_ Model Ships- Cars – Engineering

MAY 1963 The Airflow around Sails leads to some conclusions By Lt. Colonel C. E. Bowden A.l.Mech.E., C.R.Ae.S Wool Tufted Sails Show the Airflow Pattern Airflow patterns around wool tufted sails of model and full-scale yachts under sail can provide important clues in sheeting for efficiency and the development of yacht sails, particularly if allied to wind tunnel measurements in the new slow speed tunnels that can take sails up to around 8 ft. in height. Thus, an examination of the windward side of sails in action indicates where the maximum “flow” of the mainsail should be situated to allow for “mast interference’, and the result of the wind’s deforming effect in windward sailing, whilst wind tunnel measurements tell us the best curvature for a jib. Airflow patterns seen on the important lee side have shown some unexpected results, and suggest improvements in conventional rigs, as well as stimulating unconventional rig experiment. The wool tufted sail tests I have made over the past two years, allied to wind tunnel tests mentioned in this article, leavened by racing experiences, assist in arriving at certain conclusions likely to be of use to model and full-scale sailmakers and yachtsmen. They also suggest further research. Considerations of space only permit a very few photographs from over 200 taken during my tests. Those shown give the main points of windward sailing, which is a vital factor in racing, as courses are set with the emphasis on the windward legs. These are probably the first combined wool tufted tests made on large radio models in conjunction with fullscale craft for purposes of correlation. The single sail cat rig shows up badly on the lee side, which everyone today knows is a very important “suction” side of low pressure drive. Subsequent experiments have indicated that attention to a special leading edge, and double luff sail can improve the flow of a single sail. The non-overlapping jib used by model yachtsmen shows up equally well as the short overlap foresail. This article has been divided into two parts, which should be read together if a full picture is to be obtained. Large Model Yachts are Proved to be a Reliable Guide to Airflow Patterns Although the bulk of the work has been done with large radio controlled models between 7 ft. and 7 ft. 6 in. long of various scales, it has been part of the exercise to find if models of this large size, and around the “A” Class model, can be relied upon to interpret the airflow of similar type sails in full-scale. It has been shown that they in fact do this correctly. I would suggest that there is little quite so stimulating to designers and yachtsmen as being able to “see the flow” around sails, keels and hulls. Wool tufting and smoke show up the sails, whilst streams of airbubbles, dyes. etc., can show the flow around keels and hulls in the enclosed water flow tank. It was accordingly decided to include a certain amount of corroborative full-scale sailing, and two fellow enthusiasts, John Hogg and Bob Curwen. afforded much stimulation and invaluable co-opera- tion, particularly with instrumentation, whenever opportunity permitted, whilst my wife patiently did much of the photography. The Models and Full-scale Craft Used The full-scale craft employed, with wool tufted sails. were the “X” One Design keel boat which I regularly race (20 ft. 8 in. L.O.A. with sail area 184 sq. ft.), an experimental six ton sailing cruiser, a flying Fifteen, and a wool tufted test on a leading 12 Metre yacht, the type of craft used in the America’s Cup. The model craft were an accurate 1/3rd scale model of the X Boat mentioned above, several 1/4th scale light displacement craft to my design, three 1/9th scale 12 Metre models, and two “A” Class hulls. All models were radio controlled. Where two identical hulls are required for comparative work on rigs and keels, the hulls are made in glass fibre from the same female mould, Some hulls are round bilge, some single chine, and others double chine. The large size sails, around 8 ft. in height, are made by the well known helmsman and sailmaker, 227

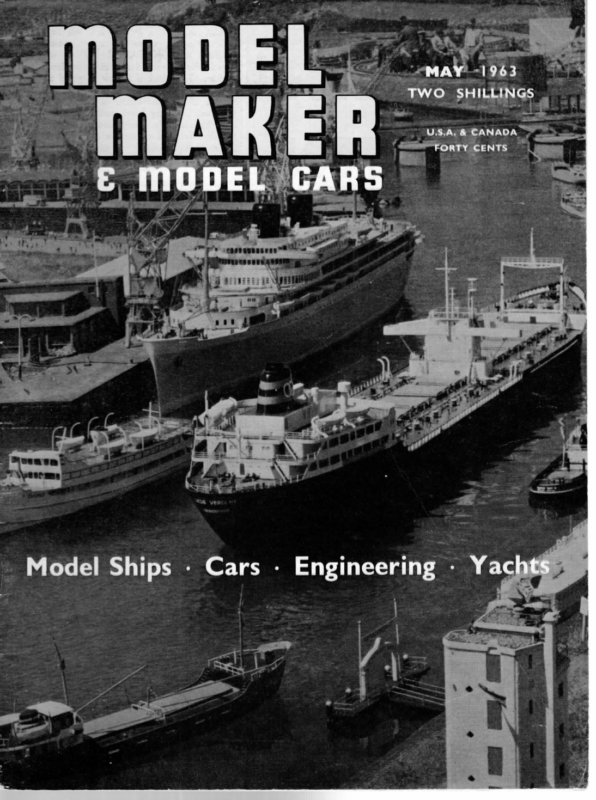

