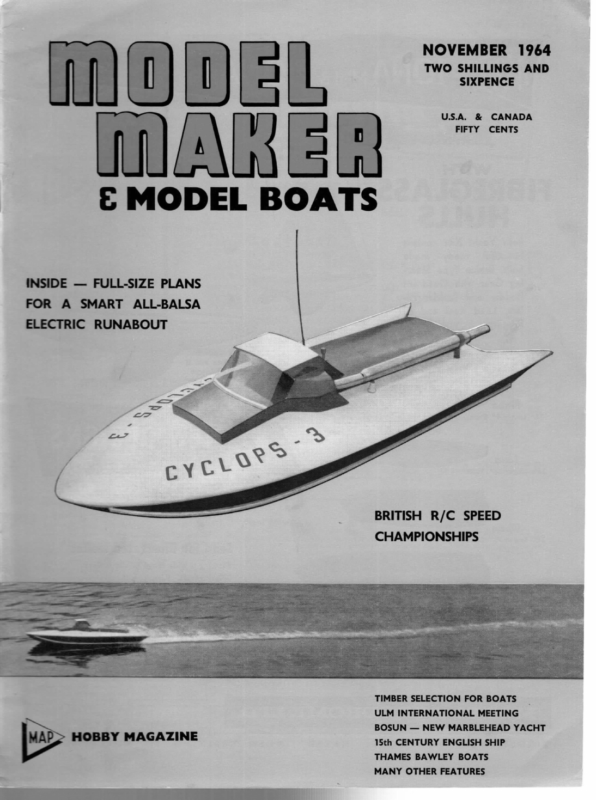

NOVEMBER 1964 TWO SHILLINGS AND SIXPENCE U.S.A. & FIFTY CANADA CENTS & MODEL BOATS INSIDE — FULL-SIZE PLANS FOR A SMART ALL-BALSA ELECTRIC RUNABOUT BRITISH R/C SPEED CHAMPIONSHIPS TIMBER SELECTION FOR BOATS ULM INTERNATIONAL MEETING BOSUN — NEW MARBLEHEAD YACHT HOBBY MAGAZINE 15th CENTURY ENGLISH SHIP THAMES BAWLEY BOATS MANY OTHER FEATURES Mi

WITH / FIBREGLASS HULLS Both Yacht Kits contain beautiful ready made fe Sails, Braine Type Steering Gear with Quadrant Rudder and lars, Lead Rudder PilKeel and all Ae , Rigging. _ KINDLY IN – Send for illustrated leaflet showing a wide range of the famous “Marinecraft” Kits. ave 24″ Main Agents Repair Service Be MENTION for: Scalextric Cars SG SE Spra 383” Leng Y “va WR SS SSS SSE SSS SSS XC SANSA – = IS) NS) Ni SG Ee “MODEL MAKER” WHEN Triang Trains Thimbledrome Aircraft REPLYING TO ADVERTISEMENTS

In Tideway AS is customary during the A Class Championship Regatta, opportunity was taken for the A.G.M. of the International Model Yacht Racing Union, under the Presidency of M. Horace Boussy of France. National authorities represented were Belgium, Holland, France, Italy, Germany, Denmark, Scotland, and England. Two main points of general interest were the Presi- dent’s reference in his report to a new European Association endeavouring to control the sport on the Continent and the acceptance of the Q class as an international R/C yacht class. If we may comment on these points, we would like to mention that if the new European Association re- ferred to is Naviga it is not trying to control the sport. The position in most European countries is that there is often wide interest in sailing craft, but very little national participation in organised activity. Naviga feels that many enthusiasts would like to belong to an organised body, but do not know about it or do not find the existing facilities covering their specific needs. Many of these people are members of clubs, usually power boat clubs since there are few yacht clubs existing; most power boat clubs are affiliated to Naviga through their national bodies. Naviga is therefore anxious and willing to co-operate with national sailing bodies (and hence the I.M.Y.R.U.) to ensure that these sailing enthusiasts are more adequately catered for. There is no question of usurping the function of any other established authority, and we feel that their desire to work in with other bodies is likely to result in mutual benefits for all concerned and is therefore praiseworthy and deserving of consideration. In a way, this all ties in with radio control and therefore, to some extent, has a bearing on the Q class. Naturally we are pleased that this English 1964 A Class Champion ‘Debutante’ — see text. innovation has received international recognition, but our honest opinion is that it is pretty much of a dead end. There is wide interest in R/C sailing in Europe, and international R/C yacht regattas are on the doorstep. But — there are very, very few A class yachts in any European countries, and only the possibility of one or two Qs. Most existing enthusiasts are sailing converted Marbleheads, because the Q is simply too big. We will never have popular R/C yachts until an internationally recognised small class is in being; we shall never have this unless sufficient craft are built to a class for it to be recognised as a class. And we shall never have a large enough number of boats built to an unofficial class because it is too speculative to build one only to find that another class is to be recognised. What is needed is a lead — if a rule is made boats will follow; surely that is common sense? At the moment Marbleheads are used, but the owners mostly consider them a stopgap and would far prefer a graceful craft with overhangs — say about | metre waterline, 10 kilos maximum, plus a simple sail area restriction, which would produce a pretty and portable boat. Measuring waterline difficult? A thin floating rectangular frame to the maximum dimensions allowed; if the boat, floated in it with centre lines coincident, submerges the frame, it’s out of rating. A pair of scales and a ruler is all that would otherwise be needed. However, we are once again digressing. It would be nice to see an official lead on this question, though, wouldn’t it? Debutante We have now received some interesting details of the A class champion at Gosport, Debutante. She was built by Donovan Pinsent of Paignton M.Y.C. and is owned by Mrs. Pinsent. The designer is G. K. Collyer and this is his first attempt at a model design; he has designed and been very successful with ocean racers for a well-known full-size firm. Design figures are 1.o.a. 80 in., Lw.l. 55, beam 168, draught 123, displacement 61 1b., lead 47, sail area 1,582.5 sq. in. She is rib and plank built in mahogany and came out 14 Ib. overweight, giving a 56 in. w.l. She was afloat for the first time a month before the championship, and the following day won the Munster Cup, skippered by R. Gardner (who sailed her at Gosport) and mated by the builder. North London Exhibition Our heading picture shows some of the boats on show at the N.L.S.M.E. exhibition at Southgate, which was quite a success. About 1,500 paid for 510

