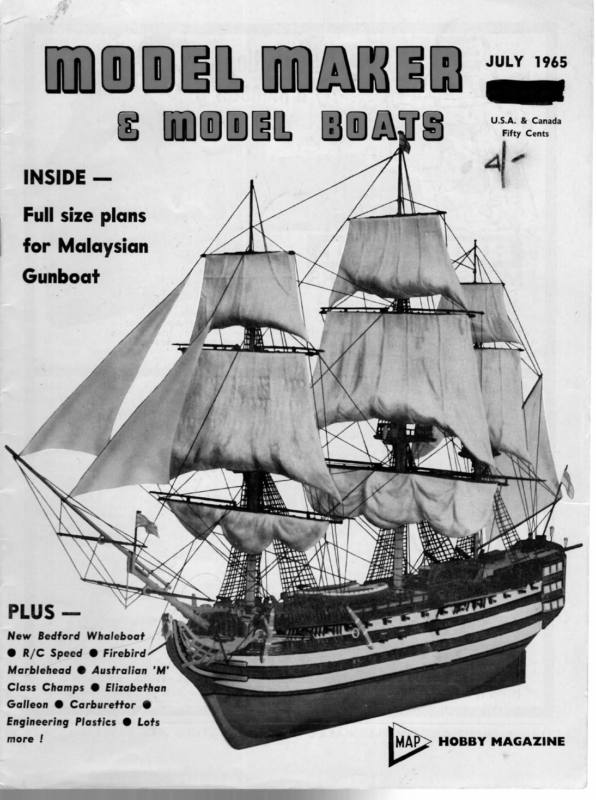

OUEL BOATS U.S.A. & Canada Fifty Cents a“ INSIDE — Full size plans for Malaysian Gunboat PLUS — New Bedford Whaleboat / @ R/C Speed @ Firebird Marblehead @ Australian ‘M’ Class Champs @ Elizabethan Galleon @ Carburettor @ Engineering Plastics @ Lots more ! MAP> HOBBY MAGAZINE

nn ie was my original intention to design a 36 in. Restricted Class boat as part of a series of hard chine craft, but I have since for many reasons changed my mind. Owing to their large sail area and many suits of sails 36s are as expensive as the average Marblehead, just as difficult to build, and very much more difficult to sail—which is probably the reason for their rapid decline in recent years. I decided, therefore, to design a very easily constructed Marblehead, even simpler to build than Flamenco my last design, which should be able to hold her own in a very competitive class. To fulfil the basic requirement of being easily constructed she has been given only ne chine which has, to some extent, governed the choice of stern. A transom would have been ugly, and with such a flat run would have adversely affected the balance. The canoe stern was therefore the logical conclusion. To have a successful chine boat the displacement must be fairly light, or otherwise the lines will be too coarse. This is particularly so in the case of the single chine vessel, but does not affect the multichined vessel to quite the same extent. The reason for this will become apparent if one compares these two types of section with that of the round bilge vessel. It will be seen that to get the same displacement the body depth and beam of the chine boat will have to be greater than that of the round bilge vessel. Fortunately, the Marblehead rule does produce a light displacement boat and so is eminently suitable for hard chine construction. The displacement of Firebird is only 15.5 lb. which, for a Marblehead, is very light indeed. Displacement is a factor which must be placed on the detrimental side of the performance scale when assessing speed potential. The heavier the boat, the more power it requires to drive it at a given speed, all other things of course being equal. One of these factors that must be equal is stability. If one can therefore produce a boat of very light displacement with the same stability as a very much heavier boat it should, in theory, be faster. One example of this is the catamaran, which is light, stable and very fast. Unfortunately, the principles employed in the catamaran cannot be used here. There are, however, other means of obtaining more stability for a given weight and to see how this has been done in Firebird let us first take a look at the various factors that make up stability. Stability can be divided conveniently into three main parts, each of which can be altered separately but which work together to form the stability of the boat. The first of these is usually referred to as natural stability because it is entirely dependent on the hull form of the vessel. As can be seen in the diagram, the centre of buoyancy, normally on the centre line when the vessel is upright, moves to leeward when the vessel heels. The centre of buoyancy is the position through which the force of buoyancy, which supports the boat, can be assumed to work vertically upwards. In the diagram this line of force is represented by an arrow drawn vertically upwards through B cutting the centre line at a point M which is known as the metacentre. The second factor affecting stability is the position of the centre of gravity which can be assumed as being the position through which the weight of the vessel works vertically downwards. In the diagram it can be seen that the centre of gravity is a constant factor and so remains on the centre line of the vessel when she heels. This force can, therefore, be represented as a line of force working vertically downwards through the centre of gravity. Firekind a brand new hard chine Marblehead by D. M. Jd. Hollom We now have what is known as a righting couple. There is the force of buoyancy working vertically upwards through B and the force of gravity working vertically downwards through G. The tendency is for the vessel to move upright again at which time the two forces will be working in equal and opposite directions along the centre line of the vessel. To return to the heeled state of the vessel. It will be seen that if the centre of gravity is moved lower down in the boat the righting arm GG will be increased in length and a longer righting arm will be achieved and the vessel will be more stable. The same effect can be obtained by moving the centre of buoyancy further to leeward, thereby producing a higher metacentre and a longer righting arm. There- fore, the higher the metacentre and the lower the centre of gravity the more stable the boat will be for a given