Text and photos by Bob Jones

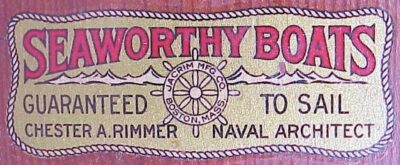

Collectors have been buying and selling toy boats and sailboats for many years with the label

Seaworthy Boats

Guaranteed to sail

Chester Rimmer Naval Architect

Later boats were marked “Jacrim Manufacturing”, “Hollow Boat”, and then “Keystone Manufacturing”. Their products were sailboats, toy motorboats (with wind-up, rubber band, or electric battery motors), Tom Thumb toys, Ride‘Em toys, forts, and toy furniture. The Seaworthy Boats are the most sought after toy boats for collectors of all the other toys on the market—from Chein’s “Peggy” series tin boats, Rich Sailboats, Starr and Bowman (sailing yachts from England), Lionel, Lindstrom, Mengle motorboats, Kingsbury boats, and many other lesser known manufacturers. These production boats differed from the home-built pond boats built by fathers and sons in the thousands.

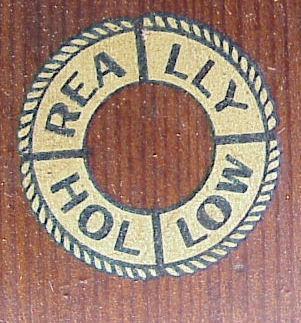

These manufactured pond boats were designed by an MIT-trained naval architect. They really would sail. They looked good, floated on their waterlines, were inexpensive by today’s standards, and were all handmade. The 28-in “Really Hollow” raised deck sloop cost $6.00 in the late 1920s. Shortly thereafter, Seaworthy Boats Jacrim Manufacturing was acquired by Keystone Manufacturing, and all of the products were machine-factory crafted and were very well made. By 1950, a 22-in Keystone sloop cost $25.00 per dozen wholesale.

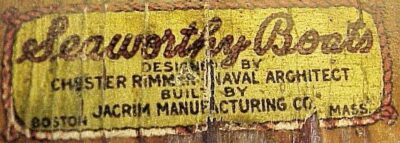

A corporate record search in Malden and Boston, MA, found no record of Seaworthy Boats. Seaworthy Boats was not Chester Rimmer’s first company but was a trade name of boats manufactured by Jacrim Manufacturing Company. The yellow Seaworthy Boats label is from an early boat and confirms that fact. In 1921, the first official record for Jacrim Manufacturing was found in the Boston business directory. The Iron Trade Review, August 3, 1922, listed the incorporation of Jacrim with Charles H. Jackson as president. Arthur Jackson’s father, Charles, provided $10,000.00 to start the company. In 1924 the Boston directory listed the officers of Jacrim Manufacturing as Chester Rimmer and his brothers. The Boston City Directory of 1925 lists Jacrim Manufacturing in Maldin, MA. Arthur Jackson is not mentioned in any official papers concerning the company. He was a college friend who shared the dream of toy manufacturing. There weren’t many jobs or offers of work in 1921, so Jackson and Rimmer formed their own company, and Jacrim was born. Arthur was the “JAC” in “JACRIM”, and Chester Rimmer was the “RIM”. All the documents I have collected show the name as “Jacrim” not “Jac-Rim” as is quoted by many.

Chester’s father, Joseph Rimmer, was born in England in January of 1858, and he grew up helping his father do carpentry at the family church. Deciding there was no future in England, he set sail from Liverpool to America on the Samia in September 1880. He was listed as a wheelwright, cooper, and cabinet maker. He settled in Malden, MA and built a house at 62 Belmont Street. He had three sons: David W., John Wilfred, and Chester. Chester and his brothers all lived there during the early days of Seaworthy Boats and Jacrim Manufacturing.

Chester was described as tall, with a medium build, gray eyes, and brown hair. He registered for World War I in September 1918 and became a shipfitter. Not much else is known about him, but he attended Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) where he took courses in marine engineering. While at MIT he wrote a thesis with E.I. Howard and A.L. (Arthur Lawrence) Jackson, titled “Aluminum Alloys in Ship Construction”. In June of 1921 he graduated from MIT with a Bachelor of Science: Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering.

