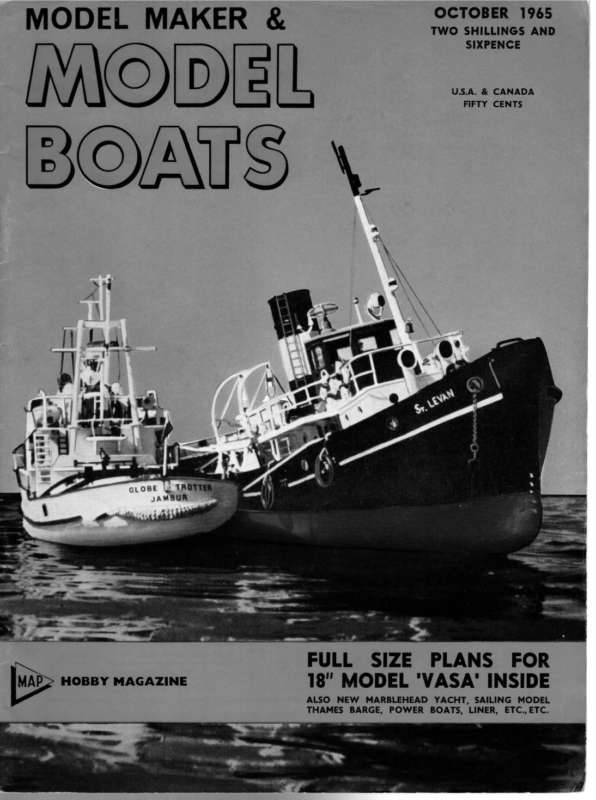

MODEL MAKER @& IO) D ) E MAb HOBBY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1965 TWO SHILLINGS AND SIXPENCE U.S.A. & CANADA FIFTY CENTS FULL SIZE PLANS FOR 18″ MODEL ‘VASA’ INSIDE ALSO NEW MARBLEHEAD YACHT, SAILING MODEL THAMES BARGE, POWER BOATS, LINER, ETC.,ETC.

MODEL BOATS HAMMER “The most powerful Marblehead yet de- signed” — developed from the successful Vega design concept By S. WITTY The boat in these photographs is a ‘Vega’ ALTHOUGH the built by C. W. Sykes of Bromsgrove (Model Maker Plan 759, 10/-) and named by him ‘Green Top’. Hull is rib and plank construc tion and the final weight came out exactly at the designed 16.5 Ibs. Mr. Sykes says he finds the boat easy to sail and she carries a spin- naker well. successful’’ He has, with he her, which, says, in been view “fairly of his winning the Midland District Championship and, up to the time of writing, a couple of Bournville club events as well, is somethi ng of an understatement! apparent from the that the boat is Not mentioned, photographs, is the original Vega M with similar type of fin and bulb keel, was largely an experimental design, those built to her lines since have shown how they are able to take on and beat boats weighing six pounds more. Inevitably this has led to speculation on what might be achieve d by applying this configuration to a hull of contem porary proportions. More important perhaps , is that as the majority of “M” craft are of approxi mately 11 in. in beam and weigh around 23 lb., most builders are not interested in a hull which does not seem to have the same “power”. Compared with a hull of similar beam and dis- but fact placement, beautifully built and fitted the design shown is over 65 per cent stronger, which should satisfy the most power hungry out, always a factor in racing success. skipper. Although it might be conside red that deeper Jateral area of the fin may tend to reduce stability, in fact in comparison with a normal keeler of 11 in. draught the mean centre of appendage areas is little different. The lines were progressively develo the the finthe ped from those of Hustler (M.M. May ’64) and to further improve the early planing characteristics, the bow sections are flattened slightly. This tends to make the run a little less flat, but as our ponds are of limited length, the ability to start planing early usually gives a decisive lead. In this respect it is difficult to decide to what extent the design techniques of manned planing craft can be applied. The deep chested type of hull tends to give forward sections which are too steep to retain any lift, extremely flat floored. unless those further aft are Bow design in a Marblehead is always something of a problem and an advantage of the more husky concept is that the sections can be full enough for’d to allow the hull to be driven really hard. Yet they are fine enough to avoid being stopped dead by a head sea, while still retaining a really attractive curve of deck line. Compared with previous, lighter designs of similar configuration it is unreasonable to expect such a powerful hull to be quite so easily driven. On the other hand the heavier boat will carry her way better and be more reliable in flukey conditions, In 410

