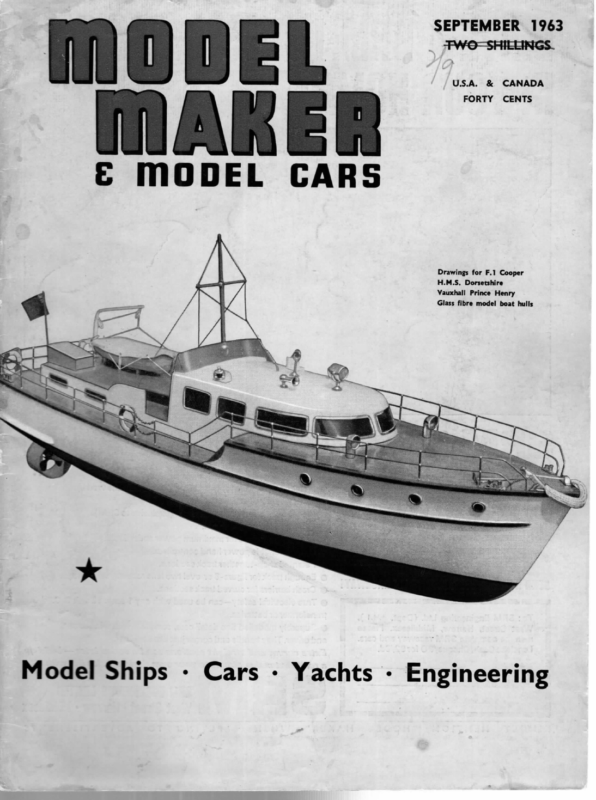

SEPTEMBER 1963 7FWCG-SHIELEINGS. U.S.A. & CANADA FORTY CENTS Drawings for F.1 Cooper H.M.S,. Dorsetshire Vauxhall Prince Henry Glass fibre model boat hulls Model Ships – Cars – Yachts – Engineering

SEPTEMBER] £963 GLASS FIBRE BOAT HULLS How to make a hull—by the winner of the 1963 10-rater championship (with yacht ‘Strider’ seen at right)—G. P. OLIVER if Ma article deals with model yacht construction, although the methods described could easily be adapted and applied to power boat hull construction. Glass fibre, or to give it its full title Glass Reinforced Plastic, has several advantages over wood as a material for building hulls. However, unless an existing hull is to be copied, it offers no easy solu- tion to the difficulty of construction. The two important things about a hull are its shape and its weight. Its shape must be correct with no hollows, etc., and the hull must be strong and rigid enough to keep this shape. On the other hand the hull must be as light as possible so that the proportion of weight in the keel keeping the boat upright is as large as possible. Glass fibre has a density of about twice that of normal woods. Thus for a hull of the same weight the glass fibre one must be half the thickness of the wood hull. Fortunately glass fibre is stronger than wood so this can be done safely. However, glass fibre is rather flexible, and to make the hull sufficiently rigid “ribs” must be added. As far as cost is concerned, the cost of the hull outside and it only has to keep its shape long enough to make the female mould from it. It is of course vital to get this shape perfect, as the copying process cannot “iron out” faults. compares favourably with the cost of wood but the cost of the mould has to be added to this. Male moulds can be made of any material, wood and plaster being the obvious choices. I used plaster, but would recommend the use of wood if enough is available. Plaster is probably a lot easier to get in the rough shape of the hull but is very difficult to shape into accurate three-dimensional curves. A plaster mould is easier in that hardboard sections can be built in and the plaster shaped For a 10 rater hull and mould the cost would be of the order of £7, depending on the exact method of construction chosen. Moulds There are two types of mould, male and female. The laminate is built round a male mould and inside a female mould. Thus an existing hull if used as a mould is a male mould. If a laminate was built round this hull it would obviously be the same shape as the hull but slightly larger. Besides being too large the outer surface is rough, and the mould cannot be: removed from inside this glass fibre laminate. However, the inner surface of the laminate will be a perfect female copy of the male mould. This laminate can therefore be used as a female mould if it can be removed from the male. To do this it is made in two halves which are joined down the centreline of the boat. This female mould could be made of plaster but this is not very satisfactory as it is bulky and easily damaged. correctly between these sections. This type of mould construction is discussed in the M.A.P. book “Glass- fibre for Amateurs”. Figures 1, 2 & 3 show the principles of plaster male mould construction. This is somewhat similar to the initial stages of planked hull construction. In this case hardboard sections are cut out and shaped to the full section as shown on the plans. Note that these sections do not stop at the deck-line but are continued to a datum level which is parallel to the waterline but clear of the deck. This level will be the surface of the building board. These sections must be the correct distance apart, usually 54 in., and must be held rigidly upright. The deckline is marked by a horizontal piece of hardboard which runs all the way round at the deck line, smooth side towards the hull, which will give a flange on the female glassfibre mould at deck level. To save plaster the mould is not made solid but is built Male Mould Although it is easier to start with an existing hull and copy it, this has the disadvantage that you are building a well-tried design. This may seem to be an