- Bolero design: A full-keel “A” Class yacht by H.E. Andrews, challenging the traditional view that full keelers are poor for racing. It explains design principles like moving the stern post forward and avoiding hollow garboard diagonals to improve performance.

- Construction tips: Notes on weight calculation, universal joint for rudder stock, rigging details, and the importance of using pure lead for ballast.

- Radio control and waterproofing: Advice on sealing deck houses, protecting batteries, aerial placement, and avoiding water ingress in electrical components.

- Performance improvement: Emphasis on reducing skin friction through meticulous hull finishing—priming, undercoating, and careful sanding for better light-weather performance.

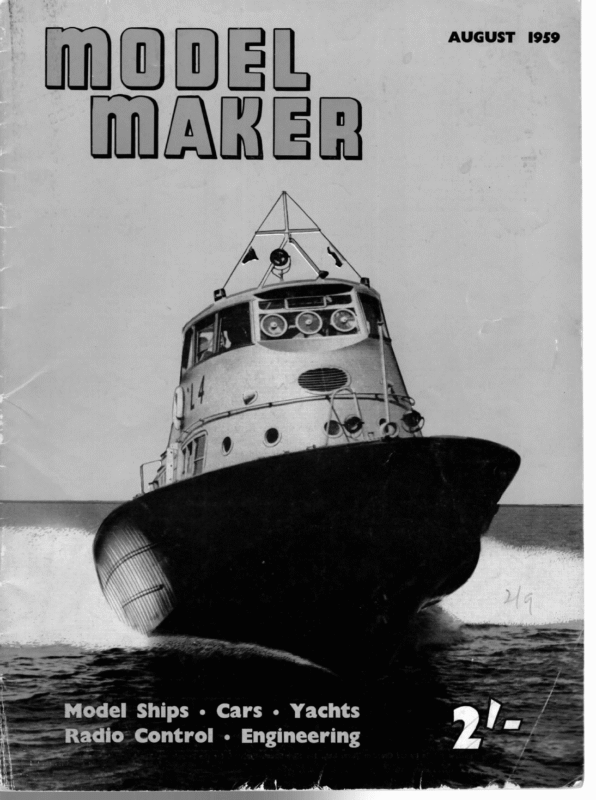

MODEL MAKER} ere 2 ey — eee FB Les. 355 Bs. Les 5 LBs. Les a ; | | if any of the normal tuning procedures, she was / ) | r | v \: KS T } Fotis / | | \f Hy y] HULL, DECK, DEADWOOD & Ni \ —— Sz Qans eee = 39:22 15-69 2a aa 54931392 23.53 + 15-69 Pe vo 4 2, 1270 ~iSA, ne EN AL oise maxtd mw mind: Ka or: AK » 9453 2: ; th 8 5° 5: 44 HERTS decay bir taat WATFORD. #0. CLAMENOON 38. es $4-93+39 te = | MODEL MAKER PLANS SERVICE oF & Cesiento copvaicnt BOLERO H.E. Andrews. @ Fr OR many years now it has been regarded by British model yachtsmen as the law of the Medes and Persians that a full keel boat to the “A” Class, or any other Class, is useless for competition purposes. So deeply ingrained has this feeling become that the only designer ever to essay one in this country, was the late Bill Daniels and even he only did one as ordered by a well-known ‘‘full-size’” yachtsman who wanted an “A” Class on the lines of his 12Metre yacht. Thus we had Modesty in the inter-war years and Eyaine in the 1950’s, both beautiful boats as only Bill could draw them, but both relative failures. Whenever the subject is mentioned an argument is sure to ensue and although the type’s protagonists (very few and far between) quote the two Championship successes of Kai Ipsen’s Revanche, the last one in 1954, it is usually to no avail as the other side always tend to dismiss this boat as a lucky fluke sailed by a superb skipper, thus unwittingly denying to Kai the honour due to him as a skilful designer. Admiring, as we do, the full keeler’s undoubted beauty, their reputation, undeserved in our opinion, has been a perpetual challenge and we have given considerable thought to the problem over a number of years. When, therefore, the opportunity arose last autumn to design for a member of the Poole M.Y.C. an “A” Class that ‘‘looked like a yacht’’, we seized the opportunity with both hands. The design now published as Bolero was the result. The prototype, Falcon, built and owned by Mr. R. Dehon and wearing Poole’s burgee, was launched recently at Gosport under conditions which were atrocious for a new boat, a wind of 20-25 knots accompanied by heavy and continuous rain. With no time or opportunity for a” SS et i : 332 sailed against a representative collection of Gosport boats in a race, for the first part of which we had to concentrate on finding the trims. In the second half we started to race her and immediately began to find the points. Quite apart from the fact that she was sailing 3 Ib. under designed displacement, she showed exceptional promise for both to windward and loo’ard she held her own with some of Gosport’s best and showed none of the vices traditionally associated with her type under conditions which would be expected to reveal them in full measure. When we brought her out Gosport regarded her as a well cared for “‘old timer’’, because of her full keel, but their sotto voce comments after the race were, ‘““When that b. . . Falcon gets tuned up she will need watching.” With

