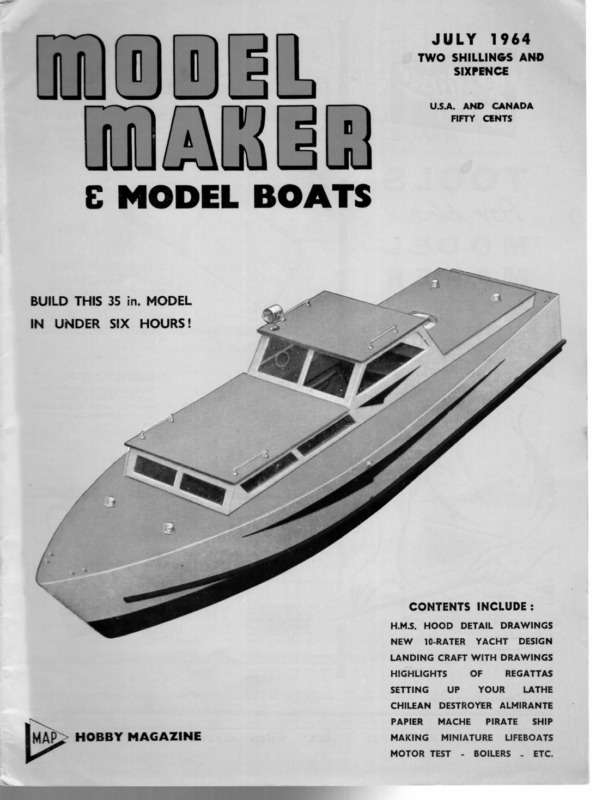

JULY 1964 TWO SHILLINGS AND SIXPENCE U.S.A. AND CANADA mn AK E i ae E MODEL BOATS BUILD THIS 35 in. MODEL IN UNDER SIX HOURS! CONTENTS INCLUDE : H.M.s. HOOD DETAIL NEW 10-RATER DRAWINGS YACHT DESIGN LANDING CRAFT WITH DRAWINGS HIGHLIGHTS SETTING MAP> HOBBY MAGAZINE OF UP CHILEAN DESTROYER PAPIER MACHE MAKING – LATHE ALMIRANTE PIRATE MINIATURE MOTOR TEST | — REGATTAS YOUR SHIP LIFEBOATS BOILERS – ETC.

HUGH TENSION A 60in. W.L. 10-Rater by Join Lewis ILST it is not difficult to design a 10 rater which looks different from the normal run of boats it is quite another thing to produce a design that is a progressive development. High Tension is a seriows attempt to exploit all the best characteristics of the Sireceo Red Herring line of boats which have proved so successful over the past eight years, plus features of the twin keeler Herald. Fundamentally it is another attempt to crack the 60 in. L.W.L. barrier which has been a challenge to me for many years. I have always looked upon 60 in. L.W.L. as the magic figure and have made several attempts to produce a satisfactory design to that length. These have not been too good as each time the long boat was designed I decided to reduce the displacement to something like 26 lb. and so, while they were quite good in medium winds, they would not stand up to heavy weather. The exception to this was Herald which showed that twin keels enhanced heavy weather performance but killed the light weather end of the scale due to the inherent high drag of two keels at low speeds. This time I have taken Sirocco/Red Herring type as the basis of the design and have, with minor detail modifications, stretched the canoe body out from 55.0 L.W.L. to 60.0 L.W.L. The-beam has remained the same but the ends have been slightly filled out above the waterline to increase the heeled length and the freeboard increased to improve the general appearance. This should result in a hull with considerably greater potential top speed but of course the wetted surface has gone up and will tend to retard the boat in light airs. It is difficult to calculate the exact actual increase and even more difficult to assess its actual effect as the increase in area forward of amidships will be less detrimental than that aft of midships if laminar flow can be induced at lower HIGH TENSION DesioneD OF SERVICE aa° i : i “| ry } 8 z : ry 3 8 2285 EATS | WATFORD. % PLANS AD. § 38, CLANENDOM g MODEL MAKER ar Lewis comymicnt i John A.

