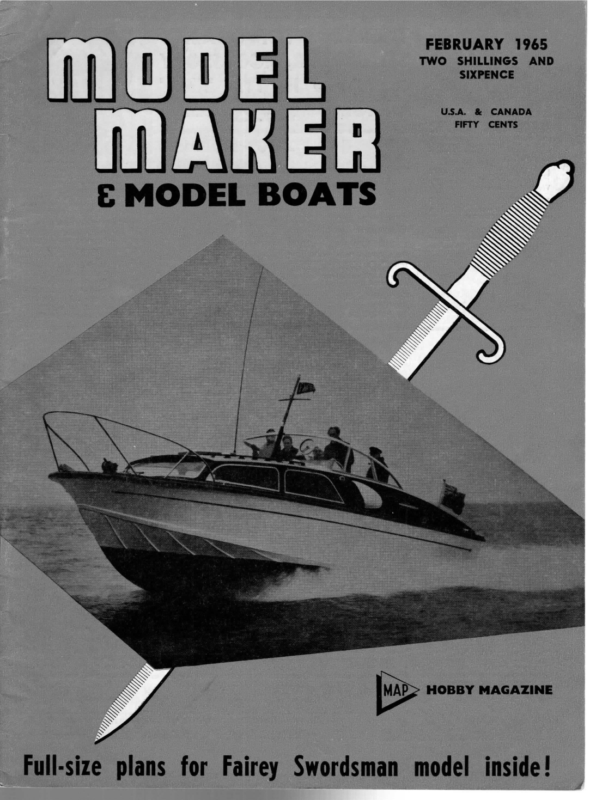

| | FEBRUARY 1965 | TWO SHILLINGS AND SIXPENCE | 1 US.A. & CANADA E MODEL BOATS HOBBY MAGAZINE Full-size plans for Fairey Swordsman model inside!

AOR DAREDEVIL, sss An intriguing A RESTRICTED class can only exist by experiment and the development of new ideas. The development of the high aspect ratio rig and its adoption in the Marblehead class has led to a gradual change from a narrow, easily driven hull form to a more powerful one. However, there is a trend towards even heavier and bulkier boats that I do not think is desirable. There is an attitude in nearly all Marblehead design that completely ignores planing performance and concentrates on windward work. The Marblehead should be the most exciting of the three classes because it has the lowest maximum displacement speed and should therefore be the first to get up and plane. Why then is this side of Marblehead performance not exploited? I think it is due to the fear of losing windward performance and because the lack of forward overhang makes design for planing difficult. I know that comparison with full size dinghies is wholly unjustified, but nevertheless I think it may serve as a guide. Until about six years ago the National twelve foot restricted class was made up of boats not designed specifically for really good plan- | M) R Stall ing. However, since then this planing performance has become the major consideration. The National twelves achieved their aim of improving planing performance by reducing the canoe body depth (or rocker) and making the unimportant bow sections flatter. Again the fear of losing windward performance loomed up as it now does in the Marblehead class, but they got over their difficulties by making the bow waterlines above water level fine in order to slice cleanly through the waves; also they im- proved the stability by flaring out the sides, but without increasing the L.W.L. beam too much. If these factors are realigned in model terms this means: (A) (B) (C) (D) Reducing the rocker. Flattening the bow sections. Keeping the waterlines fine, but remembering the tendency to dive under downwind. ne the stability without increasing the . eam. I should now like to give account of my experience of experiments concerning these points. My sister’s boat Brandy Snap is a narrow ‘U’ sectioned nineteen pounder with a comparatively small rocker and was excellent in running and marginal planing conditions because of the two factors (A) and (B). But she was hopeless to windward, because the combination of her normal type keel and her narrow hull made her too unstable. However, I applied point (D) and Oe aS ee ee L aU \ al J ae a = pyara WSs Pte r=] —| axe | = er beac ea ie Witn=GiE | : \ – iicwer CISFLACEMENT weil at hy seen sue fone 20618 Nocumnie si sisvock arcs 7 hee

FEBRUARY changed her keel for a plate and bulb type which was 30 per cent more powerful than the original. This keel made a fantastic improvement in her windward performance and also gave her the ability to plane on the reach, which was the deciding factor in last season’s National Championship. Following the success of this experiment I tried this bulb keel idea on my own M, Lazy Devil. Lazy Devil has a moderate beam and “V” sections; it displaces 20% lb. and has a fine entry, but enough flare to prevent diving under on the run. Her original keel was quite normal and the combination produced a very good all round performance. However, this happy state was ruined by the bulb. The windward performance, which was very good before, was improved, but the downwind and reaching suffered because it was too stable. This may sound nonsense, but to get the right amount of dynamic lift from a “V”” sectioned hull it must heel to show a flat surface to the water. When running, this is detrimental, and when reaching, the boat must be heeled within a small critical angle range in order for it to plane. This means that on gusty days this range may only be encountered for short periods, probably not long enough to make the boat plane. These experiments led to the conclusion that a “U” section must be sought, if good marginal planing is to be achieved, because a “U” sectioned boat can be at any angle of heel and still show a useful planing 1965 surface to the water. A round section also has the advantage of having less wetted surface than a “V” section of similar displacement. This is, of course, very important in light weather. Comparison between Lazy Devil and Brandysnap also shows that reducing the rocker is an important factor in improving marginal planing, because it straightens out the lines and produces a shallower wave form. Daredevil is an attempt to combine the superb marginal planing characteristics of Brandysnap with the excellent windward characteristics of Lazy Devil. The midsection has the same displacement and wetted surface as Lazy Devil’s but has a shallower depth. It was found that the rocker could be reduced by 17 