AUGUST, Bolero. This proved full-keeler from Harry 1959 ie LWL. 2 Fig 1 Andrews makes a refreshing change in racing yacht design Fig. this guerdon we accepted that she had passed her main test and justified herself in a good trates the a years. waterline and also for the stern post to descen d at a fairly steep angle. (Fig. 1.) It is appare nt that with this hull form there is plenty of deadwood in way of the garboard stream, for it to work its way upon. A further effect of this positioning of the stern post is the necessity for hollow lines in the after garboard, particularly of the garboard diagonal. The garboard stream passing these hollows at speed tends to cause vortices which have a slowing effect on the loo’ard side of the boat, again tending to turn the boat off the wind. In the old days of the Braine gear, when a yacht relied solely on the balance betwee n C. of E. and C.L.R. to get her to windward, these defects were fatal and thus began the full keeler’s notoriety. It has long seemed to us that the answer to this problem was twofold, (a) to move the stern post as far forward as possible, and (6) careful design of the after end of the boat, particularly in way of the garboards, to avoid any suspici on of hollow in the garboard diagonal. It will be seen that in Bolero we have acted on these two principles, and it seems from the prototy pe’s behaviour that they are the key to the problem. ee HARD SOLDER {0 B.A. NUT & BOLT RIVET 2 BA. THREAD Fig. 2 ge & LOCKNUT 7! Gi steering gear Bolero should be a fairly easy boat to build, either plank or bread and butter, and the weight schedule is well within the compass of any a tendency for it to push the stern of the boat up to windward, thus making her run off the or very for ence in connecting the boat is travelling at reason shows the method of universally jointing the rudder stock for conveni- fast and heeled. If any of the boat’s deadw ood is in the way of this rising stream, there may be top of the stern post to be sited —— of sternpost the bad name this type of keel has had for some is indicated. When a yacht is sailing heeled a fast stream of water runs along the loo-ard garboard following the line of the garboa rd diagonal. Towards the after end of the boat this stream of water is angled across the centreline of the yacht and seeks to escape upward s and to weather just as soon as it can. When it does, it causes the heaped wave on the weather slightly forward of the after end of the load the which may be For the benefit of many readers who may never have seen a full keel yacht, a bit of theory wind and fail to hold her true course to windward. With most full keelers it is traditional for the illus- pesto company of fin keelers. quarter so often seen when a 1 traditional amateur builder. A word of caution is, however necessary. The lead is calculated using the “scientific” figure of 11.4 for the relative density of lead. When Mr. Dehon built Falcon he used scrap lead for the ballast casting and this proved to have a relative density lower than 11.4 due to impurities. This resulted in the keel being two pounds light. Care should therefore be taken to use only pure lead. It is recommended that a simple form of universal joint be inserted in the rudder stock well above the L.W.L. in order that the top of the stock can come through the deck in a vertical position. Care should be taken to make this universal joint perfectly free-moving and yet free from any suspicion of backlash. Fig. 2 indicates the idea. Bolero should be rigged in the standard fashion, one pair of main shrouds and one pair of running backstays. These should be controlled by slides or, preferably, by Highfield levers. A pair of jumper struts at the hounds and a permanent backstay should take care of the tautness of the forestay and the line of the top mast. Bolero is a lightweight by modern standards, coming as she does, at the lower end of the displacement band for her length, but her reasonable beam coupled with a firm midsection enables her to carry her sail well in a blow; she has little, if any, more wetted surface than a comparable fin keeler and her light weather performance should be up to standard. 333

