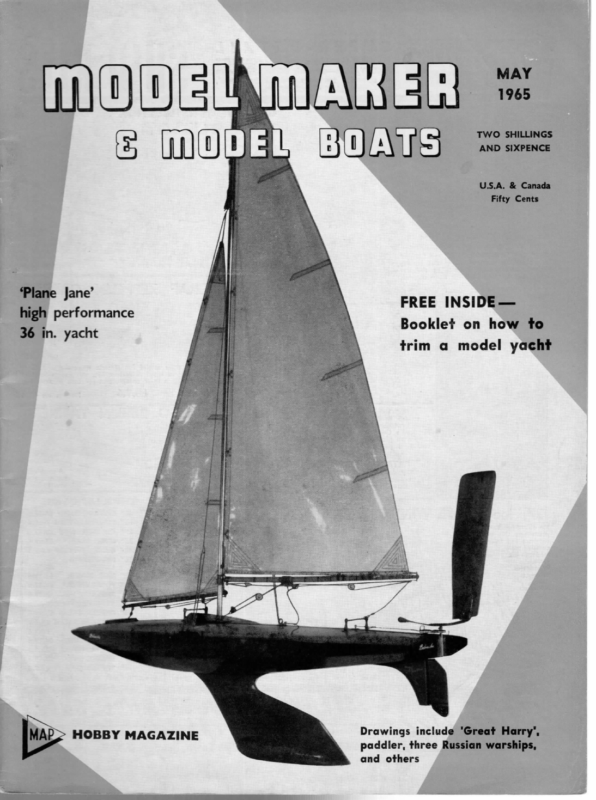

- PLANE JANE AN UNUSUAL 36 in. YACHT, SIMPLE TO BUILD AND CAPABLE OF OUT-STANDING PERFORMANCE

- PART 1 By F. G. DRAPER A CO-AXIAL VANE GEAR Easily made with hand tools, this gear answers many of the problems of vanes. By ROGER STOLLERY

- Notes for the Novice Model Yachtsman A. Wilcock this month discusses how the vane actually works and wind effects

1 Sie E FB OA Se 0)0 U.S.A. & Canada Fifty Cents ‘Plane Jane’ high performance 36 in. yacht FREE INSIDE — Booklet on how to trim a model yacht HOBBY MAGAZINE Drawings include ‘Great Harry’, paddler, three Russian warships, and others a et a

CUE WOR IMIANKIE(R} PLANE JANE AN UNUSUAL 36 in. YACHT, SIMPLE TO BUILD AND CAPABLE OF OUTSTANDING PERFORMANCE PART | By F. G. DRAPER A FEW years ago a series of “one-of-a-kind” races was held in America to ascertain the fastest type of sailing boat. Without going inio details, the results indicated that the light-displacement scows fared extremely well— much better than had been expected. More recently in France a similar series of races was organised by the French yachting magazine Nautism, and once again length for length this type of boat proved to be very successful, in spite of conditions which did not allow the scows to demonstrate their excellent planing performance. It has been stated that an American A class scow can beat a 12 metre round a three legged course. One of the finest examples of this type of boat is the British Fireball. The production prototype of the class had less than two hours’ sailing before being entered in a one-of-a-kind series of races in 1962. Even in light weather and without a spinnaker she was first home. This boat was also the first centreboarder of 13 ft. 3 in. waterline length to be allocated a Portsmouth Harbour rating of 86. The success of the “quick planing” type of craft is not difficult to understand as it has certain advantages of the more normal displacement boat. The most important of these is its ability to transfer part of its weight from the relatively dense water to a lighter element, air. This results in a reduction in wetted area, but more important, the boat’s speed is not limited to the same extent by the sailing length rule. In other words it has a tendency to fly over the water instead of having to set up wave patterns as it ploughs through it. Existing model yacht classes and racing rules do not encourage the designer to produce purely planing types of craft. Recently, however, there has been a proposal to instigate a new class (the Orbit) which would be less inhibitive to this type of boat. Plane Jane is an experimental model designed to adapt the modern planing dinghy to model form. There are certain special problems for the model designer to overcome on this task, the major one being the old problem of resolving light weight, high power with stability—for, above all, it is essential that the boat should revel in being driven hard, one might say “over driven”. in. Hull balance is an additional most effective for all points of sailing and left alone. Ideally, this ballast should keep the hull as upright as possible, yet be easily lifted. This is best achieved by placing the lead low down and combining this with an extremely light hull and minimum weight aloft. It follows therefore that much care should be given to the design of the stabilising appendages as they will be travelling through the water at all times and producing turbulence. The model skipper cannot haul up his fin or centreboard on the run like the full size dinghy sailors. Boat designers, long ago, discovered that you “cannot have your cake and eat it” and the scow is not at its best in very disturbed water; like a racehorse it prefers going to be good. It fares best on draughty inland lakes—but if caught out by a freak gust of wind the resulting gyrations can look extremely embarrassing. I have found that this sort of thing is more likely to occur before planing speed has been reached, as once in full cry the boat presses on regardless. Fig. 1 shows the bows of two hard chine boats. The hull form illustrated in A represents the more normal chine arrangement, whilst B is the chine set up found in Fireball and Plane Jane, In Fig. 2, the Hull form and positioning of sail must work together in lifting the total weight when sufficient drive comes firstly because any bad balance is accentuated if a relatively short beamy boat is heeled to a large angle—especially one requiring a flat and wide run aft. Furthermore, by its nature, this type of hull is subjected to rapid changes of attitude in the longitudinal plane. The model designer cannot count on an agile crew to either induce or balance out changes of attitude. His ballast must be placed where it is problem, 188

