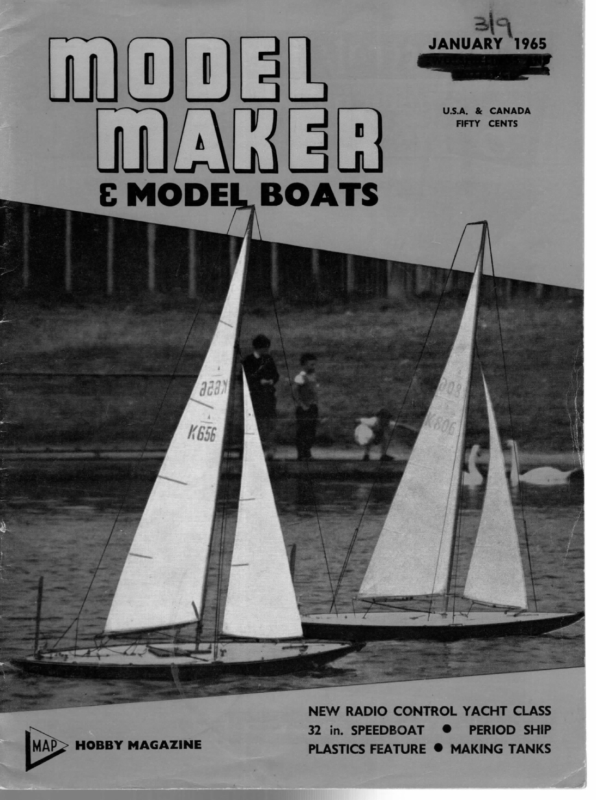

alq JANUARY 1965 U.S.A. f & FIFTY CANADA CENTS NEW RADIO CONTROL YACHT CLASS 32 in. SPEEDBOAT MAR> HOBBY MAGAZINE @ PERIOD SHIP PLASTICS FEATURE ® MAKING TANKS

In the Tideway The scene of the Santa Barbara meeting (left) with, below, “‘Rebel’? (No. 1) and ‘Sea Deuce’? approaching a windward mark, and a group of boats jockeying for a mass start. LASTIC kits are, in some way, like music. Just as all the notes are written down for you, so, in a plastic kit, all the parts are supplied ready to use. Ah, you say, but music depends on how you play it —your ability on an instrument and skill in interpretation. But don’t plastics? Your ability for deft work and your skill in assembly and, most important, painting, decide whether the finished product is just another bunch of plastic bits stuck together or a really worthwhile example of modelling technique. Critics of plastics tend to dismiss them too readily, and it seems very probable that few, if any, have ever had a go at one. People who will build a wood kit, or from published plans, sometimes tend to look down on plastics almost as much as some of the ‘Chuck a bit of hex’, etc., brigade. Yet, in principle, what is the difference between making up a scale plastic model or a scale steam locomotive? — in principle, we said. The only person who doesn’t live in a glass house in this respect is the designer who originates his own models from scratch and makes all the parts to his own design. Otherwise, building a model to someone else’s ideas is only a question of the degree of work involved. As in music, agreement is unlikely between the extremes — rhythm and blues players don’t often care for Schumann, or vice versa — but surely no-one will deny that in our case the end result is a model which, however built, has demanded care and patience and has rewarded the effort spent on it by the pleasure derived from it. Since their inception, plastic kits have made great strides and a profusion of them can now be bought. In the next few issues we propose to take a brief look at what each manufacturer is at present offering in British shops; this month’s manufacturer will be found on page 40. The “R” Class After some two years’ consultation among interested parties and consideration and deliberation in Council and elsewhere the Model Yachting Asso- ciation has, at its Annual General Meeting on Saturday, 28th November last, recognised a special Class for radio control model yacht racing. This new Class is not intended to supersede the “Q” Class, which has now progressed to International status by virtue of a resolution of the IMYRU A.G.M. of August last. It is intended to be a Class of medium size into which can be gathered the considerable number of boats, ex “M” Class, 12 6 Metres and smallish 10Raters which have already been converted to radio. Additionally, it will form a field of endeavour which model yacht designers will find fruitful and interesting. The new Rule is what is called a “Restricted”’ rule and is therefore not based on a mathematical formula. To this extent it follows the pattern set by the “M” Class Rule but care has been taken to avoid the faults of that Rule. The full Rule is set out on page 20. On the radio side the Rule provides that a certificate will not be granted unless the equipment is such that the boat can sail in company with others of its Class. This practically necessitates that the receivers shall be of the superhet type, crystal controlled. This has been deemed necessary because experince has proved that “timed circuit” racing is impracticable in sailing events. With the introduction of this Rule the MYA hopes that all owners of suitable yachts who aren’t members of affiliated clubs will now come forward and join, have their boats registered and help the sport to move forward again to new strengths —(H.E.A.)

