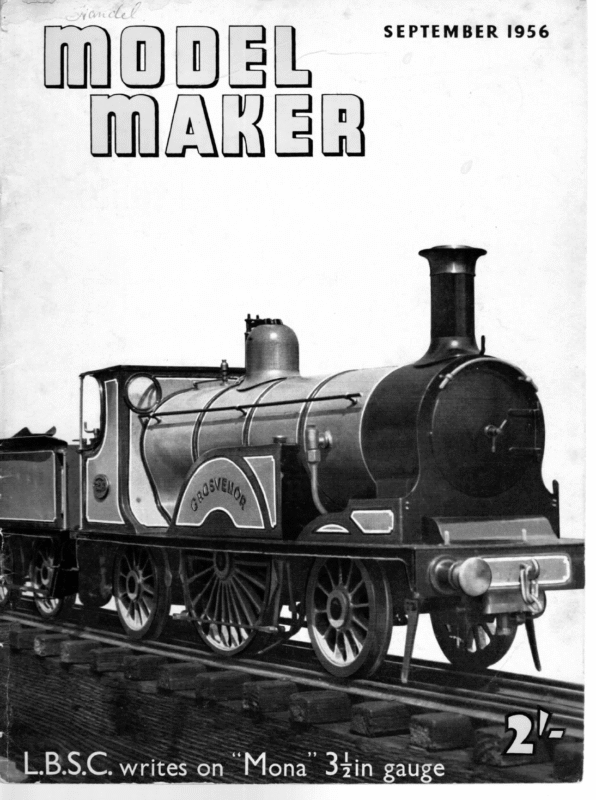

SEPTEMBER 1956 L.B.S.C. writes on Mona 3z2in gauge

MODEL Above: Winner Sirocco leads Estrellita. while two more boats EXTENSION of this year’s 10-rater Regatta — at Fleetwood to embrace a full week’s racing failed to attract the generous entry anticipated, and O. O. D. Mark Fairbrother and his staff had the unenviable task of stretch- prepare to come under the starter. ing a total of twelve boats to make four days’ racing. That he succeeded admirably in this difficult task was voiced by all competitors, who thoroughly enjoyed their sport, and quite failed to notice how frequently they came up against the same team. If quantity was missing, quality was much in evidence, and Sirocco entered by J. Lace, of the Birkenhead Club, proved a clear winner with 178 points to runner-up’s 155. Skipper was J. Palin, who has tried very hard in the past, assisted by R. Forshaw, a young Above: Flora and London boat Aegir, which came third. Below: Cordelia makes the running from Manx Rivington Lass. mate of considerable promise for the future. Design was by J. A. Lewis, whose Halceyon is a popular MopEL MAKER plan, a boat to whose lines placed second in last year’s event. John Lewis will be particularly pleased by this success since he has always been keenly interested in the 10-rater class and, as one of this country’s more advanced designers, has probably carried out more experiments with this type of model than anyone else. Weight of the winning boat is 33 1b. 140z., sail area 1,098 sq. in. and this is her first season’s running. Only two entries came from the south, in the shape of J. Anderton’s Sleuth, of the M.Y.S.A., which placed a creditable second, and A. F. Hill’s Aegir, of Y.M.6m.0.A., third place boat, so that their “raid” would surely justify an attack in force next year. Of special interest is Aegir’s position, for, lacking a mate when the contest started, German 444

1958 SEPTEMBER, M.Y.A. observer Karl Burghardt volunteered for the job, and proved a most capable assistant, For the first time an entry came from the Isle of Man club Ramsey, and though E. Andrew’s Rivington Lass took up a place at the end, this we are assured will not dampen the club’s enthusiasm for further participation. Ulster as usual contributed an entrant with L. Paton’s Blue Nymph, placed eighth. Sailing conditions were almost ideal throughout the contest, giving steady winds up and down the lake on the first three days, and angled across it on the final day. This gave boats every chance to find their true form, and the result can be accepted as a genuine picture of relative merit. One or two regular figures were regrettably absent, and the fact that the Fleetwood club are not 10-rater specialists meant that three “home” entries A nice action shot of J. M. Fitzgerald’s yacht Alma III coming hard into the lakeside with spinnaker set. were not available, so that some thought might be given to locating regattas on waters where the class is normally raced. As always, the ladies contributed largely to the success of the meeting by great efforts in the culinary line, the larger clubhouse proved a welcome haven, and the news of H.R.H. The Duke of Edinburgh’s patronage of the M.Y.A. came just before the meeting opened. In addition, the B.B.C. put in an appearance, and put model yachting on the air almost imme- diately. At the prize-giving the M.Y.A. President welcomed visitors, and in particular Karl Burghardt of the German M.Y.A. Karl then presented the awards, and in a charming speech in English presented one of his club’s burgees, with the hope that his countrymen could shortly be competing in international events. No. Name | Owner Ulster boat Blue Nymph contests a board with winner Sirocco. | Club | Mon. | Tues. | Wed. | Thurs. | PLACE 1438 | Sirocco aa J. Lace … Birkenhead a | 4 | ot | 129 ie 1381 ale …| J. Anderton M.Y.S.A. ee [ab] Te | ne bss fe Sleuth … 1428 | Aegir | A. F. Hill Vii 6OA. 2; | 38 | «680 | «114 | 44 | 3 1397 | Cordelia ar | P. Mustill North Liverpool… | 38 | 73 | 108 | 38 | 4 | -.| J.-S. Thomas | 86 | 6 979 1288 Estrellita | Alma Il zy | ..| H. Atkinson J. M. Fitzgerald 2 Bristol ee Bolton 29 | eS 51 we | 106 ae 1338 | Francis 1407 | Blue Nymph… L. Paton Ulster – | W [‘-48 | m4 | 1205 94 | | Flora E. J. Blackshaw Birkenhead | 25 | | (59 | 89 le-296 … Bradford ee Eh Soe 38 ke ee ae 1412 | Minerva A. Johnston North Liverpool … | 26 | 57 | 61 | 82 | 1457 | Friar Tuck J.T. G. A. Bissett Saltcoats… evi| 1H l@ | 33 | 9 1055 | | 6 Rivington Lass | E. Andrew Ramsey … | 19 | 40 | 49 | 445 : | 9 8 10 12