per cent to just over 23 in. without exceeding the 10 in. beam and still retain a fair, well-rounded section. The bow sections carry through this round below the waterline and straighten out into a largish flare above it. This produces waterlines fine enough to slice through waves, and yet sections which are powerful enough to prevent submerging downwind. I am satisfied that the bulb keel idea has potential and therefore it will be the key to the windward and reaching performance of Daredevil. Although the ballast is only 13.6 lb. it has the same righting moment as a normal keel carrying 17 lb. Looking at the keel sections they may seem rather ambitious, but I have made two similar keels and know that it can be done. I used 4 in. Tufnol sheet with two cheeks of the same material glued to either side. Sandwiched between them were the keel bolts in 3 in. long slots in the main sheet. This is quite satisfactory if “Araldite” is used for the gluing and if pins are driven through the plate to prevent the bolts pulling straight out. The keel can then be shaped to the desired section using a spokeshave and plane. However, this system using bolts can be dispensed with if you do not want the keel detachable, and the 4 in. sheet can simply be built into the hull. I decided that in order to get the frontal area of the circular bulb as small as possible, I must not just cast two half bulbs, and bolt them either side of the plate, so I cast the plate itself. bulb over the bottom of the The mould takes a bit of setting up, but it is worth it in the end. I have shown two top suits on the plan, one for lighter weather (HT) with a 75 in. hoist and a working top suit (WT) for moderate conditions. Some on Daredevil but I myself prefer the 75 in. rig because it can often be carried to advantage when the taller rigs have to be changed. I think that it is essential to fit Marbleheads with a well cambered foredeck, so that any water taken aboard is thrown off immediately. However, this poses problems if the curve is taken the whole length of the boat, because the rig has to be lifted to maintain the important kicking strap power. This means that the height of the centre of effort is being unnecessarily elevated. The answer is to make the after part of the deck concave and to step the mast in this part, so that it reduces the heeling moment of the rig and therefore increases the boat’s stability. I have shown the foresails as they would be set on a forestay fitting with a kicking strap, because I feel that the adjustment of the twist in the jib should always be made with precision. I hope that this design has provided some food for thought and that it will help to guide the way for further development in this field. wraz / [W147 5° HOIST 5925″ +] may prefer a slightly taller light weather top suit and I am sure that this rig could easily be carried oo EES 61

Sf os A — rs Notes for the Novice Ce. WI ANGLE OF JIB —~ ANGLE OF MAIN” va CLOSE PORT MAIN ANGLE OF VANE ~ BEAT Model Yachtsman ~ Sail Setting FREE S72 REACH By A. Wilcock WE saw in the introduction and rigging for plain sailing the various parts of the standing and running rigging. We can now turn to sail setting and at least start some sailing. Before we do, however, let us just go back a moment and see that our standing rigging — on which much of the performance of our boat depends — is set up correctly. This is done because if you are going to get your boat to sail well you must get into the habit of continually doing this. Racing skippers do it during a race, not only just before the start. Start by seeing that the shrouds are reasonably taut and hold the mast upright, relative to the hull, in a sideways direction. This is best done with the hull on a stand, either on a table if your boat is small or on the floor if it is one of the larger classes and sizes. If you tighten the shrouds too much you will bend or distort the mast between the hounds and the deck and this is to be avoided as much as having them so that the mast can wave about. Now adjust the backstay so that the mast leans backwards slightly, say 1 in. for each 2 ft. of mast above the deck; this is called the rake. Finally tighten the [ —VACK LINE < DRESS HOOKS OW f ~~ ALTERNATE SIDES forestay until it just holds the mast from being pushed backwards. Now take the boat off its stand and lay it on its side —look down the mast from its top and you should see a fairly straight mast — if not look round to see which part of the standing rigging needs adjusting to make it so. It may be that the forestay only comes up to the hounds and that the backstay is bending the top of the mast backwards from this point, particularly if the mast is light in construction. This can be corrected by fitting jumper stays which is their real purpose. It is easy to see that a main sail with a straight luff can never be properly “set” on a mast bending, as distinct from leaning backwards. Fig. 4 shows the details of the