JANUARY Santa Barbara Model Yacht Regatta The first annual Santa Barbara R/C yacht regatta was held in Santa Barbara on October 10th and 11th. There were seven yachts entered. Five of the yachts were of the Santa Barbara one-design class, one was a 6 Metre, and one was a scale model of an ocean racer. The regatta was held with 21 match races and one sail-off race between Ariel and Sea Deuce, with Sea Deuce finally winning out in a close two lap race. Both Sea Deuce, skippered by James Holmes, and Ariel, skippered by Judy Grigsby (yes, a GIRL!), sailed near flawless races, losing only one heat apiece. The course used for both days was a triangle, with a 300 ft. windward leg, a 150 ft. reach, and a 300 ft. run. On Saturday the wind started up to about 10 knots by 3 p.m. was more favourable, starting out and by 2 p.m. had freshened up knots with gusts up to 18 knots. out light, picking Sunday the wind at about 8 knots, to an honest 15 After each day’s official racing there were five and six boat races that proved to be both entertaining for the spectators and interesting for the skippers. The starting line became quite crowded at the gun. The 6 Metre yacht was a fibreglass hull built by Matt Jacobson of Burbank. It was completed just a few days before the regatta and suffered a little from rudder action which was too fast for good control. According to Matt this has been corrected and the boat is now performing well. Ichiban was a scale model of an ocean racer. The model weighed 98 lb. and was complete with an auxiliary motor, upholstered seats, life lines, and all the trimmings that go with a full sized yacht. It was a beautiful piece of workmanship. The Santa Barbara one-design yachts are being built for one design R/C model yacht racing. They are built of fibreglass to take the punishment of active racing. L.O.A. 70 in., L.W.L. 62 in., draft 13 lb., sail area 1,050 sq. in. The yacht is displacement type that moves out well despite its seemingly small sail area, allows it to sail under excellent control in in., disp. 28 of the light in light air which also heavy wind. Being our first R/C sailing regatta, we feel it was Although this is our January issue, it will be available just before Christmas. The Editor and staff would like to wish all readers a very Merry Christ- mas and all success in 1965. R/C Speed ace “Johnny” Johnson of South London club had a_ successful 1964. Here being presented with his trophies at Birmingham by Ray Meredith, who is obscuring M.P.B.A. officals King and Fish, Nelson stance adopted in background by well-known Northerner Harold Wraith. (Photo W. Barber.) HW 1965 a great success from the standpoint of the number of entrants, the quality of sailing, and the enthusiasm from both the active skippers and the spectators. We have plans for four regattas to be held in this area in the coming year. 1 2 3 Placing, Yacht, Design, & Skipper Sea Deuce S.B. one-dsgn. James Holmes Ariel cs Judy Grigsby Rebel i Tom Protheroe 4 Witch of Endor 5 6 7 Ichiban Ethlyn Halcyon s Ocean racer 6 Metre S.B. one-dsgn. Austin Munger Dwight Brooks Matt Jacobson Roger Grigsby A fine job was done by James Medsker ea Bill Everitt The death of Bill Everitt, chairman of the Victoria M.S.B.C., on November 18th at the age of 56 after a short illness, deprived the M.P.B.A. of one of its most stalwart members. Bill had achieved the highest British speeds with his hydroplanes at Amiens in September and though he was not in the best of health, his intending check-up at hospital was not thought by the party to be as serious as it subsequently proved. A short spell in hospital for major surgery and he returned home; suffering a relapse, he was taken back into hospital where he died. Bill Everitt, although mainly interested in hydroplanes, also supported other types of boats and was the donor of the trophy for the Southern Steering Championships; while not practising R/C he was an interested neutral in this. His passing leaves a gap in the ranks generally and particularly in the Victoria club, of which he was chairman for 11 years. He set an example of quiet authority blended with the art of being able to listen to all and accept all views impartially. —(J.A.K.) M.P.B.A. A.G.M. The A.G.M. of the Model Power Boat association will be held at 2 p.m. in the Memorial Hall, Farringdon Road, just a few steps from Ludgate Circus, on Saturday, January, 30th.