MODEL MAKER yachts, their action should be watched from a number of points. Watching the course from the starting and finishing ends, we can see which yacht is making most leeway, and which is sailing the straightest and shortest course. By following the progress of the yachts along lee and weather shores, the closest possible watch can be made over the reactions of the yacht to wind variations. On no account should the STARTING ON THE RIGHT TACK PART FOUR — TUNING BY D. A. UP (Concluded) MACDONALD WE have now carried our tuning-up operations _ to the point when the yacht can be said to sail efficiently on all courses. If the craft is intended for racing, we can now begin to assess its standard of performance by direct comparison. By comparative tests, we can perfect our tuning-up by giving attention to those final details which make all the difference between a first-class and a second-rate standard of performance. For these comparative tests we need a “trial horse”. If our yacht has been built to a published design, the ideal “trial horse” will be a yacht of known good performance built to the same lines. Alternatively, a yacht of similar characteristics, i.e. approximately similar hull form, displacement and sailplan, will serve the purpose. In any case, the trial horse should preferably have nothing freakish about it—exceptionally good or bad performance under certain conditions could make comparative trials meaningless, and peculiarities in the behaviour of the “trial horse” could prove very misleading. Needless to state, the skipper of the selected craft should also be co-operative to the extent of being ready to take part in the trials. It is probable that trial runs with a number of craft will be necessary, since no one craft may be available over an extended period of test. It is not possible to lay down any specific programme for these comparative tests, since the requirements may vary ‘considerably. Obviously most attention will have to be given to points of sailing on which the new yacht appears, by comparison, to be below standard. In general, however, the trials should consist of sailing a number of boards on various courses in relation to the wind, the relative performance of the yachts being carefully studied on each board, and changes of trim tried out with a view to improving the performance a little at a time as the trials proceed. Good sailing conditions are essential for these tests, and it is better to protract them over a period and avoid the possibility of being misled by uncertain winds, rather than to try cramming as much tuning-up as possible into a short period, regardless of conditions. The windward performance of the yacht should receive first consideration. After one or two boards it will be obvious whether the new boat is superior or inferior to the “trial horse”. If it does prove superior, this should not allow us to be complacent—every effort should be made to increase the margin of superiority as far as possible. In studying the relative behaviour of the two s @ Pp t f i i ‘ ‘ Q tuning-up boards be allowed to become competitive —far too much time is lost by tuning-up sailing developing into racing, with more regard paid to making the line first than to the study of the behaviour of the boats. Fig. I shows some of the effects which may be observed. In diagram A, the yacht X, although appearing to sail faster than Y, is none the less beaten at the first turn, although started in the weather berth. Viewed from astern it would have been clearly seen that the yacht was following a “wavy” course, luffing on each puff of wind, and afterwards paying off. The course travelled is thus longer than the straight course of Y, and although greater speed was being developed, this was offset by the greater distance travelled. This sort of course would result from a vane gear set to too wide an angle, and/or sheets trimmed too close. In diagram B, we have a reverse condition—again sail trim and steering gear setting are in disharmony. The rudder is attempting to steer this boat too high in the wind. When this happens the boat loses speed, the sails spill wind, the yacht falters, and pays off again to the course for which the sails are set. In diagram C, we have the same effect in a much reduced form. This sort of course is a very common occurrence, the turn into the wind being very slow, so that at first the yacht X appears to be genuinely sailing fast and straight, and higher in the wind than Y. Were the windward leg a shorter one, i.e., On a narrow sailing