NOVEMBER admission, 500 rode on the steam trains, and a similar number tried electric car racing. We liked, in the Society’s latest news sheet, the tales of the woman who, offered a ticket for a train-ride, said “Whatever would I do if I won it?” and the small boy who, being helped on the same train, turned the locomotive men puce by asking “Could I get an electric shock?” Timbers In this issue Ewart Freeston provides a very fine article on timbers, but to his recommendation never to use balsa we must add “Each to his taste”. If you know the quirks and limitations of any material you can produce a first-class job, and balsa is no exception. The same applies to parana pine; we agree that it is advisable to avoid these timbers for high class ship work if you do not know them intimately, but our experience is that they cannot be condemned for those experienced in their use, or when recommended for a subject the design of which takes into account their foibles. Norman A. Ough Following his earlier illness, Norman Ough has once again had to spend a short while in hospital for a check. This has meant that he has been unable to provide a “Warship Detail” article this month, but he stresses that his visit to hospital is this time a short one and hopes to be back at the board within a few days. Lost J. M. I. Reeves, Aerodynamics office, British Aircraft Corporation (Operating) Ltd., Bracklands Road, Weybridge, Surrey, is looking for green/blue/orange sea sled powered by two P.A.W. 19 engines lost, stolen, or strayed on the River Teign Estuary on the last day of August. Any information gladly received by him or can be given to the nearest police station. Silver Solder Bill Tomkinson, well-known Northern engine man, has been designing and building engines for 40 years, and retired a couple of years ago from the position of tool-room boss at one of the best-known machine tool works in the world. Lately he’s been specialising in carburetters and magnetos — he has done beautiful conversion jobs on a good many motors up North — as well as making “Arderne” engines for one or two individuals, and we are hoping to persuade him to jot down a few notes on engine matters. However, why we mention him now is because he comments on the silver-soldering of cast iron as mentioned in our September issue by L. C. Mason. He writes, “Cast iron will not silver solder using hard silver solder and borax flux. The secret lies in using Johnston Mathey “Easyflo” flux; with this flux it is pos- sible to braze even aluminium bronze, one of the worst of metals to braze or silver solder’’. Thanks for the tip, Bill —that’s the useful sort of knowledge that people store in their minds. Any other readers like to send similar “secrets” in? Help American reader, Dr. Phillip L. Howard of New Haven, Connecticut, informs us that he is on the look out for a set of plans for H.M.S. Prince of 1670. Apparently drawings of this vessel by the late Clive Millward are out of print — at least Dr. Howard 1964 can’t get any — and those of the ship which he ob- tained from our own Science Museum are lacking in detail for scale modelling purposes. If you know of the whereabouts of Prince plans, drawings, sketches, etc., that may be of use to the Doctor, we feel sure that he’d be obliged to hear from you. His address is Pathology Dept., Yale Medical Center, Grace-New Haven Hospital, New Haven, Conn., U.S.A. John Lewis replies on ‘Joker’ I was very interested and glad to read Mr. Rayman’s remarks on my proposed design Joker for a steering competition boat. Firstly the notes did make it pretty clear that the design was a personal choice of features rather than a recommendation that the design is the only and best way to obtain straight running. As far as weight and size are concerned the boat is no more unhandy than a modern International A class model yacht and they get around well enough. I must admit that my statement that “a steam plant is necessarily heavy” as a statement is a fallacy as Mr. Rayman rightly points out. I had already made up my mind about flash steam and I was comparin g a centre flue boiler plant with petrol or diesel engines. I should have made this point more clearly. I did not say that I disliked flash steam. I said that a centre flue boiler is preferable and in the context of the article I still would make the same choice. Flash steam plants have a great deal of fascinati on and I would thoroughly enjoy operating one again. I say ‘again’ because before the war I spent many happy