A. Wilcox opens his series of ‘Notes for the Novice Model Yachtsman’ with this comprehensive clarification of model yacht terminology. The series will build up to the discussion of vane gears and steering. Part 1 KNOWING THE PARTS Introduction HIS is the first of a series of articles the intention of which will be to cover, as comprehensively as possible, all aspects of vane steering as applied to steering sailing yachts and in particular model yachts. It is very evident to the author from the questions he is asked at the pondside by free-lance skippers unattached to a club and just enjoying their sailing, and the more sophisticated talk in the clubhouse, that great interest is shown in the vane gear and that it still holds mysteries to many. It will be the intention to resolve these both for the novice and the more experienced. So many of the complications of the gears used by racing skippers are just devices to meet racing regulations without being impeded, or at a disadvantage, that attention will be paid to the simpler devices which can adequately Know the Parts Before trying to sail a boat it is worth while knowing the names of the various parts and what they are for. The front end of the boat is called the bow (pronounced bough) and the back end is the stern (pronounced stern, not starn). Looking forward towards the bow the left hand side is called the PporT side while the other is the STARBOARD. The cords or wires holding the mast in place are called the standing-rigging. The main ones, from the hounds where the jib sail is attached to the foreside of the mast (about three-quarters of the way up from the deck), to the sides of the boat are called the shrouds. Their point of attachment to the sides should be behind the mast by about one sixth the width of the boat. These should be very strong to stop the mast giving in a sideways direction under wind pressure. That from the bow to the foreside of the mast, to where the jib is fixed, or to the top of the mast, is the forestay. That running from the top of the mast aft to the deck is the back stay. With vane steering this stay is invariably split about a quarter of the way up from the deck and secured on the port and starboard sides so that it clears the end of the main boom and also the vane gear. It is desirable to strut the mast above the hounds with jumper stays. A worthwhile refinement is to fit running back stays; these come from the mast at the point of attachment of the shrouds and jibsail and terminate on the side decks behind the shrouds on runners so that they can be pulled tight backwards or slacked off against the shrouds when not required, a point which will be dealt with in due course. Fig. 1 shows the points already detailed. This may seem a strange introduction to ‘Vane Gears for All’, but if you think so. then these introductory pages are just for you. The availability of the correct standing rigging and its correct use will pn the world of difference to how your boat will meet the sailing requirements of the free-lance skipper, as well as invariably being easier to construct and therefore within the ability of many more enthusiasts. It must however be said that there is much more fun and satisfaction for even the lone sailer if he has a gear capable of executing the more complicated manoeuvres. There are many controversial matters and opinions on getting the best both out of a boat and its steering gear. So far as practicable these will be given so that the reader may be led to try methods for himself, even if the author’s own opinions are not expressed. Later in the series designs will be given as well as considerations affecting design to enable and encourage the reader to experiment for himself. We must first, however, turn our attention to more mundane things. It is apparent that many do not realise that a vacht sails, or should sail, primarily on the “set” of its sails and that the steering gear is an adjunct; very necessary on some points of sailing but still an adjunct. This leads us to the first instructive section under the title of ‘Know the Parts’, in which the various parts of the hull and rigging are described. sail. The cords which hoist or hold up the sails are halliards, while those which adjust the swing of the 16