weight. This brings us to the third factor, the actual weight of the vessel. The power of the righting arm is dependent on the weight exerted at one end of it and, as already mentioned, on the length of the arm. This power is expressed as a multiple of these two factors known as a moment. If we want to increase the righting moment and thereby the stability of the vessel, we can either increase the length as already explained or increase the weight. It also follows that if we increase the length of the righting arm and decrease the weight we can produce a moment of the same magnitude as that of a heavier boat, which we assume to possess the optimum stability for that particular class. This is in effect what has been done in Firebird. 282

JULY The first factor, a large movement of the centre of buoyancy to leeward, was achieved by using a moderate beam, a shallow section and a thin plate fin. It must be remembered, that on heeling, the fin moves to windward of the boat and any buoyancy contained therein will be tending to pull the centre of buoyancy to windward which will detract from the final stabi- lity of the boat. It will be appreciated that the plate fin will contain only a fraction of the buoyancy of a conventional fin and will not, therefore, adversely affect the stability. It must be mentioned at this stage that the extra buoyancy in the fin of a conventional boat is more than offset by the extra lead ballast it is able to support. Because of certain other factors, such as the distribution of lead ballast, the position of the fin in relation to the hull, and the need (in some cases) to keep the hull lines fine, it is invariably resorted to in varying degrees. However, in the case of Firebird the aim was to produce a very light boat and as much buoyancy as possible is contained in the hull. The second factor, that of obtaining a low centre of gravity, has been achieved by placing the lead ballast as low as possible in the boat. A lead bulb is the most efficient method of doing this, but produces problems of its own. The ideal position for the fin is with its toe approximately at the mid-length of the boat. This is quite feasible in the case of the conventional fin, as the lead is carried in the fin’s leading edge, which keeps the centre of gravity under the longitudinal centre of buoyancy. In the case of the plate fin, however, it becomes increasingly difficult to place the toe of the fin in its correct position. The centre of gravity of the lead bulb must come under the centre of buoyancy and this, in itself, means that the toe of the fin will be well forward in the boat. This can, however, be overcome to some extent by contracting the lead in its longitudinal direction. In 1965 Firebird the bulb is constructed of lead in the fore- part and of wood in its afterpart. This has the effect of moving the centre of gravity of the bulb further forward which enables the bulb to be moved further aft, while preserving a streamlined shape. Admittedly, the bulb is larger in section than it need have been, but I believe this to be a small price to pay for good handling characteristics. This now brings us to the third factor of stability, that of weight. A large righting arm has _ been achieved by fully exploiting the first two factors which has enabled a very light displacement to be used while retaining the stability of the heavier boats. I am confident that she will have enough power to hold her top suit as long as most and, because of her light displacement, I hope she will prove faster. Turning to the hull, it will be seen that the greatest body depth has been placed further forward than is usual which gives a long flat run and a fine entry. The forward sections are well flared and the bow at deck level is quite full, all of which will help to prevent her for doing a nose dive and should produce some exciting planing performances. The rudder is placed as far aft as possible and the vane will be mounted forward of the rudder post. As a final word, I would like to point out that for simplicity of construction the lead bulb is cast in two parts, each of which is a true half circle when viewed in section. These are then bolted together on each side of the fin so that, when completed, the bulb is in fact (owing to the 8 in. thickness of the fin) wider than it is deep. I mention this as in some designs of this type the bulb is designed to be a true circle after fitting to the fin. I would be very glad to hear from anyone who builds Firebird as it is only from reports on performance that a design can be improved. FULL SIZE COPIES OF THE PLAN REPRODUCED AT A REDUCED SCALE BELOW ARE AVAILABLE FROM MODEL MAKER PLANS SERVICE, 38 CLARENDON ROAD, WATFORD, HERTS, AS PLAN MM/828, PRICE 5/6d. PLUS 6d. POST AND PACKING. FIREBIRD D.M.J. Hollom COPYRIGHT MODEL MAKER 28, CLARENDON RD, OF PLANS SERVICE WATFORD, HERTS.

