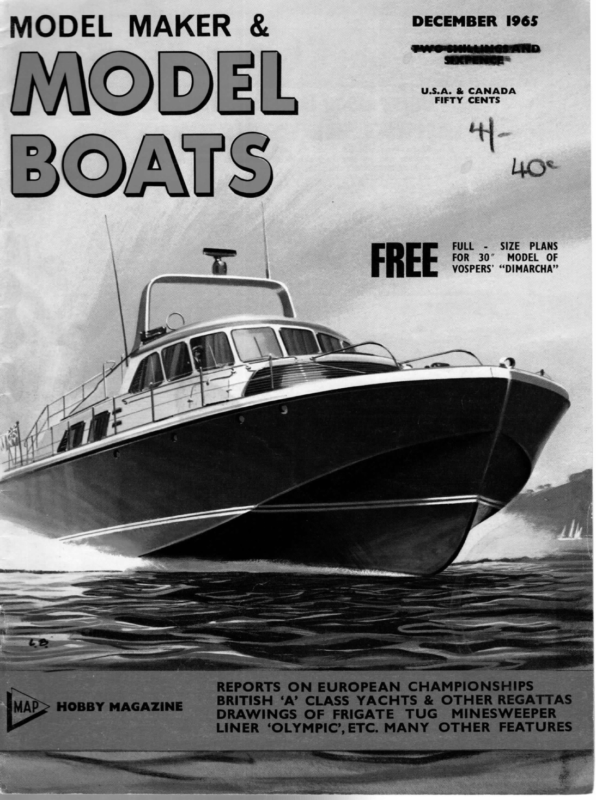

MODEL MAKER & DECEMBER 1965 — U.S.A. & CANADA FIFTY CENTS rey FULL – SIZE PLANS FOR 30” MODEL OF VOSPERS’ “DIMARCHA”

C SE MODEL BOATS 1965 BRITISH OPEN AND INTERNATIONAL ‘A’ CLASS CHAMPIONSHIPS Fleetwood, 8-15 August Photos by L. Dewhurst BY. one of those ironies of fate, the bad summer of 1965 produced one week of hot, sunny weather and light, variable south to south-easterly winds, and this week coincided with the A Class Championships at Fleetwood. It also coincided, incidentally, with the move of M.A.P. offices from Watford to Hemel Hempstead, which meant that we were unable to witness the regatta. Because of the heat, the regatta was a tiring one and, for the skippers, the direction (not the best at Fleetwood) strength, and fluctuations of the wind were somewhat frustrating. On the opening day, Sunday, a 6 knot northwesterly was reasonable, but on Monday it was all round the clock and very light, Tuesday and Thursday light S.E. (giving a reach at Fleetwood) and light easterly on Friday and Saturday. These conditions suited the Pollahns from Hamburg very well; they were sailing the original Moonshine, bought a couple of years ago and since refitted and equipped with a large outfit of assorted-flow Dacron sails, flexible mast, etc. Moonshine was thus superbly equipped for the con- ditions, and sailed by a crew experienced in similar conditions and with a meticulous regard for detail. In one of the closest races for years, she opened a slight lead on the first day and, despite a number of fine boats being always within striking distance, maintained the lead throughout the week. Only on Thursday did she fail to hold top score; Ayala’s 41 points from Tuesday night to Thursday against Moonshine’s 30 put David Wilkinson two points ahead, but the challenge faded in the different conditions of Friday and Saturday and the German boat finished nine points ahead. A glance at the daily totals shows that differing weather must have produced a completely different picture. Take Outlaw, lying second at the end of the first day, obviously unhappy when the wind dropped, Munin, apparently unsettled initially but finding her trims after mid-week, Colleen Dawn and The Saint recovering from shaky starts to be within striking distance by Friday—Friday was obviously the crucial day and Moonshine showed her consistency and adaptability by taking 25 points to Ayala’s 18, Juanita’s 23, Satanita’s 25, Colleen Dawn’s 25, and Bingo Cat’s 23. Naturally, the “luck of the draw” comes into any day’s sailing, and the score figures do not show whether a board was won or lost by half an inch or half the lake. The leading boats indicate quite an assortment of design with Daniels to the fore. Moonshine is the name 502

1965 DECEMBER design by Lewis, Ayala a modified Jill by Daniels, Juanita also a Daniels. The Saint is another modified Daniels, Bingo Cat and Reward both Highlanders. New boat Satanita is unknown to us, though we have heard it has tremendous tumblehome and striking windward performance. Possibly a development from Juanita ? Of the top boats, this is the second year running that Ayala has placed second, Juanita has had two 3rds and two 4ths in the last five years, and The Saint placed 3rd last year and 4th the year before. International Six countries again contested the ““Yachting Monthly” Cup and two rounds were sailed on Saturday afternoon and Sunday, the wind having swung to light westerly. The Belgian boat, a glass-fibre Highlander, collected 9 beats and 6 runs to notch up Belgium’s first win, with Moonshine only three points behind. Ayala produced the fastest run at 3 mins. 1 sec. to collect the Wing and Wing Cup, coming third overall, and the winner also received the Johnny Cup for the highest number of windward legs won. Heading photo shows the winning German team talking to Arthur Levison. Top left: George Leeds sending Bingo Cat and Ayala off on a run. Bottom: Colleen Dawn and Jullanar, Right: Kitty Cat and Ulster Lass. Far right: Ayala typifies the unusual wind direction and strength—from the background the wind must be between S. and S.E. and somewhere between run and reach. M.Y.A. BRITISH OPEN “‘A’? CLASS CHAMPIONSHIP, FLEETWOOD 1965 Position ip 2: i 4. 