Arthur Jackson was his college friend from Melrose, MA. His World War I draft registration card listed his occupation as a student at MIT. Jackson’s father was Charles H. Jackson, and his mother was Kate A. Jackson. He graduated from MIT at the same time as Rimmer with the same degree. The 1924 Melrose City directory listed Arthur Jackson as a marine engineer. The photo at left is Jackson in 1929, after he had left Jacrim. (It is not surprising that Jackson left the company, because Chester was a difficult man concerned with his own interests. This became apparent later when Keystone took over the company, and Chester did little to protect his brothers.)

There are no corporate papers or information on what happened next. I suspect that when they got serious about the company manufacturing toy boats, they rented space upstairs on Cross Street & Main Street, in Malden, MA. The older Rimmer brothers must have provided the money because Chester and Arthur were college students. Older brothers (David and John) were listed as the officers, and Chester was treasurer with no mention of Jackson.

David Rimmer was a pattern maker, and John was a cabinet maker, so they all had woodworking skills. There is no official record of Seaworthy Boats in state or town records, and it appears that it was a trade name for Jacrim Manufacturing.

The Cross and Main Street wood shop in Malden was on the second floor and the original building is still there. All the boys (Chester, David, and John and probably Arthur Jackson) worked there. Charles Jackson (Arthur’s father) was listed as the early president, so he had to have frequented the location. As was the custom in 1924, they worked six days a week. According to David Rimmer, Chester’s grand nephew, many nights after dinner his grandfather, Chester and his brother John walked back to the shop from their house and continued working. The house was about a 15-minute walk. In the 1920s there was no TV or radio, so there was not much else to do. They all were actively working in the wood shop and, in fact, David lost two fingers during that time cutting products. Early pictures of Seaworthy boats show that some of the first boats made were quite detailed and one-of-a-kind. This is what you would expect with a pattern maker, a cabinet maker, and two engineers building and designing the boats. They probably started building boats about 1921, either while in college or directly thereafter. An early primitive boat I have seen had a cast brass plate. Other early boats sported bowsprits. The main production seems to have started in 1924 and carried these labels.

The early boats had solid wood hulls with the “Hollow Boat” label coming later.

Some sailboats marked with the “Seaworthy Boats” label and showing nice details have been showing up at auction houses. These are gaff-rigged boats with bowsprits and intricate sails and fittings. These boats look fine and show age, but they were not produced by Seaworthy. Only the hulls were original. These boats were rebuilt in the 1990s to look old and sell. They are attractive and very well done. Probably they were produced by a Boston ship model company to look old and original.

Arthur Jackson is not mentioned in any articles or documents, nor is his name known to the surviving family. He left Jacrim in the late 1920s, probably in 1926, and was shown in a 1929 photo in the American Enka Voice with a group of new hires that year. At Enka (the US’s largest rayon manufacturer) he originally oversaw the drafting section and then worked for several years in the research department. This was in Asheville, NC, where he became the Enka Plant Chief Engineer. In 1955 he was named Director of Engineering, and later in 1959 he was honored for 30 years of service in Asheville. At Jacrim, Chester designed the hulls, the brothers did the woodwork, and I believe Arthur oversaw the mechanical aspects of the rig and procurement of the supplies. Once this was done, there was not much need for him. Jackson may have been the designer of the spring-assisted automatic rudder. The sail rig, rudder assembly, and keel did not change much for the entire life of the Jacrim boats. The spade keel on sailboats changed to its final shape around 1932, and the rudder shape changed to a teardrop shape that probably saved material over the early barn-door shape. The Flying Yankee motorboats used an intricate spring coupling to drive the propellers and had a string pulley system for the rudder. I think this was more of Jackson’s work. By the late 1920s, business was probably poor. Arthur did not see any room for him in this family business and elected to move on. He may not have been a skilled woodworker, but he was a good engineer. This was proven by his 30 years service at American Enka. No one at Enka or the surviving company knows anything about him or where he lived or died. However, between 1938 and 1944, he is listed as the inventor on numerous patents for spindles and bobbins that were all assigned to American Enka. He certainly was a fine engineer and was earning more money than the toy business could have provided. Probably the opportunities at Seaworthy Jacrim did not challenge him as an engineer.