hours running a flash steam steering boat and during the same period I watched with envy the beautiful Silver Jubilee winning trophy after trophy. However, Silver Jubilee was an exception and Mr. Vines who ran her was an exceptionally experienced man in this type of contest. I do not think I could emulate the success of Silver Jubilee with flash steam so I chose a pot boiler and design of hull that will carry the weight easily. In my notes I cannot see anything about ‘flogging’ engines out of the water. As an engineer I would not recommend this practice but one must admit there is something quite nice about running a plant in the workshop (making use of the steam valve on the engine to restrict revs). Mr. Rayman’s remarks about the bow overhang and the sky fins as he calls them puzzle me a bit. In my notes I made it quite clear why there is a bow overhang and why there is extra lateral surface pro- vided to balance out ‘weather cocking’. I can assure readers that I was not ‘drifting’ back into yacht design but that these features are the result of considerable experience with this type of hull. A flat bottomed hull without a bow overhang would not have served the purpose intended. I have little doubt about the inherent straight running tendencies of the design. I do agree that the most difficult part of the whole project would be the making of two identical handed propellers. But is this impossibly difficult? I did not place the rudder where it is without thought. Normally one would use two rudders, one in each propeller stream. This makes manoeuvring easier, particularly at slow speeds, and rudders can be somewhat smaller. In our case we do not want this facility so let’s have one rudder only which is only going to act like a trimming tab to correct inaccuracies, if any, in building. We do not then have to worry about rudder linkages. 511 ) —————————————

”UAE The lines of the hull shown do not represent any Bosun New Marblehead by S. Witty LTHOUGH the writer is not a protagonist of heavyweight designs in any class, there can be no doubt that they do have certain advantages, par- ticularly on the larger coastal waters. With a displacement of 223 lb. Bosun should be powerful enough for anyone and will enable the high rig to be utilised to the fullest extent. particular evolution or new technique but will fill a demand for those who prefer an M class of rather more than average power with the minimum loss of performance at the light weather end of the scale. In the past designers have often been at cross purposes in their quest for greater heeled sailing length. In the light of present experience it seems that the main advantage of a full ended hull the fact that it is inherently better balanced. centre line of the immersed volume or Welch is straighter and the canoe-body as a whole has is in The Axis more symmetry and less tendency to “turn over the barrel” and follow the line of this curve as often happens in the case of a yacht with fine bows and canoe stern. As the speed/length ratio of a yacht is usually less than unity on a close beat more thought should be given to improving the characteristics of the lower end of the speed range rather than by concentrating on planing ability. By and large this means that finer ends (or fuller bodies) will tend to give better results providing they can be combined in a hull form which is tolerably vice free when heeled to extreme angles or driven hard. As it was suggested that I produce the lines of a hull of heavier displacement than those available I considered that such a hull could combine these characteristics yet retain the ability to plane in a blow if only as a “safety valve” to prevent the possibility of a jibe. 516

NOVEMBER there is a considerable break-through in hull shown can be very much improved upon without reverting to a bulb-keel as in the Vega concept. In this case, however, the fin is of normal configuration and is virtually the same as that of the Hustler design, except for extra lead in the keel. A subject of pondside argument overheard recently concerns the radius of the garboards, which is shown at one inch constant in the sections. Strictly, thotigh, this is not obligatory. The rules require only that the garboards in the way of the keel on or about the mid-section must have a minimum radius of one inch. Due to the extra volume of the hull there is a small overhang aft to help to absorb any increase in the height of the stern wave and to provide an ample length of tiller arm for the rudder and vane ji Bosun is a straightforward design in all respects. ear. TIMBER SELECTION [continued from page 515] yellow pine, Satin walnut, mahogany, walnut, sycamore, poplar and the like which when dismantled will provide him with more than enough for his needs if he discards any piece which is suspect. He should remember that for a ship model relatively