MAY 1965 two hulls are heeled to the deck in the same strength of wind (it is assumed that boat A being less stiff “initially” will heel to a greater angle than B). If we now compare the underwater sections it can be seen that the angles formed at point X will move to windward, In the case of yacht B, X now becomes a cutwater and in fact, resembles the form of A when upright. This is a great advantage as it helps to prevent slamming when on the wind, this when the yacht is most likely to be in the heeled attitude. On the other hand, when running more or less upright, the shaded portion presents a flat lifting sur- \ é x fe i in face, just what is required. Turning to yacht A, almost the reverse is found to be the case. Preliminary experiments were made on a small 18 in. model using the Fireball chine arrangement which I felt has everything to recommend it, Even in this small scale the boat exhibited planing qualities both with and without a spinnaker. Thus encouraged, a larger 36 in. model was built, resulting in the boat to be described. The primary aim throughout was to concentrate on reaching and off the wind performance; nevertheless, beating to windward proved better than I had been led to expect. Final trimming was carried out with what amounted to a second top suit of sails, anticipating the sort of conditions in which the boat would give its best performance. Trials showed that the ballast could be reduced as the boat was very stiff and further improvement was achieved by moving the lead fore and aft until an optimum position was found, giving good windward performance without detracting from the tendency to lift quickly on the run. It was found that the placing of the C.B. is fairly critical in this respect. The extra weight of a larger and slightly heavier rig, bringing the C.G. a Mu) PLANE JANE fee hm pees fraction for’d, almost killed the boat’s “downhill” performance. This once again underlines the advisa- bility of keeping as faithfully as possible to the original design, at least for a start; improvements can be made after experience in handling. The hull’s rather unusual chine arrangement com- bined with a slight reverse sheer gives the boat a distinctive appearance without complicating the construction. In fact this boat is suitable for a first effort, being simple, light in weight, and small enough to be made on the kitchen table. There are no complicated joints, but as with all boat building, time, patience and a liking for working accurately with nice woods is needed. The primary reason for accuracy is because the hull of a yacht should be symmetrical and any lopsidedness will cause un- wanted steering effects, particularly when it heels. While on this subject, half the battle is won by ensuring that the building board (our stocks) and preliminary marking out are absolutely true. One is often asked “how much did it cost’? The materials will cost roughly £5, though it could eee 189 WINNNNINNNINUHSEY4I)