JULY speeds by virtue of a superb finish to the hull. This incalculable penalty is accepted as I never feel it is worthwhile getting too worried about very light air performance because model yachts spend a lot of time going in the wrong direction in those conditions, anyway. Now let us take a good look at the keel. Is there any point in carrying wood in the keel behind the lead? In my previous designs this wood has provided 1.4 lb. of positive buoyancy just where it is doing no good at all to stability and is only providing some displacement which otherwise would have to be carried in the canoe body. By virtue of the increased length of the hull this displacement, plus some more, is automatically absorbed without coarsening lines. In fact, the lines are finer. Here we suffer no penalty by the development. The keel has therefore been designed to contain the required amount of lead, which is greater than the Sirocco designs, and to be of an efficient shape hydrodynamically. The temptation to use plate or bulb has been resisted as I’ve yet to be convinced that it has real virtue, and a higher centre of gravity of the lead ballast is accepted in this case. The interesting thing is that calculations show that although the C.G. of lead in High Tension is 0.85 in. higher than Sirocco the actual pendulum moment effect is exactly the same due to the extra weight and the elimination of the deadwood buoyancy. Therefore the new keel has not reduced the stability of the design and we know that Sirocco’s sail carryIf anything, High ing power is quite adequate. Tension will be more powerful due to greater length 1964 on L.W.L. and the extra displacement will give her greater inertia to overcome the seas in heavy going. An incidental benefit from the new shape is that 10 sq. in. of wetted surface has been saved. The skeg and rudder has not been pushed out to the extreme L.W.L. ending as too long a moment arm could cause her to be slow guying in light airs. This is a favourite way of losing races. In drawing the lines I have departed from my usual layout and it will be seen that the waterlines are spaced # in. apart instead of the usual 1.0 in. and there are more buttock lines than usual in my drawings. There is also a full set of diagonals and all this goes to ensure a particularly good fairness in the lines. The centre of buoyancy has moved slightly and is now midships, a change which is due to the difference in the new keel shape, and the hull lines are slightly finer aft of midships than forward_but fuller right aft than compared with the entry. Thus the hull has some ‘codshead’ tendency which helps reduce low speed resistance but it also retains enough power right aft to produce high maximum speeds. Naturally the balance of the hull is almost perfect as I think there is little justification in following the latest fashion in full-size design and having a very fine entry and full stern. The pendulum of fashion is swinging again in large craft but the swing is for reasons not applicable to model design and I see no good reason to depart from shapes which have been evolved over some years of careful study and which have proved eminently suitable for model racing craft. If we can accept that the hull of High Tension is a satisfactory step forward from my previous designs then we must look carefully at the sail plan and see what can be done to recover the lost area due to the increase in waterline length. Firstly the 10 rater rule places no restriction in deck camber and this is quite a good way of reduc- ing the fore triangle height measurement. Therefore NLE WX = ORAS : “nine the design shows a very high camber on the fore- to imitate deck planking. It is not easy to construct but that should not deter the builder who is determined to get the maximum performance from his vacht. The notch in the fore deck is shown so that a normal type of jib horse can be used and so that the jib boom can pass close to the crown of the deck and make the most use of the fore triangle method of measurement. tS A normal sail plan for a 55 in. L.W.L. 10 rater Sm RE LO a 88 38 O68 e689 deck with a reverse camber aft of the mast. This arrangement worked out very well in Herald and is extremely eyeable particularly if no attempt is made produces the following figures: Fore triangle 60in. x 16in. Less 15% = eet sq. in. 2 12 408 measured Main sail 71.75 x 19 = 681.6 sq. in. Total measured = 1,089.6 sa. in. Area allowed by rule = 1,090.0 sq. in. The free areas bounded by curved edges are: Jib Main 37 sq. in. 136 sq. in. ; The actual area of jib = 37 + 376 = 413 Ss. in. | Therefore the total actual sail area = 1,230.6 sq. in. Now. if we have a high aspect ratio sail plan as suggested on the plan and suitable for a measured total of 1.000 we can take advantage of the relatively longer leach on the mainsail and grab a few square [Continued on page 337] 329 im