little is required, and so he should select only those parts which are really good. Thirdly, he should build up a stock of timbers, store them until required and so be assured of a priceles cache of seasoned wood. Fourthly, there is always the.chance that he may be offered a tree, not, I should hasten to add, a 60 ft. lime, but an apple, pear or holly. If so, the only part he should consider is the butt that is, the part from ground level to the lowest branches, the branches themselves being relatively useless. If he is able to have this sawn into planks, is’ prepared to wait while the boards season, allowing a time of at least one year for each inch of thickness, he can become the possessor of a most useful stock to be drawn on as he needs, again remembering to retain only that which is perfect and discarding any which has the slightest fault. There are many other timbers on the market besides those I have named which may serve a model makers purpose and if you are thinking of using any of them the best advice anyone can give is to read all one can about its properties and if it is a likely timber, to experiment a bit with it before finally committing oneself to its use. I should like to add that I am willing to aid anyone who has a point he would like clarified, and that a letter addressed to me, care of the Editor, will, I am sure, be forwarded to me. Although she would have been considered very much a heavyweight a few years ago, at the present time her displacement is not exceptional. Like almost everything else, yacht styles change with time and whether a hull seems well proportioned or not depends largely upon what one is used to seeing. Even so, by any yardstick Bosun is an attrac- tive little craft and, with the experience accumulated through previous designs to the rule, I have no doubt her performance will be equally pleasing. Some sources of supply are listed below. TIMBERS FOR SHIP Type W. H. Clee, 9 Parkstone Avenue, London, N.18. Lime, Obechi, Ramin, Beech and most MODELS Supplier Lime, Sycamore, Walnut, Beech, Obechi. Peerless Timber Co., hardwoods. Middle Street, Brighton, Sx, Lime, W. Marshall, 317 Holloway Road, London, N.7. Lime, Je‘’utong, Sitka Spruce, Hornbeam. Chetham Timber Co., 229 High Street, Stratford, E.15. Box, Lancewood, Degame, W. Brine, Arlington Avenue, London, N.1, Pear, Holly, Ebony, Rosewood and most marquetry timbers. Yellow Pine. Ellis & Powell, 320 New Chester Road, Birkenhead. Honduras Cedar, J. Williams & Son, Christchurch Road, London, S.W.19. Western Red Cedar. Robert H. Hall Ltd., Paddock Wood, Tonbridge, Kent. British Columbia Pine, Canadian Hemlock, Sitka Spruce and other softwoods. W. Moore & Sons, Bruce Grove, * _. London, N,17, Practically any known hardwood or softwood in stock, and will supply any quantity. Ivens, Welton Station Sawmills, Watford, Near Rugby. . Hardboard and Plywood. Any good timber mercHant or . wine, ty Bristol Board. do-it-yourself shops, ete. Shops dealing in artist quirements such as Reeves; Rowneys or Windsor & Newton. 517 ee Unless contemporary M class design, I doubt if the type of 1964

nl SIGALE® SAILING MODELS discussed and some useful pointers for choice of a prototype provided by ]. W. Holness, A typical Hastings Lugger traced by the author from Science Museum material. CT is often said that scale sailing models are im- practical and that they must be made deeper and beamier in order to sail. Whilst this is generally true, the distorted models are not wholly satisfactory as they are not true models of ships. A large scale model of a small prototype has better proportions and the choice of types is very wide, as a visit to the Small Craft Section of the Science Museum will show. Towards the end of the 19th century, almost every port in the British Isles had its own type of fishing boat and there were also vast fleets of coastal traders whose form differed according to their place of origin. This field has been sadly neglected by the ship modeller, which in is a great pity, since the craft are interesting themselves and many are suitable for working models. Most of the craft were heavily built and carried ballast and cargo which, in a model with a light, strong hull, may be transformed to lead ballast and carried low down in the hull. This, together with the low sail plan, should give adequate stability. A point to bear in mind is that commercial craft so usually sailed with no more that 15 deg. of heel that, for realism, sail should be reduced as the wind increases. There are a number of considerations affecting the choice of a prototype. A convenient size, for a working model, is between 2 ft. 6 in. and 3 ft. 6 in. long, and about 25 Ib. maximum weight. Anything much smaller has not enough power unless it is a very heavy type; anything larger is too awkward to transport and too large to display at home. This means that