5. { 7, 8. 9: 10. 12. 14, 15; 16. { 18. 19, . 20. 21. 22. { 24, 25. 26. { 28. 29, 30. 31, 34, 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. No. Gi18 K796 K720 K824 K787 K797 B35 K743 K619 K784 K789 K788 K806 G125 KS17 K800 K803 K817 K712 K790 K811 KS2 F45 K819 K731 G115 K779 K677 K772 K771 K679 K802 K822 B36 K816 G106 KS795 K463 K823 KNI770 KS9 Name Moonshine Ayala Juanita Satanita Colleen Dawn The Saint Bingo Cat Reward The Stranger Munin Phillipa Drumbeat Merseybeat Hamburg An-Eala Outlaw Tuppence Telstar Jullanar My Ninepence Kai-Sara Viola Patricia Agamemnon Aramis Imme Red Gauntlet Maybee Serenade Elvira Vanity Fair Confusion Chaser Kitty Cat Flamenco Caribee Kiltie Barika Aries Ulster Lass Gaoth Nair Owner FINAL RESULTS Club Germany Fleetwood Clapham Bournville Gosport Bournville Belgium Clapham Gosport Y.M. 6m O.A. Y.M. 6m O.A. Y.M. 6m O.A. Birkenhead Germany Greenock Fleetwood Birkenhead Gosport Gosport Birkenhead Fleetwood Saltcoats France South London K. Pollahn D. A, Wilkinson C. Dicks J. Mier A. T. Schollar D. Lippett G. Van Hoorebeke R. J. Burton R. Gardner V. Knapp A. Levison E. Porter K. Jones Fr Jacobsen H. Shields W. M. McIntyre P. Mustill P. West L. Davis F. Amlot E. G. Leech T. Buchanan H. Boussy W. Jupp W. Hugman W. Meyer J. O’Connor W. Farrer H. Francis K. Dight N. J. Fish D. A. Armitage H. Atkinson J. De Schrijver Fleetwood Germany Birkenhead Leeds & Bradford Gosport Y.M. 6m O.A Clapham Birkenhead Leeds & Bradford Belgium Birkenhead Germany Victoria West Gosport K. Roberts H. Kretschmann W. K. Rodrick D. Lording Fleetwood Ulster Saltcoats J. W. Roberts R. H. Tregenna H. Miller Sun. 27 15 14 12 15 16 21 20 20 13 11 11 15 21 16 25 15 15 16 11 11 11 21 19 18 17 6 24 15 10 10 7 8 11 5 20 11 13 15 6 13 Mon, 49 37 27 27 36 40 35 30 36 25 37 31 34 31 36 33 37 27 27 33 22 28 37 38 31 27 19 36 24 27 25 16 31 22 7 37 20 27 23 11 21 Tues. Thurs. Fri. 79 109 134 = = 70 111 +129 99 122 58 52 64 72 57 57 63 48 63 47 50 55 52 58 56 50 42 50 42 41 57 56 47 44 41 46 38 42 41 37 45 37 50 53 27 37 34 23 41 96 105 108° 95 94 $3. 95 99 91 $42″ 78 83 84 80 69 71 79 66 73 81 82 715 71 62 70 59 69 67 68 67 68 70 57 55 59 47 50 YACHTING MONTHLY CUP Final Results (Two Rounds) 1. pd, RE 4. 3: 6. B35 Gi18 K796 KS17 F45 KNI770 Bingo Cat. Moonshine Ayala An-Eala Patricia Ulster Lass G. Van Hoorebeke Belgium H. Shields H. Boussy R. H. Tregenna Scotland France Ulster K. Pollahn D. A. Wilkinson 503 Germany England 39 36 29 22 15 6 Sat. 143 134 130 121 129 120 128 “123. 128 118 126 118 123 112) 122 112 116 114 116 112. 112 102 ~112 #106 = 111 98 105 102 104 =101 104 96 =103 94 102 98 91 97 90 96 88 96 96 95 95 89 87 89 80 79 85 81 76 79 80 719 81 72 67 61 60 58 94 92 92 87 86 85 84 84 84 83 83 81 79 67 66 63 60

MODEL BOATS ALLOY TUBE. AND FRAME NOTES FOR THE NOVICE ~~ WORM PINION MODEL YACHTSMAN—12 TOP PLATE TO GEARBOX —<—— i s- = WORM BOX A. Wilcock finishes general model advice and closes by giving some interesting comments on vanes for full-size yachts. A NOTE now on pin and slot motions. It was mentioned in an earlier section and must be reiterated here that whenever a pin and slot motion is used the pin must be on the driving member, thus when it is used between the vane gear and the rudder the pin is on the vane gear and the slot is on the rudder (quadrant). When used between the feather and the counterweight the pin is on the counterweight side since it is the counterweight moving over under gravitational force that moves the gear over from one tack to the other. Pintles and bearings deserve special mention because the free operation of any gear is almost certainly dependent on its bearing surfaces. Pintles can ‘be divided into three classes. Vertical with the point upwards on which something is “hung”, vertical with the point downwards which is supporting something, and pintles with a point at both ends supported usually between conical cups. The former two both require a second bearing surface which is usually a bush or sleeve bearing. Bush or sleeve bearings are types where there are parallel surfaces in contact. In the author’s opinion they can be put in the following order of preference: (1) The