jib sail. First notice the way of the cloth in the cut. It is impor- tant that the leach is parallel to the selvedge of the material. Do not think that the seam on the leach will give adequate strength on crosscut material because it will not. The roach on the jib is quite small, about 4 in. per foot run. Now look at the jib stay and note this is independent of the jib halyard or uphaul and has its own adjustment bowsie —a flat one is most suitable. This separate adjustment enables the lift of the jib boom to be controlled. By putting this bowsie near the bottom it will not be confused with the bowsie near the top used for the setting of the luff of the jib which is the next point to note. SEAM OF Look now to the clew of the sail and see the simple means that can be adopted to set the foot of the sail. Arrange things so that the clew can be hauled back practically to the end of the boom, since the jib must be set so that the sail just clears the mast in swinging from side to side and a long un- used end of the boom does not allow this. Part of the metal top to an old fountain pen or lipstick holder will be found useful material to fashion a neat strong end to the boom. The horse, where one is fitted, should allow a boom movement of no more than 122 deg. each side of the centre line of the boat. This is about the angle for a close beat (see later) and enables the clew to be held down fairly tight, i.e., the horse aids the tension on the jib stay. Summing up the fitting of the jib we have (1) The way or weave of the sailcloth must be parallel to the free edge (leach); (2) The jib stay must be 70

FEBRUARY 1965 fashionable varnished nylon, varnished Terylene, and P.V.C. on Terylene materials, cut the luff straight. If you are using cloth an inward curve enables the sail to be trimmed flatter for heavy weather while an outward curve gives a baggy sail, more suitable for light weather: Clearly the straight cut is a compromise if you are only going to afford one top suit. The degree of curve could be say & in. per 2 ft. run really tight; (3) The jib boom is hooked to the jib rack on the deck so that its end just clears the mast in swinging from port to starboard. The use of the other hook positions will be discussed in sail trimming. Before finally leaving the jib it is appropriate to say a few words about radial jibs as mentioned earlier. Looking at the jib arrangement just discussed, two. disadvantageous features should be mentioned. The first is that to hold the clew of the sail down the boom is used as a lever with the jib hook as fulcrum and the jib stay pulling on one side of it. Thus, when the jib is set for beating at, say, an angle of 15 deg. to the axis of the boat, the luff of the sail moves slightly to windward and the plane of the sails is no longer on the axis of the boat but slightly to windward at the bow, i.e., the hull is pushed slightly to leeward for a. given sail setting relative to the wind. Theoretically then the boat will not sail quite as close to the wind as if the luff of of luff. The luff is secured to the mast either by dress hooks to a jack line attached to the mast or lacing through eyelets (now obtainable with pressing pliers, quite cheaply from Woolworths). Both methods are illustrated in Fig. 4. The luff is hauled tight with a halyard and bowsie from the head and secured to the mast about the hounds. enough to It should be only tight prevent bagging down the mast, not stretched. This will of course vary slightly according to the strength of the wind. The attachment of the beating and running sheets to the deck will vary according to the type of steer- the jib is anchored to the centre line of the boat, which it is with the radial jib. Experience shows that this is only marginal. The other disadvantage is that, because the tack and clew of the sail are secured to the two ends of a continuous boom, the “flow” or bagginess of the sail is final for all angles of sail setting unless one is constantly adjusting the clew. It is generally advantageous to have little flow in the beating or close hauled condition and quite a bit of flow in the reaching running courses (see later for explanation of courses) and this the radial jib to experiment with automatically gives. If you want’ a radial jib these are the design points to watch. (1) See that the post on which the radial jib is mounted points towards the hounds, ie., it is not parallel to the jib stay but is at a slightly steeper angle, and is strong. Since it may be desirable to move it nearer the mast when using the smallest a mast slide is a useful suit of sails a base like ing gear used and will be described when we come to steering gears. In the meantime it is sufficient to say that where a horse is used it should be no longer than necessary to give a-12 deg. movement of the boom either side of the centre line of the boat. A kicking strap is essential for good sail trimming and it must be strong. Stainless steel wire