Ist K. Rees (Telford) 86-3 laps; 2nd T. Cann (Leicester) 80-6; 3rd A. Arbon (Telford) 73-2. TEST BENCH (continued from opposite) No. 9, Naval Armament, at £2.95 cased or £2.25 pve limp bound. Each is about 240 pages 7 x 44in. with photos and details, including dimensions, history etc. No. 9 has obvious advantages for modern warship modellers of any country, while as a history of submarines, undersea enthusiasts will enjoy No. 8. Publishers are Macdonald & Jane’s, Paulton House, 8 Shepherdess Walk, London N1 7LW. Finally, an enjoyable read as well as a useful history is Gunboats on the Great River, by Gregory Haines, Macdonald and Jane’s, £4.50. A slightly garish dust jacket, but good solid stuff inside, and anyone interested in gunboats in China (the RN on the Yangtse) will find the narrative style easy to get along with and the facts clearly presented. 404