MOO EL MAKER) PART TWO OF A SHORT SERIES GIVING FACTUAL INFORMATION BY EXPERT J. C. CEMENT PUSH OR CREW-ON CAP. a HOGG Foam. 16 SW.G. WIRE DECK é ; POLYSTYRENE BRASS OR LOCATING CONE COMING ASHORE Radio RUNNING BACK 7 TACK TO STARBOARD -(LET OUT SHEETS WHILE PAYING OFF) 2 = ay, — TACK TO PORT y TIME MINS. PORT TACK =. STARBOARD TACK TACK TO STARBOARD ~) STARBOARD TACK | PORT TACK — 30 2010 410 20 30 } smestee ee — reg ¥) Controlled Yachts ‘*Watertightmanship”’ Radio equipment and salt (or even fresh) water are poor mixers. In R/C yachts it should be assumed that the decks will be frequently awash. Well fitting deck houses bedding down on to foam plastic is one solution to the problem. The plastic forms a very effective wet seal which will stand up to severe weather conditions. Bringing the rudder and winch rods through the top of the deck house is convenient, but care should be taken to fit rubber glands. A method I have used in the ““M” and “A” is to bring out the sheets and rudder rod aft of the housing. This is safe—even on Poole Lake! Milliameter sockets are a source of trouble if they become wet. If they are needed frequently, pins should be soldered on to the plug of the meter and a sheet of rubber stuck on the deck house above the M/A socket. The pins will pierce the rubber sufficiently to make contact but not sufficiently to allow water to pass in when the plug is removed. Incidentally, one still sees shorting plugs used for milliammeters—a quite unnecessary nuisance. The sockets can be shorted permanently with a small 250 ohm resistance, which will have very little effect on the accuracy of the meter. TACK TO PORT ) P 7 THIN = ——= RUBBER run and when ready send a radio signal to start the recorder. The recorder stops itself after one revolution of the drum. A typical chart is shown. This represents the rudder movements on a Marblehead tacking out to open water, going about and running back again. Normally the test would be taken on a steady leg of a course, but this one shows the effect of the proportional rudder, under various points of sailing. I think that quite an amount of information can be obtained from a close study of such records, especially when used for comparison between hulls—and skippers! From the control aspect this particular chart shows that the rudder can be moved rapidly or slowly as desired or can be left amidships or at any other position. Other information which can be recorded on this instrument is “pitching” and “heeling” and speed. CORRECT AGAINST A GYBE LV h! 7 PINS SECTION THROUGH DECK HOUSE. WATERTIGHT FITTINGS D ( M/A METER PLUG THICK RUBBER START S}TRUDDER POSITION CHART Rudder position A dial indicator mounted near the shrouds shows accurately the rudder position to compare with the tiller on shore. It is interesting to see the amount of “‘weather’’ or “‘lee’’ helm required by a model under various conditions. More recently a small chart recorder has been made which records the movement of the rudder on a clockwork driven chart (2 in. = one minute). The recorder is mounted on deck and the method of operation is to sail the yacht into a suitable position for the test Photograph on left shows the complete chart recording unit which is mounted on deck and runs for something over three minutes, using a ball-point trace. Centre is an actual chart from this recorder, and another is illustrated as a tracing in the line drawing above. Photo at right shows the author’s small hand transmitter built for experimental handling. Photograph on opposite page shows the double-headsailed cutter Sunray used as one of the experimental sailing models for measurement tests, etc. 344