It should be noted that in the beginning these boats were not toys to Chester. According to David Rimmer (Chester’s grand nephew), none of these boats were available to him as a child—even though his family had been involved in the business. He remembers visiting Chester’s home and not seeing any of the Seaworthy products. This is unbelievable as these were toys boys would kill for. He was told “DO NOT TOUCH ANYTHING”. This again shows the hard side of Chester. The family had a summer home on Lake Winnipesaukee, but no boats were available for the boys to sail.

Keystone Manufacturing began as the Marks Brothers Company about 1911. Marks Brothers made human hair doll wigs and celluloid doll heads. Soon they also offered steel toys, trucks, airplanes, construction toys, trains, and water-squirting fire trucks. The 1926 Boston City directory states that Jacrim moved from Maldin to Boston. Isadore Marks was president of Marks Brothers Company at the same address. Benjamin Marks was listed as treasurer of Marks Brothers Company as well as secretary of Jacrim Manufacturing. Chester Rimmer was still treasurer, but his brothers were no longer officers of the company and soon after lost their jobs.

The Marks were a family of Russian immigrants who came to America about 1895. In 1921 they lived in Boston. Isidore was born in 1887, Benjamin in 1896, Joseph in 1882, Rose in 1894, and Rebecca in 1890. The 1810 census showed Joseph, the oldest brother, as a house painter, Rose as a ladies haberdasher, Isidore as a gas fitter, and Rebecca as a stitcher of neckwear. By 1915, Marks Brothers was incorporated. The 1926 Boston City Directory listed the Joseph Marks Company at 2176 Washington Street, rear, Roxbury, MA; the Marks & Knoring Company at 40 Winchester St.; and the Moss & Marks Company at 101 Albany Street, Boston.

By 1919 these companies and people were integrated into the Marks Brothers Company at the 40 Winchester Street address. This family came to America as immigrants at the turn of the century, saved their money, and set up manufacturing of toys and other products. They acquired other small companies for growth. Edward Swartz started Keystone Manufacturing in 1919 with $93,000; Isidore Marks was secretary. In 1922 Isidore was listed as secretary of Keystone Manufacturing Company at 53 Wareham Street, Boston. By 1925 both Keystone and The Marks Company were listed at the same address at 288 A Street. Jacrim had moved to Boston, and by 1930 was also at 288 A Street, Boston.

David Rimmer (Chester’s grand nephew) remembers that a Mr. Marks (Isidore Marks) visited Jacrim in the late 1920s just before Keystone took completely over and his grandfather, David W. Rimmer, and his brother lost their jobs. David was a pattern maker, which explains the fine workmanship that went into the early boats. David W. Rimmer went on to another Marks Company, Dover Film, and was quite successful. He also remembers his grandfather bringing home painted wooden blocks, some with windows that he used to build walls and forts. John Wilfred (Will) Rimmer also lost his job at that time and went into the railroad business and was also quite successful.

Not everyone in the Rimmer family was happy about the takeover. There was anger that Chester did not do enough to help his brothers, considering their woodworking skills. He got his dream and boat designs off to a fabulous start. When John Wilfred died, Chester came forward at the funeral with a check. His widow refused it, saying it was too late. There had been little contact with his brothers before that. Today we give all of the credit to Chester, but the brothers and their skills probably made just as significant of a contribution. We will never know Arthur Jackson’s contribution, but he probably is the one who designed the automatic steering in sailboats and the spring motor mechanisms in the Flying Yankee motorboats. These motorboat drives were quite intricate with a spring coupling, brake for off/on operation, and a string-belted steering wheel system.