water, X would probably beat Y with this trim. This can be seen from the diagram which shows an imaginary shore line at PQ. A turn at this point would give X a very good lead. Small differences in trim between the yachts can therefore affect performance materially and the maximum care and observation should be used, to assess correctly the meaning of results obtained during these tuning-up boards. In Fig Ila, we have yacht X making distinct leeway. This leeway is accompanied by a lack of forward speed. There are two main causes for this effect: either the yacht is overpowered (and this will be apparent from the angle of heel), or the sails are trimmed incorrectly—i.e. sheets too close and/or kicking strap too tight. A comparison can be made between the sail trim of the two craft to establish the cause In Fig. IIb, we have a case of : of this trouble. two yachts reacting in different ways to an increase of wind pressure. Yacht X sails smoothly through the squall, luffing just slightly into the wind. Yacht Y turns into the wind more sharply, until the sails spill, and she loses way and pays off. This may be due to the same causes as those producing the results shown in Fig. Ib (excess helm and tight sheets), but is more likely to be due to the mast position being incorrect. This could well be the case if the d an earlier yacht was one of those mentionein chapter, requiring change of mast position for vary- ing wind strengths.. The technique to be applied here is to arrange matters so that an increase of wind pressure produces an increase of weather helm, or a freeing of the main sheet, or both. The former 456

tension line used to remove the excess helm in light winds. The latter is achieved by a time-honoured process of including a small spring or stout rubber in the main sheet, which will stretch and free the sheet in a strong puff of wind. This latter gadget, although scorned by most skippers of to-day, is none the less a valuable tool in cases where there is serious unbalance in the boat. WIND INCREASESrl og tie fe to reveal any remaining defects in the equipment of the yacht; (2) to carry the preliminary tuning up operations to a more final stage, and bring the yacht up near to its ultimate standard of performance; (3) to familiarise the skipper with the effects of small changes in trim, and establish the best trim for windward sailing under various conditions. Very little tuning-up is normally required for downwind sailing. Speed is determined by the characteristics of the yacht and the efficiency of the sails rather than by minute variations of trim. A straight course is dependent on the efficiency of the steering gear, and the main purpose to be served by sailing parts of the self-tacking gear are heavy, the “toggle” action of the self-tacker will be lost. This means the gear will not fully open until a great angle of heel is reached, and will not remain fully open, when the yacht comes upright. A light tension spring between the forward edge of the vane feather and a point on the weight arm is often necessary to ensure a reliable toggle action. To check whether this is the fault, the yacht should be sailed with a fixed vane at the appropriate angle for the course. A check should also be made to ensure that the vane gear, as trimmed for the course, is “flotation-balanced”. If the vane gear is above suspicion, and the behaviour is the same on both tacks, the cause is a design fault or an inaccuracy in hull construction. A “gimmick” to reduce this trouble is a spring in the jib sheet, which gives a luffing tendency to counteract the tendency to bolt. I know of two yachts which bolt quite violently in strong winds but have been tamed by their expert skippers to the extent that they perform very successfully in open racing. down-wind against a “trial horse” will be to check that the operations on the vane gear carried out previously were done correctly. The opportunity of down-wind sailing should however be used to the best advantage to practise the setting of spinnakers (both balloon and flat). The effect of the mainsail kicking strap on down-wind sailing should also be studied. On some yachts it is necessary to slacken the kicking strap appreciably for running before the wind, either to increase the drive in light airs, or in the drawings of Figs. I and II. No doubt our “trial horse’ will itself fall short of perfection to some extent, but if it is a good yacht of the same type as our own, we shall have quite a bit to learn to excel its performance. The tuning up experience will serve three main