AUGUST, 1959 when required. It also keeps the aerial clear of water sweeping the deck. The aerial is then led up the mast, care being taken to see that the main boom can travel out fully without fouling the aerial. These points are illustrated in Fig. 3. Batteries generally suffer first if the boat makes any water. If they are kept in the hull outside the control box a taped up polythene bag will keep out the worst, but it is more satisfactory to have them in a wooden box shaped to fit low in the hull, and waterproofed. Batteries in the keel itself are not to be recommended. Control System Switches also have to be in an accessible position on deck houses and can suffer in consequence. These also can be fitted beneath a rubber membrane (balloon thickness) and be operated through the rubber which keeps them perfectly dry. Aerial lead-ins are notorious sources of trouble. I find it best to make a watertight plug which passes right through to the receiver. This is easily removed READERS WRITE suggest a remedy. There have been many ideas and descriptions of the methods of linking the radio receiver with the servo motors to obtain the desired control and it is as well at this stage that no one system should be rigidly adopted, but rather that they should develop freely. The following system has been tried out on my models in various forms. Any reliable type of receiver may be used with it provided a current swing of about 4 milliamps is obtainable. Variable mark/space signals are used. For this reason it is not intended to describe in detail the transmitter or receiver. Usually I have used a stationary transmitter, but last season I made up a small portable one to study the advantages of being able to move about while sailing the model. The multivibrator to generate the mark/space signal comprises two transistors driving the transmitter directly without the use of a keying relay —this saves space. The use of a hand TX certainly has many advantages, particularly when studying boat performance, and aids the operation from the “put in and go” aspect. For contests however, I believe that moving about to any great extent distracts one from the control of the model and shows little advantage over the stationary transmitter. (The idea of two competitors luffing one another off the pond, the pond side, and the frequency, is a formidable one!). (To be concluded) One enthusiast told me (more letters on page 342) that he cured the trouble with fibre glass, but he had to beat his engine apart to change the liner! MARINE MURK Dear Sir, Inthe Mopet Maker report dealing with the E.D. 2-46 c.c. Marine engine, it is stated that while the seal between the exhaust mani- CATAFAN fold and stubs is good, the engine will continue to run if the stub pipes are completelv closed. I would suggest that this is because the engine is exhausting via the gap that exists between the top of the crankcase casting and the water jacket; as the water jacket is used to clamp down the cylinder liner it cannot obviously seat firmly on the top face of the crankcase. I use stub extensions on my E.D. 2:46, though I prefer those marketed by Messrs. Ripmax, as they do not have the 90 degree turn as do those of Messrs. E.D., and consequently the leadaway pipes can be taken well clear of the fly-wheel for ease of starting However, a considerable amount of fumes, oil and general slush does find its way out of this gap beneath the water jacket, and it is this, combined with an occasional drip from the front bearing, that makes this excellent engine so dirty to use in a boat. I did endeavour to seal the gap, by soaking a piece of thick string in Ozotite, and carefully fitting it to fit round the outside periphery of the step on the underside of the water jacket. This was clamped down while wet and allowed to dry. After about an hour’s running the fuel dissolved the Ozotite, and once more the fumes poured forth. It struck me that other readers must have suffered similarly, and may be able to Eastbourne. L. R. TANSWELL. Dear Sir, When I bought a MopEL MAKER Manual last summer, the plan which interested me most was that of Sea Cat. It was just the plan I had been looking for, because although I was interested in model yachts, my building experience had been very little. Although construction was simple and straightforward, the boat was not tried out until last October, when her performance startled me. On this particular day there was hardly sufficient wind to drive my 36R boat but the catamaran “ghosted’’ across the pond at quite a decent pace. Since then its speed has never ceased to amaze me. The allround performance is really phenomenal, as it nearly always beats my 36R hollow, and I have had Sea Cat going with spray halfway up the mast! To date it has capsized only once, and that in a force six wind, in spite of two pounds of lead strapped to the decks. The main faults with my boat are (i) a tendency for the bows to dig in, especially the lee one; (ii) when struck by a cat’s-paw the boat tends to slow down and (iii) inability to point high into the wind. he lead containers can be seen in the photograph aft, on the deck. Half a pound of lead is usually carried in these, and for extra heavy weather, greater amounts are strapped amidships. My Sea Cat weighs 3} pounds and has approximately 375 Square inches of sail area. Master D. M. SHAW. Barnsley, Yorks. 345 (@ All catamarans tend to stub the leeward toe due to lack of reserve buoyancy in the bows unless an excessive overhang is employed. (ii) The penalty of a light boat is lack of inertia to carry it through wind flirts. (iii) No catamaran will point as high as a conventional craft, but superior speed often offsets this —Ep