advantage to a beginner but if you want to win about 2 to % in. thick over a framework of thin wire races you either have to copy the fastest boat or start from scratch with a new design. If you are lucky enough to be able to copy one of the top covered boats in a class all well and good, but there is little point in copying a well-tried second rate design which loses whether you sail it well or badly. Building a male mould from plans requires as much care as building a wooden hull. It probably requires less skill as one only has to worry about the with pieces of cloth to prevent the first layer of plaster falling through. When this first layer of plaster has hardened the framework is strong enough to take the weight of the rest of the plaster. This layer should be built up to, or above, the final shape of the mould. It is difficult to patch hollows with another layer of plaster as the joint is weak, so this laver of plaster must be thick enough to complete the job. Some attempt can be made to shape 435 MO

WODEL IMJA\KIEIR} HOLES FOR WIRE ae FRAMEWORK FIG.1 lose rubbing compound. Presumably polyurethane paint will stick to dry plaster and this could be used WIRE FRAMEWORK, to give an even better result than the cellulose. DECK Figure 1 shows the shape of a hardboard section. Fig. 2 shows part of the framework showing the LINE wires that support the plaster and Fig. 3 shows a section through the completed mould. bors FOR HARD&OARp MOULD EDGE SECTIONS ~OATUM LEVEL DECK LEVEL SHAPED AND PAINTED SURFACE PLASTICINE FIG.4 Seeepeae TIE KEEP SHARP CORNER AT DECK LEVEL VE\ r=.. ae TRIM HERE DECK PIECE OF : 7 THICKNESS HULL FLANGE FOR BOLTING TWO HALVES TOGETHER \ ~ font ON BOARD FEMALE MOULD 1 LAYER OF MAT HOLLOW GETWEEN SECTIONS WLLL) BUILDING Ye so. INWALE FIG.5 4g BELOW DECK LEVEL MAT MOULD WOOD FILLING HOLLOW AT KEEL JOINT MOULD JOINT the plaster as it is applied, using a flexible straight edge curved round the sections. This obviously saves some carving. As about 30 pounds of plaster are required, cheap builder’s plaster is used which is perfectly satisfactory. The plaster is scraped. Surformed and sanded down to its correct shape. Scraping is best done as soon as the plaster is firm, sanding should be done when it is dry. Drying may take a few weeks, depending on conditions, but the mould must be absolutely dry before any attempt to paint it is made. Hollows and faults can be filled with Polyfilla before painting. For painting I used two layers of Belco surface primer followed by a cellulose top coat. Cellulose putty can be used for any faults that may be spotted when rubbing down the primer. The top coat is finished with 400 wet or dry paper used wet, then polished with a cellu- Female Mould This is made round the male mould in two halves, using glassfibre. (The exact procedure of laminate construction will be discussed when dealing with the hull). The female mould is made of one layer of the thin surface mat followed by one layer of 12 oz. chopped strand mat. This gives a laminate slightly less than % in. thick, strong enough for any reasonable treatment. The mould is made one half at a time by constructing a plasticine ‘dam’ about 1 in. high down the length of the hull and building the first half up to this. When the glassfibre has set the plasticine is removed and the other half of the mould built up to the first half, not forgetting the release agent to prevent the two sticking together. This should give a joint at the centre, through which holes are drilled every few inches to take bolts to hold the two halves together during hull construction. These flanges also help to strengthen the mould and keep it in shape. When taking the mould off the male mould the plaster may be damaged but it is of no further use. Care should be taken during the construction of the two moulds to keep a sharp edge at the deck line, and not to round off the corner with polish or paint. The finished female mould should have a smooth inner surface that needs little attention. Figure 4 shows a section showing one half of the glassfibre mould and the plasticine dam. Hull Construction — Materials There are two main types of resin in use, Epoxy (Araldite) and