a prototype of over 100 ft. long will be too small a scale and also that clippers or windjammers are out. Most British working craft, however, are well under the limit. Unless a local type is chosen, the prototype should have a stiff section, reasonable lateral area and draught, and sharp lines. For example, a Scots Zulu or Morecambe Bay prawner has all four; a Hastings lugger has only the stiff section, and most types of Cornish lugger have all but the stiff section. Open or partially decked boats are not really suitable subjects as the construction shows and therefore must be to scale, and, being ballasted, they may fill and sink in a squall. _ B.Sc., A.M.R.LN.A. Some form of self-steering gear is desirable and it is easier to install this in a boat having an upright rudder post and tiller steering. Models of Thames barges tend to be rather unsuccessful without additional fins unless they are fairly big, say over 3 ft. 6 in., when they are also very heavy. Of course, a model of a working craft should not be expected to sail as well as a racer, any more than the skipper of a smack would have expected to sail past a yacht. It should not be slow, but will make more leeway than a yacht, particularly if allowed to heel much. Unfortunately, not many drawings of working craft are available which are intended especially for modellers and these may not be to the right scale. In any case, the modeller will have to draw his own construction plans. The largest collection of small craft plans available is that at the Science Museum. These are in the form of small photo copies to no particular scale and great care must be taken in redrawing them to the chosen scale. A pair of proportional dividers makes the task much easier. It is worth taking some trouble over the drawings as a mistake in the basic framework means a waste of time and materials or an unfair hull. As mentioned above, the hull must be light but strong to. leave enough displacement to carry adequate ballast. The bread and butter method is a simple one, but involves much waste, hard work, and mess. It also requires some skill with carving tools if the hull is to be light enough. A far more satisfactory method, both in the execution and the results, is the frame and plank. This need not be difficult, though it requires more patience than bread and butter. The simplest method is to cut out one piece of plywood, of appropriate thickness, to the outline of stem, keel, and sternpost, allowing about 1 in. inside the rabbet line (where planking meets keel, etc.). Each frame is also cut from ply in a complete unit of deck, beam, frame and floor which is bevelled to suit the curve of the planking and then slotted over the keel. Chocks of quarter to half inch wood are then fitted against the keel, stem and sternpost and between frames, and are bevelled to take the plank ends and garboards (planks next to keel). On a model of the size we are considering 3 or zs in. 526

NOVEMBER ply is quite adequate for frames. The spacing, how- ever, will depend on the shape of the hull and the thickness of planking. The most readily available wood for planking is obechi in boards 7; in. and % in. thick. Planking ys in. is a bit thin, particularly if the model is likely to hit any driftwood, but will have to be used for clinker planking, for scale reasons. Also, it may be difficult to bend &% in. planking around a hull with a lot of shape, although this can be overcome by making the planks narrow. In fact, if they are made very narrow, say yj in. or 4% in., they may be cut straight as they will take enough edgeset to fit the hull. This technique, which is known as _ stripplanking, is widely used for yachts because much less skill and time is required for it than for traditional methods. A reasonable range of frame spacing is 23 in. to 4 in.; if the planking is thin or the hull has a lot of shape, keep the frames close, if not, choose a spacing to suit the length of the hull. After erecting the frames, the next job is to cut out the shape of the deck in ply, but cut out the middle except for cross pieces in way of the masts and perhaps the hatchways leaving about #3 in. round the sides. This is then fastened into notches in the tops of the frames so that they are flush to take the deck proper. This method provides a strong, rigid framework that does not need to be secured in a jig and enables one to get at all the parts of the model whilst planking. If the frames are deep, it may be necessary to let in a bilge stringer for additional support. The ply frames are not carried above the deck as the bulwark construction will have to be to scale. Notches will have to be cut in the ply deck outline to take the stanchions before planking is completed. If strip planking is chosen, it is probably best to start at the deck and plank down to the heel of stem and stern post, leaving an