vertical pintle with the point upwards, with a small area of bush bearing near the base. The taller the pintle and the greater the distance between the point and the bush at the base the better, Fig. 41a. (2) The double pointed pintle, operating between conical cups whose distance apart can be precisely adjusted, Fig. 41b. (3) Carefully proportioned bush or sleeve bearings Fig. 41c and (4) The vertical pintle point downwards Fig. 41d, This is the last because of the relatively high bearing, point “X’’. A glance at the illustrations bush bearing, point “X”. A glance at the illustrations of the gears described will show the situations in which the various forms are used. Top and bottom pintles are definitely recommended for rudders. A word now on “fits”. This is an engineering term relating to the closeness with which the parts fit together. Let it be emphasised that for satisfactory vane gear operation under all conditions—especially after a few dippings in salt water—a slack fit must be used. The author is aware of numerous precision engineer-made gears that “gummed up” very quickly in the above mentioned conditions because water is not a good lubricant. It is also particularly important, if you are going to have your gear plated after completion, that adequate allowance be made for the thickness of plating. If you are going to sail frequently in salt water it is well worth while having your gear chrome plated. In other circumstances it is nice but rather expensive to have done. Free movement of the gear under all conditions is of paramount importance. It should be such that wafting a newspaper six feet away will cause it to operate. This means clearance fits not only on pintles and bearings but also on pins in slots and the 516 PTFE BUSH ~— DECK FLANGE KEELSON FLANGE meshing of gears. These features will show up on the bench as backlash or slap in the overall movement. While this should not be excessive, it is of no detriment when of the appropriate order, since when sailing—and this is important—the gear should be set to be giving a minute amount of helm and therefore the slap is taken up. Additional wind pressure in the same direction is against a firm motion and in the other direction the removal of that small amount of helm immediately starts the correcting movement. It should be appreciated that the wind moves constantly more degrees than the slack of your mechanism if it is of the right order. Watch the weathercock on a tall building. The author passes daily the London weather centre and watches their weathercock, and its gyrations are amazing. Where possible avoid side pulls on bearings. The centering line is a particular case where the elastic can pass through a hole in the member being centred, whether it be a tail on the gear or quadrant, and side pull practically eliminated. Gears (of the toothed variety) when you use them, should be of the best cut teeth you can readily lay your hands on, although Meccano gears have been used and proved adequate. Avoid meshing them too tight—a bit of sand or grit can play havoc with their performance in those circumstances. For guys and centering lines, shirring elastic, obtainable at Woolworths or any haberdashery store, is recommended. It can be obtained in more than one thickness and the textile covering preserves the elastic well. Otherwise, use elastic bands which are very cheap. Some people use fine stainless steel springs, and these are excellent until they are accidentally overstretched when you are in much more trouble than if you carry a packet of elastic bands. Hard brass is recommended for the construction of vane gear mechanisms. A look round the curtain rail counter at Woolworths will furnish quite a variety of pieces. Hard soldering, using Johnson Matthey Easyflo flux and No. 2 swlder with a Davi-Jet