t | S A simple and form effective of RUDIMENTARY RUDDER CONTROL by P. A. HODGES As first built, I gave her Braine steering, the tiller being linked to the mainsail in the usual way, but this, although satisfactory in theory, proved unsuitable in practice, since in the first place the mainsail, being comparatively small, exerted insufficient force on the steering gear, and in the second, the mizzen tended to throw the stern downwind and cause the vessel to “luff-up” into the wind. The inadequacy of the aggravated by the fact that short, and consequently of it had to be accommodated and the mizzen mast. OME months ago when I was about to build my son a model sailing vessel for his birthday, it occurred to me that all one ever saw sailing on our local boating lake were sloop-rigged Bermudan yachts, ranging in size from the diminutive shopbought toy,to the splendi i Is belongi bs.mentees of Regtarauyte The shop-bought variety were Observing meee adequate in models, although very their magnificent fitted” mizzen and the stern, mizzen I decided, therefore, to build something different. due course produced Mimsy, a gaff vessels which a violent effect topsail was discarded and the Mark to which the mizzen sheet was attached. on the outrigger — and thus the rudder — | Counteracted the tendency for the model to run up rigged into ketch of my own design, based on the several types of similarly rigged fishing populated Southern waters. had This was reasonably effective, for the pull of the me to be simply racing machines. in mizzen 2 Steering gear was evolved. This consisted of an OUtrigger attached to the tiller, and projecting over capable of sailing af astonishing speeds, seemed to and the si upon the sailing qualities of the model, the “as first way, and all (or nearly all!) sailed quite well on some indeterminate course or other, while the large racing that im steering gear was also the tiller was necessarily poor lever length, since between the rudder post the wind. She would beat and reach quite Well, but running still presented a problem. once The outrigger can be seen in the photo opposite and Fig. 1 should make it clear how the gear She is 264 in. long overall, 17 in. at the waterline, worked. Adjustment of the rudder operation could has a maximum beam of 4% in., and a mean draught _ be achieved both by altering the “bowsie” to which of 4 in. The hull is pine conventionally built breadthe mizzen sheet was attached, and by an adjustment and-butter fashion, the deck is mahogany, the bul- of the rubber-band tensioner. warks aluminium and the keel cast lead. MIZZEN MIZZEN BOWSIE SHEET TILLER Incidentally, these photographs show Mimsy set- MAST RusBER BAND ting a @ later date || headed’ jackyard this topsail was topsail. on replaced when a the by main a topmast mast. At conventional was fitted to a ‘jib- the mainmast. 2 All this time I was. of course, aware of the i efficiency of vane steering, but was confounded by the wretched mizzen mast, until it occurred to me that I might very well be able to effect vane steering by means of a flag-like vane mounted at the mizzen mast head. Using the existing slotted tiller, the Mark 3 gear took only a couple of hours to complete and_ is astonishingly efficient despite its simplicity. It has, of course, none of the refinements of the true vane steering devices, but enables the model to be set to 340

JULY VANE SHAFT VANE SHAFT A AND LINK FROM necessary course correction. Fig. 3d, shows relative vane positions for beating (starboard tack) (i) and running (ii). ~ ¥3o BRASS WIRE TILLER FROM “a BRASS It should be pointed out here that the examples shown in Fig. 3 do not take MIZZEN MAST HEAD BRASS WASHER VA TO (SOLDERED poieiee 6 Oe ane BRASS ae SCREW-EYE Sine 1964 | CARD VANE : SECURED TO SLEEVE f into account the movement of the vane caused by the model’s ; motionns through the atmosphere. In Fig. D (ii) — the rtant ition—this isi nottiimportan running g condition—this \ ADHESIVE] © PROOF since the model will not travel at a greater velocity than that of the wind, VANE BALANCE ( Bon nee ate TH PUSH-FIT SLEEVE and thus, the vane will always tend to maintain its fore and aft position. In the beating and reaching condition, however, the faster the model moves the greater will be the ‘“‘windage” on the vane, tending to move it further aft, so that the vessel will “pay off” and sail less close to the wind. Eventually, it can be seen that a state of equilibrium beat, reach or run with equal facility, which is all that is required of a model