OCTOBER fact the real problem is not to decide whether bulbkeel designs are superior in performance; they are, and must supersede other types sooner or later. What is more difficult is to know what are the best dimensions and displacement for optimum performance. For instance, as she is so powerful there will be a substantial gain in effective sail area when there is any weight in the wind. Tests at the Stevens Institute indicate that thrust is almost halved when the sailplan is heeled to an angle of 30 deg. So that even if this angle is reduced by 5 deg. for a given pressure, it presents a considerable gain in available thrust. It would seem this is the reason why “M” craft of different beam, etc., are often so similar in windward performance. The well tried and proven fin design remains very much the same, the slight increase in draught being due to the larger diameter bulb and marginally deeper canoe body. The stiffer hull sections also result in the fin and skeg being more effective so that possibly the area could be reduced. In fact, however, the total area is rather more, due to the slightly larger skeg-rudder. Dimensions are given for a shallow draught version, and this will still be more powerful than any fin keel “M”. On the other hand 1965 most of the premier events are held on waters with plenty of depth. To calculate the power of a yacht hull really accurately is a lengthy if not impossible business, and frankly in a model is hardly worthwhile. In any case, various assumptions have to be made concerning the centre of lateral resistance. For instance, although most of the lateral pressure is taken by the appendages, the hull must contribute to some extent, but there are so many variable factors to take into account that it is better to consider the fin and skegrudder only. Even then certain allowances must be made regarding the rounding of the lower fin keel or bulb. A good rule of thumb method of estimating the power of a hull is to multiply the maximum beam by the distance from the L.W.L. to the C.G. lead. It should be emphasised that this gives a figure for comparative purposes only, and holds good providing the centre of lateral resistance is about the same and the general hull design is not too dissimilar. Obviously, it would be unfair to compare a canoe stern hull with a transom type by this method. But whatever system of calculation is used there is no doubt that this design is easily the most powerful Marblehead yet. FULL-SIZE COPIES OF THE DRAWING BELOW, REFERENCE MM 832, ARE AVAILABLE PRICE 10/- POST FREE FROM MODEL MAKER PLANS SERVICE, 13-35 BRIDGE STREET, HEMEL HEMPSTEAD, HERTS. : SINCE THE PLAN LETTERING IS VERY SMALL IN THIS REPRODUCTION, THE SALIENT DIMENSIONS ARE GIVEN BELOW Ib. 14.25 LEAD KEEL : 13.6 in. DRAUGHT : 50.25 in. L.O.A. : 14 x 43 x 40 in. TOP SUIT, JIB : 797 sq. in. SAIL AREA : 48 in. L.W.L. : 17.25 x 50 x 51.6 in. TOP SUIT, MAIN: 21.5 Ib. DISPLACEMENT :~ 10.85 in. BEAM : easionee M corvaicnt oF MODEL MAKER PLANS SERVICE ame emo AT. HEMEL MEPETERS, omRTE,

BM MODEL BOATS KATE A SIMPLE 263 in. SEMISCALE THAMES BARGE BUILT FOR SAILING Hull Kate’s hull By Rev. J. G. M. SCOTT is 24 in. long, is very simply made, bread-and-butter style, from very old 1 in. pine, and her flat bottom is 3 in. marine ply, with a deck of zs in. ply laid on in one piece. Apart from a little “rocker” forward, which brings the bottom line up almost to the water-line and gives her a slightly less uncompromisingly crude entry, her lines are those of the traditional barge, taken from a number of photographs. Lee-boards, which would add drag and do nothing to help her sailing qualities, were omitted, and her fin, made from 4 in. marine ply, carries 22 oz. of lead. (Because I was not certain of my calculations of Centre of Effort and Centre of Lateral Resistance, I fitted this fin in a slot like a dinghy’s centreboard case, so that it could be shifted fore and aft, but my reckoning was correct and it has never needed moving.) Her rudder is deep like a dinghy’s, but as it and the fin are painted pale bluegrey below the line of the bottom, this is hardly