DECEMBER obtainable at about 5s. from any good tool shop, will give a most robust job and with a little practice, is not difficult. Parts screwed together and then soft soldered is a second best, while soft soldering only can hardly be recommended at all, particularly if salt water is to be encountered. Too often has the author seen soft soldering let down a skipper at a crucial moment in a race. One sees other materials used in the construction of gears such as Perspex, Formica, Tufnol, and aluminium. Because they are not so strong as hard brass, greater cross sections of material are necessary for adequate strength which makes the gear more bulky and it is not so easy to get robust joints. The author has tried most with varying degrees of success but today favours BRASS. The Vane in Full Size Practice on It is proposed to close this series with a few notes Automatic Vane Self Steering applicable to full sized craft. This would be presumptuous but for the following two reasons: (a) It cannot be denied that it is model yachtsmen who have experimented and developed over many years this form of steering. (b) That famous single handed ocean racer Francis Chichester sought the advice of members of the author’s club before equipping Gypsy Moth III with “Miranda” for his single handed ocean racing. In these circumstances the author humbly feels some justification in making the following observations. To those skippers who have followed the series, it must be evident that, though we may appear to be wishing to do the same thing, our problems, while having a similarity, are in fact quite different, and it is hardly correct to say we are trying to do the same thing. As was pointed out in the section in the March issue, the complications of the racing model yachtman’s gear are brought about by the tacking and guying requirements to avoid being penalised in racing to the M.Y.A. rules. Basically then, vane steering for the full sized yacht can revert to the non-self-tacking gear which is inherently much simpler. Nevertheless, it is quite clear from reading and thinking about the requirements of the full sized boat that there are many problems. The first is that one cannot manage a “feather” of anything like the proportions we use on model yachts. The second is that few, if any, designers of full sized craft achieve anything like the balance that has for so long been a characteristic of our models. How far the resolution of the vane steering problem will await different, one almost says better, hull designs with accompanying sail plans remains to be seen. There may well be a parallel here to the introduction of vane steering to model boats designed round the requirements of the old Braine steering. The changes required may be just as radical. One point that should be emphasised to our big brothers from the outset is that vane steering, as conceived for model boats, steers the boat at a constant angle to the apparent wind, and it is inherent in its conception that it does not steer a compass course. It cannot because it is wind operated. Within the author’s knowledge a device to sail a fixed compass course—which would be very useful to model yachtsmen as well as full sized—would require “apparatus” which would contravene model sailing regulations, and no doubt full size. Turning now to the problems of physical design, we will first deal with the below water aspects. Much depends on the position of the rudder on the hull, 1965 ie., whether it is on the transom or hung on the fin, either vertically or inclined but well tucked under and, of course, whether the transom is vertical or inclined. Just as we model yachtsmen had to change our underwater forms to obtain maximum advantage from vane-steering so it may yet be found that this is necessary in full size practice, particularly as regards hull balance and developing partially balanced rudders which do not require such great effort to operate them, i.e., they have a proportion of the blade forward of the rudder post. The positioning of the rudder to obtain maximum turning moment with minimum effort, as is so frequently met with our Marblehead designs, is an important factor in the overall design. Three basic rudder arrangements seem to offer practical solutions, namely (1) a plain rudder, whether it be the boat’s present rudder, or one more suitable for vane steering—see the changes made in model design between Braine and vane steered boats —situated at the optimum point under the hull body. A partially balanced rudder situated well aft is the author’s opinion, unless the fin is narrow, when the hull is