JANUARY foot or base of the sails are the sheets. These work- to a suitable screweye or a small tie. ing cOrds (ropes in Lull size) are caued tne running again liaue rigging. tue ror the sails, the Bermudian sloop rig is now so universally Used iN MOUel racung yaculs Wat tnat will be ine oly one we will consiuer, of two triangular sails. Lnis rig consists heignt aiid avove The boom is Is attacned lO ine ueck Dy Lhe Mast at a umeversal joint known as a gouseneck whicn enavies the boom lo swing clew O1 NorizONiauy the sail is and le. its aluacned to aiter the end iit. alier end ot Lne the The forward This is usually made of wood in circular, head of the sail a headboard is fitted made of light metal, bone or plastic. This helps to distribute the mast 1s Cauieu the jib and ihat benind, the main. Lhe yibsiay. ‘The head or peak otf it is secured to the mast by the jib halliard which is adjustable to enable the tension of the lutf to be varied. ‘Lhe bottom edge of the sail is called the foot. corner of it is the tack while the back corner, the clew, The tack and clew are usually attached to the oval, or rectangular cross-section. Where a radial jib-boom is used the tack is attached to the jib stay and the clew to the end of the radial jib. Both these arrangements are shown in Fig. 2. The position of the clew on the end of the boom should also be adjustable as shown. There are theoretical advantages in using a radial jib which will be described in the next section, but the practical difficulties of a really satisfactory radial jib limit their effective use to the expert modelmaker and skipper. A simple jib boom is shown in Fig. 2 where the jib boom is hooked to the jib rack on the deck from a point (preferably adjustable) near the forward end of the boom. The after edge of the sail— the leach —is slightly curved, and may have battens — small slips of wood —in pockets to hold out the curve. The threads of the weave of the cloth must run parallel to a line drawn from the head to the clew. The mainsail is attached at its head to the mast by an adjustable halliard as for the jib. The forward woou boom and, as ior the ji0, should be aujusiavie. Lne leach of the mainsail is invariably curved, at least in the top suit of sails, and has batiens fitted to hold out the curve. ‘his curve is called the roash, it improves the appearance of the sail and gives additional unmeasured sail area in the racing classes. For this reason the length and number otf the battens Lhat be.ore (in front Ol) the jib on its lorward edge—the /ujj—uis atiached to the jib boom. design OL 1965 edge of the main sail—the luff — lies permitted is given in the class rating rules. At the strain at the top of the sail and enables the sail to set better. The rating rules again specify the limiting sizes because of the way the sail areas are measured. Clearly these restrictions do not apply to boats not in a rated class and these devices should be used in these cases for appearances’ sake and the normal benefits obtained. An essential main boom fitment for really effective sailing is the kicking strap. This is an adjustable cord or wire from the base of the mast where it passes through the deck and directly below the gooseneck to the underside of the main boom making approximately a 60/30 deg. triangle. These various points are illustrated in Fig. 2. Finally a word about the sheets. These adjust the angle the boom and sail make to the axis of the boat. Since this must be varied for the course being sailed, as will be described later, they must be easily adjusted. Bowsies, which are rings of bone or plastic, sliding on jack lines—tight cords stretched along the booms — are used for this. Fig. 3 shows a typical against the mast and is attached to it either by hooks to a jack line secured down the back side of the mast, or is laced to the mast with a continuous fine cord passed round the mast and through eyelets in the luff of the sail. The author favours the latter method and finds it takes no longer to change to a rigging of a sheet. Two are required on the main boom and one or preferably two on the jib boom. The jib sheet it attached to the deck, either to a central eye, which is quite adequate for a radial jib boom, or to a horse, which is preferable for the type of boom recommended as shown in Fig. 2. The attachment of the main sheets, one of which is called the beating sheet and the other the running sheet, different suit of sails than with hooks and the jack line. The tack of the sail is secured to the mast immediately above the main boom either by hooking will be described when we deal with sail setting. ACK LINE DRESS HOOKS ON ALTERNATE SIDES JUMPER STAYS SHROUDS 17 LTT .