area to plank bounded by the straight keel and the curve of the last plank. This awkward area is the one snag of strip planking and is best filled by planking from the keel. The planks will have to be cut with long tapering ends to fit the curved plank. The traditional method of planking is tricky in that the planks are not only tapered but are curved in shape. It is necessary to divide carefully the frame girths by the number of planks and mark the widths on the frames, otherwise one may have to fit some odd shaped planks. Planking may proceed from keel to sheer or from keel and sheer to the turn of the bilge where the planks are generally straight. The latter method is probably the better. If the model is clinker, it will have to be planked keel to sheer and the seams should be set off: with a thin batten to ensure that thev appear as a fair curve from all angles. The planking will be found easier to fit if each plank is fitted in two or three pieces joined with butt straps. The planking seams should be glued, and planks fastened to frames and backbone with small brass screws, small brass nails such as are used for model railway work, or glued bamboo dowels. The latter may be obtained conveniently from split bamboo table mats but need a little sandpapering to make them round. A handy glue for this type of work is Cascamite One Shot . Resin Glue. Any surplus should be wiped off with a damp rag before it sets as chipping dry glue off obechi will pull pieces out of the wood. With the planking finished, the rest of the hull is fairly straightforward. Hatches, bulwarks, etc., 527 1964 should adhere to scale as any clumsiness will the appearance of the model. The plywood should be good quality exterior grade or, better marine ply, and in any case, should have the mar used still, end grain well sealed with paint or glue. The backbone could, of course, be made from solid wood as the original. This would involve more work but would remove the small risk of the backbone delaminating. No ferrous metal should be used anywhere as it will rust eventually and, if the model is sailed on salt water, in a very short time. Paint serves two purposes, appearance and protection. Gloss paint is the last thing to use on this type of model. Matt or eggshell finish will be much more realistic. It is worth applying a good yacht primer to a sailing model. It fills the rather open grain of obechi and prevents it from soaking up water. Two coats of primer, three coats of matt, exterior give adequate protection. followed quality by two paint or should Ballast may be lead blocks, well screwed down to the keel, although if stout boxes are fitted, some of it could be made removable for ease of transport. The important thing is not to allow it to shift if the model is heeled on to her beam ends by a squall. A mixture of glue and lead shot could be used to fill odd corners to save having to use shaped blocks. As regards the rig and fittings, concessions to convenience must be made unless the choice is a lugger whose rigging and gear is extremely simple. However, enough standing rigging should be left for the sake of appearance. The mast could be stepped on a coil spring, the rigging being hooked on to the hull when the spring is compressed. Releasing the mast then tightens the rigging. The spars can be made of hemlock, which is light, strong and fairly readily obtainable from most timber yards. Sails may be made from 2 oz. cotton sailcloth or from cloth from model suppliers. If the model is of a lugger having a large foresail and mizzen, it is worth making a set of smaller sails as well to save reefing on blustery days. Rigging may be fishing line and hemp line in various sizes such as builders’ chalk line, dyed if necessary. It does not matter about exact size as long as the various parts of the rigging are in proportion. Blocks are very tedious to make but some are necessary for realism, although the numbers may be cut down considerably. Unless the model is to a very large scale, the smaller fittings are best left off, though on a working craft the gear is very robust and rough and ready, which simplifies the modeller’s task. This may seem to gloss over an involved subject, but so much depends on the particular model and sailing conditions, and the patience of the modeller. Also, there are manv books on ship models which describe adequately the deck fittings and rigging. It can be seen that the building of a model of one of these craft can involve much reading and research before the model is complete. This can be interesting in itself but, in any case, the pleasure of seeing a miniature ship under way will be reward enough. Bibliography “Merchant Schooners’’, Vols. I & II, Basil Greenhill. “Sailing Drifters’, E. J. March. “Sailing Trawlers’, E. J. March. “The Fishing Luggers of Hastings’, J. Hornell. “Sailing Barges’, F. G. G. Carr.