tender to steering from a long narrow rudder placed on its after edge. (2) An auxiliary flap or rudder on the after edge of the boat’s main rudder. Because of the difficulties of operating such a device on a main rudder tucked well under the hull, this arrangement is more applicable to a rudder well aft and projecting beyond the transom or actually hung on the transom. (3) An independent supplementary rudder associated directly and only with the vane mechanism. This can be associated with a main rudder situated in any position under the hull providing there is a clear space for it to operate in and it can be of the semibalanced type or provided with a skeg as has been found to be of such great advantage in the model yacht form. It is evident from what has been published in the yachting press that all these arrangements with variations on them are being used. To those who have followed the series from the start it will also be clear that the balancing of the underwater parts is just as important as the vane assembly. If not balanced against heeling and pitching, then they generate forces which may be in opposition to the vane on the average for 50 per cent of the time. This balancing is much more of a problem with a full sized boat than a model but it cannot be ignored. One is prompted to ask the question, in the case of the supplementary or tab rudders, if the tab rudder is capable of holding the boat to a course under the control of the vane, what is the main rudder doing, or for? The reply would almost certainly be, that it has been preset to the average helm required by the course, and the tab is a vernier. In the author’s opinion such an arrangement suggests a lack of balance between hull form and sail plan which call for frequent adjustment of the main steering to meet the varying wind conditions and it is questionable whether the overall combination will 517

MODEL BOATS ever be better than an expedient. It can cast as much doubt on the efficacy of vane control, as was experienced in fitting vanes to previously Braine steered models. Fundamentally, the aim should be to alter hulls and sail plans so that the vane can operate the rudder. Attention water line” can now details. It be is directed presumed to the that a “above similar principle applies to what is acceptable within the spirit of the rules as applied to model yachting. While the author is unaware of where this may be found in regulations and he is aware of the controversy that raged between the anti-vane and pro-vane advocates on the introduction of automatic vane steering to models, it can most simply be stated that the whole of the energy should come from the wind. This bars wound spring or electric motors whose stored energy could be released as required and almost certainly wind motors as well, unless the energy is for immediate consumption. This is, however, where the whole question becomes controversial, for what is a motor and what isn’t? Certainly the model yachtsman stores energy derived from the wind on the vane in the springs (metallic or rubber) he uses for his guys and uses this stored energy to operate his gear at a later point in time. Some would say the vane is a motor! This is food for thought and we must leave the discussion there. In spite of the anti-vane parties with their desire to include the vane area within the measured sail area, today it is recognised that a vane, used for the purpose for which it was designed, does not add propulsive effort in the way of additional sail area and so it is not measured. The fact that it is now recognised as contributing a drag factor limits its size in the model yacht case to the smallest effective area, although it would seem that this is very arbitrary. As was mentioned at the beginning of this section, the vane gear for a full sized boat can omit all the complexities of the model yachtsman’s self-tacking gear and guying arrangements and revert to “square one”, the simple balanced gear. It is not proposed to review the various forms that are currently in use, which has been done so ably from time to time in the yachting press, but rather postulate one design only which the author, from his experience in the model field, considers