intended to be reasonably practical — and indeed “boy-proof’ — rather than exactly predictable. The heading picture shows the vane (painted with matt oil colours to represent the Red Ensign) and Fig. 2 shows the detail of the gear. The vane balance weight was fitted to counteract the preponderance of the vane, for with the vane set to beat, its own weight tended to give a false rudder correction when the model heeled. For those familiar with vane steering, its operation will be obvious, but for those ash are not, the following may help to make it clear. Movement of the vane, which is frictionally held on the vane-shaft, directly controls the rudder through the slotted tiller, but in an_ opposite direction to its own movement. Thus, if the vane-shaft moves clockwise, the rudder shaft moves anti-clockwise. In the example given in Fig. 3a, the vane has been set at right angles to the rudder to allow the model to “reach”, i.e., to sail with the wind abeam. The wind direction is assumed to be constant throughout the sequence. In Fig. 3b, the. vessel in an antihas come up into the wind, resulting. clockwise movement of the steering vane, and a consequent rudder correction. In Fig. 3c, the vessel has “paid off”, causing the vane to move clockwise and the rudder anti-clockwise, again providing the i TRUE t e COURSE will result, when under constant wind conditions a steady course will be maintained, but in any case, by experiment, a “windage” correction can be applied to the initial vane setting. Pd Ze T e ° ce Di A CONSTANT WIND c <—_,; VANE TILLER \ D2 RUOOER VANE LINK FIG.3 pa Ree a Las) — 341 | No doubt the purists of the model yacht racing fraternity will laugh their heads off at this rudimentary device, but nevertheless I feel that the run-of-themill model maker like myself may well find it a worthwhile and simple extra to a model sailing vessel, for I see no reason why this device should not be fitted to a single masted yacht, provided the tiller and vane-link are designed with reasonable care. One final word—Mimsy normally sails with Flag D of the International Code Those flying from the crosstrees. familiar with the International Code of Signals will know that Flag D means: “Keep clear of me I am manoeuvring with difficulty”!

MG) D)E IMVA\KIE!R) PETREL 18 in. bread and butter sailing model cruiser from last month’s full- size plans. PART TWO. UITE a number of readers have had their fancy remember though, that molten lead is dangerous if it flies about, and that it will burn the floor if spilled! First mark the lead line accurately on the hull, both sides, and carefully saw away on the lines with a fine saw. The piece of wood cut away forms the caught by this little model (little?—like all boats it comes out bigger in fact than the impression the drawings give) and we shall therefore be a little more expansive in its coverage, running to three articles instead of two, which gives us a chance to go more fully into some of the constructional points. pattern to which the lead must be cast. One query we have received in respect of the basic hull is how does one get a 5; in. wide hull out of 4 in. wide sheets? As mentioned, each plank is in two halves above waterline F, and the widest timber strictly needed is therefore half of 5, in. However, if such a plank is laid out on the edge of a 4 in. wide sheet of balsa, there is room to repeat the shape above the first one laid out; by juggling the halfplanks and narrower full planks in this way, it is not difficult to cut all the planks from the two sheets of 2 X 4 x 36 in. balsa specified last month, with minimum waste. Ours came out of two sheets (Fig. 1). Rub the wooden pattern to a smooth finish and give it two or three coats of wax polish (floor polish, etc.) to prevent plaster sticking to it. Place it in the box and slip a couple of pins into it to prevent it moving (Fig. la). Now mix about two- thirds of a cup of plaster of paris or, preferably, dental plaster — two or three penn’orth from the chemist. We used, as an experiment, Polyfilla, and this works quite well though is a little coarse for a clean cast. The plaster must be mixed to a consistency of something like thick paint or thin condensed milk, so that it will run reasonably into all quite easily. As also mentioned, the half-planks are cemented together and allowed to dry before assembling the hull into a block. The photographs of the hull blocked together show the importance of marking the station lines on all faces of the planks; it can be seen how easy it is to align the planks correctly. Perhaps the biggest job, after carving and sanding the hull to shape, is casting the lead, but don’t be put off by this—it really is quite simple and