JULY by a Government surplus electric motor on accumulators supplying 20 v. at 5 amps. R/C gear was R.E.P. Sextone. Second in the same event was K. Townend whose 38% in. Thorneycroft M.T.B. to MM plans (MM337, price 7/6d.) is powered by an E.D. Super Fury. Radio gear when used is S/C Modelectric. First place man C. Senior ran an electric powered 49 in. M.T.B. For use in R/C events, his boat, too, is fitted with radio—in this case R.E.P. A. Armitage’s Cervia (MMS567) model took first in concours, the tug electrically driven through a modified Kako 4 motor by 3 x 2 v. Government surplus accumulators. This model employs motorised switch gear giving forward and astern. E. Emmerson’s all metal steam launch (2nd concours) measures 37 in. x 8 in. and is all the work of the owner. C. Ledwidge (3rd) ran an electric model of the cargo boat Caledonian Monarch which is 42 in. long with a beam of 7 in. 765 14th Annual Regatta, Poole, May 8th-9th This meeting, from which our heading photo comes—Culver Woolley’s Gannet 15 powered Bertram 32 scale model White Tornado—has a reputation for being the trial ground for the season’s new models and ideas in general—this year was no ex- ception and out of the 34 competitors taking part, many of the newer boats were of the “flattie” or “semi flat” varieties. However, strong wind put paid to these models’ chances and scoring was left largely to the more conventional hulls. RACE RESULTS: Event 1: Ist R. M. Mogg; 2nd P. Nottingham; 3rd H. A. Brierley. Event 2: Ist C. Johnson; 2nd W. D. Taylor; 3rd H. A. Brierley. Event 3 (Bravery Challenge Cup): Ist I. J. Wood; 2nd L. R. Wood; 3rd N. Portlock. Event 4 (Freemans Challenge Cup): Ist E. R. Millward; 2nd G. Woolley: 3rd N. Portlock. Event 5 (Amazon Cup): Ist C. Johnson; 2nd L. Wood. THE FIRST AUSTRALIAN MARBLEHEAD CHAMPIONSHIPS Report and photos —G. Middleton (Sec. A.M.Y.A] if bees first Australian Marblehead Open Championship was sailed on Easter Saturday, April 17th, here in Adelaide on the Patawolonga River. It was to be a two day event, but due to damage sustained by three of the eight boats entered, the lousy weather, and the dropping out of one contestant due to health and the heavy going, the O.0.D. Mrs. Mavis Smith decided that as we had completed one round on the Saturday, we would call it a day. Of the eight boats entered, five were from South Australia and three from Victoria. The day started off with very heavy rain, and as soon as there was a break, racing started at 10.30 a.m. in a 36 m.p.h. breeze gusting to 46 m.p.h., mainly from the West but at times from W.S.W. Later in the day it became less gusty but remained a steady 35 m.p.h. from the West. The course was over a 380 yards stretch of the river which is 100 ft. wide at its narrowest part. The slight bend in the course made things quite interesting for those who like to live dangerously, and at times frustrating for the more timid type. The Victorians found things a bit strange at first as their mode of sailing is slightly different from the MAIN ROAD Left, ‘Playtime’, a hard chine private design from Melbourne, leads ‘Flamenco’, ‘Poogee’, and ‘Nautilus’ on the run back. *‘Poogee’ and ‘Nautilus’ are both after ‘Festive’ (Daniels) while ‘Flamenco’ is a Hollom design published MM April °’64. Final scores were ‘Jaqualine’ 24, ‘Playtime’ 23, ‘Mischief’ 20, ‘Nautilus’ 13, ‘Sirena’ 12, ‘Flamenco’ 11, and ‘Poogee’ 2 Mh

general run of things owing to the nature of their home waters. However, they were not far behind when we stopped for lunch after sailing half the round when scores were: S. Australia J. Smith R. Carter G. Middleton P. Lesty 7 6 5 Victoria J. Dailey N. Romeril I. Romeril Neil and Ian Romeril. 8 uf When we resumed after lunch the weather had cleared and the rest of the day only saw a couple of light showers. Sailing was more pleasant and as we settled down the pressure was on. Some very fine sailing by Neil and Ian Romeril and John Smith. I saw two very close finishes—a boat’s length between Ian Romeril (Victoria) and G. Middleton (S.A.) and two boats’ lengths between Neil and Ian Romeril (Vic.). A glance at the score sheet and the accompanying snaps will give some indication as to the conditions and the pressure of the day’s sailing. In the last heat of the day, P. Lesty lost his steering on the outward board and was unable to return. As the scores showed one point between first and second, Mrs. Smith O.0.D. asked for a sail-off for first and second place between John Smith and Neil Romeril with John the winner. Now this may not sound very significant to the experienced competitors, but Neil is only 16 years of age