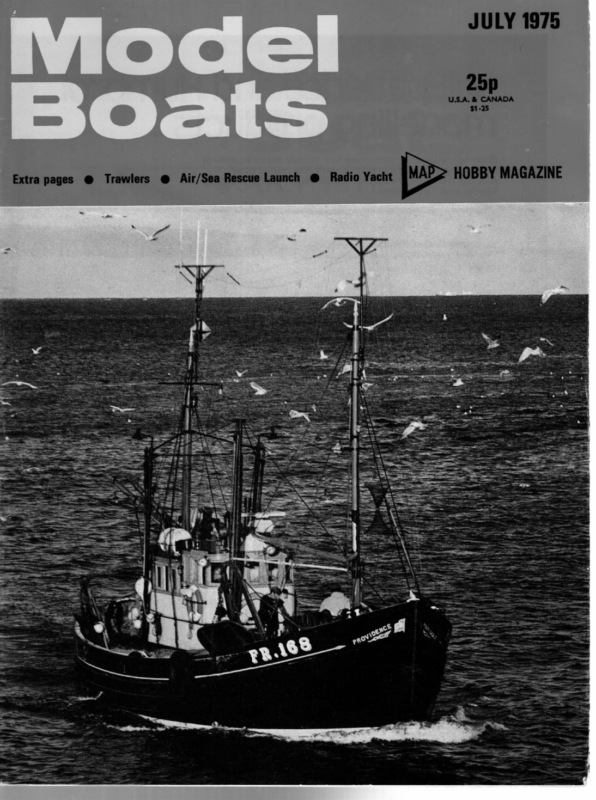

JULY 1975 25p U.S.A. & CANADA $1-25 Extra pages @ Trawlers @ Ajir/Sea Rescue Launch @ Radio Yacht HOBBY MAGAZINE

JULY 1975 In the Tideway HERE is little doubt that the BBC ‘‘Model World’ series, which finished in mid-June, created enormous satisfaction among modellers and a surprising degree of interest for non-modellers, judging from comment we have heard from many quarters. If you missed any of the (———uTgWqBdl 9xo‘.sS[pUaOIejIRyOAJe1Lo.YWMUuL&JdUYL,V0.O‘yWsAJT(“]TrESqA[o}sqISPaSPVI}ISevBDDIBMnl[yOnJOjN‘OgpRYOoY&puyLtEUU1YAUiWMRPI1TNAeSBs4MoS[lI9Dd}9I]jnpd4O}su)JoUtaYRvS.S1x}0tPpNAXJj,TIYdaPNiO0ljJa[OdUjpEAenO|ese9oyDAvpqLSy}SBq}YMUAj0ll1usYUnaS0IO9&J)[IIpd3b1p}diiuNed‘3v.bsavniSWkoDqyUoeu}BY,JOUOJjsA4MUep‘SeTIBlaSyp-~IJsptu98SaLm4onEiOdr}dqd‘y.c“Msp‘UuA3[0YurDeNoQqu}|ueY)]lgwRvoJiWpriTjUOoxolaJMU4aaSg8Od“IJ00yP[M|so]qPe,Dji33BenJSJyvHeOu}oYErU&390}oI1d.}41yvpA}XIduNn0[yW,IJ]0o0BOiiIV‘NsjooYr]a]9ueDea9}3rAJ‘edMv2[)OsB0S“d4p‘Iwd.U9UTUO0‘u}BYNAqO1WosuYYk,AS“Maie]mpY[}rd9VHIstSrJOypBxPfJPBaOjpUZAUB[U{sLaTMS1B0WF|[pIeo4NtSeYuoSIV]t}Udd9JO4}qP}OH|A9A0I4{PLU«BSTM[[RNSIA0lMQgP“nqBay‘j“39x9IeOoNYWJe1Y,4oPS}pT]KO}Bs “SUOTIIP ‘s ejo OY} NU, ‘s e[9 OEE e4jJO9/F HX pSUUMIOT‘OaU0)uduPTLIe6OTxs9aJ[OAyqNi,NUqo0keA1sYp}eMu9OopNIsaL41i}U‘y]SM[nUpY&Y yOoDJyEgjUpeosw‘ueBryOo} ‘oweUs iyjeoOqQsMPoyed“Y.4Ja/]“I9AWMOHJPploa AI9PoOs“9OURLIJ9d TAGOW SLVOd

JULY 1975 Right, the finished wooden plug, which splits along its centre line as shown in the lower photo, for my “‘ideal’’ design. These were based on my own experiences, and watching other boats in competition. They are listed as follows; I might add the list is not in any order of importance or preference. 1. Spade rudder. 2. Easily replaceable fin/keels. 3. Replaceable rudder. 4. Two or more complete rigs of differing aspect. 5. Acceptable appearance. 6. Radio equipment of proven reliability, switchable crystals on as many frequencies as cost will allow. Minimum of three control channels. : 7. A hull design that will “‘plane” in the right conditions. 8. A design that will lend itself to glass fibre con- 9. struction. Robust construction that will stand up to continual use without need for continual maintenance. 10. Weight around 194 lbs. in sailing trim with heaviest keel fitted. Dealing with each of these points in turn, I would comment as follows ;— 1. The use of a spade rudder in radio Marbleheads has now become almost universal, and an overwhelming number of boats have either been built with it, or the design has been altered to take advantage of the lower power needed to operate, making it possible to use the small aircraft type servos normally supplied commercially. This type of rudder makes the boat much more alternative weights and draughts of keel gives, in my opinion, a considerable advantage over other com_petitors who cannot so alter their boat. In windy conditions, a heavy keel, well down in the water, or in light airs, a lighter shallower keel will be of considerable advantage. 2. With the rules allowing keels, fins, and rudders to be changed at the commencement of an event, the use of simple job to change for a different area or aspect ratio. | Experience will show the best size for particular con- manoeuvrable. 3. Spade rudders by reason of their design are a Full-size copies of the drawing below are available ref. MM 1205 price 90p inc. VAT and post, from Model Maker Plans Service, P.O. Box 35, Hemel Hempstead, Herts. HP1 1EE. Hull is shown full-size (50in.) but construction must be based on sections and is not therefore suitable for the average beginner. ELECTRA ae aN J “my CRJeffries.& \ prsuthltige’, XiI_ | }/ 7 ~ (mm \ (1205 / J )|/, The, Model Maker Pans = Sh DIMENSIONS RIG & -SAiL_ STO ASPECT A= GO” B= 17° 4276″ B= ZO \ \ \ SS \ N\ were a \ : – ’) O= 56″ R= I2S* R= 10 = S10+2859= 796sqin = S10+280 RIG.C ~ STORM SuIT 509-878 oe ; HEIGHT HT OF OF ie stay . aegis’ y 05″ = P20sqi A= 455° B= IS*Q = 355° R= 95″—= 3425+ 168.62= — ; G2 455″ RIG.B – HIGH ASPECT. 6251S” C= 375° S\ 10) 4) SY ji — a FAIR WEATHER KEEL wr 618s ROUGH WEATHER KEEL wr — 10L8S |) | HATCH FOR ACCESS TO | RUDDER LINK HEIGHT: OF Jie Ne ; ° J