purposes :— any WIND LA il | WIND LIGHT | WIND FRESH WIND |ae We ghee e, to prevent broaching in squalls. Comparison trials with an opponent of known merit will naturally help towards determining the best method of dealing with these problems. It is worth carrying out careful practice in the setting of spinnakers for quartering winds. The general principle is to set a balloon with an appreciable topping lift, and the boom Finally in Fig. Ile, we have the yacht which falls himself to a situation where the mast position will have to be varied for best results under each set of sailing conditions. In mild cases, however, a change of vane angle is all that will be necessary to provide sufficient correction. It will now be obvious from the foregoing that we are, in effect, attempting to tune the new yacht up to the standard of performance indicated by our exemplary yacht : (1) In Fig. IIc we have a case of “bolting” in a strong wind. This behaviour is usually accomplished by the reverse action (shown in Fig. IId) when the wind lightens. A simple cause of this fault may be in the vane self-tacking gear. If the vane feather and its counterbalance are light in weight, but the inner away in a light wind. This is the most common form of misbehaviour, and, in fact, a_ perfectly balanced yacht will do this to some extent. (Even our exemplary “trial horse” X is sagging slightly in the diagram). This effect is probably associated with the tendency to luff excessively in a squall, as shown in Fig. IIb, and the treatment of one fault may well cure both. If no results are achieved by simple means already indicated, the skipper must resign gt squared off, when the wind is astern. On a quartering wind, the topping lift is discarded, and the boom held well forward and hard down. The correct technique for varying directions and strengths of wind can only be worked out by continued practice. The technique for maximum performance on reaching winds will vary considerably according to the characteristics of the particular yacht, and, again, a continued cut-and-try methods of tuning up neécessary to establish the best technique. In general, it may be said that yachts with low aspect ratio sailplans (i.c.. 3:1 or less) respond best to trims which give the sails a pronounced conical form, as described in an earlier chapter. This entails a fairly slack kicking strap, allowing possibly twice or three times as much lift of the main boom as for windward sailing, and sheets trimmed for boom angles between 25 and 35 degrees. This type of trim is associated with heeling angles of up to 25-30 degrees, i.e., it is applicable to yachts with an “easy” type of section‘ Yachts with high aspect ratio sailplans (over 3:1) and/or a highly stable section, are best sailed upright with the sails set in a form conforming more closely to airfoil technique, i.e., well cambered with a kicking strap set only slightly slacker than the ontimum for windward sailing. The boom angle for an exact reach will be up to 40 or even 45 degrees. Yachts to recent “Duck” designs respond particularly well to this treatment, and their hull (Continued on page 474) 457 | can be achieved by additional helm obtained by setting the vane gear to a wider angle, with the 1956 ot SEPTEMBER,

MOCEL AEC) A Ship for Onen Water Sailing An eleven-footer for sculling or rowing, designed for model yacht sailing but equally suitable for fishing, pleasure use, etc. Complete plans are available, price 15/- per set. By H. B. TUCKER PART TWO The chines are prepared by planing off the lower Now in this _ outer corner according to plans. connection it should be observed that actually this bevelling off will only be correct as far forward as Section 2, because ahead of this point the rise of] that | une a ete the floor becomes rather steeper. Hence the builder) -— —— must be prepared to find further bevelling necessary| ‘“* ° at the forward end. The same applies to the keelson. _ When fitting the chines, it is necessary to bevel both sides of the notches into which they fit to make the chines take properly right across the floors and frames. The forward ends of the chines have to be chamfered off to fit against the stem and stem knee, MARKING OUT FLOORS FOR CUTTING 2 re i 7iLIMBER c oe HOLE FOOT OF STEM HORN CUTTO STANDON FLOOR BEARDING ee also on the underside where the chines run into the keelson. In the course of fitting these, the keelson can be shaped in plan, but leave the adjustment of the angle of the bottom of the chine and the bevel of the keelson rabbet until you are ready to