Polyester. Epoxy resins are tougher and more water resistant but also more expensive. Polyester resin is perfectly adequate for model yachts which on the whole spend only a small proportion of their time in use, and do not get left at moorings, etc. Glassfibre material is of two types, mat and cloth, the mat being made up of short strands of glass, and the cloth being a woven material with thin-! ner strands running the length of the cioth. Cloth gives a stronger laminate for two reasons, one is that the strands are continuous and the other is that the laminate contains more glass in the same amount of resin. Glass cloth is also more useful as it is much thinner than mat. One snag is that it has poorer adhesion between the layers than a laminate built using layers of mat. However, the model yacht builder has no choice as even one layer of the thinnest (1 oz.) mat is slightly too heavy. For the hull of my 10 rater I used three layers of 9 thou. cloth. This uses about 4 lb. of resin per square yard. This amount of cloth gives a hull about 1 lb. too heavy, but the hull is strong and only needs extra strength round the keel area. The weight could be reduced to the same as a normal wood hull by using two layers and adding strips of mat as ribs where necessary. So far I have made three hulls, all using three layers, mainly because in these cases the owners thought the certainty of having sufficient strength was more important than having the extra weight in the keel. On a lighter design this would have 436 mattered more. However, I hope that the

SEPTEMBER next hull built from the layers of cloth. Another surface mat; this is a which is applied after the mould will use only two glassfibre material used is fine textured glass tissue first surface coat of resin. It is intended to strengthen the surface of the laminate and also to prevent the weave of the cloth showing in the surface. Pigments are available in standard colours which can be mixed to give any shade. This saves painting the hull, and if the pigment is used in the correct proportions for the first two layers of cloth, gives an excellent result. props from the other side (fig. 5). Resin wood glues will not stick to the glassfibre, so the glassfibre resin is used. This is satisfactory for this joint which has a large contact area, but this resin should not be used for wood to wood joints. Araldite will also adhere to the laminate. Deckbeams are fitted before taking the mould off the hull. When the deckbeams have set in, the mould can be taken off. The two sections are unbolted and pulled carefully away from the hull. They should part from the hull fairly easily if the parting agent was applied correctly. When clear the edges can be trimmed off the hull using a hacksaw and trimming to the deckline with a sharp plane. The plastic is rather brittle to drill or cut so this has to be done carefully to give a clean edge. Slight faults can be filed down and sanded with 240 wet or dry, finishing with a finer grade. The hull can be polished using the cellulose rubbing Construction It is essential that the surface of the mould is treated correctly, otherwise the laminate may stick to the mould and everything be spoilt. The clean mould is first polished. Some polishes have a disastrous effect on the resin and prevent it from setting. The polish recommended is Simoniz wax car polish of the older type without silicone. Give the mould two coats of this as per instructions. The mould then has to be treated with release agent which prevents the laminate sticking to the mould and enables it to be removed. There are two common types of release agent, and examples of each are Bondaglass Nos. 1 & 2. No 1 is a wax emulsion which is used on a wood or plaster mould whatever type of paint is used, and No. 2 is an compound, but it is a harder surface than paint so this takes longer. Using a large diameter polishing buff on an electric drill is the ideal solution. The hull can also be painted and as it does not absorb paint two coats of polyurethane are sufficient. Every trace of release agent must be removed before painting and this can be done by washing with detergent. A hole is cut for the skeg which should be continued