or a cycle spoke with a good bottle screw is ideal. In its tightest adjustment it should hold the boom from lifting to the same extent as the beating sheet pulled home although this tightness is used more on the run when the boom is let well out and the kicking strap prevents the boom lifting and the sail bellying out forward of the mast. In the beating adjustment the kicking strap is eased slightly from this adjustment allowing the tension to come on the beating sheet, but more of that anon. We can now turn to sail setting and trimming. As was mentioned earlier the course a boat sails should be primarily determined by the set of the sails. Fig. 5 can be called a sail setting compass and is worthwhile copying and carrying with you until practice has committed it to memory. By placing it on the ground or holding it in. the hand with the. wind arrow on it pointing in the direction in which the wind is blowing one can see the sail settings required for any practical course from the point at which one is standing. Let us however explain the chart in more detail. The single arrow shows the assumed direction of the wind, while between the two circles are a series of yacht hulls pointing in different directions relative to the wind. Superimposed on these are curved solid lines representing the jib and mainsail with their angles relative to. the axis of the boat, for the boat can sail in the direction it is pointing relative to the wind, as shown by the wind arrow. On courses on which a spinnaker can be set this is shown dotted for both boom and sail. Note how on the broad reach and free reach it is a flat spinnaker almost like a genoa: jib set inside the jib, while on the running courses a balloon spinnaker outside (in front of) the jib is carried. Note also how the spinnaker boom is always a little more forward than the line of the main boom extended forward. The short straight solid line near the stern of the boat shows vane angles and will be referred to later in discussing vane steering. Round the outside of the double circle are given the names of various courses, those on the right hand side being port tacks or foundation. (2) That it is as tall as the sail plan will allow so that the stresses caused by the wind pressure on the sail transmitted at the clew will not cause binding. This:is the greatest difficulty to over- come in obtaining a satisfactory radial jib. (3) The kicking strap which controls the lift of the boom must be of metal throughout and the bottle screw strong, as the tension in this link in a strong wind can be very considerable. (4) The distance of the radial jib post behind the jib stay is a matter of opinion but about 1 in. per 10 in. of the foot of the sail is a good starting point. Now let us turn to the main sail, also depicted in Fig. 4. First note that the cloth runs from the head or peak of the sail to the clew, not parallel to the mast. The latter is the commonest fault noticed with novice made sails, and their baggy leaches can be seen right across the pond. The tack of the sail is hooked immediately over the gooseneck or tied to it. The ‘clew is secured to the end of the boom in an adjustable manner similar to that of the jib. The roach of the mainsail is usually limited by the rating rule giving a limit to the length of battens permitted. Practical considerations limit the roach to 40 to 45 per cent of the length of batten permitted. Where, as a novice, you are not limited by rating rules, again 1 in. per 2 ft. run gives a nice appearance, and you may wish to experiment with fully battened sails. Whether the luff of the sail is cut precisely straight or has a slightly outward or inward bow or curve depends on both the sail material and what you want the sail for’ With the currently [Continued on. page 73] 71

Advanced Trimarans Erick J. Manners comments on a recent article by E. J. Charlton HAVE just read the article on ‘Trimarans’ that was published a few weeks ago in the December tion 26 with hydrowing altitude very slightly lower than 21, but with angled hydrofoil blade set under as shown on lee hydrowing, at nearer 42 beam for uncrewed models and definitely to embody the auxiliary reserve sponson concept 43 as always embodied full size. These binary formulae numbers apply to the illustrated 1954 to 1960 series of conducted experiments shown in my 1961 Trimaran Volume 2, page 34. For further instance of effectiveness one might quote from Multihull News, No. 36, by the Hydrofoil and Multihull Society (founded 1954). Accounts from entirely independent users here quote such proof as highly experienced yachtsmen saying that the Trifoils and Triforms open up a new era in yachting. Speeds like 20 m.p.h. before tuning, in a 20 ft. Trifoil. H. & M.S. sailors believe they have touched over 30 m.p.h. and still know how to effect further J. improvement. The open, day-sailing Trifoil is stabilized by almost non-buoyant wetted-wing hydrofoils and these are certainly not