well within the capabilities of the average modeller, Just Make up a box of & in. balsa (or ply) large enough to contain it corners but not be so wet as to refuse to set hard. Pour it into the mould box till it is filled, tapping the box bottom on the bench fairly sharply to ensure that all air bubbles are cleared. Leave to set, then cement the “lid” on the box. Turn the box over and remove the pins; carefully cut away the box bottom on the original joint line (Fig. 1b). It may be necessary to insert a small screw in the pattern to give a grip against the tendency of the pattern to stick. Ease the pattern gently out, bow end first, and you should have a nice smooth mould. Any big pits may be filled, but small ones can be left if you don’t mind the mould being damaged when the finished casting is extracted. There are two ways of casting open to us, with a flat-topped casting such as we wish to make. One is simply to pour the lead in the open-topped mould (Fig. Ic) until it is filled; this means that the mould will be over-filled since lead has quite strong surface tension and a meniscus will be formed, so that to fill the mould up to the edges the centre of the lead will be about & in. higher. This excess can easily be sawn or filed off, and at least you can see what you’re doing. The other method is to replace the box bottom after making a filler hole and a breather hole at each end (Fig. 1d). In this method you pour lead into the filler hole until it runs out of the breather holes, which means you have only to cut off the spues where the lead has filled the holes. We used the former method. It is most important that before casting the mould is bone dry—any moisture in the plaster will turn into steam and may blow the lead up into the air. The mould should thus be baked thoroughly before 350

JULY 1964 Heading picture shows the model taken to the stage dealt with in this instalment. Bottom left, are exterior and interior views of the blocked-up hull—always rather a frightening sight! Half an hour with a knife, rasp and glasspaper works wonders, Below, the improvised oven used for baking the mould. This precaution Bottom right shows the completion of is once again stressed. pouring, Note rag wrapped round hand in case any lead should spit. In fact it was like putting milk in a teacup. use. The lady of the house may not fancy it going into her oven, and if it’s a gas oven it’s not a good idea anyway. We slipped the mould into a large tin and rigged up a device over a Bunsen burner, hanging the tin lid on the end to conserve heat but allow steam, etc., to escape. This step is vital to avoid possible injury, not to mention a spoiled casting! For lead, most plumbers’ merchants stock lead wool, allegedly in 1 lb. balls but in fact usually well over this. One ball should do—the actual cast weight, including meniscus later cut off, is just under 18 ozs. Old lead sheet or pipe can of course be used, but if you haven’t a local scrapyard, lead wool (2/- a ball) is excellent, especially as it is simple to melt. An old saucepan, preferably with a lip, is excellent for a melting pot, or a large old ladle, glue pot centre, etc., will do. You should get enough heat quite easily from a gas ring or by lowering the pot into a solid fuel boiler or brewing on an open fire, either indoors or built between some bricks in the garden. We used the Bunsen, which was not quite enough, so a paraffin blowlamp was used for an extra source of heat. As a precaution, we wrapped a rag round the pouring hand. When melted, the impurities in the lead will float to the top, but on pouring clean lead will flow from beneath this “crust”. Pour smoothly and steadily into the mould until filled; don’t be surprised if, as the heat works through, the cement joints in the box flash into brief flame. The heat may scorch the balsa, but the mould or box is unlikely to fall apart or go up in flames. FILL WITH DOWEL We wired two lengths of 4 B.A. studding in place on the mould before casting, so that the finished lead held these firmly and, when poked through two accurately drilled holes in the wood keel, they secured the lead in place. Having these made cleaning up the top of the lead more difficult, and a better idea for a lead of this size is to drill it to accept two 4 B.A. bolts, drilling a clearance for the heads, and tapping in a piece of dowel after tightening the bolts (Fig. 2). This method means that the top can be planed (yes, with an ordinary plane, if you wipe it with turps). The finished weight of the lead when bolted on should be about 14 0z., which allows a small margin to adjust the trim of the complete model by drilling one or two holes and tapping in dowels. If the top 351 I