ae many country parsons can afford to sail, and our N. Devon coast is too tidal for snatching the odd hour afloat; the only solution for one with a lifelong passion for sailing was to do it in miniature, and the first result is Kate. What I wanted was something to fulfil two main conditions: first, she had to sail well, and require no more delicate adjustments than could be made by my children; second, she had to look, on the water, as much like a real craft, and if possible a working craft, as possible. And as I had no experience in making sailing models, she had to be fairly easily made. The choice of a prototype almost made itself. The Thames spritsail barge, the largest sailing vessel in the world which can be handled by two men and a boy, has a rig which is simple but highly effective, and a hull which could hardly be simpler. With a fin keel and a few modifications to improve sailing quent there could hardly be a better beginner’s noticeable on the water. Rig The mast, housed in a tabernacle made up from scrap aluminium sheet, lowers in the authentic manner, but instead of a separate stepped topmast she has her mast made in one piece from @ in. dowelling. As its thickness is reduced abruptly above the crosstrees, and the “doublings” are painted white, it looks very good and saves weight and windage. The forestay is combined with the staysail luff-rope, passing over a small block (one of the very few paris bought, but I couldn’t resist it) and setting up with a bowsie on the fore side of the mast; there is one pair of shrouds and one pair of topmast shrouds —unnecessary really, but the spreaders are a very conspicuous feature of the original type. The mizzen model. has no standing rigging. Sails Sails are made from nylon, dyed russet with “Dylon”. They were cut with generous roach on leach and foot, and bolt-ropes are sewn into the staysail luff and the mainsail luff and head; the latter is fashioned into a loop at the throat for the throat seizing which secures it to the mast, and the luff is laced to the mast. The topsail, a big powerful sail on these vessels, has a headstick at the top, to which is fixed a small thread strop which fits over the tapered head of the top mast. The clew hooks to the sprit end, and the tack is set up near the foot of the mast with a hook and bowsie. This means that in a stiff breeze the topsail can be whipped off and stowed in a pocket in five seconds, and set again as quickly. Good and easy sailing demanded the only radical change from the prototype’s rig—the fitting of light 414

OCTOBER MAINSHEET— SK [ATTACHMENT Ye, CIMT, MIZEN MAST}: RUDDER _O- fz ‘ A a BOWSIE = ©) = GENTRING 1965 The hull is finished in black, with a yellow stripe at rubbing-strake level and a little scroll-work at the bow which, with the name-boards, was done in Humbrol paint with a mapping-pen. Masts and spars are varnished; the hatch-cover is covered with nylon and painted brown, the nylon having sufficient overlap to be secured round the coaming with an elastic band. Even with solid water over it, it takes very little water inside, and a small hole in the deck right in the bows allows this to be drained out very easily. booms to mainsail and staysail. They aren’t aggressively obvious, and they save a deal of fiddling at the water’s edge with wet hands and tiny gear. Sheets are set up with bowsies, the staysail sheet running on a horse-rail, the mainsheet working the steeringgear. Steering With the mizzen-mast stepped immediately for- ward of the rudder-head, no normal automatic steering would be possible, and I was not prepared to use the mizzen as a vane, because Thames barges don’t run downwind with their mizzen-booms pointing