considered by the designer as at all suitable for stabilizing uncrewed models. However, the model enthusiast need not despair, be- some simple concept of native double outrigger canoe stabilized with ordinary buoyant floats. Such a model would sail quite well even if it were not made very accurately and everything about it would 23 ft. wide Ocean Cruising Triforms, stabilized by hydro-wings, as in Ted’s illustrated model, can get within a spectacular few miles short of wind speed. For instance, 10 knots in 14 knot winds, which is twice the speed of an orthodox traditional yacht in similar circumstances. Likewise even in six to seven issue of the Model Maker. This article by E. Charlton calls for some comment by me, although unfortunately this can be in no way comprehensive in less than a booklet, simply because scientifically the subject of advanced trimarans is so vast. By this is meant that any model maker could follow be understandable to all. By comparison the Tricruiser dynamic hydrofoil stabilized trimaran illus- trated in Ted Charlton’s treatise would rapidly overtake to flash past an example of the primitive outrigger. If say the speed difference were double, most users, both full size and model size, would be more than satisfied. Not so the author, nor myself. I have seen some of Mr. Charlton’s know he is a perfectionist. in the advanced worker, miniature scale. beautiful work and This is how it should be equally at full size or His trimaran, which he has named Tricat, is stabilized with my patent hydrowings, but without the full complement of intrinsic relationships that I advocate for full size use. This asymmetrically winged model has sailed faster than his quite exceptionally fast model catamaran. However, I would not unreservedly go so far as to agree with his Suggestion that it may go on to reach phenomenal speeds, except in a spasmodic and impractical way for all round use, at least at full size. In the past I have made full-size hydrofoil craft lift the hull out under sail with spectacular results, but due to the fickleness of wind and wave the experience is shortlived. Suitable con- ditions seldom exist at full size, yet they might well do so in model form. Notwithstanding, I can assure readers the following. cause even one of the relatively huge 45 ft. long by feet high Atlantic waves the 45 ft. laden Triform touches the fantastic sailing speed of 20 knots in only 25 knot winds, under ordinary working sails. This Owner says the stability and gentle motion of this boat is unbelievable. It is understandable that these criteria are called revolutionary. This American writes that his brother’s comparable size pedigree ordinary boat only does 8 knots in much stronger winds and rolls badly. Both these .reactions are typical of conventional yachts. Before closing this partial reply I must correct one error; the 1961 book entitled ‘Trimarans’ (Incorporat- ing Hydrofoil Craft), almost entirely written by me, has absolutely nothing to do with the Amateur Yachting Society mentioned, to which it is incorrect- ly attributed by your writer. Likewise this mistake applies to such as the reference to the 45 plus different hydrofoil, float and outrigger arm experiments I carried out at full size. It is true that from its outset, for seven years, often advocating real research, { attended every committee meeting of the A.Y.R.S. but throughout that time I never came across any actual active research carried out directly by the Society. Much of my research, together with the publication of other books was, however, To revert again to the crude native outrigger model example mentioned in my last but one paragraph, nothing you do to this makes much difference. Like all slow boats it is relatively unsensitive. On the other hand the ‘Triform’, as the advanced trimarans like Tricat are called, are sensitive in the extreme. This is not so in an impractical way, but dynamically they must follow a much more exacting mathematical relationship. conducted with the active and gratefully acknowledged assistance of members of the Hydrofoil and Multihull Society. This research organisation, established over a decade ago, invites the assistance of model engineers in serious experimentation and hopes that Ted Charlton and his stimulating work will continue to lead the way. Where else can one pioneer in a world-leading scale? Let’s hope that the Model Maker is the first to publish plans for the flying wing Triform in model form. I have already supplied over a thousand com- Alas, I feel there are a number of things in Ted’s fine model that are still not in model scale relationship to the full size Trifoils and Triforms that have taken me over 10 years of full time work to develop. For example, I should like modelists to try configura- plete sets of constructional plans for such full size asymmetric stabilized craft to every quarter of the globe, so the barriers are broken and the way Open to further progress. 84