MMOUEL IMIANKIE!R} Bruce Banks, whose co-operation and sail research enthusiasm ensures the greatest personal care to produce accurate scaled down sails. Yacht Research centres have found this quite a problem, and two of the best known British sailmakers have come to the conclusion that model sails must be between 7 and 8 ft. tall for accuracy in scale reproduction. Last season I tried a successful method of checking model sail curvatures against full-scale in order to find the curvatures taken up by sails when wind pressures and stretch deform the surface in windward sailing. Some surprising facts came to light which are given later, in Part II of this article, with instructions that will enable any model yachtsman to find the curvature his sails take up when in action. Wind Tunnel Tests and Sail Test Bed, to Mate Up with Wool Tufted Tests Southampton University, with now perhaps the best equipped yacht research department in the world, last season opened a yacht towing tank named after Dr. Lamont, the well known American yachtsman, who made it financially possible. Dr. Lamont and myself have been connected for some years in experimental interest. At the same time at Southampton a large slow speed wind tunnel, capable of taking model sails of around 8 ft. tall, commenced work on sails in a general research programme sponsored by the Advisory Committee for Yacht Research, a non-profit making body. As a member of this committee, I loaned my 1/3rd scale “X” Boat model rig, 8 ft. in height, for the initial tests of a jib slotted rig. A single sail Finn rig has been tested, and a genoa rigged Dragon is about to be tested. As readers will know, research findings by a university are not kept secret, as so often must happen with commercial tanks and wind tunnels. Therefore the University have recently published a full report in book form, of the measurements made on the model X Boat rig, entitled, ““Wind Tunnel Tests of a 1/3rd Scale Model of an X One Design Yacht’s Sails—Advisory Committee for Yacht Research”, by C. A. Marchaj. This report may interest model yachtsmen for it is full of meat, and provides many useful conclusions. It is obtainable from Mr. T. Tanner, Dept. of Aeronautics, The University of Southampton, for a few shillings. Some may also like to support the further seven years’ research pro- gramme by sending a small or large donation to this worthy cause so neglected in Britain in the past. Research is an expensive business even when done for the general good, and on a non-profit making basis, as in this case. Important Wind Tunnel Findings Amongst a number of interesting findings from the “X” Boat report, measurements show that’ altering the sheeting angle of the foresail, with the mainsail fixed gives large changes in driving forces, up to 63 per cent, but relatively small changes in heeling. On the other hand, changes in trim of the mainsail af- fect heeling considerably. This is an important finding in view of the well established fact by the American Davidson Tank, that the heeling angle of a keel boat must not exceed 20 degrees if resistance is not to be increased in windward sailing. If a hull is heeled to 30 degrees, there can be as much as a 25 per cent increase in resistance. The report further points out from force measurements, that a “relatively” flat jib is required, causing the minimum of backwinding drag. The jib should then be sheeted as near parallel as practicable to the mainsail. Racing experience indicates that in a strong breeze, it is important to sheet the mainsail as “fixed’’, well outside the boat’s quarter, by hauling down hard to a very wide track fixed to the deck, in order to cut down “twist”. The boat can then be feathered up to the gusts, as in radio sailing, with well flattened main at a fine angle of attack to parry the gusts. It is, however, knowing when consciously to pull the boat off the wind a trifle, to keep her going through the water and ensure driving the hull forward against vastly increased airdrag and seas, without overheeling, that puts certain helmsmen out of the merely good class into race winners in the rough stuff. A vane can only follow the wind. It cannot compensate for changes in seas, and “apparent wind” speeds. Even radio control finds difficulties, because rudder action can cause over-control, a trifle late, until we get a really good non-linear steering. However, improvements are constantly taking place, and radio control does basically permit conscious helmsman variations from the vane’s merely following the wind gusts, which is the essence of exceptional helmsmanship. The Southampton report further mentions two points I have previously made in Model Maker. To quote: “Sail design is at least as significant as hull design on the performance of the yacht…” “A current question of great interest to English yacht designers is the rather shattering success in offshore racing of the beamy shallow draft American Centreboarders . . . these have virtually eliminated the competition of the narrow, deep keeled yacht”. (Centre-boarders are large hulls with outside ballast, but deep boards that can be let down to improve windward work, and some also let down a board aft for running). Heading photograph on previous page is Fig. 1, an A class model on a windward leg; note regular airflow compared with Fig. 2, left, where the maximum camber point of the sail shape is much closer to the mast.