and just come into the Marblehead class. He previously sailed 36 in. R for a short time. stirring the members to come over and join the fun. So successful was he that they sent their Commodore to keep an eye on things. It is only a coincidence that Keith who is their Commodore is also the father of At the presentation of the prizes, the President of the Model Ship and Power Boat Club of South Australia, Mr. Fred Ames, expressed the pleasure of all the South Australian members at having three boats from Victoria of the Albert Park M.Y.C., and Jim Dailey, who was the prime mover over there, in The President then presented John Smith with the Bournville Challenge Trophy which was sent to the Model Ship and Power Boat Club of South Australia as a goodwill gesture to further the interest in model yachting in Australia. We decided to put it up for an Australian Marblehead Open Championship for all craft in this class belonging to a club which comes under the jurisdiction of the I.M.Y.R.U. Also in the first prize went a suit of sails made to the winner’s specifications and donated by Rolly Tasker, a leading Australian yachtsman and sail-maker. John being well fitted out with sails, and an exmember of the Bournville M.Y.C., continued to uphold the goodwill gesture of Bournville by handing the order for the suit of sails to Neil Romeril. Fred Ames then presented Neil with his Trophy which | have no doubt by now will have been shown around the Club to the envy of those who didn’t or couldn’t come over. In parting the Commodore of the Albert Park M.Y.C., Mr. Keith Romeril, expressed the gratitude of the Victorians for the South Australian hospitality, the fine sailing, and good fellowship they had enjoyed with us. He apologised for bringing the bad weather with them (standing joke about Melbourne’s weather) and informed John Smith he would have to take a good look at the Trophy as he would only have it for 12 months after that he would have to come to Melbourne to see it. So ended one of the most pleasant weekends ! have spent, in spite of the rain. Top left shows ‘Mischief’, Romeril (APMYC) Ian releasing in the windward berth. John Smith (MSPBC) at his side lets go ‘Jaqua- line Kornig’, a Littleiohn ‘Restive’ design. chined ‘Mischief’ is a ‘Play of development Time’. Top right, |. to r-., P. Middleton (scorer), I. Romeril, K. Romeril and J. Dailey—boat in foreground won the event. Left ‘Mischief’ left and ‘Jaqualine K’ right. 292

mae mAtaa gl de Lassel type gear has, as mentioned, among its other features a simultaneous adjustment of port and starboard tacks, and Fig. 23 shows this in detail. Note that with this gear the carriage is locked in the fore and aft position when the gear is “broken”. We can now look at the question of balance in the broken condition and for this Fig. 24 will be useful. This figure shows the ideal condition in a single line form where the weight or mass of the feather is the same as that of its counterweight and they have both moved through an equal angle of say 35 deg. Their leverages are therefore equal and the gear is NOTES FOR THE NOVICE MODEL YACHTSMAN—A. Wilcock continues his notes and moves on to guying balanced, in that there is no unbalance of gravitational forces to give the rudder a bias. The forces or moments are each equal to the radial distance to the centre of gravity of the mass times cosine 35 times the mass. Since we have made the masses the same and the radii then all is well. Now look at Fig. 22c which is the configuration applying to the Lassel gear in the “broken” condition. Here if the masses of the feather and counterweight are the same and say the radius of the feather is 3 in., then for balance in the fixed condition the counterweight would also be on a radius of 3 in. This radius is however made up of two parts, say 1% in. each, which come into play when the gear is broken. The moments of the feather angle of movement of the counterweight which in the case of the Lassel type gear helps towards balance. The other device is the Guying elastic. This is terminated so that the pull in the non-guying setting goes over the dead centre and therefore helps to hold the pin against the end of the slot. This must not be overdone or the gear will fail to flop over when the boat is tacked. With the guy setting arm in the vertical (neutral) position the force applied to the motion tends to hold the gear to whichever tack it is on. and counterweight are then mass of feather times 3 (inches) times cosine 35 while that of the counterweight is mass of counterweight (the same as the feather) times (13 times cosine 35, plus 13). Cosine 35 