Te eee A NEW R/C YACHT CLASS! The “R” Class 1. GENERAL This class shall be a restricted class of medium size for use in radio control racing. Any existing yacht racing under radio control, which fits the Rule, can be granted a certificate of rating. =e 2. | be our November issue we made some fairly crusty remarks about the likelihood — or lack of likeli- hood — of ever getting an officially recognised class of radio-controlled yacht smaller than the Q. With great delight we now eat those words, for a M.Y.A. committee has been working quietly on the matter, and, on a proposition by the South-West District Committee, the “R” class came into being officially at the M.Y.A. A.G.M. at the end of November. Although “R” is the logical follow-on to “Q” it seems to us so apt for a radio class that our first thought is that this must surely be a happy augury for the class. Our second thought is that the Rule is excellent in that it embraces, with very little modification, most of the smaller radio yachts at present sailing, but gives enormous scope for future development in designs drawn up to exploit the rule. Thus any heavier Marblehead can be used, needing only its length adjusted by adding a false bow and/ or transom, and Conrads, the most popular single design for medium size R/C, and our own Wraith design, of which there are several, also fit, the lastmentioned requiring a slight increase in displacement. Quite obviously yachts designed to the rule are likely to approach its upper limits — boats to a rule usually develop into far larger and heavier craft than the rule-makers envisage; here we have maxima set and it is reasonable to expect that these will be used. A 50 in. W.L. hull, 65 in. O.A. with a 12 in. draught and beam, 30 lb. displacement and 1,000 sq. in. of sail, is not very far off a modern 10 rater, and a further thought arising from this is that we should be seeing some very fast sailing! On the other hand, a 46 in. W.L. 50.6 in. O.A., 10% in. beam, 12 in. draught, 22 pounder also carrying 1,000 sq. in. would be more portable, reasonably fast, and _ possibly handier round the buoys; the radio weight is, how- ever, a higher percentage of such a minimum size FORMULA LWL: Not to be less than 46 in. (116.8 cm.) and not more than SO in. (127 cm.). LOA: Not less that 1.1 of LWL and not more than 65 in. (165 cm.). BEAM ON LWL: Not less than 10.5 in. (26.7 cm.) and not more than 12 in. (30.5 cm.). LOADED DISPLACEMENT: Not less than 22 Ib. (9.98 kg.) and not more than 30 Ib. (13.6 kg.). MAX. DRAFTS: Not more than 12 in. (30.5 cm.). SHEER: To be a fair continuous concave curve. SAIL AREA: 50,000 LWL ( 126,995 ) LWL cm. HEIGHT OF RIG: Unrestricted. HEIGHT OF FORE-TRIANGLE: Not to exceed 80 per cent of height of rig to black band, measured from crown of deck. SPINNAKER: Luff and leach not to exceed “I” measurement; foot not to exceed (J x 2) + 4 in. (101 mm.) GENOA JIB: Hoist not to exceed “I” measurement; foot not to exceed “J’’ + 50 per cent “J”. PROHIBITIONS Multiple-hulled yachts are prohibited. 4. BALLAST Weight of lead ballast, whether inside or outside, shall not be changed during race or series of races, and any change of ballast at any other time shall require re-measurement and re-registration. Changing of batteries and/or defective radio equipment is permitted at any time provided the total displacement is not altered. 5. SCANTLINGS AND MATERIALS There are no restrictions on either scantlings or materials. 6. RIG Bermudan rigged sloop only, permitted. 7. ALTERNATIVE RIGS Alternative rigs are not allowed. Also, yachts must at all times sail with the same mast and mainboom as that carried when they were measured (except that a mast and/or mainboom of the same specification may be substituted in the event of bona- model, which may prove a handicap. We hope that this simple rule will encourage experimenters, and that time will show what sort of boat is best. Remember that such boats are not designed for the traditional beat and run; these are important, but factors such as quickness in stays are going to show a greater importance than may have been the case fide damage). in the past. 8. SatL AREA MEASUREMENT Sail area shall be measured in accordance with the LY.R.U. Rules (see diagram). The rule. is as follows; we have included for the interest of our Continental enthusiasts an approximation of the figures in the metric system. [Continued on page 25] 20

