- Radio-Controlled Sailing Method

- Vane Control: Automatically adjusts rudder and sails to wind changes

- Full Radio Control: Allows manual control of rudder and sails from shore

- Equipment considerations:

- Vane control needs only rudder control (simpler, lighter).

- Full control requires progressive sheet adjustment and more complex gear (e.g., four-reed radio or carrier-wave receiver with relays).

- Yacht Design and Balance

- Balance is critical for performance:

- Mechanical Balance: Hull should maintain direction at all angles of heel.

- Avoid designs that cause curved sailing or instability.

- Reduce buoyancy in topsides and maximize out-wedge sections.

- Ensure proper equilibrium between sail pressure and keel weight.

- Large load waterline area improves stability.

- Championships and Volumetric Balance

- Entry limits removed—clubs can enter unlimited boats.

- Emphasis on administrative effort behind organizing events.

- Debate on hull balance:

- Volumetric balance is essential but not always sufficient.

- M/C Shelf system (Admiral Turner’s theory) ensures practical balance, though not universally accepted

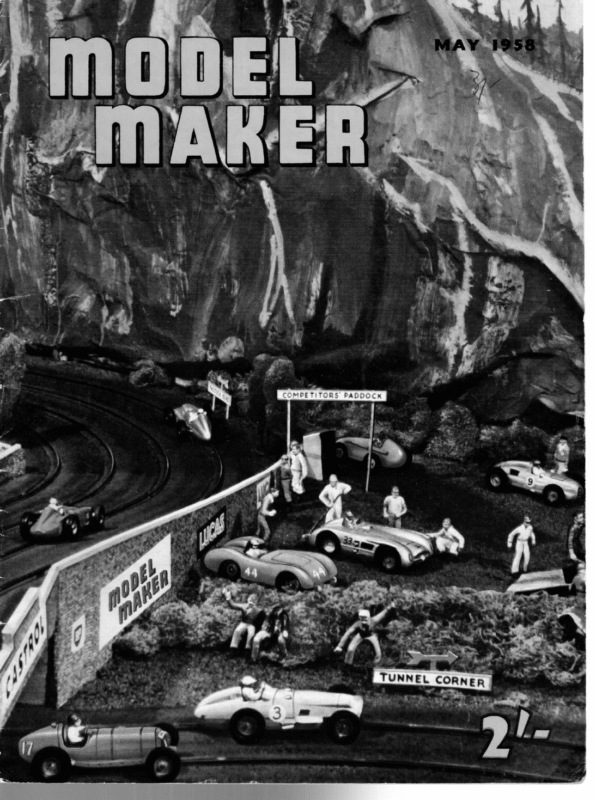

TWO TRIED OF AND CONTROL PROVEN GEAR SYSTEMS USING FOUR- REED RADIO, IDEAL FOR FITTING TO ‘CHINA BOY’. RADIO CONTROL FOR UCH has been said about the methods of sailing under radio control from time to time, so it is necessary in the first place to weigh up the pros and cons of the two methods before deciding on the type of equipment to build into the boat. This is quite apart from considerations of the type of radio equipment which one desires to use and which again has a bearing on the method used. There appear to be two schools of thought on the matter and each must necessitate a different method. On the one hand there are those who say that the boat should be sailed by the vane (that is to say the vane automatically trims the rudder or sails to compensate for any variation of wind direction on a given course), and those who prefer to have the rudder and sail trim under their own control from the shore. The former method, or variations of it, are ideal theoretically since the vane must react to wind variation instantly whereas the helmsman on the bank must wait to see what variations are necessary and then make them. The first method therefore is likely to give more efficient. sailing and is possibly to be preferred for out and out racing. On the other hand the second method gives one the feeling of being the skipper of the boat, having the control of the tiller and the sheets in one’s own hands entirely, and is therefore in the writer’s opinion BY JACK GASCOIGNE MARBLEHEADS a very much more interesting way of sailing. Before making the final decision on the method of operating, it is necessary to consider the type of radio and auxiliary equipment one wishes to use, bearing in mind space and weight factors. The vane method requires rudder control only and can therefore be operated by pulsed carrier-wave radio of the simplest type. With the other system one also needs sheet control in a “progressive” form, that is to say one must be able to trim the sails either “in” or “out” to any extent. This sheet control, as explained later, can operate the jib and mainsail coupled together, and is generally used this way to obviate any further complications. Therefore either one must use four reed radio equipment, or a carrier-wave receiver with the necessary ancillary equipment in the way of relays, delaying condensers, etc., to give the four separate operations required. Referring back to the vane method it should be pointed out that this can be operated by a reed receiver equally well, using only two reeds. It must be realised that an “M” class yacht is rather restricted in space for housing the equipment and also in the weight of equipment it can carry and still sail reasonably well. Again, all extra weight carried in the equipment means that the keel weight must be reduced accordingly if the boat is to float on its designed water line. Therefore the whole “works” should be as simple and light as possible to retain reasonable sailing qualities. A further point to be remembered is that the equipment installed must be kept free from water (particularly if it is salt water). This means not only bilge water but the water that breaks over the deck in choppy weather. The writer therefore recommends that the whole of the operating equipment is built into a box rather than being built directly into the hull. This arrangement also allows for taking the Box lid removed to show automatic sheeting set-up as in heading picture. A, Steering Unit. B, Sheet haul mechanism. C, Motor for mechanism. D, Radio receiver. E, Batteries under receiver. F, On-Off switch for radio protrudes through lid. G, Swivelling contacts 232