is .813 so that we see the feather moment is 2.43M while that of the counterweight is 2.72M giving a considerable bias in favour of the counterweight which in turn will give weather helm, i.e., if the gear is balanced in the fixed condition it will tend to steer it off the wind in the broken condition. To those not so mathematically minded, Fig. 22c is drawn to scale —or you can draw it out to a larger scale—in which it can be seen that the line of action of the counterweight is farther from the central pintle and will therefore exert the greater force. This inability to balance the Lassel type gear in the two conditions, without adjusting it, is undoubtedly its greatest fault. Looking at Fig. 22c again you will see an arrow pointing at the face of the feather. This is the face of the feather that will “feel” the wind if the boat. when sailing, tends to fall off the wind. Wind on this side of the feather gives LEE helm to steer the boat up into the wind and we say it gives this positively because the pressure on the pin and slot movement to the counterweight is locking them harder together. If the wind strikes the other side of the feather due to the boat or wind heading, then the force on the feather will try to unlock the pin in the slot. The power of the gear to give weather helm is therefore not so great. This characteristic is minimised by two devices in the design. The first is shown in Fig. 25 which shows how the pin and slot motion is proportioned so that the tendency to unlock under pressure is minimised. This requires a slightly greater IDEAL BUT IMPRACTICABLE ARRANGEMENT ‘ eX ST wz! ’ \ ate A ‘ = 5 (ae | GOOD PRACTICAL ARRANGEMENT \ b omean / / 7 Now to Explain Guying If the guy setting arm is pushed over to a horizontal position, say on the starboard side, the elastic will pull the feather and counterweight arms on to the starboard side. If the counterweight is manually moved over to the port side (the feather will automatically follow due to the pin and slot linkage) it will be noticed that the elastic is not now taken over a dead centre and on releasing the hold on the counterweight both arms spring back to the starboard side. To sail the boat now with this setting of the guy it will be found that the performance on the port tack is quite normal because the arms are held over to the starboard side as required. When the boat on coming to the bank is turned, new forces affect the gear; firstly the heel of the boat on the new tack gives a gravitational force to the counterweight to swing it to the port side, aided by the weight of the feather which in turn also has the wind on it now to blow it over to the port side, and opposing these movements is the guying elastic trying to spring both 296

JULY 1965 arms back to starboard as was described a little earlier. What in fact happens depends on the strength (1) of the elastic, (2) that of the wind, which heels the boat, and the angle to the wind to which the boat is turned. If the elastic is very strong it will hold the feather and counterweight arms against the other forces and the wind on the feather will cause so much helm to be given that the boat will quickly spin round back on to the port tack—hardly a guy at all, but one that must be classed as a short guy. If the elastic is weak then the gravitational forces created by the heel of the boat and the wind pressure on the feather will be such that the boat will sail to the other side of the pond on the starboard tack unless there is a complete lull in the wind when all the heel comes off the boat and this boat motion coupled with the elastic tension will swing the arms over to starboard and the next little breeze IF X 1S MADE % Y THE ANGLE AT THE JOINT ENABLES THE FEATHER. TO just through the eye of the wind. It will then be found that by turning it further you will execute a longer guy, and that movement of the arm nearer to the vertical will continue to lengthen the guy. Finally it must be emphasised that long guys largely depend will on a be varied by the position of the guy setting arm between the horizontal and vertical positions. The ideal adjustment is such that with the arm horizontal a shortish guy is executed when the boat is only turned An attractive presentation wallet of minia- VANE QUERY DEAR SIR, I am a reluctant critic; even so, I think the following comments on Mr. Stollery’s Vane Gear in the May Model Maker will be helpful to Mr. Stollery and readers, and if he will reply helpful to myself as well. The writer saw experiments on the lines of Mr. Stollery’s gear by two or three members of Danson M.Y.C. in about 1957 and I am therefore