fit the skin. When fitting the chines in place, do not forget that their forward tips fall at the bearding line as FRAME — kn etell explained for the thwart stringers. fore, as soon as they are cut, they should be given a coat of paint, and further coats applied from time Ea to time as work proceeds on other parts of the boat. Thus by the time the boat is ready to receive her skin, the limber holes will have received four or five coats of paint. White lead paint should be used | – it will be glued to the skin, or the glue joints will be can be put in place gunwalé corners to be bevelled off later when thetwine, anc is dealt with. Take some strong string or put bindings round the frame above and below the you start bending these. These notches before ion to obviate bindings are temporary and a precaut the process amy chance of the frames splitting during glue will of bending the inwales into position.rd The brass single a forwa but place, in s imwale the olid n positio in firmly them keep to ld used be ou sh _ gerew 3g [/ g jo 7 Sa ‘ | ee j i | tl stem and breasthook. Likewise a screw it = = em / i we s are the inwales. They frame member as they are, leaving the inner t The d.final – impaire Livers a1 careful not or a mixture of red and white lead. Beframe where |,’ t+ Sts See to get the paint onto the bottom of the — When we are dealing, with the frames, I mentioned the limber holes. Once the skin is on, it is impossible | gorzom of o7 .. to paint these properly to protect the wood. There-| se 2553/4″ — 23″ —

‘ — FULL SIZE SECTION LW.L. CL. FORE & AFTER :— GAUGE aio STEM WIDTH ON LW.L. oe TMs €& BEARDING LINE ON EACH SIDE AS GUIDE TO CHAMFER. . TE STEM BEARDING LINE GAUGE GL. TOP & 80) Born LINES ON SIDES ara AS GUIDE TO ar geneaiCtee as! vara=fdj ® ® — FORWARD SIDE i994 +| | ‘ae o%d | ‘ BEVELLING CORNERS. Sie 138 ee meee | 22 }¢-—_—_—_—- fd yi ie i Yous fe & s

mpoel to let her pass. The delivery deals with water already in motion, and trying to flow back into the hole astern left by the vessel’s passage. Thus the entry pushes the water outwards, while the delivery regulates its flow inwards. Hence it can be seen why the entry must be shorter and blunter than the delivery, and the delivery as long and easy as possible to reduce disturbance astern to a minimum. It may be added that tank tests have amply confirmed these facts. However, the shortening of the forebody of a displacement type yacht cannot be carried to the same extremes as in light, manned-up craft, where the movements of the crew affect the position of the C.G. – In a displacement type, such as a model yacht, if the entry is too short and steep, when running the vessel will pile up water ahead of her, and ride her own bow wave. At the best, she wiH do a sort of bogus planing, making immense fuss and little real speed; at the worst she will plane a few yards and then “blow up”, broaching violently. Such a boat close-hauled will have her balance upset in the same way as if her C.B. had moved forward sharply, and perform similarly. On the other hand, if the delivery is too short and sudden in relation to the entry, water will pile up under the stern, causing a similar effect to that produced by a movement aft of the C.B. on heeling. In designing a fin keel, the profile is the first consideration. Too steep a leading edge upsets the yacht’s dynamic balance by making her too ardent. In this connection, we have also to consider the position of the toe of the fin, because of the necessity of placing the C.G. of the lead ballast keel far enough forward to counterbalance the vane steering gear. Hence there is a temptation to make the leading edge of the fin too steep in order to cut down wetted surface, and shorten the overall length of the fin. Inexperienced designers often think that because a racing dinghy or “Flying 15” can get away with a dagger fin or seal flipper, a model yacht can do the same thing. Lateral resistance provided by any given area depends solely on speed through the water. Since the density of the water is the same for models as full-sized craft, it is not a question of scale area of the lateral surface but of the actual area required by the craft herself, and scale speed does not enter into it, but actual speed. In consequence, the model requires more lateral plane proportionately than a bigger craft. There is nothing to guide the designer in this respect except either long experience or study of the works of others. It is essential to have sufficient lateral area to guard against undue leeway, while avoiding unnecessary