MAY 1963 The reason for the report mentioning these wide shallow hulls and their success, is that they provide amongst other advantages, a wide sheeting base to improve sail drive and reduce side force and its overheeling. Personal experience of a number of experimental model hulls of the wide shallow variety, round’ bilge and double chine, has impressed me with their great possibilities, for model racing. I think there is scope for much experiment in the model field in this quarter. The exciting thing is that these craft not only offer a really wide sheeting base to get better performance from redesigned rigs, with optimum trimming for different wind strength, but such huils are far stiffer, and can sail to windward better within the 20 degrees angle of heel required. Half the hull comes out of the water, cutting wetted surface, when properly heeled, also hulls like this create very little wave making as opposed to the deep large hollow created by a narrow deep hull. I cannot recall seeing such a model hull’s lines being published in model journals for a very long time! A Model Sail Test Bed Augments the Windtunnel To assist the wool tufted model sailing tests, a large model sail testbed is available, to take any of the rigs from the radio hulls. A check can be made on windtunnel findings, in the natural open air with its gusts and turbulence. Forward and side thrust can be measured, with centre of pressure shifts, and centre of effort height at different angles of heel and attack. See Part II of this article. Airflow Patterns Show Desirable Position for the Mainsail’s Maximum “Flow” Fig. 1 shows a glassfibre “A” Class model sailing to windward under radio control. The airflow pattern disclosed by the wool tufts is regular on the windward side, because the max. “flow” of the mainsail is positioned well aft of the mast, nearly at midchord position. The usual down trend flow of all triangular sails on both sides, to a vortex at the foot, can be seen. An endplate has been found to improve this flow considerably. Full-scale patterns are exactly similar. In Fig. 2 it will be seen that the 7 ft. 6 in. L.O.A. radio controlled glassfibre boat has a mainsail specially cut, as many sails are made, with the maximum “flow” or curvature positioned well forward just behind the mast. The wool tufts show a disturbed flow nearly to the half chord of the sail. Such sails cause considerable weather helm, for the centre of pressure has moved aft in windward sailing, tending to luff the boat into the wind. The jib is then often mistakenly sheeted closer in to “balance the boat”, and good sail interaction is lost. Refer back to Fig. 1 to see a correct flow. Figs. 3 and 4 indicate the flow behind a single sail (cat rig) with no jib slot. In all cases where a conventional round or streamlined mast is fitted, the airflow is completely broken down in lee of a single sail when sailing close hauled to windward. The full-scale “X” Boat with its normal jib removed, seen in Fig. 4, is included to emphasise the very close similarity of model sail patterns to full-scale of a similar sail type, provided the model is large. Figs. 3 and 4, right, show the single sail ‘“‘cat’’ rig and the similarity of flow round the sail(s) of a large-size model and a full-size craft. Both pictures show effect of mast interference on leeward side, It will be seen that both craft have a broken down flow in lee, by the way the wool tufts are flying irregularly in all directions. To obtain good forward to side thrust, low heeling and low drag, the flow should be smooth and what is termed “attached”, in lee. : Part II of this article examines a method of obtaining “attached” flow on a single sail. It also examines Bermudian rig with jib in action, and also what happens with different length of overlapping and non-overlap headsails.