ot KIER) (31 probably be done sources of supply. for less, depending on one’s Before describing the method of construction used on the prototype model one must point out that an experienced builder may use alternative methods and materials, but the beginner is advised to stick closely to the original scantlings, also he is reminded that water has a habit of getting into everything that is not thoroughly waterproofed. To overcome this problem the use of a good full-size yacht varnish helps and of course any metals used should be nonrusting. Brass is the most common. First of all study the drawing until all is clear in the mind, then prepare a list of scantlings (material required) at least for the canoe body. Other items can be bought as required throughout the construction, but it is as well to have enough materials at hand to finish the hull. Most of these can be obtained at a wood yard or model aircraft supply shop, but quite a few useful pieces of wood can be found in odd places. For example a cedar cigar box makes excellent material for the outer transom, rudder, and deck breakwater. Bits of brass can be found as well. Recently I was admiring the “heel fitting’ on a friend’s mast, whereupon he told me that he found it in the Christmas pudding—it was a tiny thimble. A visit to a supplier of fishing tackle is useful. Brass wire paternosters incorporate a little universal joint, which can be used for the jib tack, as well as brass wire for hooks, etc. Brass curtain rail from Woolworths can be cut and filed to make shroud plates, jib rack and the mast step, and so it goes on. Construction Before starting the building, parts of the boat will have to be traced out. These will include the formers, transom, deck beams, fin, skeg, and rudder. Saving weight is the keynote in construction. The builder should beware the temptation to add bits here and there—they all add up! On the original model even pins were removed after the Aerolite 306 glue had set. The hull is built upside down on an accurately planed piece of 40 in. x 4 in. x 1 in. pine or like wood, It is an advantage if the wood yard planes this timber for you. A centre line is marked lengthways on both sides of this board. These centre lines are important for lining up the model, in fact they are probably the most important lines of all as they represent the centre of the boat. The position of each section including the for’d and aft transoms are then marked across the board and squared right round to the underside. Six wood blocks 4 in. x 1 in. sq. are then prepared and a centre line marked round the middle of each. These blocks will support the moulds and aft transom. An extra triangular sectioned block holds the apron bow or for’d transom in position. The positions of the sections are marked out on the board in the following manner, Put the first mark 23 in. from the end; this represents the loca- tion of the forward face of the inner aft transom. Measure 68 in. from this line and put in the next station. The spacing of the next three sections is 7 in. followed by 4 in. and 34 in.; this last line represents the aft face of the forward transom. A second line iz in. forward of this should also be drawn. Later in the construction the transoms will be faced with 3% in. or 3 in. cedar or mahogany. Note that the moulds numbered 2, 3, and 4 are erected with their aft faces on the transverse lines, while numbers 5, 6 and the aft transom have their forward faces on the lines. To facilitate this the blocks have to be arranged accordingly—see drawing. be forward transom block is lined up to its line also. To enable the boat to be removed from the board later on, the blocks are first located with a single screw. The board is then turned over and two screws are put in each block from the underside. The temporary screws are then removed, leaving the blocks held by the two screws from below. The formers and transoms are now carefully traced on to 7; in. sheet spruce using carbon paper, remembering that Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 are in two portions. It is best to butt two pieces of wood to- gether along the line of the join, hold temporarily, and trace off using this join as the datum line. Allowance must be made for thickness of the planking jj; in. and remember the moulds are extended to meet the building board. After tracing off, the moulds and floors are taken apart, numbered and cut out separately, including the notches. Once again a centre line should be drawn on both sides of the moulds to aid lining up on the board. Care will be needed in cutting out the forward transom as its rake makes the angles of the notches rather acute. It is best to treat the erection of this member as a fitting job, constantly checking the angles. The forward and aft transoms will of course be made without the joins. The mould floors and transoms are now tacked against their blocks; the two portions of the mould and floors will have to be rejoined temporarily. Panel pins are used in this process. The stringers, 4 in. x 4 in, spruce, and the chines and inwales, 4 in. x 2 in. spruce, are then prepared and bent across the formers. The notches will have to be eased out at the forward and aft station with a small file so that they take the curve fairly. [Continued at foot of opposite page] Two-level deck and simple fittings are shown in this close-up of the mid-deck area. Rigging and fitting details will be dealt with in part two of the building — to appear next mon 190