wetted surface area. In this connection, we have to remember that resistance due to wetted surface e is most important at the slow speeds resistanc engendered by light airs, but at the same time, the tendency to make leeway is greatest when the boat has bare steerage way, or at the other wind extreme, when pressed too hard and “sailing on her ear”. Hence slightly too much lateral area is a better fault than far too little. Having decided the profile for our fin, the fin W.L.’s have to be settled. As is well known, too coarse a leading edge or too abrupt an entry to which will the fin will set up a heavy pressure area, eep leading have much the same effect as an over-st aded. edge, and make the boat ardent and hard-he entry Per contra, the same conditions apply as to the and delivery of the body in their relation and pro- portions. But since the fin is always totally submerged, we can advantageously, make the entry of the fin just a shade shorter and blunter in relation to the delivery than we did with the body of the boat. Here again, experience is the only guide. I may add that most experienced designers have rough and ready rule-of-thumb methods to place these points. Finally we come to the streamlining of the garboard angle. This is even more important than that of the fin, and I may add, more difficult, since at all costs we must avoid water-choke in the after end of the lee garboard. One way of avoiding trouble is to use a totally unfilled garboard, when provided the hull is correctly balanced between entry and delivery, and the fin likewise, all choke should be avoided. This has a further advantage in that this angle between fin and hull seems to increase lateral resistance. On the other hand, the unfilled garboard is not pretty, and a chance is lost to stow away a little displacement, where it will do no harm. Likewise, it entails a slight increase of wetted surface area. Of course, the unfilled garboard is correct technique in a sharpie, which is why a sharpie to the M-Class rule is an abomination to the purist at all events. As water travels along the garboard angle, there is a steady build-up of pressure, because we not only have the ordinary waterstream caused by the water flowing round the yacht as she moves forward, but lateral pressure due to the leeway the boat makes. As a result, the water pressure reaches its peak towards the after end of the lee garboard. Hence it is essential to design the garboard to accommodate this, and give room for it to escape gently, but sufficiently swiftly. If the after garboard is too short and coarse in relation to the forward garboard, the pressure of the trapped water can be sufficient to raise the stern, and thereby cause the boat to gripe badly. In the garboard, the entry is relatively shorter in proportion to the delivery than in the fin, so as to make the delivery as long and gradual as possible. “Boiling at the skeg” is a sign that the after garboard is too short and not easy enough. Static balance is entirely a matter of hull design. Dynamic balance is mainly a matter of hull form, but sails have a certain amount of influence on this also. Yet this influence is far less than most model yachtsmen think. On the other hand, the influence of sails on performances must not be under-rated. Perhaps the main respect in which sails influence hull balance is the down-thrust which they exert. The force of the wind on the sails can be mathematically resolved into three separate forces. Of these, the greatest is the lateral pressure exerted. This represents about 60 per cent. of the total force. and heels the boat and presses her to leeward. The second largest component force is the down-thrust which represents perhaps 30 per cent., and this downthrust definitely increases the boat’s displacement and causes her to settle in the water, thereby increasing her sailing length. The third component, which only represents about 10 per cent. of the wind’s total force. pushes the boat forward. The above applies, of course, to a boat sailing close-hauled. As the wind draws aft, the lateral pressure decreases and with it the leeway made. The down-thrust also decreases, and as these decrease, the prope#ant component increases. What we have to consider in connection with balance, however, is the effect of the down-thrust on the close-hauled yacht. Naturally, this down-thrust 480 varies continually