MODEL BOATS First hull out of the mould, with the mould halves and, beneath, the built-up deck assembly used as a plug. The standard sails on the Soling are of unusuall y low aspect ratio, and I feel this may well have been the reason they are so fitted. 6. There has been much discussion as to how much a radio Marblehead should weigh. My original Bewitched weighed 23 Ibs., its designed weight. I made another Marblehead recently that weighed 134 Ibs. all up. The heavyweight was slow to accelerate in light airs, but once underway, would coast around buoys and whilst chang- ing tack. The lightweight would accelerate in light airs, but as soon as the wind dropped, it stopped. After ditions. Two or even three are well worth making and taking to the pondside. 4. It has always been possible to change sail area and aspect, but I feel it worthwhile to make two or more complete rigs, and to be able to change the whole assembly quickly when weather conditions demand. I now havea standard aspect rig, a high aspect rig for conditions when the wind drops, and a storm set, having a very low aspect, and a decrease in overall sail area. 5. The majority of Marblehead designs are functional without in any way resembling a full size craft. My Soling was one of the few exceptions, and closely resembles the full size comment version. at the This has pondside. caused However, much favourable there are funda- mental faults in the design which I decided to correct, by fitting a bulb type keel, and modifying the hull profile to give greater buoyancy and make the hull plane better. I had tried high aspect sails on the Soling, and the boat kept dipping its bow into the water and stopping dead. watching many boats performing in all types of conditions, I feel a compromise weight of about 19 to 20 Iks. to be the target to aim for. 7, 8, & 9. It goes without saying that the radio equipment should be as reliable as it is possible to make it, and furthermore, should be protected from possibili ty of damp, which is I am sure a main source of many radio problems. Two control channels are a must, and I now prefer to have a third channel so that in addition to the control of rudder and sails, I have a chance to adjust the trim of the jib whilst actually sailing. The rudder control must be proportional. The winch in my opinion also should be proportional, but there are those who prefer a positional adjustment of the sail winch. The Jib trim again I feel should be proportional. The M.Y.A. rule book advises the use of two frequencies and recommends three if possible. This is a help, but with the ever increasing numbers of competitors at meetings nowadays, I feel it is becoming necessary to have more than two. There is no reason other than cost why all six standard colours should not be included. A point to remember is that the frequency switch should be immediately accessible on both boat and transmitter. One well known commercial equipme nt now on the market is advertised as having switchab le crystals; the switch is mounted on the printed circuit, and a screwdriver is necessary to remove the back of the transmitter case to get at it! The question of the design of a suitable hull for a radio boat poses problems not found in those intended for vane control. A vane boat must be directionally stable, and rely on the tiny power available from the vane to keep it on the predetermined course. Our radio boat must be easily manoeuvrable, and have a good perform ance on all points of sailing. Also its shape must in my opinion be suitable for fabrication in glass fibre. There is no perfect design, just that some are better than others. Most of its time, the hull will perform as a displacement boat, but given the right conditions, the design must be such as to permit it to plane when the wind is suitable. Just being able to plane is not enough, as it must also be completely controllable whilst planing. I think the appearance of the boat is importan t; the saying that “‘if it looks right, it must be right”’ I think is important. My Soling, which is a scale model of a fullsized craft, is a good example that proves that it is not impossible to make a design that is a near replica of a full-sized craft, and yet have a most acceptab le performance. The construction of the hull, fittings and rig must be robust. This does not mean it must be heavy and clumsy. It is important that the boat does not require constant service and attention. It should be possible to sail the entire season without having to do any major maintenance. The skipper who breaks a sheet during an important race has only himself to blame if he is still using Underside view of the finished glass hull and two fin assemblies of different weights and draughts. 338