Learn the basics of vane operation and improve that small sailing model with this Ulira-simple Vane Gear By ANY small sailing models are handicapped by poor steering and so often one sees them thrash- ing away on the inevitable reach. This simple little vane gear should increase the capabilities of most little boats. Simplicity, lightweight and, above all, balance are the main requirements for success, and care must be taken to ensure that the mechanism is as frictionless as possible. It is also important that the completed assembly should be to correct scale for the boat. The one described is suitable for boats of about 20 in. length; it is the one used on Minnow, last month’s full-size plan. The governing factors are the size of the rudder and its relation in area to the vane (about 4% is a fair figure to go on) and there should be enough room to allow the vane to be turned through 360 deg. without fouling the end of the boom. The plastic gear wheels serve a dual purpose: firstly as a reduction gear and secondly as a method of setting the vane angle. The ones chosen had a ratio of 2:1. These gears are brass bushed and can be fixed to the spindles by the grub screws provided. The spindle carrying the larger of the two gears forms the rudder stock, whilst the other supports the smaller gear and the vane. The vane spindle is housed in a brass tube, blocked off at its lower end to form a bearing. The rudder spindle passes through a brass tube in the boat in the normal fashion of a rudder tube and the bearing for this spindle is a small heel-plate let into the skeg. VANE FEATHER ALUMINIUM DISCS SOLDER TO GEAR BUSH ER og GOUNT VANE ARM =3) 20-TOOTH GEAR CENTRING ELASTIC NYLON 10-TOOTH VANE SPINDLE —er || VA NE Tech {i zt PLUG \ Both the spindles and their tubes are short lengths of brass tubing. Choose a gauge for the spindles which will fit the gear bushes (14 s.w.g.). The piece of larger diameter will be a free sliding fit over this. The spindles have small plugs sweated into their ends which are filed to points to provide bearings. These can be cut from the same piece of brass wire you will need for the vane assembly. The vane tube will also have to be plugged, but any small piece of scrap brass may be filed up for this, I suggest using part of a brass screw or hook. A certain amount of simple soldering is required, but, if you have not the facilities for this you might stick everything with Cataloy glass fibre resin mixture. This bonds wood and metal admirably. Start operations by fitting the rudder tube. Drill the hole through the hull and fix in position with a fillet of Cataloy resin top and bottom. This will have the added advantage of making the joints waterproof. Next prepare the spindles by sweating in the plugs and filing and grinding to a blunt point when cool. Leave the spindles long for the time being. The other tube for the vane gudgeon can now be made. This will need the plug of scrap brass sweated in. Drill down the tube into the brass plug just sufficiently to make a nice bearing for the gudgeon point. Locate this tube in the hull by placing the rudder spindle in its tube and thread on the larger of the two gear wheels. Mesh the gears and prick through the bush of the smaller. A small steel knitting needle can be used for this. Taking this mark as a centre, drill the hole in the deck; press the tube into hull until it reaches the keel and then cut off, slightly above deck level. We can now thread the smaller gear on to its spindle, place in its tube and test the meshing of the gears. Any binding or sloppiness must be remedied by adjusting the position of the vane spindle tube by easing out the hole with a fine rat-tail file. With the gears meshing well fix the tube in position with resin as before. Make sure here. SPINOLES RUDDER | pe TUBE H f Draper _ the tube is vertical by sighting: the rudder spindle or a knitting needle inserted in the tube will aid you i || F. FROM TUBE PLUGGED AT BOTTOM AND FILED Before turning our attention to the rudder blade and vane feather, the spindles can be cut off to length; watch the meshing of the gears and position of the bottom end of the rudder spindle. Whilst attending to this, we can also fix the position of the little brass heel, cutting a small slot in the skeg to take it. This little brass plate should have a slight indentation drilled on its face as a bearing for the rudder spindle. This brass heel cannot be fixed until the rudder assembly is finally shipped, so put it in .a safe place. 540