SEPTEMBER, according to the strength of the wind. It might be thought that this would manifest itself in the form of a direct down-thrust on the mast, and if this was so, the only way to avoid a constantly varying foreand-aft trimming effect would be to step the mast exactly at the fore-and-aft position of the C.B. It does not seem to work this way fortunately, and practical experience has shown that it makes little or no difference in this respect where, within reasonable limits, the mast is stepped. With an unbalanced yacht, the position of the sail plan over the hull is very critical, and in this respect, the ratio of head to after sail must be considered, also the aspect ratio of the sail plan. On the other hand, the better a craft is balanced, the less critical is the position of the sail plan over the hull within reasonable limits. The tendency is 1956 the entry must be shorter than the delivery, but other than experience there is nothing to guide us as to their relative proportions. Hence, anything I could put forward would be a personal opinion. I have been designing and studying design for over thirtyfive years, and during that time I have executed some hundreds of designs. The more I study yacht design, the more I realise how much there is to learn. Life is too short to repeat grandfather’s mistakes, so all we can do is to study the designs of successful boats for what to emulate, and unsuccessful boats for what to avoid. Hence, although I have certain opinions, I have refrained from airing them here and confined myself to incontestable facts, but I have tried to marshall these in a way that will assist readers to form their own opinions on sound lines. ~ In fact, there is only one conclusion that can to overstress these points, especially when one remembers that some well-balanced yachts will tack to windward under headsails only, while others handle nicely under mainsails alone. In my last sentence, I am speaking of experience with full-size yachts, but it helps one to realise the great importance of perfect hull balance. On the other hand sail design has a great effect on performance, though sail cut, bending and trim safely be drawn after an examination of the problems of static and dynamic balance. In order to design a successful model yacht, static balance must be perfect, and every feature that can introduce a steering effect must be sedulously eliminated in order to achieve dynamic balance. After that, speed must be sought by perfection of hull form and the elimination of features liable to slow the yacht and cause water disturbance. Finally, our type and however, is that it is no use expecting the sails to counter the ill effects of a badly balanced hull. Some model yachtsmen (and designers) are misled by the fact that on occasion unbalanced boats have rule governing the class for which our yacht is intended, always bearing in mind the weather conditions likely to be encountered. ; Of these various considerations, static balance can perfectly true that some unbalanced boats are extremely fast when conditions just suit them. The balance is only certain when any feature likely to cause dynamic unbalance has been carefully are put even up more important. remarkably good The point performances. to stress, It dimensions must be selected to get the best out of the is be definitely assured by calculation, but dynamic explanation is, of course, that at a certain angle to the wind, and in a certain weight of wind, the boat’s’ eliminated. Perfection of hull form is largely a matter of the designer’s skill and artistry. When, vices more or less balance each other. Nevertheless, these yachts are usually extremely difficult to sail, however, we come to the question of the sélection of type and dimensions, it is purely a matter of opinion, though experience and the ability to sum up a rating rule are a guide. Yet if our boat is and even when everything is in their favour, call for most expert handling, and at other times are just “pain in the neck”. a being designed with any specific race or series of In this article, I have treated the subject of dynamic balance on broad lines. races in view, weather conditions can always upset our For examples, we know that most careful planning. syemuny a 42143 ,F Btde Sebe “RO ?