JULY 1975 The finished hull & deck ready for bonding together. Semi-scale appearance is unusual for a racing model. last year’s sheets. The rule is to go over every part of the boat and its equipment during the winter, and check, and check again that everything is as near perfect as you know how. Only by doing this will you stand a chance of becoming a top skipper. At almost every meeting, I have seen boats go out of control, just because some silly little detail has been overlooked. That aerial plug that keeps falling out. Well, it shouldn’t ever fall out, or if it does once, take good care that it never happens again. Again, we have all seen the boat that fails halfway through an event, with the skipper bemoaning that his batteries are run down. If he is on dry batteries, he should carry a spare set at all times. If rechargeable, he should take good care that he hasn’t forgotten to recharge them. I don’t want to boast, but my boat has sailed every week-end through the last season without having needed any maintenance whatever. I broke a shroud at the Nationals at Guildford, and that was all the boat needed except for cleaning and wiping down after every outing. The homemade digital radio had no attention over the past two years, and I am not planning to do anything to it before the start of the new season. I see the batteries are kept up to charge, and rely on careful construction and keeping it dry. Given all the factors that in my opinion should make the ideal boat, I feel I have gone a long way towards this goal. I have mentioned the excellent performance of the Soling under certain conditions; if I could overcome the weaknesses, the result should be very satisfying. As mentioned previously, if I stop the tendency to dig in, and improve the balance by fitting a different design of keel, I should have a boat that should prove to have the performance I am looking for. The digging in tendency I have stopped by making the hull have more buoyancy “up front”, and with detachable bulb keels, of differing weight and draught, I can select the one best suited to the prevailing conditions, and fit it in a matter of minutes. Sailing in my club is one of the German Klug Ghiblis, and I was particularly impressed with its design. I liked the rounded upperworks of the hull, and decided to copy this. In this I had anticipated Vic Smeed’s article in Model Boats December 1974 on building rounded hulls. This type of construction makes for a simple method of moulding in fibre glass, makes a stiff hull that reduces windage, and finally makes for a shape that enables me to make a moulded deck assembly. Having settled on my requirements, I started by drawing out accurately the sections taken at 4” centres. I based the underwater profile on the Soling, added 1” to the overall beam, and significantly increased the buoyancy over the first sections. I let several fellow club members see my efforts, and as their comments were all favourable, I decided to proceed. I drew out all the sections exactly to scale, and commenced construction by making a split plug suitable for making a glass fibre mould. I spent a lot of time on this wooden plug. Not only getting the shape right, but painting it, rubbing down and repainting until I had the finished surface as smooth and polished as I could get it. My aim was to get the best finish as I could on the plug which would save much time on polishing the mould. I then passed the plug over to a friend who is an expert in handling fibreglass for him to make me the mould. He had completed the laying on of the gel coat and building up the necessary thickness of reinforced glass fibre when disaster happened. On removing the mould from the The completed model looks a little bulkier than many RMs, but it obviously has potential — 5th in its first major race. 339 wood plug, the paint I had so carefully applied had pulled up, and what a mess, the trouble was easily seen. I had started painting with wood primer, went on to wood undercoat, and then when I had a fair finish I changed to polyurethane. Then when the gel coat had been applied there was a chemical reaction between the assorted paints. The result was the perfect finish I had hoped for resembled a crazy paving patio! One’s first reaction was to scrap the lot and start again. I thought of all the time I had spent on the plug, and the cost of all the resin and fibreglass. I started to