particularly interested to see the form come to light again, but unfortunately with the same defects that led to the abandonment of the (1957) experiments, that is unless Mr. Stollery has something up his sleeve he hasn’t disclosed. The gear is in fact a form of moving carriage gear since one moves a carriage with sun and planet wheels in an unusual formation to obtain the tack motion. His little force diagrams are very interesting as far as they go but apply essentially to the vertical or stationary forces. One must consider applied side forces, which with a moving carriage gear are the tacking sheets, centring line/s and guys. Mr. Stollery unfortunately did not mention guys or their point of attachment, but I would presume they are the same arms to which the tack sheets are hooked. It LL rvooer rosr CARRIAGE = =. ==— “1p BOTTOM PLATE i RUDDER POST TOP BEARING DEITIES LESS ISS 95 DECK 5S) lull in the wind or sailing into a calmer patch. The latter can very often be operated with great consistency. Guying has been gone into in some detail here because this same form of guy is common also to the next two gears to be described. that the restoring power of the elastic guy can also ture chrome-vanadium spanners in the hardto-get B.A, sizes is presented to the writers of letters published in the Readers Write feature. The Editor is not bound to be in agreement with any view expressed. [To be continued] was found in the 1957 experiments that these forces caused (1) the rudder post top bearing (deck level) and (2) carriage to rudder post bearings, to be too binding and requiring more power than was available come them from the (when vane sailing). to over- It was theorised at the time that the solution lay in a bottom carriage bearing of the type one gets in a pedal of a pushbike as illustrated. This is both a thrust and side bearing and could therefore completely relieve the rudder post of the weight of the carriage and take the side pull of the tacking sheets with- out them being transferred to the rudder post. Unfortunately the construction of such a bearing was beyond the experimenters, and stainless steel bearing balls, which are essential in such an application, were well nigh impossible to come by. I am vary chary of passing these comments on high esteem as Mr. one held in such Stollery but I am sure he will be willing to pass comment and let out his secrets. Finally I must say how intrigued I was with his wire loop toggle action to the carriage, a device I am certainly going to try on my moving carriage gears. Sidcup. A. WItcock, VANE ANSWER DEAR SIk, I am glad that the article on the vane gear in the May Model Maker has produced some comment from the experts. However, it is only fair that Mr. Wilcock should see the vane gear he is criticising in action, before he picks out its faults, rather than comparing what he thinks it is with unsuccessful experiments. The vane gear illustrated in the May issue works extremely well, and the binding forces which Mr. Wilcock imagines are not apparent. Before considering any friction diagrams, it is necesary to establish under ~ what conditions friction (which is inherent in all vane gear) is likely to prevent the gear working properly. In light weather the frictional forces are LARGE in CONSIDERABLE PRESSURE THE MOVEMENT UNLOCKING REQUIRED. quickly bring the boat round on to the port tack. This would be a long guy. A little thought will show Readers Write EXERT WITHOUT OVER THE RANGE OF FEATHER ANGLES comparison with those forces which can be supplied by the vane feather. Thus the tendency to bind increases as the wind strength de- 297 MM creases. Mr. Wilcock must agree that vane gears are not in the habit of binding in heavy weather, unless, as in the case he mentions, there is something radically wrong with the adjustment of the attachment forces (tacking, guying’ and centring lines). In these higher wind strengths even large frictional forces are NEGLIGIBLE compared to those forces which the feather is able to supply. Therefore consideration of friction at the light weather end of the scale is of the only real importance. In these conditions the boat can be consi- dered upright and attachment forces small. Hence the diagrams in _ the article. The guying lines about which Mr. Wilcock enquires used to be attached to the same points as for the tacking lines, until recently, when they were replaced by a more easily adjustable system. The wire toggle became more useful than it appeared at first. It was realised that it was being used in the same way as the elastic band between the links, on a conventional linkage vane gear. Such