mE: + B.A. SWEET Up a I 1 /00 /50 ‘OYER S2FEET Model JADED i Yacht warships wie by D. A. MacDONALD These notes formed part of Seees lines a series of articles published in ‘Model Maker’ in 1955- 1957 and are reprinted by popular demand. HE amount of time and effort involved in tuning up a yacht for maximum performance varies very considerably. Some boats reach their peak performance after a few hours of sailing time—others are still not giving of their best even after a season’s racing. The time taken depends mainly on two factors. One is the amount of care taken on the design and construction—obviously a boat which has faults will take longer to sort out than one which is free of vices. The efficiency of sails and gear enter into this to a large extent. The second important factor is the way in which the tuning-up process is carried out. If this is done systematically and logically it will obviously produce better results in a given time than will haphazard sailing and random guesswork. The final stages of tuningup will involve the skipper as much as the yacht, because however perfect a craft may be, the skipper must know its behaviour well enough to be sure exactly what effects will result from any change of trim under any kind of sailing conditions. = Es 305 MISSILE LAUNCHER LENGTH \ 130 FEET SPEED 3S KNOTS APPROX. 199 VNU HL Tuning 1965 MAY

MAY 1965 tional design, propulsion, and steerage, and is powered by a Kelvin type “T.8” eight- cylinder diesel rated at 240 h.p. A speed of 10 knots can be maintained. Pilot can accommodate 10 seated pilots in her deck saloon aft of the wheelhouse, while another saloon is available below decks if required. A small galley and crew’s room is also placed below. All ac- the Inspector is on the deck, below and forward of the wheelhouse position. She is operated by a crew of three, and cost in the region of £32,000 to build. Power is by a Gardner 230 b.h.p. diesel engine at 1,150 r.p.m., giving the cutter a good working speed of just on 10 knots. Full engine control is available from the wheelhouse where the skipper has a good all-round view. As a matter of record, Victor Allcard came into service at the beginning of March, from when she could be safely depicted in any scene modelled of Thames activity. Her colours are: very dark blue hull with yellow-chrome painted trim line and name, and green boot-topping. Superstructure is white with varnished oak sliding doors and a yellow-buff funnel. Later commodation is plastic lined, with plastic tiles for the floor covering. Central heating is also fitted. A big feature of the wheelhouse design is the incorporation of an angled anti-reflection front. This is unique at the time of introduction for Thames harbour craft. Full engine control from the bridge is fitted. Metal non? decks are another feature of this smart small craft. Colours for the new Pilot are black hull with red boot-topping and name in yellow-chrome paint. Decks are black. Superstructure is buff with oak doors, Mast and handrails are white. are black, the mast is white. Fittings are ack, “Pilot” This column has in the past featured the old steam cutter Pilot, and the later motor launch cutter Pilot II. Arriving on the pilotage service scene in March of this year was the latest cutter to bear the long-used name of Pilot for London River basing. Pilot entered service for the River Pilots’ Committee at Gravesend just a few days after having arrived from the builder’s yard. Numbered as 1280 by the builders, Pilot was specially constructed for Thames use by James W. Cook & Co. at their Wivenhoe yard, Essex. Unlike others of her type to be seen in service of recent years, this vessel is of conven- CO-AXIAL VANE GEAR [continued from page 206] The wire loop W is pivoted in a hole in the aft end of plate B and is attached at its other end to a spring. The object of this gadget is to make the carriage definite in its movement from one tack to the tached by a similar disc with a & in.- Whitworth threaded rod glued through its centre. © The ‘simplicity of the construction of this gear makes it ideal for home building. For a few shillings one can make a gear as good as those that cost other. In a lull immediately following a gust or in a bad header, there is a tendency for the boat to go into irons and prevent the gear working effectively. However, this device helps the gear to bear away smoothly in these conditions. The arrangement of the tacking lines from the main horse slider to the carriage is shown in the photographs. The hub of the vane arm K is a block of Tufnol with a grub screw inserted for friction on to brass tube J; the counter- balance arm and the feather arm are’ glued into it with Araldite. The feather arm consists of a length of 4 in. diameter aluminium*rod, bent and‘ glued round a‘lin. diameter Tufnol disc. The feather is at- pounds. The most difficult thing in making the vane gear is to find the brass bevel gears. Model shops specialising in an engineering field are the most likely to be helpful. Meccano gears are good to fall back on, if nothing else suitable can be found. Meccano contrate and pinion gears were used successfully on the forerunner of this particular gear. It would probably be necessary to alter the dimensions of the carriage to fit the various sizes of gear chosen, but ey, the construction could remain the same. Tt is hoped that this article will arouse interest in moving carriage vane gear development, and also be of use ‘to those who wish to make an efficient’ gear at reasonable cost and labour. “901 | | eee 1 Ue TS