After Keystone acquired Jacrim sometime in 1928 or so, they formed the Jacrim Wood division of Keystone Manufacturing. Keystone listed Jacrim as a small Boston manufacturing company making quality wooden toy wagons, boats cars, trucks, forts, and similar toys. The business relationship between Keystone and Jacrim may have begun as early as 1922, but there is no hard record of that. Keystone used the Jacrim name through 1934–1936 and then changed everything to Keystone.

This address was listed on an advertisement dated 1929 stating America’s prettiest line SEAWORTHY SAILBOATS. This move was to consolidate the Mark’s control as they were growing and needed more space. A Playthings advertisement stated “Jacrim’s SEAWORTHY SAILBOATS and the Jacrim Fleet consisting of Seaworthy sailboats, Victory sailboats, Flying Yankee motorboats and Tom Thumb toy boats”. It also mentioned a soldier fort called “Hot Shots” by Jacrim Manufacturing Company. This fort was 20 ½ by 16 by 11 inches with wood panels, solid wood columns, three siege guns, one rolling shooting gun with pellets, one defense gun, and seven flag poles. Two of the flag poles contained a raising and lowering feature for pennants. It was finished in simulated gray stone with a green base, red roof, and a draw bridge. The selling price was $5.00. It also listed various wooden horses and wagons, as well as the Jacrim fleet. The Ride‘Em toys were originally made for and named by JCPenny.

A 1932 Playthings advertisement listed Jacrim Manufacturing’s “Sensational New Line of 50 Models” – new sailboats, new powerboats, new accessory boats, and new novelty boats. The battery boat and the rubber band-powered boat were probably added to the line about then. The patent for the rubber band boat is dated February 3, 1931. By February 1, 1934 Keystone manufacturing had acquired Jacrim and named it the Jacrim Wood Division. That lasted only for a few years, and in 1937 the Jacrim name had disappeared. Keystone continued acquiring small toy companies, and in about 1940 acquired the tools and dies of Kingsbury Toy Company, who went out of the toy business.

Playthings magazine stated that Isidore died in 1951, Benjamin in 1956, and Chester in 1984.

Many Seaworthy boats were “Really Hollow” and were made with a deck and eye hooks with copper washers and small brass grommets on the sails. A drill press and gouges were used to hollow out the early hulls. Later boats used more modern means. The rigging lines were made with common string that was fastened to the hook eyes. Many used small iron bowsies to adjust the line tension. Tapered dowels were used for masts and booms with plain cotton sails. The hulls were all marked “Guaranteed to Sail”, and they did! These boats were all designed by Chester Rimmer; and as a tribute to his design, they really sailed, sat on their waterlines, looked good, and have lasted for some over 100 years.

1929 was a turbulent time in the United States because the stock market suffered huge losses. By June of 1930, the stock market was 20% of its 1929 value. Unemployment was at 25%, 100,000 businesses had folded, and 6,000 banks had failed. The period from 1924 to 1929 had been boom times, and Jackson may have seen it coming to an end. The boys at Jacrim were lucky to have already sold out to Keystone.

An interesting point is that J. Chein & Co. of New Jersey, a maker of stamped tin lithograph toys, had one of its most profitable years in 1932 according to Alan Jaffe in his book J. Chein & Co. A Collectors Guide.

Because of Jacrim’s previous profitable years, the company announced in January of 1929 the new White Cap 30-in sailboat, the new line of wooden “Tom Thumb Toys”, and the Flying Yankee motorboats. These were all listed at 1928 prices! The White Cap was a total departure from the standard steel keel boats Seaworthy had been producing. The down economy started to hit Jacrim and the White Cap 30 was not seen again. Their advertisement listed a display room at the Hotel Breslin during the New York Toy Fair. I think they had high hopes because the 1931 listing in Playthings magazine listed a New York showroom at 200 Fifth Avenue. The showroom at this address was continued by Keystone for many years. The Playthings advertisement listed the Jacrim fleet of Seaworthy sailboats, Victory sailboats, Flying Yankee motorboats, and Tom Thumb toy boats. The ad shows 20 sailboats, six Flying Yankee wind-up motorboats, one outboard or rubber band boat, and two Tom Thumb boats. This is an interesting list because I believe Chester considered the “Tom Thumb” boats toys and the other boats to be serious models. He also received a patent on a rubber band and outboard powered boat in 1931. This is the only patent found to be issued to Chester or to anyone else with the company.