rub the mould down with “‘wet and dry” paper. Something like a full week’s work went into each half of the mould, until I had rubbed the whole lot down to a surface that was far from perfect, but that would produce a hull of the shape I wanted, but one that I would have to paint to get an acceptable finish. The two halves of the mould went back to the expert, and a few days later he supplied me with a bright shiny hull cast in a bright orange; how he was able to impart the finish on the moulds to get this finish, I did not enquire. Sufficient to say I was delighted with the finished product. In this little tale there is a moral for anyone trying to make a wooden plug. Start with polyurethane, and don’t use anything else. (to be continued)

MODEL BOATS Simple Yachting Sailing with rudder-only control and a very easy non-self-tacking vane gear. Both in response to requests. Wie the number of non-class (usually semi-scale) kitted yachts now available it is inevitable that we should have quite a number of queries in respect of single-function radio control, especially as many begin- ners with no knowledge of sailing regard normal two- function sail and rudder control as either expensive or complex. Quite a few of them are in possessio n of serviceable single-channel equipment, often ex-aircraf t, and are interested in fun-sailing in areas where engine noise could cause problems. So if the more advanced will excuse us, we’ll briefly repeat ourselves. A yacht can be sailed on rudder-only control quite well, but not as well as if the sails can be adjuste d— assuming that the controller is getting the adjustmen ts right, of course! The reason is that a sailing model can be sailing in any direction except within about 40 deg. of the wind, i.e. 360 minus 80, or, since it sails on either tack, 180 minus 40=140 degs., and there is an optimum Position for the sails on any heading. The sail movement on one tack is near enough 90 deg., so that ideally 1 deg. change of course requires an average about .65 deg. change of sail angle. No-one gets as close as this, but a top skipper won’t be more than two or three degrees out. Without sail control, the desired course cannot be sailed without using the rudder, and applying the rudder creates drag which slows the boat. By skilled sail-setti ng the effect can be minimised, but on the whole the boat will only be achieving its maximum performance on the one heading where the sail angle happens to be right. However, for fun sailing a compromise setting, usually about 15 deg. boom angle, will allow the boat to be sailed under control, reasonably respectably, within the 140 deg. segment (on either tack) mentioned, and this means that it can be sailed on, say, a reed-surrounded pool and brought back to the starting point, a considera ble advantage, of course. A sailing model offers the benefit of interference-free single channel operation; quite a lot of such gear was intended for i.c. engined aircraft, and suffers from bad interference if installed in an electric-powered boat. On the other hand, single-channel equipment can weigh only 6-7 ounces, sometimes even less, so that control of quite a small yacht is possible. As an example, the little model in the photographs, less than 20 in. long, sails of this mechanism, the limitation imposed by the number of teeth on the gear. A 60-tooth gear must move in “steps” of six degrees, or in other words the fineness of course setting depends on how many teeth there are on the gears, and there is obviously a practical limit. If we fit a friction arm on the second gear, adjustme nt becomes infinite, and we can scratch and paint some marks on the gear to give approximate guidance for repeating settings. The arm can be carried forward and a counterbalance weight fitted. This leaves us with a certain amount of friction which can be reduced by allowing the second gear (which turns on a brass pin or rod fixed into the deck) to rest on a stub of tube VANE FEATHER very well; it was built by car enthusiast Gordon Tapsell and photographed sailing on the Thames by Alec Gee. Note the polythene-wrapped receiver and drip-proo f radio box, incidentally. The crunch usually comes when someone else turns up with a similar yacht and you want to see which goes fastest. Sail control starts to look very attractive! Basic Vane The very simple two-gearwheel vane first used by Geoff Draper has been fitted to some hundreds of smail models with excellent results. A snag arises when model size is increased in that the vane and arm get heavier and really require counterbalancing. In overcoming this problem we can also eliminate the other minor drawback 350 ADJUSTABLE WEIGHT RUDDER SHAFT