up to the deck in the normal way. The skeg is also set in with the resin. A piece of wood is moulded in at the keel joint where the deadwood is on a planked hull. A layer of mat is set in over this area to help spread the load of the keel, and mat ribs are added where extra stiffness is required. In my hull alcohol based release agent which is used on glassfibre or metal moulds. Therefore use No. 1 on the male (plaster or wood) mould and No. 2 on the female glassfibre mould. When the release agent is dry the resin can be applied and this is done flowing it on with an ordinary brush, avoiding forming air bubbles. When the first layer of resin has set firm (thin layers set slowly therefore use more catalyst than usual) the layer of surface mat may be applied. This is the trickiest part of the job, as there must be no air pockets next to the surface. Surface mat is difficult to shape round a curve, but overlaps and joints do not show so the mat is applied in wide strips and cuts made if there is any danger of a fold. Shaping round a male shape is slightly easier than inside a female shape. Keep the brush full of resin to avoid dragging the mat, and do not mix too much resin at once as it is better to have to mix more batches than to have the contents of your bowl ‘gel’ solid before use. The next layer is cloth in the case of the hull, mat for the mould. Mat shapes quite easily but care must be taken to ensure that it is fully impregnated with resin. The cloth can be closed up but will not stretch, and so the best method is to lay it on top of the previous layer in one piece if possible, and carefully shape it round the curves and then brush on the resin. Be careful round the corner at the deckline as it is very easy to leave a slight air space here. Always lay up some extra over the edges as this ensures that the actual edge of the hull gets its full share of resin. Additions such as inwales and skeg should be moulded in as soon as possible using the resin. The resin sticks best to itself if not fully cured. Full curing takes several weeks, but the resin is hard within a very short time. Fitting Out Before fitting the inwales it is best to fit two ties across the top of the mould to keep everything in shape. 8% in. square timber is then shaped and fitted as inwales, one side at a time, using clamps and I had some strengthening beams from deadwood to inwales but I have since removed these. Keel bolt tubes are set in, the keel being made in the normal way. Repairs The only trouble, short of breaking the hull, will be scratches which prove awkward if self coloured resin has been used. Minor scratches can be polished until insignificant, and only exponents of the Fleetwood wall game are likely to suffer from major scratches. Brummer waterproof filler provides an effective if not artistic repair. Squashed bows can be avoided by flattening the point and using a metal bow piece, and adding slight glassfibre reinforcement on the inside. For a 10 rater or A class yacht, the glass fibre hull has little or no advantage over the well built wood hull, except possibly length of life. As far as construction is concerned it only offers a large advantage if more than one hull is to be built. In an M class yacht the radii of the hull curves are all smaller which is better for glassfibre as the tighter curve is more rigid, and worse for wood as it increases the stresses set up in the wood during construction. It may be that g!assfibre construction will be distinctly advantageous in this cless, a point which we hope to prove here at Birkenhead. Glassfibre is ideal for the experimenter with all sorts of variables to adjust. One possibility is the use of a thin layer of rigid polyurethane foam as part of the laminate to increase rigidity with very little increase in weight. I hope this article will encourage people who like to try new methods and not just the person who wants to run off a copy of someone else’s hull, though new boats are always welcome. In case any one does not know where to obtain materials there is a list of manufacturers in “Glass Fibre for Amateurs” and the firm I deal with are very helpful and keen to encourage the amateur. 437 SS 1963 ee |