There has been some mention of the Victory line of boats. Little is known about any of them; however, I have discovered an interesting fact. In 1916 Edward Joslin, the son of Kingsbury Corporation’s owner J.T. Joslin, also received a mechanical engineering degree from MIT. His younger brother was named Chester. Kingsbury’s toys included boats, cars, airplanes, trucks, submarines, and blimps. This company evolved from the Wilkins Toy Company that was purchased in 1894 by Harry T. Joslin. Then in 1918, the Wilkins name was changed to Kingsbury Manufacturing shortly after Edward joined the company. They made toys with wind-up motors. The clock-spring motor that powered the wind-up toys was introduced in 1902 and was used for the lifetime of the company. Harry’s younger son, Chester Joslin, went on to work on the toy side of the business. By 1944 the toy business, tools, and inventory were sold to Keystone, where Chester Rimmer was now a vice president.

Jacrim’s product line included the Seaworthy boats hollow sailboats guaranteed to sail, Flying Yankee spring-wound motorboats, battery-powered motorboats, Tom Thumb boats, wagons, forts, and various Ride‘Em toys.

Prior to Keystones take over, Jacrim shipped their boats in unmarked corrugated cardboard boxes. Several of the boxes for the motorboats have survived. One plain corrugated cardboard box for a 23-in Flying Yankee motorboat is marked “231”, has a faded price tag for $2.00, and is marked “Kaufmann’s, Fifth Ave, Pittsburgh”. There were no instructions on the boxes, and if paper instructions and rigging directions were provided, they have all disappeared. Many of the motorboats had the instructions printed on the bottom.

Collectors love original boxes, but there are no pretty Jacrim boxes, just a few corrugated cardboard shipping containers. Keystone was making all kinds of other toys and had a box manufacturer lined up. An early Keystone box for a ferry boat listed Keystone Wood Toys, Inc. as the manufacturer. This was a plain cardboard box with the date printed on it. The later Keystone sailboats were shipped in a triangular box with directions and assembly drawings printed on the box. This box could cleverly serve as a boat stand. These boxes lasted into the 1950s and probably to the end of Keystone. The toys, by the late 1930s and later, were in colorful boxes with illustrations and instructions, and many of those boxes have survived.

In 1934, Jacrim Wood Division of Keystone Manufacturing Company announced electric motorboats equipped with Eveready motors and batteries. Jacrim had an exclusive agreement with National Carbon to use the powerful Eveready motor and batteries in their boats. This motor was developed in National Carbon’s laboratories at a cost of $50,000 (a lot of money in 1934 when cars sold for $600.00). The motor in the 22-in model 1185 would drive the boat 150 ft/min and had an electric searchlight. It was priced with four batteries at $25.00 wholesale. The small electric boats used a motor designed and patented by Julius Pedersen and Marvin J. Dowell.

Not much more is known about the businesses, and what is written here was gleaned from an interview with David Rimmer, Playthings magazine ads, company catalogs, census reports, death notices, college records, and various books. The only hard evidence is the myriad of pond sailboats, wind-up and battery-powered boats found at auction, in antique shops, in flea markets and lately on eBay. Many of the boats were unmarked and probably sold to department stores and catalog houses, or the decal simply was worn off or removed for painting.

I believe that the early beginnings were quite crude by manufacturing standards. The wood shop at Cross and Main at one time employed all the brothers and probably Jackson. The earliest boat I have seen had an amateur poured lead keel weight and a cast brass nameplate. Sadly, I do not have that boat and cannot find out where it is now. The first series of boats were quite professional and were equipped with some neat features such as the spring-assisted automatic rudder, the brass washers under the metal eye hooks, the brass grommet at the mast base, and tapered masts. These features were not applicable to mass production and were costly. The earliest production sailboat was made about 1924, offered the square rudder, bowsprits, and shellacked decks, cloth sails, brass eye hooks with small brass grommets, and a dagger-shaped keel.