JULY 1975 studding (screwed rod) is epoxied into a drilled hole and a weight, which could be several washers, is trapped between two nuts and can be adjusted fore or aft to achieve balance. True balance, incidentally, takes account of the buoyancy of the rudder when the yacht is heeled! For travel to and from the lake, it is safest to slack off the pinch-bolt and lift the arm-plus-vane off altogether. The only points to watch are that the gear teeth mesh adequately but freely, and the vane feather clears the backstay(s) when swung forward. A shirring elastic centring line is needed to exert a light pull tending to centre the rudder, and the feather needs to be upright; it can be raked, but not leaning drunkenly to one side. chamfered to a knife-edge. The mechanism is still not of the self-tacking type, but apart from this will provide complete control. The arm needs to be hardwood or plastic, wide enough to be drilled to fit over the gear boss (4 in. dia. on the usual Ripmax nylon gears) and deep enough to accommodate an 8 or 6BA bolt. A sawcut is made from the vane feather end up to and just past the boss hole, and the extreme end opened up with a file etc. to accept the balsa vane feather, which can be cemented and/or pinned in. The 8 or 6BA bolt, just abaft the boss hole, tightens the arm on the boss so that it can be rotated but will not slip in a gust. At the front, a long bolt or length of DEEP SEA FISHERIES (continued from gage 332) The Herring and its Fisheries de Caux. The Listener 26.8.1936. King Herring The Herring and its Fishery W. C. Hodgson. Fishing News (Books) Ltd. The Lemon Sole through the patent roller fairlead in the bulwarks. The arrangement of the dinghy looks rather odd but it was so arranged to keep the bulwarks clear for the trawl beam which had to be stored along the side. If the dinghy was required it was manhandled; as one old fisherman put it—“‘If we wanted to use the boat we just chucked the Drawings Sailing Drifters E. J. March. Sailing Trawlers E. J. March. Inshore Craft, 2 vols. E. J. March. The End of the Road Peter Norton. All the above contain drawings of various sailing fishing craft. b….y thing over the side!’’ To recover it the mizzen gaff was used as a derrick. The Hermes was built in 1893 by Alexander Hall & Co. of Aberdeen for the Anglo-Norwegian Steam Fishing Co. Ltd. of Hull to the registered dimensions of 104’ x 20’ 6” x 7’ 9’ dr. forward, 11’ 3” aft. She achieved 104 kts. on her trials. At #” = 1’ the model is 28” long by 5}” beam and with a mean draught of 24” has a calculated Subject of the plan – trawler Hermes The Hermes represents the second stage in the development of the steam trawler, if one ignores the paddle trawler which was only a temporary phase. The first steam screw trawlers were just larger, cut down versions of the sailing trawler. These had iron hulls and were fully rigged except that topsails were omitted. There was only a small superstructure over the engine and boiler and they were steered from right aft. In the Hermes we see the distinctive outline of the steam trawler, as we know it, beginning to emerge. Most of her contemporaries had the bridge aft on the casing just in front of the mainmast, displacement weight of 6 Ibs. Colour scheme Hull Boot-topping Funnel Superstructure but the Hermes has progressed just that little bit by having her bridge forward of the funnel. The deck is flush at the bow; although raised forecastles were introduced shortly after 1900 many small trawlers were still built with an open foredeck even in the 1930s. The beam trawl Dinghy is still in use so the trawl winch has only one barrel, there is only one diverter bollard, and the warp leads Black with white trim line along bulwarks. Red. Black with red five pointed star. Brown (teak). The early boats often had the superstructure grained to represent wooden panels. Black. Davits Masts White. Black, but mizzen is white up to a Ironwork on deck funnel. Black. point level with the top of the CARDELLA (continued from page 335) of the test. This led me to believe that I had been a bit pessimistic about air supply to the stoke-hold! All set now for a trial on water, so off to the nearest