(u973eg BuyeYyd 40) axe435 Zuiqqny “* — BAOGE Sly :S}B9Y4SU493S pues SJUEMYL POOM JRIIWIS JO [eaq ‘auUlg MO]ja) :Sspavoqsoojy i 42143 wt ee ee ee wee ee wee aaoge HPO JO Bulg YJ :sjaey S3jI1g POOMA]g pepuog ulsey sO PY? 7 4142 ,F POOoMAld papuog ulsey 40 i: ai swuoseLy UNS DAOE S\¥¥ :S4BZUIAZS JABMYL on BAOQE SY :SO]eMU] “ae = ““BAOGE SY :S4BZUI43ZS BUIYD “** gaoge Sy :(S8lL a[Zuy sUIYD) s3essny5 42142 ,£ By AOE SY :9} BI Pelu4szUj—s40o0j4 42142 | al “es x ,¥| tee ee wee DAOge SV :UlePJ—s400/4 wee wee nee saoge sy tsoulesy POOM JBIIWIS 40 [kB ‘BUlg MO}[a\ :SedBIg UOIYsey ° + JPIUOZIIOY Ule4IZ YIM SAOgE Sy :wosue4sL apis IseZuo] O2 jajjesed ules yIIM AOE Sy :eeUy LUaIS #Zx LI vee Bad POOM JPjIWIS JO [eaQq ‘Ulg MO]ja) :(4aquiay 4auU/) Was AE wth Py te, m x POOM JBIIWIS JO [kaq ‘aUlg MO][e, :WOOYIsSve4g = 4eO 2 (4aquiay 493NC) /4¢ ee ee oer wee see COM ARIUS JO jeaq ‘AUIg MO][ea, :(UOSJaay 40) Brd0IdZOPY SONIILNVODS JO 318VL ddINIS ONILHOVA 15300OW oA SUIpieyol JO pvojsur 29q 0} sjres ssoisoid ImoA suaddey 94} Jey] OS PpUIM pre 94} UOTYse] [jim Aay} usyM ssojUN ‘puIM syI[URUIeES B 0} UT osed Ul Uloyse peoy }eOq ae 94} ‘polisap JI parinbol st AouevAong UI eijx9 Jy “osm OJ 2OUyY-Ws}s 94} DAOQge ysl Wod}s 9Y} JO ops Joje oq O}UT jnd 3q JSNUI }[OQSULI posiuvales Y ‘pojuted aq 0} Apeol st Ylys 94} ‘dn pouvays si SuryjAIoAo sy AA ‘Ua}S ISUUT 94} JO opis Jaye 24} Woij ul nd 9q pjnoys smoios ayy PoMolos pUe PoN|s SI “uOoTsod ur Ula}]s I9jNO 94} ‘Apeol USN AM “UNUNUIW & O} SUIAIVD JO JuNOWe 24] sonpel [IM sIY] “peoyurays [enjoe oy] ULIOJ wed do} 34} 0} ponjs oq ued yoru) “‘urt IO) saosid OM} YOIYM Jo\Jy ‘“UWa}s [enjoe 0} (syeays 3y} jo IpIM oy} 0} UMOp peur] st WO}}0g 0} do} wWoly W935 sJOYM oY} Jl Moqe[ pue UIT] SARS “IZAQMOY ‘[]IM I] ‘o8no0s & YIM YO J9UIOD 94} Sutrareo Aq Apjeou ainb epeul oq Jo}VUl & ued SI SOUdIIIP “** BO JO aulg ‘yoII1g (4aquiay 422NQ) BAOGE SY :(4aqUia-; J2UU]) pazeUulLUE] ‘Ja05y i ; % XAT at X,4 SIOYojoljs Apvol MOU SI YIyS INQ “Ul[UIo}]s B IOJ s}ooYsUIays 24} eAoqge jsnf WoOsueI] 94} JO spIsoOJ oy} O}UT ynd SI YOQsuULI Ia[[eWis ynq ‘IepiuNs Y “JoyUIed 3y} I0jJ sy 2305S asenbs || 42142 ,F suenbs |= ok X Fl auenbs | are al OJ a[qelins JO swmMIptio Jo sfdnoo ev ‘suidwems Jo jasdn jO ‘APPAIUIAIY “a2QYNS [JIM 3 asimsayIO “pesn aq ued poomdid 7 ‘y2eeq Auojs Au9A & UO pasn aq 02 SI 380g 32 jj —”aI0R—N yPYy3 ,F 34} “}IBMY] O1]U90 94] Jopun Poyse] oq Ud oZIS JEWS IO “OOE BITOJOY WIM opeul eq 0} syutol TTY 42142 + “AysuIp SUIMOL [[PWS B Ul [OPO sIy YIM URWs}yORA [OpowW ev jo ydeisojoyd e ‘oulzeseul & ul Mes [ ‘AT]UID0Y “Ajisea ajinb pony. “sS¥IQ 9q O} POSN SMIIOS [[YV Mea Ge | jUJa\se AYSUIP oy} Seip 0} BuIA 2J3M sjles sjyoeA JOpOu oy} BIYM ‘peoye AjsNO1OsIA Suyjnd sem Jeddrys o4y, ‘esimod s,AysuIp oy} Weog wnuwixeyy “Ul6 “WE sAoqe Jepow MOA MOG sdiysprarny yidoq ‘Ug “WI UWis}S UOTOUN 34] pue pis Was puke PedYyUe]s 94} WJ, 24], “9ZIS “SYjpIM 3991109 poeysiuy 34} yore U2eM}9q 0} ‘ult jo YIPIM UI uo] SI p2onpal 2aqdedsel 1194} IOJ yorq pue juolj UMOP soul] jnd Udy} ‘WIa}s ay] JO yorq pue yUOIJ UMOP “YySUIT ye “Ul Z OJUT sUTJaI]U20 OY} JO SI Opis DL} O} -W9]S 84} Je 24} Oy [enbe e s5ned 3821 3Y} JO} PIeMIOJ ayes pue si 34} UO Sulgqni “UTyYs aoevy snjd Jajje 0} “Ul, days oY, Osje Wa}s st JouUT JO jsIy UT peeyWajs oy} YIPIM oy} sy} SI pue ‘yUNODOR sayy oy} YIPIM JO 94} pray YIpIM s0U0Hy (ond mosfponus4eD) ONITIWS YALWM NidO YO 44IMS iis —— ‘qyerooidde osy[e [IM ouIzeseur jUaTjeoxe jsOUE INOA JO SJopeor OY} Jey} podoy st yt YOM ‘JUSMESNWIe PUP JSOIOJUI 194} poaoid sary Ady} a1ep 0} dn 4nq ‘sfomuos pue dnyoid Surse9qs oY} 0} SUONROyIpom AuruUl udeq BAP BOUL, *‘poysedxe oq prnoys Se UOTOUNy 0} sado1d pue s}iq Jopouwl Sumj}03 Jo Ay[NOWIp 24} 0} ‘Jqnop ou ‘anp syyUOW se7U} Ajeyeuntxoidde useq sey Jef} OS udye} OUT ‘Surg? jenjoe “nod 0} UO passed oq [IM Uoneuroyur oy} yey pedoy st jr ‘suoye oy} SUIOD SJUSTUSAOICUIT Ssoy} SB ‘pue ‘ape oq ]TIM SISI[BVSI SJUSMSAOIdU 1QnNOp ou ‘sesseIs01d ou sY Soop ptyo & Aq poyeiodo uoyM YSnoyye ‘sour BA 0 0 Aes € 1 Our 10 CG pe Goo – 8f¢€ p’s F jo yous Vy “ry 0 0 “* sjieu jo joyord sup “ [| QO “ suorutd jo med euQ € a aoe Ok ero ILO * : 0 useq 3}IXNT4 suIOs pue Jepjos FiO. – Ce) 0 61 8. 1 F el #9 @ SIOJOU OM], FO… sytney Setpung Inoz sexoqg Jomuos omy —:0} sjunoule jsoo JNOAL] [B}0} OY} ‘puey oO} preoqpsey oy} SuAry ‘MOT ATPUIOIXD Ud0q Sey eP 0} 1S00 oY] 9$61 [elognie SuryjoWos jo ino OY] pue YIM peonpoid ul ‘pue pue sey squiyo i[NoWIp 00} ‘siolIeg pue sui) daoid JOU -ulmopeid ul useq sey yom jd pue ‘suMIOxe Ayenbo ‘olojoioy} ‘puke pores Ajouemxa SOE ft Iveu ‘YWAEWILdIS sey souvulojiod oy} sep 0} dq DUBULIOJIVg [B19 “uns Jeojouyyiie sjduis AIsA WY “spuooes ¢/Z’¢ Jo oul} & UT 1Z/Z JO JMOMD & IJDAO ‘Y’d’wW OO] Jo poods ofeos e ‘AjoyeuTxoidde ‘ureyye 0} ‘pojeis useq Apeolye sey se ‘pue uororjsnes o[qeuoseel 0} dn yInq useq sey yNokeT oy YOIYM WIM poeds oy} poroyjing [je sey siyy ‘“sdoys om JO SUINIY eSO[D AJOA & payeyIssooou you Aqorey) pue dnyord yjoours A19A eB DATS sey syutol om) ye Aressooou SOYA J0YI080} aseq] Sufropros