The following are early 1921 to 1924 Seaworthy boats without the Jacrim name.

These early boats had a spade keel, a square rudder, and a lead weight fixed to the bottom of the keel parallel to the deck. The name tag was a cast brass tag mounted on the stern.

The lumber was probably delivered precut in blanks long enough for each hull. Then the outline was drawn using patterns, and each was sawn with a bandsaw and sanded to final shape.

I was contacted by a man who worked for Keystone in the summer of the late 1930s. He said that most of the work on the hulls was done by one man with a large sander. The hollow boats were drilled on a drill press with a large Forstner bit. The decks were cut with a bandsaw, fastened with nails, and then shellacked. The hulls were painted, screw eyes with brass washers were fitted, masts and sails were added, and common string was used for the rigging to finish a boat. The boats were shipped unassembled, and there were some printed instructions on assembly and sailing, but none have survived.

Soon the sailboat keel was changed to the classic cut sheet metal shape with the lead weight fixed to the bottom that was used right into the final days of Keystone. From observing other toy sailboats from that time, it appears that either Chester collaborated with them on design or his keel shape or it was just copied, probably from Tillicum (Milton Bradley) in Boston and Rochette Consolidated Toys in Methuen. Rich sailboats also used the same basic shape as Rochette. I have found only one patent with Chester’s name, and that was for a rubber band-powered or outboard motorboat; so none of the sailboats were patented.

The wood hulls were finely shaped and are a tribute to Chester’s skill as a Naval Architect and to his brothers’ skills as woodworkers. The boats float on their waterlines and will sail. The Seaworthy and Jacrim boats had many hours of shaping and were beautiful to observe. The delicately balanced transoms and clean rounded hulls gave way to machine-cut shapes that Keystone’s cost cutting and mass production dictated. Dating the production boats shows the steady change to cut costs and to eliminate hand work. The Rimmer brothers were woodworkers, and their products showed it.

The masts and booms were dowels tapered at the ends with a wire loop for a gooseneck and cotton sails with brass eyelets. Other changes were made for economic reasons by Keystone. Prices were incredibly low, but at that time beer was probably a nickel a glass. The Butler Brothers wholesale catalog listed the 19-in Pirate at $2.40 each, while the 13 ½-in Kitten catboat was $8.00 a dozen. The 26-in sloop was listed as “really hollow” and had a raised deck, cross tree, automatic rudder, and adjustable stays and sheets for $6.00. The 1931 Playthings advertisement showed 20 sailboats and seven motorboats and two Tom Thumb boats. One of the motorboats was rubber band-powered.

The early wind-up motorboats were marked “Flying Yankee”, had the Seaworthy label, and were probably made from 1924 through 1932. The Flying Yankees were made from 16 to 27 in. They used a hand-cranked spring motor and were shaped from glued pieces of solid wood and were quite heavy. The bigger boats had wheel steering with cord directed to the tiller under brass tubes on the deck. The motors seemed quite strong; I ran a 27-in model twice the length of my 40-ft pool with the propeller still spinning. These boats did not exhibit much speed because they were quite heavy. I then ran a 1937 Keystone wind-up and found it to be a little bit faster and much lighter. The smaller 14-in Keystone performed best, looking like a motorboat. Seaworthy only made the solid wood boats. Keystone made a range from 8 to 27 in. These were made of thin wood glued together like real boats. The largest boat was quite detailed. The hull reveals the extent of Keystone’s production ability. The solid wood hull was completely machined and was not hogged out the way it was done at Jacrim. The Keystone catalog called these wind-up toys Featherweight boats because they were substantially lighter than the old solid wood Seaworthy motorboats. The smaller boats were modeled after Chester’s patent with rubber band power, outboard wind-up boat, battery electric motorboat, and internal engine wind-up boat.