JANUARY PERIOD Introduction BY the end of the 15th century the sailing ship was entering a period of very rapid development. The fore and after (or summer) castles, which at first were mere temporary structures, became integrated with the lines of the ship. Throughout most of the 15th century the canvas carried was confined to a single large, square sail set on the mainmast as in the style of the Viking ships. But, by the close of the century the number of masts had increased 4 > ee | Parwitk’s Ship By triangular sail. This was also the birth of the age of gunpowder and the ‘big gun’ so that a number of these were carried. At first their size was such that they could be mounted in the castles but, as ordnance grew larger and heavier they were transferred to the main deck where they fired through or over the bulwarks. Even so the forecastle was still used for fighting purposes and was set high to give the bowmen an advantage while the after castle became purely residential. This last fact is particularly well illustrated by this example of the Earl of Warwick’s ship where the after castle looks rather like a marquee with its gaudily striped roof and decoration of shields. This early ship-of-war is verv colourful as one GRAHAM E. DIXEY the afterbulkhead with its arched access and steps and laying the decking. The latter needs to be drilled to take the bowsprit and, at this stage, the holes for the fore and mainmasts can also be drilled. The quarter deck, if such it can be called, is fitted between the after bulwarks and drilled to accept the mizen mast. The hull planking needs to be represented before becoming too involved in the final detail work. This may be achieved by actual laying of card or thin balsa planks over the hull blocks, edges overlapped to give the effect of clinker construction, or by scoring the planks on the hull blocks and pressing down along the upper edge of each ‘plank’. The rest is fairly straightforward detail work but the guns are worth some mention. They were usually cast, in longitudinal sections, from bronze which were bound together with iron hoops. The finished barrel was then laid on a solid wooden carriage. The guns can be modelled from dowel with paper strip binding, the ‘business end’ being drilled out for realism. The rigging is necessarily simplified but is sufficient for a model of this size to create an air of authenticity. The mainsail, if cut from a fine enough paper may be laid over the plan and traced and then painted on the front face with poster colours which will show through quite well when viewed from the rear. The foresail and mizen should be lightly lined with a pencil to represent the individual canvas strips. might expect from this flamboyant era. The main sail is fully decorated and carries the arms of Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, while a very long fork-tailed flag (gonfannon) streams from the masthead. Also in this ship we find another feature carried over from Viking practice, the carving of a figurehead, in this case a representation of a dragon’s head. The bowsprit still seems to be without a sail but continues its functions of terminating the bowlines, to the foresail also in this case, and supporting the foremast stav. It is quite likely that it also carried a grapnel as in earlier examples. Construction The construction can well follow the general lines laid down -in the preceding articles in this series. That is, a sheet keel or backbone sandwiched between solid hull blocks to form the basic hull. The main deck is then laid on top of the assembly after Colour Scheme The entire model is finished in a medium shade of varnish with the exception of the following areas: Summer castle — Roof: Alternate blue and yellow strips. Area between roof and shields: Red. Columns at corners: Gold. being scored to renresent the planking. It is as well to varnish and polish the deck before fitting as this can be difficult once the bulwarks are in place. The latter, where thev anpear, can be rebated into the deck edge: this annlies also to the sides of the forecastle structure. The latter is completed by adding Mainsail and gonfannon: As detailed on plan. Fighting top (crow’s nest): Red. R/C YACHT CLASS [Continued from page 21] Any yacht carrying equipment liable to interfere with that of other yachts in a race, shall be denied a certificate until such time as her equipment complies with this Rule. The operating frequency shall be shown on each yacht’s rating certificate. BATTEN LIMITS Battens in mainsail not to exceed four in number and shall divide the leach into approximately equal parts. Upper and lower battens not to exceed 4 in., and middle battens not to exceed 5 in. 12. APPLICATION OF RULES 13. DURATION OF RULE Except as provided for in this Rule. the General Rating Regulations of the M.Y.A. shall apply to all yachts of this Class. 10. HEADSTICKS AND HEADBOARDS Mainsail not to exceed 1 in. at base. Headsticks and headboards in foresail and spinnaker prohibited. 11. No. €arl of to three, each of which carried a sail. The additional masts were the foremast carrying a square sail and the mizen mast (also spelt mizzen or missen) which was lateen rigged, i.e., carried a fore-and-aft rigged 9. SHIPS 1965 This Rating Rule shall continue in force until such times as it is amended or terminated by the due processes of the M.Y.A. Constitution. RapIo Yachts shall carry radio equipment suitable for racing with other yachts under the M.Y.A. Rules. 25 oS