straight ahead. After some experimentation, a simple and quite effective gear was evolved which will keep Kate on any point of sailing, even an almost-dead run. The mainsheet works a “tiller”, pivoted at its forward end, and operating the rudder through a linkage made from a size 16 knittingneedle. Adjustable-tension self-centring is provided by an offset hooked arm on the rudder-head to which is attached one end of an elastic band, the other end of which is hooked to a line which can be set up with a bowsie along the port side-deck. To this bowsie is also attached another line which passes through an eye on the centre-line just below the after end of the tiller and is made fast to the tiller, so that when the bowsie is set up hard this line centres the tiller and locks the gear for sailing closehauled. , Considering that she has the grace and subtlety of line of a shoe-box, Kate sails remarkably well. Off the wind, she pushes up a big “bone in her teeth” and rushes along with the characteristic lift of her weather quarter which can be seen in many pictures of her big sisters. Close-hauled she is not fast, but slips along easily enough in light breezes, and in heavy weather butts her way through a cloud of flying water in most impressive style. Even in conditions when she couldn’t carry her topsail and still had her lee deck continually under water she thrashed her way the length of Sandy Mere at Northam through a vicious lop, instead of sagging away to leeward as so many home-made models do. The only parts bought were the staysail halliard/ forestay block, the horse-rail, and shroud hooks. The bowsies, for the sake of invisibility, were made from Perspex, and the steering-gear put together from various odds and ends of Perspex and scrap brass, as I have no experience of soldering or brazing. On the water she looks very pretty, as I think the pictures show; were it not so, I would not have ventured to offer a beginner’s effort in such an experts’ forum as this. But as a compromise between the last-detail prototype model and the out-and-out racing model yacht I hope that she may be of interest to the experienced and encouragement to the beginner. 415 AAU

M1 MODEL BOATS es NOTES FOR THE NOVICE (-) MODEL YACHTSMAN (0 liA Part Ten—The Moving Carriage Vane Gear Fig.33 By A. Wilcock gs Bere fourth and last type of gear to be described is the moving carriage gear. This gear as distinct from the previous ones is of British origin and of a later date. In the author’s opinion it has much to commend it. It has the following attributes: (1) It is easily balanced. (2) It gives positive helm to Lee and Weather. (3) It is positive in tacking. (4) Its angles of self tack can be adjusted precisely and independently for the two tacks. (5) Its guying action is as good as any. (6) It is robust. That is enough. The whole principle of operation is entirely different from any of the others and since the author is aware that it presents difficulty to some potential users, it will be described from first principles. To an engineer it is a SUN and PLANET motion, so to start with let us place two pennies on the table side by side, heads facing the same way, in the position of the cireles in Fig. 32(a). Holding the left hand one still, with a finger of the left hand carefully roll the right hand one round the stationary one to the position shown in Fig. 32(b) and then on to the position shown in Fig. 32(c) and notice the position of the head. By the time is has got to Fig. 32(b) the head is upsidedown, ie., it has rotated 180 deg. while moving through 90 deg. relative to the stationary penny and by the position of Fig. 32(c) the head is upright once again, i.e., it