The February 1, 1934 catalog of Keystone Manufacturing Co. Jacrim Wood shows the last of the classic boats. After that, every change was made to cut costs and ease manufacturing. By the 1940s the natural deck gave way to the printed deck. By 1950 sails went from stitched cloth to plastic Vinylite, and the hulls were completely machine shaped. Fittings were made of plastic, and the steering wheels disappeared. Even so, a Keystone-made sailboat with a printed deck is an impressive sight. The spring motorboats ran well and looked like real boats, but manufacturing only lasted about 10 years past the war years.

In 1938 Keystone Manufacturing at 288 A Street, Boston published an advertisement in Playthings that touted boats, desks, cradles, forts, doll houses, and steel toys. No pictures, details, or prices were listed. Besides toys, Keystone was developing movie cameras and film.

Much of the business was from catalog sites and department stores and other retailers who purchased products by the dozen or boxed. The 1938 N. Sure Co. (from Chicago) catalog listed a spring motorboat 13 ½ in long at $3.92 per dozen; a 24-in sloop with brass pulleys, pennants, staysail, jib, and main at $2.10 per dozen; a 26-in sailboat at $2.50 per dozen; and the 28-in sailboat at $3.50 per dozen. The smaller 19 ½-in boat was $3.92 per dozen; 14-in, $2.00 per dozen; and 21-in, $7.84 per dozen. A special 24-in sailboat with working compass and brass rails was $16.50 per dozen. The Keystone Deluxe K-5 18-in wind-up boat was $21.00 per dozen. Earlier in the 1930 catalog the 18-in Seaworthy wind-up boat was $7.90 per dozen.

The war in 1941 changed everything, and sailboats were a small item in the 1942 price list. Steel for keels was difficult to buy, and Keystone began making more wood boats. Now warships were the rage with battleships, cruisers, aircraft carriers that launched planes, submarines that fired torpedoes, and even an exploding boat with a mousetrap-like spring that would cause the boat to fly apart when struck by a torpedo or missile. A large range of war boat toys were offered. These toys were meant for the living room floor and not for the water. Some of these shapes were like Chester’s Tom Thumb toys of the early 1930s. This also was the beginning of the end for the natural wood deck. By 1942, all of the decks were printed or painted.

The trend was clear. The 1938–1939 catalog showed five pages of projectors, four pages of steel trucks, four pages of doll houses and furniture, two pages of forts, two pages of boats—one for motorboats and one for sailboats. The 1940–41 catalog showed five pages of projectors, three pages of steel toys, three pages of doll houses and furniture, two pages of war toys (battleships, a submarine, and an exploding boat), a half of a page of motorboats, a half of a page of sailboats, and a page of a pump fireboat and cargo boats. 1950 saw a special boat catalog featuring a canoe with sail; a 9-in catboat; 12-, 16-, 20-, 22-, and 24-in sailboats with Vinylite sails; a ferry boat; two fishing boats; a pumping fireboat; and a wind-up tug boat with a barge. The 24-in sailboat had a hollow hull. The counterweights on the sailboat keels had changed from lead to welded steel.

Chester Rimmer stayed with the company and retired in1957, and Keystone continued until 1973. From 1953 through 1959, he was listed as president-treasurer of Keystone Wood Toys at 143 Hallet St, Dorchester, MA. He offered a wood PT boat under the name of Admiral Chester. I have only seen one of these boats.

Chester suffered from Parkinson Disease as he grew older and died February 2, 1984 in Norwell, MA. He is buried at Puritan Lawn Cemetery in Peabody, MA. 1973 is the last year Keystone Manufacturing was listed in the Boston City Directory.

I encourage anyone with information to share or questions to contact me at seaworthy1924@yahoo.com.

Other Manufactured Boat Articles

- Manufactured Boats Introduction

- Jacrim, Keystone, and Seaworthy Boats by Bob Jones

- Keystone Manufacturing by Derrick Clow

- Keystone Company Timeline by Derrick Clow

- Keystone Manufacturing Company Locations by Derrick Clow

- Model Yacht Manufacturers and Sellers

- Estimating the Year of Manufacture of a Boat: Jacrim, Keystone, Seaworthy by Bob Jones

- Keystone Toys by Derrick Clow