i GRAPNEL Ropes and —<¢-- Ropemoking YARNS for Scale Models Part Two SETTING UP FOR 2 YARN 3 STRAND ROPE FOR LARGER ROPES CONTINUE ROUND FOR 2nd or 3rd TIME OR MORE AS REQUIRED BEFORE TYING OFF By L. E. Zouch Fig. 3. [TS order to produce a good rope, it must be borne reached the grapnel will be seen trying to rotate and it can be given a little assistance or actually prevented, depending on the hardness of rope required. At this stage also the pear is probably bearing hard against the post which will also prevent the swivel rotating. Adjusting the positions of both pear and post allows the rope to commence forming. The ensuing part of the operation is quite rapid, by continuing to twist the strands and maintaining the pressure of the post on the pear, but moving both towards the geared end at a rate which can soon be estimated with a little experience. A rope of con- in mind that all the strands and yarns must be of even tension. If this is not so, flaws will develop, spoiling the work. It does not necessarily follow that the entire length must be scrapped, as short lengths are often required, but it is obviously better to guard against this happening at the outset. The underlying principle, then, in setting up, is to wind the yarn on to the appropriate hooks in one length in such an manner that they can be tensioned by pulling on the weight cord, in the same way as the load tensions the rope in a multisheave tackle. Another point to observe is the avoidance of knots in the length of rope. Any joins made in the yarns should be positioned at either of the ends and the yarn cut about half an inch from the knot. Unduly sistent hardness should result. Due to the length of the machine, a second operator is useful to turn the handle whilst the pear and post are controlled by the “Ropemaker”. When the pear approaches the geared end, the post can be removed and its duty taken over by the ropemaker’s index finger, if it appears necessary, until the pear falls clear of strands. Continue to turn the strands until the maximum length of rope is obtained without undue strain, and remove the rope from the machine in the following long ends can tangle and cause trouble, particularly at the swivel, by winding into it and preventing it from rotating freely. Because the Terylene yarn is rather fine it is not always apparent and a lot of trouble can be experienced before the cause is discovered. When we left the machine, it was supported at a convenient height, and with most of its parts in position. We can now proceed to set up the yarns and lay up a length of rope. The easiest to lay up is two yarns, three strands, so, taking this manner. Now all ropes are liable to unlay if the strands are not secured, so we must guard against this eventuality. Synthetic ropes are particularly prone to this because of the springy nature of the fibres. With the finger and thumb of the left hand, grasp the rope as close to the end of the twisted strands as possible and cut each strand off its hook with scissors. Then without releasing the strands or the tension (the weight is still supported by the rope), tie a knot in the end. We can now move to the other end. As at this stage there is still some residual tension in the strands, we should be careful not to release the rope too quickly, or it may tangle. It is best to work along the length hand over hand, allowing the surplus twist to unwind as we go. The first thing to do as an ex- ample, we proceed as follows. Fig. 3 will simplify the description. The yarn as purchased is on one of the usual wooden reels, so we tie the free end to the first hook, that is, the one at the rear of the machine. Then holding the reel in the finger and thumb of the left hand so that it can revolve, walk to the other end and pass the yarn round one of the hooks on the grapnel. Come back to the geared end and pass the yarn round the second or uppermost hook, then back to and round the second grapnel hook, then round the third or front hook at the geared end and back to the third grapnel hook. Pass the reel underneath the yarns and come back to the first geared hook and tie off. Cut off as mentioned previously and rotate the spindles to give a few twists to the yarns. Adjust the tension by pulling the weight cord a few times, and insert the pear at the swivel end with the strands lying in their respective grooves. Place the post on the beam so that it passes vertically between the second and third strands approximately two inches to the right of the pear, and continue to twist the yarns. Nothing spectacular will occur, apart from a shortening of the distance to the swivel, until sufficient turns have been given to the strands. When this point is at the grapnel end is to secure the strands with the finger and thumb of the left hand, and place the loop of the weight cord over its hook. The rope may now be cut from the grapnel and the strands again secured with a knot, in the same way as before. Although this may sound quite a long process, in fact it is not. One complete length of rope can be laid up in less than five minutes once the principle is mastered, and the product is superior to the usual run of rigging cord. To cut off shorter lengths from the stock length, tie two knots about 3 in. apart at the required point and cut between them. An alternative method, which [Continued at foot of opposite page] 36