has turned through 360 deg. while rolling 180 deg round the stationary penny. Turning now to Fig. 33 the pennies have been replaced by identical gears and the means of rotating the moving gear is supplied by mounting it on an arm, or carriage as we call it, pivoting round the shaft of the first gear. The latter gear is called the SUN wheel and the moving one the PLANET. Moving the carriage either clockwise or anticlockwise while holding the sun wheel will cause the moving gear, the planet, to behave just as the coin did. The gear will turn through twice the angle that the carriage moves through. Now we couple the sun wheel to a rudder which, for a start, is held central relative to the axis of the boat, and we mount a vane feather and counterweight on the planet gear, in line with the carriage and the gears and the rudder. This is illustrated in Fig. 34. Consider for a moment that the rudder is fixed in line with the skeg and we move the carriage through 15 deg. to one side. The vane will move through 30 deg. Just what we want for our self tack motion. If the carriage is moved 15 deg. in the other direction the vane moves 30 deg. in that direction. Now think of the carriage being temporarily secured in the 15 deg. position and free the rudder; any movement of the vane will be transmitted through the gears to the rudder as a positive drive either to LEE or WEATHER. That is just how the moving carriage gear works. To give the carriage the required movement it is coupled through a cord ‘bridle’ to the main boom, and to adjust the vane angle on the tacks adjustable stops are put on each side of the carriage to determine and limit its angular motion. Fig. 35 shows the details of a practical design based on these principles. A moving carriage vane gear was first described by the author in the Model Maker, Februrary 1961, and let it be said that there is nothing wrong with that design—the present one is merely a variation on the theme, just as one gets variations with the other forms of gears. Turning to the parts as coded in Fig. 35 “A” is the rudder post with quadrant for gybing just as with the previous types of gears described, “B” is the main pintle on which the gear is mounted, “C” is the carriage which fits on the main pintle. It consists of a tube “H” which is a reasonable fit on to the pintle and has in its top a conical bearing. Carefully spaced a pitch diameter of the gears away from the centre of the tube is the pintle “D” to carry the planet wheel “E”. This wheel is fixed to a tube “K” with a top conical bearing. The scale is clamped to this tube to permit final adjustment for fore and aft alignment when the gear is fitted to the boat. The vane and counterweight assembly also fits on tube “K” with an adjustable clamp which permits it to be adjusted for correct frictional movement when the gear is being used in the fixed condition. The sun wheel “F” carries the arm “G”. This combination is made a nice clearance fit on tube “H”. The arm is designed at the gear end to cover the gear teeth so that it will prevent the tube, on which the planet wheel and vane are mounted, lifting off when in use. It also acts as a limiting stop. The sun wheel is in turn prevented from lifting off by the collar above, secured by a grub screw. The cross arm “J” used for giving the tacking motion is secured to the carriage at the pivoting point. The gear motion is transmitted to the rudder via a push pull rod attached to the arm on the sun wheel at one end to the quadrant at the other. The angle of movement of the carriage when in the “broken” or self tack condition is determined by the two stops which are on the threaded rod attached to the carriage. They “catch” on a stop on the main base. At the other end of the main base is a scale for observing the angle of the carriage—this is half the vane angle as will be apparent from the introductory remarks. The locking catch is also at the back end of the base in the form of a slider which, in the forward position, engages the tail 428