Su MODEL MAKER) IMPROVING PERFORMANCE OF MODEL YACHTS Conclusion By R. H. Morrell Excessive Skin Friction In all branches of modelling it is noticeable that “finish” is, generally speaking, the art in which least workers really excel. that are beautifully second-rate (perhaps How often one sees models constructed, a but have third-rate) finish. only a Earlier we made the point that in light breezes skin friction can represent a big percentage of the resistance to forward movement that a yacht has to overcome. It will therefore be appreciated that the obtaining of a really good surface, as free from friction as possible, is a very valuable feature for light weather work. How then shall the desired standard of finish be obtained? The first essential towards obtaining our objective is to greatly increase the amount of time spent in preparation. Most builders are filled with keen anticipation as their model, the product of so much work, nears completion. “I’ve only to paint her, now,” they say, and, bless them, they are simply longing to smack some colour on and see her complete. But good finish is very much a case of “make haste slowly”! Avoid all temptation to hurry the rubbing down process; keep at it, progressively changing to finer grades of glasspaper, finishing off with a really fine grade. If this is done unhurriedly, the wood of the hull will gradually assume a splendid smoothness like a dull polish. Obtain this, and you really are working towards “good finish.” i tat The next stage is to give the hull a coat of “priming.” This can be of either flat paint or varnish, in either case thinned by adding about one- third turpentine. This thin priming will soak well into the wood and help to preserve it. When thoroughly dry, rub down again lightly but thoroughly with “flour” glasspaper. Now foiiow with a coat of good quality undercoating. This, too, should be carefully rubbed down when completely dry, and the procees again repeated. Actually, there are many degrees of good finish, and it is just a matter of how far one desires to carry the process. An old coachbuilder ance described good finish as “putting on twenty coats and rubbing off nineteen”! This, of course, is going to the extreme and is not suggested, but the principle is worth remembering. Actually, two coats of undercoating after the thinned primer, and then one or two coats of the finishing paint will produce very good results if the rubbing down is carefully carried out between each application. Especially for the finishing stages, a fine grain of “Wet or Dry” abrasive paper, used wet, is very effective. The question of colour schemes has not been touched on, as this is purely a matter of taste. A two-colour scheme will, of course, necessitate careful masking of first one side, and then the other, of the L.W.L. to ensure a clean, sharp dividing line; narrow Sellotape will be found useful in this connection. Needless to say, first-class work calls for firstclass materials, and it is pointless to waste one’s time with cheap brushes or inferior paint. Good brushes are fairly expensive, but if carefully cleaned after each time of use they will last indefinitely. The old-fashioned way of using flat paint and finishing with a coat of varnish produced some very good results, but a modern synthetic finish, such as “Robbialac” or “Valspar,” will probably be preferred. Dust and particles of paint-skin are the bugbear of all painting, and the following points are worth careful watching :— Make sure that your paint is free from particles —strain it through a couple of layers cut from an old nylon stocking if in the least doubt. 2. Don’t work in a room which has recently been swept or “stirred up” in any way. The cleanest rooms contain dust; so the less it is disturbed, the better. 3. Make sure that your brushes are perfectly clean and free from dust. Store in a box when not in use. 4. See that your hands are perfectly clean at each stage of the work (unless just washed, they will have traces of natural “skin oil”). 5. Don’t wear a fluffy type of suit, or clothes that are dusty. This may seem obvious, but many a man has finished “rubbing down” and then commenced painting, quite overlooking that his suit was covered with fine dust! Possib!y the reader wiil smile rather wryly and say: “If I observe all these things I shall DESERVE a good finish!*—you will, friend, but we think that you will get it and feel the trouble worthwhile. If you DON’T want to go so far, go as far as you fancy, but do get away from the treacly, brushmarked finish that kills the light-weather performance of so many yachts! 358