an elastic band is used for guying as well as for making the arms positive in action. The wire loop on the gear shown in the May issue is now used for guying, by making its point of attachment adjustable across the deck, on a bowsie or similar device. As it is moved across the boat a point is reached where the carriage does not stay on that tack. It is not clear from the photograph (intended to show the layout of the tacking lines) that the latter are simply crossed from the carriage and led through the ends of the horse to a simple slider. In this way the horse takes most of the mainsheet pull, and provides a more gentle tension than would be the case if the lines were led directly from the mainboom to the carriage. It is hoped that Mr. Wilcock will accept the fact that this gear is of a very simple construction, and that to introduce complex bearings is really not in the programme. I am quite certain that such a bearing as suggested would have negligible effect on the performance of the gear, in view of what I have said on the subject of friction earlier in this letter. Woking. R. STOLLERY,

JULY brass, % in. long, drill and tap 2 B.A., and slow running screw carrier from ;’; in. diameter brass, 35 in. long, drilled and tapped 6 B.A. The main body can now be assembled. Pass the +é in. diameter piece over the 4 in. piece, insert the jet carrier and slow running screw carrier, press on the flange piece, and silver solder all together. When cool, quench off and, gripping the main body in the four-jaw chuck, bore out body 4} in. diameter x +; in. deep. While at this setting, also drill or bore the 4 in. diameter hole at the “back” of the body recess. 4} Aluminium is suitable for the barrel, which is in. diameter x § in. long with a 4 in. diameter peg 8 in. long a sliding fit in the drilled or bored hole in the body. Slip the barrel into the body and clamp; chuck by gripping the flange, centre, and bore through .4 in. Remove from chuck and while still clamped run a 6 B.A. tapping drill through into the aluminium plug. Use #s in. hex. stock for the jets; turn ;; in., screw 2 B.A., centre and drill & in. deep with No. 77 drill. Reverse in chuck and drill No. 46 to meet 77 drill hole, then counter-drill No. 38 4 in. deep and tap 5 B.A. For the needles chuck a 3 in. length of 5 B.A. steel screwed rod, drill ;; in. 4 in. deep. Turn 3m in. 1365 diameter head, drill and tap 5 B.A., apply a straight knurl. The needles are from ;’; in. drill rod or mild steel with case-hardened tips and are soft soldered in place, as are the heads. A piece of ;; in. rod turned and threaded 6 B.A. forms the slow running screw. Stop springs for the needles can be made from-the springy brass from 43 v. flat batteries. It should be necessary, if assembly is correct, to file a small groove to clear the second jet. The only critical point about the whole unit is that the banjo with the two extensions must go to the second jet. Banjo and throttle arm construction need no special comment. For tuning an O. and R. engine fitted with this throttle, the best procedure has been found to be to open No. | jet about 4 turn and to screw in the slow running stop to about the 3 throttle position. Pull the engine over once, choked, and it should start on the second pull. Adjust the jet until the engine is running smoothly, and then slack off the slow running screw until the engine is running as slowly as_ possible. Owing to the very stiff reed valve on this particular engine very slow running is not really possible. With the engine at a safe tick-over speed No. 2 jet is opened until full throttle can be given. COMMERCIAL R/C YACHT ADIO controlled yachting seems to be on the increase in the U.S.A. and we recently had photographs and details sent over of a commercial venture which could well prove extremely successful with the modelling-conscious market in that country. The model in question is a 55 in. glass fibre yacht, with a 94 in. beam and a total displacement of 164 Ib., plus radio control gear, spruce mast and a glass fibre hatch and cockpit as- sembly. The maker is D. R. Hartman of Argenta, Illinois, and one of the chief distributors is Octura Models, 8148 N. Milwaukee Avenue, Niles, Illinois. The full retail price is around the $100 mark, i.e., about £28, though if imported for sale here the duty. etc., would push the price to about £55… ! i.€.,a total for modern superhet four or six channel equipment of under 18 Ib., 10 Ib. of which is in lead. We gather that the hull is moulded in one piece with the deck, but mahogany planking to be glued over the deck is supplied in the kit together with a 6 ft. 303