SSS » K are nN er M S : inal cpa c D F E eo aoe 4 ° B ES sprig —<¢ a = G Ny N — . rudder tube SECTION CT | yy NN i ‘ 7 \\ \\\ is POT 7 we N AY c \ z = — — SECTION zz _ i = i ‘ / Wg ete > = / \\ \ | a l key. to hatching j \ -— brass , E SSeS ° = ‘ T formica/ tufnol \ , / to main horse i aluminium DSSS SSS \\KKE ) aa Z See ee YT , to spring by roger stottery z PLAN SECTION xx E&F, A, tormica top bearing plate of carriage. B, formica bottom plate: C&D, tufnol pillars forming the basic structure formica. bearing plates H,1/8″ aluminium rod L, for centre forward carriage pillar: V8″ diameter’ shaft for gear N: duminium. centre Gdjuster tor. indicator’ unlocked bevel G, a small section of tufnol 3/16″ diameter brass rudder shaft: N,M,O, 3/4″ diameter R, 16 swg- wire carriage : 1, gear N* arm V, carriage lock: wire loop used S, to transfer carriage load 3/16″ inside diameter 24 tooth brass bevel gears: for self-centering line W, J, tube P, between A&B: to formica deck bearing plate brass tube with’ plug. to centering spring xX: K, vane arm 1/8″ inside diameter bruss spacer tube, Q,1/8″ diameter 1/8°diameter brass carriage centre marker on formica scale T. U, angle to give positive action to carriage on either one R c&D Z components . = vr U ° oe ey LZ VANE GEAR ‘ 504T 3 MPH. — > BROAD REACH wr ye ee ai Caer, TRUE WIND WIND 9 M.PH. 10 MPH. . VENEER OAT TRUE WIND 10 MPH. SKETCHES FOR MERCHANTMAN CONSTRUCTION Hi a“ 2MPH. CLOSE courses. Strictly speaking boat speeds should be in knots, that is nautical m.p.h., but it is certain you will appreciate working in m.p.h. with which the majority of us are much more familar. One thing to observe particularly about the direction of all the apparent winds is that they appear to come from closer to the direction the boat is sailing than the true wind you feel when trimming the boat from a stationary position at the pond side. An allowance based on experience must be made for this. No doubt you will wish to draw for yourself more apparent winds in other directions and with different 10N_OF 2 => 142 M.PH. CLOSE ing to the probable speeds on the various courses, 13 m.p.h. on a close beat, 2 m.p.h. on a close reach, and 3 m.p.h. on the broad reach and running IST > APPAR js ° a length proportional to its strength. Fig. 20 illustrates the apparent winds for a number of starboard courses, The wind has been taken as Z eo aid “N “ ~ DECKS OF NO.2 BRISTOL BOARD ALL CUT FROM SINGLE STRIP ANDO CURVED FRONTS ACCURATELY MATCHED BEFORE CONSTRUCTION OF DECKHOUSES NO.5 BB. VERTICAL VENEER STRIPS BULWARKS NO.2 8.8. STUCK CONSTRUCTION OF SUPERSTRUCTURE TO DECK. JOINTS FILLED WITH SUCCESSIVE COATS OF HUMBROL RUBBED DOWN BETWEEN EACH COAT NQ2 BRISTOL BOARD g WO.3 BRISTOL BOARD REST— 2 THICKNESSES VENEER NO.2. B.B. BULWARKS SLOTTED INTO RECESSED DECKS COVERIN SUPERSTRUCTURE r LOVERING excerr wo’s 42.03 ALL NO.3 8.8. — PAPER © OR TRANSPARENT PLASTIC. “BRIDGE FRONT COMPLETED WIT WITH PAPER STRIPS STUCK TO GLASS FRONT AND PAPER SIDES VENEER Ss il QR, winoow cur porogh SIDE BEFORE FIXING CRANE coal 2 THICKNESSES NO.3 8.8. 213 ATT a)