MONEL IMIANKIEIR Rigl.t, the hull with finished cast lead, mould box and wooden pattern. The overflow of thin plaster can be seen on the box side, and also scorch marks from casting. Another view of the hull, mould box and pattern is shown in the photograph below, while at the bottom is a view of the hull after attaching the lead and fitting deck beams and carlings. Photograph on opposite page shows the completed cockpit, etc, ready for the fitting of the deck, followed by the dummy forward cabin. Note reinforcement post and heavier deck beam at mast position. Butt joins between deck and cockpit front and rear are adequate but additional light fillet strips can be used if wished. is reduced a little more than expected, a slip of in. sheet, etc., can be cemented to the hull so that the bottom line meets nicely. 12 S.W.G. 16 S.W.G. Before tightening the bolts, smear a little epoxy or polyester resin or thick paint on the seating surfaces, then tighten up. Use washers or a slip of +; in. ply under the nuts. Leave to dry. The rudder is the next job. This is cut from 3 in. sheet balsa and sanded to the section shown. The TUBE fore edge is grooved to take a 6 in. length of 16 s.w.g. brass tube, which is held into the groove by TUBE cementing and covering with a patch of fine nylon or RUDDER SECTION BRASS PIN silk the full depth of the rudder and about 2 in. wide. Le cement well into the pores of the nylon or silk. Groove the after face of the keel and drill through the hull. Slide the rudder in place and check for a smooth fit and clearance. Enlarge the hole through the hull to accept a 1% in. length of 12 s.w.g. brass tube—standard 16 g. tube fits nicely inside this. Cement the 12 g. tube in the hull, leaving the rudder in place to make sure the angle is correct (Fig. 3). Later, the lower pintle will be fitted to hold the rudder in place, but in the meantime the rudder is removed and finished and painted at the same time as, but separately from, the hull. The use of 16 g. brass tube simplifies fitting the pintle; it costs only coppers and is usually more easily available than brass wire. There will be a slight tendency for the rudder to jam itself when afloat, since its natural buoyancy will cause it to rise in the 12 g. tube; a little care at the top end will minimise this effect, which is not really very important with this type of model in any event. Deck beams were mentioned last month, and the only addition to these is a vertical strut of 34 in. square beneath the mast deck-beam. The mast can of course be stepped through the deck down .inside the hull if required, and this may be advisable if the model is to be entrusted to the care of a younger 352

JULY 1964 enthusiast. Ours is stepped on the deck, which allows adjustment should it be needed. The interior of the hull should now be varnished or painted a couple of coats to prevent water absorption should any find its way in. Mark points on the deck beams as in Fig. 4 and cement in place four pieces (carlings) of & x 2 in. balsa. The cabin is dummy on our prototype, but the cockpit must obviously be sunk. Cut two cockpit sides (full-size drawings given here) and cement to the insides of the after carlings, checking the position from last month’s plan. The rear cabin bulkhead fits between these at the fore end (check your dimensions beforehand in case you're a fraction wider) and a rectangle of 7 in. sheet forms the cockpit rear. All these pieces can be balsa or ply. Fit the step in the cockpit, then the two floors; fit these carefully as water in the cockpit must not leak into the hull. The deck can now be fitted, butting up against the cockpit structure and positioning the head of the rudder tube so that it is not moved out of alignment. Use ay in. ply or +4 in. balsa for the deck ; if you’re keen, paint or dope the underside first, before secur- ing in place, but do not paint areas which will be in contact with glue. Protecting the underside will increase the life-span of the model and its finish considerably. When dry, sand over the deck and cut the cabin sides and front. Mark the positions for these pieces —_—- and cement in place. Paint inside, then add the coach-house roof, once again either sy in. ply or 75 in. balsa. At some stage—certainly after attaching the lead —make a stand for the model. That in the photographs is simply cut from 2 in. balsa, one vertical piece gusseted to a floor. It holds the yacht firmly, prevents it being inadvertently marked, and makes working on it a great deal easier. Eee Moe Pol [To be continued] "CABIN REAR 1/8"—___ | —DECK LINE oe COCKPIT SIDES —— pe LN A tal 13 SOCK PIT —— REAR, FLOORS, ———— le SO ABIN SIDES TA 68! —— —— — ___ ee, 353 FIC. . 1/716"