offers scope for general application. Fig. 42 illustrates what is in mind, complete and in exploded form as has been used throughout the series. The mast (pintle) in many ways is the heart of things, for if that fails all else fails. Its fixings must be firm and as long as possible so that it should, wherever possible, go through the deck to the keel- son or, on a deep transomed boat, down the transom outside or in. Mounted on this is the vane or feather. Since, while this should have pressure on one side or the other most of the time, there will be enough occasions when it will “slat” in the wind and a sail like a mizzen would shake to ribbons in no time, if a canvas vane is used it should be supported on a frame. This is attractive as it is relatively light and it can be reefed. For a sea going boat there is a mighty lot to be said for that. The coupling between the vane and the motion to the rudder of whatever type and wherever situated is one part that carries an enormous strain. It needs to be capable of a 360 deg. motion relative to the rest and be quite solid in any required position. The proposition is a worm gear as illustrated. The worm is naturally on the quadrant since this has normally little more angular movement than the rudder and therefore can be placed where it is always accessible. This also seems the appropriate point to disengage the vane when under manual control; an essential requirement, and the vane is then free to fly in the wind and the canvas to be reefed or removed. The adoption of a wire linkage between the vane quadrant and the rudder gives maximum flexibility, as well as the means to adjust the leverage between the vane and the rudder, whether it be the main rudder, an auxiliary or a flap (tab). For the latter it is suggested that it is always operated back to a “centre” on its rudder’s main post and coupled from there to the vane control. Balancing is just as important as on our models and because of the 360 deg. movement, can only be done in the conventional way—above the deck and opposite the vane. The C.G. of the weight must also be movable if the vane is to be altered in size unless parts can be removed. On this point it should be restated that when vane steering was introduced to model yachting some skippers advocated different vanes (feathers) for different winds—experience has shown this to be unnecessary. There are, however, clearly occasions at sea under “bare poles” when it would be most desirable to remove all possible windage from the vane and the counterbalance. REGATTA REPORT (continued from page 522) The second event was Speed Steering over a figureof-eight course, the loops of the eight being formed by pairs of buoys. This event was won by D. Careless, of the home club, with Mr. Lewis, of Brighton, close behind; the third place being taken by R. Mogg, of E.M.I. The third event was a Novelty, where a boat towed a marker buoy on about 6 ft. of nylon line. G. Portlock won this event very comfortably, his time being 1 minute over the same course as the second event. His nearest rival was 18 seconds behind. On a jocular note, it was interesting to see “Johnnie” Johnson “having a go” in the steering event, but only when the sun eventually decided to show its face—what’s up Johnnie, frightened by a drop of rain? Of course, as usual, Alan Greenfield was still “tuning up” at the end of the day—lI think he ruined about four props during the day before he decided they did not take kindly to hitting the concrete sides of the water at about 20 m.p.h. We do, however, most sincerely thank all competitors for their endurance during the first event when the rain was very heavy indeed.—T.G. Final Results: R/C Hunter; 3, J. Steering. 2, R. Husband E Mogg class: (PM), 1, T. Greeman (PM), (E.M.I.), Oliver Tiger Major; O.S. 19. D. class: 1, Mr. Walker (V), Miles 5 cc.; 2, F. Elwell (PM), Miles 5 cc. C class: 1, D. Careless (PM), O.S. .49; 2, M. Harvey (WT), 8 cc. (Merco, I believe). B and A class: 1, J. Till (PM), Gannet; 2, G. Portlock, Home-built 15 cc. Petrol. R/C Speed Steering: 1, D. Careless (PM), O.S. .49; 2, Mr. Lewis (BT), Unknown; 3, R. Mogg (E.M.I.), Oliver Portlock, as above. 518 Tiger Major. Novelty: G.