boating lake. Alas, on arrival, it was only to find that someone had pulled the plug out, and I was confronted with an acre of nice dry concrete! So off to Newquay, where I was surrounded by about fifty hungry tame ducks and a very belligerent swan who was plainly a conservationist. Added to which, three bus-loads of O.A.P.s arrived to feed the ducks, so I called it a day. Third time lucky, however, and with the safety-valve lifting, Cardella was launched with a bit of port rudder, and off she went. Too much rudder on the first run, and she continued in tight circles for ten minutes, heeling like a destroyer on steering trials, despite her modest rate of knots. The next trip was a great improvement, sailing in wide circles on an even keel, but around twelve minutes was all the boiler could manage under load, with ample water left. She took in no water at all in the hull, despite the fact that the propeller-tube is plain and unswaged, but I had taken the precaution of soldering a snaptop oil-cup on the inboard end, and topped it up before each trip. I now feel satisfied that a cardboard steamship is a quite feasible proposition. if reasonable precautions are taken. Cardella is certainly no beauty, and would cause Mr. Jim King and his fellow experts a good deal of pain, I fear. Gratings and vents appear in improbable places for purely functional reasons, she is unrealistic below the waterline and pretty stark above it. I have so far avoided fitting rails and other likely obstructions to getting the lamp out in a hurry in emergency. But, power plant apart, she cost less than £1 to build, and although I know that the experts look down their noses at the humble oscillating engine, at least mine has allowed me, after 70 years, to own a working steamboat! Radio Control If you wish to use radio control equipment you need a licence, but this involves no tests or other compli- Licences cations. Model control transmitting licences are £1.50 and last for 5 years. Applications or renewals are dealt with at The Home Office, Waterloo Bridge House, Waterloo Road, London SE1 8UA. 351 ann

MODEL BOATS Midland District 10Rater Championship, Bournville, 18th May 1975. Notes by Midland District Secretary. It was “‘one of those days” when the ten competitors assembled at the Bournville pondside for this usually popular event. The wind was extremely light and rather undecided in its direction which seemed to upset the visitors somewhat. There were mixed fortunes for the skippers in the earlier heats but once settled Pegasus, Kintaro, Cu Copper and Candida started to pull away from the remaining field and their scores at the lunch break were Pegasus 20, Kintaro 19 plus resail, Cu Copper 16 and Candida 16. After lunch the wind got lazy and nearly gave up but the sun came out to give some consolation. The wind situation led to some interesting “‘square dancing” while the boats made their way to the other end of the lake. Cleethorpes are fairly new to 10Raters and had mixed fortunes. Gordon Griffin sailed his new boat Electric Soup (Electric Soup design) and was doing quite well for first time racing. Roy Noble on the other hand was having an unusually disastrous day. Points were swopped back and forth with “cat’s whisker”’ wins battled for. A change in the wind turned many an advantage to a disadvantage—such is life! Candida had dropped a few points and fallen behind the three original leaders. The race ended some time after 5.00 pm with power boats taking over the pool and creating a fair amount of wash, so only the necessary resails were taken and the result, a win for Mike Harris, was justified, after some consistent sailing. Results: Kintaro Cu Copper Pegasus Poppet Candida Red Alert Electric Soup Flipper Lady Alice Elizabeth Rowena M. J. Harris H. Dovey K. Atherton Bournville Bournville Bournville 39 points + Resail 33 points 29 points V. Bellerson G., Griffin D. Warren Bournville Cleethorpes Wicksteed 24 points 18 points 14 points R. Noble J. Stowe Cleethorpes Bournville M. Dovey J. Beattie Bournville Birmingham 27 points 24 points + Resail 10 points 8 points 1975 ‘‘Nylet Trophy”’ The second year’s race for the “Nylet Trophy” was held at Setley Lake by the New Forest R/C MYC on Sunday 18th May. A total of twenty nine yachts was entered, believed to be a record attendance for any R/C yachting event in this country. The weather remained dull and cool, with little wind. Only at the conclusion of the