NOVEMBER Cut the rudder from ;); in. marine ply and groove the leading edge before fixing to the spindle with Cataloy resin. Whilst the rudder is setting —a warm temperature helps drying — bend up the brass wire for the vane arm, and make the feather from a piece of ; in. sheet balsa, sanding to a stream-line section and finishing with clear dope. The counter-balance weight is cast by drilling a *; in. hole in a piece of scrap wood, and pouring in the molten lead with the crimped-over end of the arm inserted in the hole. To assemble the vane, cut or file a notch across the face of the bush, and solder the brass wire arm into it. The balsa feather can have the wire loop let into it and secured with Cataloy resin; put a smear on either side and reinforce with small alloy discs. Finish the assembly by cleaning up the rudder, and finally locate by gluing the little brass heel in its slot. Paint the rudder blade, and when dry we are ready to line up the assembly and balance. Assemble the mechanism with the gears meshed and the rudder locked amidships—a clothes peg helps here. With the grub screw in the larger gear slackened off, line up the vane fore and aft so that it is parallel with the rudder and then tighten up the screw again. Place the model in a bath of water and heel it. File the lead weight until the whole system balances with the vane arm and rudder remaining amidships. This method ensures that the buoyancy of the rudder blade is taken into account. The construction is completed by arranging for a light centring line. For this, either solder a tiny hook to the top of the larger gear wheel or alternatively drill a ; in. hole through it exactly opposite the point where the gears mesh when the system is lined up fore and aft. Thread on one strand of rubber stripped from a piece of elastic and attach to an eye placed in the deck. The object of this is merely to give the rudder a tendency to return to the neutral position. The rubber should be only PERIOD SHIP [Continued from page 530] also permits the design to be visible from the rear. There is little rigging and only the one pair of shrouds. The latter may be built up on the model or made separately and transferred to the model. The verticals and horizontals may be tied or simply joined with a fast drying adhesive. tight enough to do Radio Control Equipment Electric Motors gears have 10 and 20 teeth, it is therefore possible to set the vane feather to steer nine different points of the compass — four on each tack and a dead run. If one starts with the vane feather lined up fore and aft, and then moves it to the next tooth, it will give a vane anglet for a beat to windward. Moving on one tooth at a time, MENTION “MODEL MAKER” one finds settings for the various reaching courses until the vane has passed through to 180 deg. and is set for a run —remembering always that the sail has to be gradually freed off as you move from the beat to windward to the run before the wind. Only by experimenting with each individual boat can one arrive at the best combination of sail and vane settings. I suggest you start by trying a dead run. Let the main sail out so that it is almost touching the shrouds and slacken the fore sail off as well. Set the vane feather so that it is pointing down wind — the counter balance arm will then be pointing dead aft. Let her sail off —and bon voyage. 7+This gives a vane angle of 36 deg. for a beat. Quoting H. E, Andrews’ article on Sailing Model Yachts in ‘‘Model Maker Manual 1957’: ‘“* . . . the true wind is blowing at 12 m.p.h, and the yacht’s speed to windward is estimated to be 3 m.p.h, Here the resultant . . . angle is 36 deg. ofl the starboard bow. Allowing same angle of leeway (2 deg.) the vane feather should be trimmed 36 deg. — 2 deg. = 34 deg. for a true course of 45 deg, … Colour Scheme Entire model is finished in a medium shade of varnish with the exception of the following areas: Raised edging to castles and patternwork on fight- ing top are finished in a light shade of varnish. Cross at mast-head is silver. Shields around castles as detailed on plan. Sail and flag on after-castle as detailed on plan. Send 2/6d. P/O for our Marine Catalogue 31 PRESTON NEW ROAD BLACKBURN MARINE FITTINGS AND ACCESSORIES ALL IN STOCK KINDLY will It is impossible to give a comprehensive explanation of vane gear operation in a few’ words, but briefly, one has to ensure that the vane feather is streaming down wind with the model correctly trimmed on its determined course. Actually the vane will point a little nearer the course of the boat, due to the boat’s own slipstream. To operate the gear one has, therefore, to be able to change the angle of the vane in relation to the rudder. With this little gear, all one has to do is to disengage the gears by lifting the vane arm, revolve the vane to the required angle, and replace. In the example being described, the respective Model Boats and Aircraft Kits by all leading manufacturers Glo-Plug Engines Greater – tightness prevent the wind from working the vane. RAWCLIFFE’S (CRAFTS) LTD. Diesel Engines this. 1964 WHEN Telephone: REPLYING TO – LANCS 57657 ADVERTISEMENTS