A) 6¢P ANVTd ONIN NI FAT g¢ B14 *peyddns aq uvo sjuauyejsur FILSV TF INIGLWID NIT HOVP AND snolaaid Jje 10J sioquinu yorg pue anssi ee S96] Asenuee 9y) UI UBsaq satis sity ESOC 4 8 SSS ‘sjuapuodsaii0o jo Jaquinu & 0} Ajda4 uy [penuinuo> aq of] ‘sdojs 94} Suruin} Aq opis yove uo ‘Sap {] JO OT 0} JUSWAAOW dSeIIIvD 9y} sn[py ‘10d 0} Usy} pue pivoqiej}s 0} JsIy uOoTIsod [eUus. 9Y} WoIy poaow SI O8¥IIIVD 9Y] SB o[BdS OBeLIIeD oY} UO podj}LoIpUl SB 9[8UL SY} SdIM] 0} SOAOW DUA 9} }eY} 99S puL AMYVTI 40S GILLINO B INVA 4LHUIIMAYTLNNOD yo}e 94} YooruN IMT HIVL AND ON/ILVIE ‘[eNUSd psy JOppni sy} YIUAA OG 24} JO SIXE 34} O} SATLIAI PIVMIOJ “BOP OR] Oy) pur ye SI Sulyieu ‘sap () 9y} }eY} OS pajsn{pe oq mou Plnoys ayeos ay} UOT}Isod psyoo] 9Y} UI Yd}ed BUTYDO] 94} YUM Yop oY} O} Ivas oY] Jo sseq OY} poINdes pue po [[nd ysnd jo yysus] Ys oy} poy Sulaczy ‘[e04M Jourld 9y} Jo Y}90} 94} YsuTeSe BuIddo}js wie 94} Jo pus Ivas oy} Aq UOTDAJIP IoYyJO 94} UI pue 9qn} yorq 9Y4} SUTYINSs Wie oy} Aq UOT}DeIIP suo UI POW] SI JUDWISAOW Ie[NSue SIy] ‘UOTOW OTS pue uld & YIM J[QRITeAe SI URY] SIOUI ‘JUSWIOAOW JOppni ajyenbope sald [IM Wie Ivos 94} JO JUOWSAOW IepNsue jo osuvi oy} yey} puNoy aq Udy} [IM I ‘GuouNsnl -pe Jayjo Aue ynoyWM sone mod Joie ApsAooys ued noA Udy} UIOd sIy} Wo SIe Ue UO ov JUeIpeNb ey} UO suUOTIIsod sAteUIA}[e 394} JI) }eOgG 94} Jo sul] 913U99 9Y} 0} sojsue }YSII je ploy Wie Ives oy} UO joAId 9Y} 0} ([eNeU Ioppni pue jueIpenb 94} YIM) asn 0} 3ulos oie noA jueIpenb 94} Uo jyuIOd 9y} WOIf} poInsvsul 9q ued pol [[nd ysnd Jo ysua] 94} ‘res 94} a0ejd 0} YsIM noA o1oyM poploop B3UuIARH ‘jsoq Ivos pue jeoq INOA sjIns yeyM puy ued nod juvipenb 94} UO UoTIsod suo UeYy} sIOW sAey NOA JJ ‘por tjnd ysnd oy} 10J ssurseds jenbo YM O1j}e1 eos [:%] eB se poo owes oy} Ayjeonovid sey siyL ‘Ieo3 94} UO We SuNeiedo 94} Jo YJsUsT oy} SOW} yyey eB pue suo st jsod Joppni 94} Woy JueIpenb oy} 0} por yind ysnd oyi jo yuowYoORye jo jyulod 2Y} JO SoURISIP 94} Jey} POpusWIWOSAI SI WI [:][ 3} SUISn USYAA “[:] UeYy] One IOysIy Be YM OTR -sI}¥s puy SIoyjO ey] oIeMe IOABMOY SI oA, ‘jouRTd oy} ouO Jo][eWIS Sy} pue JOe4YM UNS 9y} BSUIOg IeOs Josie] oui) [:¢ 0} dn sonnel jUsIOyIp YM poyuow -lIodx9 SuUIARY ‘ONeI [:] Sy} pUusWWIODeI prnom Joyjne oy} pue pdajensnij]l useq sey sfeoym eos pozis [enbo Suisn 1vos YW ‘[Iesuleu oy} Jo UWeomsdiys oy} WOIJ dUvA 9Y] SuUIIeI]D Os jsod Ioppni sy} Jo ie [Jo Ives oy} coRj[d 0} Udye} 9q Ud AyIUNTIOddO 93} sse[d Y IO Y OT B UO ZTIYM ‘AeMe YOU Ue UeY} sso] pojunow oq Aeur 1e03 oY} WosueI) 9y} Ieou AIDA 9q Aeur Joppni oy} o194M speoys[qiep, pue Y “Ul 9¢ UO sny], ‘sieved 104}0 YIM [eNsN UOT}OW jJoO;S pue ud 9y} yym poredwios jsod Joppni oy} 0} 9ATRIOI Ivos oueA oy) Suluontsod ul Ajyyiqrxoy Jayeois yonuw syed IOPpNI 9Y} 0} JUSUISAOW SUA 94} JUWISUI] 0} posn SI por qnd ysnd e& iy} Wey OY ‘}eOq & UO JUOWUSITe oy} 0} UN} OM syed 34} Ppoqliosap MOU SUTARTT T3ZHM Od “isis tae . $96L WABOLIO —~ a . ‘1e93 94} JO UONvIsdo 94} UI paqiiosap 9q TIM yorum sAnB oy} smoys osye i] “Teas 94} UO Ieq BUTYOR}] 9Y} 0} WIOOG 94} WIOIJ JO9Ys SuIeIq 9} S}DOU -U0d PIOD dUaTAIO] JO IIPlIq 94} MOY SUIMOYS MOIA uvjd & SI 9¢ “SI “SOOIOJ PUIM YIM J[sUe BSUS O} jou Ysnous suIddis a1yM o[sue Aue ie pouontsod aq 0} HW ajqeue Oo} 9qn} 94} UO dius uO e Aled} -uad sey if ‘om3y oy} WOIJ Iea[d 3q [IM A]quiasse J]YSIomIajUNOD pue UPA SY] ‘BSeIIIVD 94} JO IsjUIOd