event did the sun start to shine. In view of the light wind, and the fact that the schedule called for 29 races, a single lap of the course was used. Thanks to the excellent relations and co-operation that exist between the club and the Forestry Commission, a landing stage has been made, so that competitors can put their boats into the water and remove them without the necessity of wearing waders. The New Forest Club is fortunate in having a member who is a computer expert, and the racing schedule used was processed on a computer; each competitor was given a computer “‘read out” which showed him in which races he was to sail and the frequency he was to use. Sailing six boats per race, and a total of 29 races, called for a prompt start to each race to complete the schedule in time. Thanks to the work put in by the Racing Secretary, in sorting out the frequencies, only one instance of a frequency clash was experienced through the whole day. This was no fault of the schedules, as it was found that one competitor (nameless!) insisted he was on red, where the club monitor proved he was on yellow! On removing the back of his transmitter, he found his crystals were in the wrong sockets. His humble apologies were accepted, and as the trouble was found before the start of a race, he incurred no penalties. Members of the host club committee acted as race judges. The latest MYA racing rules were used, and the strong discipline shown by the judges was accepted by all competitors, and no instances of protest were recorded through the entire event. All transmitters, except those actually in use, were impounded, A new score board made by members of the club was used for the first time. This gave competitors and spectators alike a full report on how the event was progressing. An innovation used for the first time was that each competitor collected from the Control Point, at the start of each race, a clip to fit his transmitter aerial and a coloured pennant to clip on his masthead, the colours corresponding to the frequency he was using. This was a considerable success, and sae ap judges to clearly understand which boat was which. It has become a tradition of the New Forest Club to start events on time. This year, as competitors were ready, the racing started 15 minutes early! Racing continued without a break for either lunch or tea, and in spite of the light wind, the entire schedule was completed by 4.30 pm. An indication of how the reliability of yachts has improved was that at the conclusion, all yachts were still racing. There were no retirements. The standard of sailing was of a high order. Competitors had really made themselves aware of the racing rules, and there was some really exciting racing that thrilled competitors and spectators alike. At the conclusion of the event, Mr Frank Parsons Senr., Managing Director of Nylet Ltd., presented the Trophy to New Forest Member John Cleave, who sailed his boat Knut to become the outright winner. Awards were also made to J. Wild sailing Bloodhound who was second, third was T. Able sailing Moonraker, and fourth last year’s winner, N. Hatfield, sailing Troll. The remaining positions were: equal 5th C.R. Jeffries sailing Electra XII and D. Waugh sailing Teachers Pet, 7th J. Clark Aeolian and J. Foster Panic, 9th D. Stevenson Maybee and J. Ayles Jonda, 11th N. Curtis Bloodorange, 12th D. Robinson Pabrill and R. Gerrie Sea Witch, 14th D. Andrews Voom, 15th M. Colyer Delta, 16th J. Robertson Electra X and G. Coombs Red Wolf, 18th D. White Mistral, 19th M. Smerin Snoopy, 20th N. Oxlade Sunchine 11, 21st J. Curtis Frantica, 22nd A. Oxlade Lenora, 23rd J. Thomas Margaret T, 24th T. Godsall Bakers Dozen and J. Hill Falicity, 26th E. Andrews Teazle, 27th A. Wood Jildi, 28th A. Brown Sally Ann VII, 29th M. Oxlade Scimitar. Books and Catalogues A series of World War 2 ‘Fact Files” is published by Macdonald and Jane’s, London, and two which appeared a few weeks ago will be of interest to warship enthusiasts. British Escort Ships is a 64 page 10 in. x 8 in. listing of front-line Atlantic escort vessels, up to Loch and Castle classes, with hundreds of ships noted and photos of 80 of 354 them. American Gunboats & Minesweepers does a similar job on what were basically American escorts. Either costs £1.20 (card cover) or £2.10 hardback, and both are by H. T. Lenton. From Almark Publishing Co. Ltd., London, we received a book in the same general field, American