MAY, 1958 Box removed from the model; this time controlled sheeting is fitted and the required limit switches can be seen in position. As ppemeReaes fore nag h of equipment is only Oz equipment out of the boat as one unit and for easy setting up and testing on the bench. Again for transport the box can be carried upright, leaving the hull and mast, etc., to be carried as convenient. Referring back to the vane method, it should be mentioned that below a certain wind force there will be insufficient effort from the vane to operate the motor contacts effectively. This can be offset to some extent by fitting a larger feather in very light winds, but it would be necessary to balance out the whole unit carefully for these conditions. It is assumed that the reader has some knowledge of model yachts, so therefore the principles of sailing will not be entered into here. The yacht should first be tried out for free sailing, and any adjustments necessary for normal free sailing made. A note should be taken of the angles of the booms when close hauled, reaching and running, so that the sheeting arrangements can be designed to suit their angles. Two systems of sheeting are shown in the. sketches, both with the two booms coupled together. With these arrangements the main sheet has double the length of haul of the jib sheet, therefore to maintain the same relative angle on each boom in varying positions the point of attachment would have to be twice as far from the swivel point in the case of the main boom. Now if, when reaching or running, one requires a greater angle on the main boom than the jib boom, the point of attachment on the main boom should be brought nearer the gooseneck. methods of operation have been used. The sheet haul mechanism is made from an old alarm clock. The escapement and the first gear train were taken out and a Mighty Midget motor coupled to the second gear train. The winding ratchet is soldered up solid to its gear and the shaft drilled for the piano wire operating arm. For vane operation, a rotating arm with two pairs of contacts is fitted. the systems as used need modification so that there is some spring loaded take up arrangement between the vane gear and the contact arm, so that the contacts cannot be overloaded accidentally. For independent radio operation of the sheet haul mechanism two limit switches are fitted instead of the rotating arm; one of these is indicated in the sketch. Both the sheet (Continued on page 257) FOR CLOSE HAUL) To enable the two booms to be set at their correct relative angles to each other when close hauled, the usual sliding bowsers normally used in free sailing should be fitted on one or both booms to allow for adjusting the sheet length. The positioning of the aerial requires some consideration. It should not be fixed to the mast if this is made of metal, and it should be kept as far away as possible from any metal rigging wires. A _plastic-covered aerial wire direct from the receiver and attached to cord rigging is a very good arrangement. However, if the mast and rigging lines are both metal it will be necessary to have a rigid self supporting aerial fitted from a base attached to the deck. In this case it is essential that the base is insulated against moisture. The photographs show an installation in an “M” class yacht, and as can be seen both 233 This arm is direct coupled to the eccentric on the vane gear. See sketch. It should be pointed out here, that IXEO CONTACT ARMS, CONTACTS ECCENTRIC, THROW TO SUIT TRAVEL REQUIRED NORMALLY OPEN 2 : S X\. ). FIBRE CONTACT ARM SWIVELS FREELY ON GEAR SHAFT FINAL GEAR OF DRIVING MECHANISM ” NORMALLYSIMILARPies pea LIMIT SWITCH FIXED A SITE END OF SHEET ARM TRAVEL ELEVATION pe SEL ScaLe: 4@ Fy PINTLE FOR VANE GEAR TO TURN ON. (0) S i

A Ye RESTRICTED CLASS MODEL | ~ LIBRA OESIGNEO BY WJ Daniels OF COPYRIGHT NE rw =. WATFORD, i a SERVICE weERTS [ee me a 2 3 Brie toes Ta \ \ \ = oe See ee 7 8 is, | oh SZ 9 [ APPROX. POSITION: FOR MAST = ; Pee ie ge arenas ed LEAD MS ‘ \ LW. se a ESPs a W.L.8 6 eae ee ye 5 as oe SS —— 4 : AN WL \S aN Bed Wis wi4 | y H if = J, | os | \I ere ut W.L3 nes TABLE OF WEIGHTS HULL WL i PLANS we, CLARENDON RO, Alli MODEL MAKER DECK with HATCH Ib. oz. | PAINT & VARNISH RIG- Sails, Spars, ete. FITTINGS LEAD KEEL 7 8 DIMENSIONS LOA Gees – LW.L. 2 : g6.04 vie 12 Mex. BEAM 12 14 Max. DEPTH Mex. DRAUGHT SECTIONS spaced BUTTOCKS spaced 11.0″ WATERLINES spaced 1.0″ 6 8 i112 ! 3.6″ 1.0 ‘ ! ’ : 9.0″ 7.4″ | ! —————— SAL AREA ay carters MAIN SHON IBIS» 507 cae aes ED ee eet

MAY, T is surprising that the designers of full-size BALANCE IN yachts have not taken more interest in the work and research that has taken place for many years among the model yachtsmen of this country. This perhaps is because most of the models are of the fin and skeg type of keel. It must be admitted that this latter type is at a disad- vantage in the full-size as the turning moment is much slower owing to the rudder post being at the after end of the water line, and it is difficult to gibe without freeing the mainsail, which would put a yacht at a disadvantage especially in the starting manoeuvres. It also has been the general belief that the model can be better controlled with this type, but this is not necessarily so. With the pitch of perfection in balance that has now been reached, model yachtsmen will now have to study the waste of time in tacking as the ability to make a quick tack is often the deciding factor in winning a windward heat that takes only a few minutes to sail. There are two kinds of balance in yacht design. There is the balance of conflicting forces and the balance in which the model at any speed or any angle of heel has no tendency to travel other than in the direction of the centre line. The weatherly yacht is not one that is trying to luff into the wind. The old idea of the lee bow wave being the little man with his shoulder pushing her up to windward is entirely the wrong line of thought. The beautiful bow and lovely run disappears directly the yachts heels. Sailing is a mechanical operation, and if the yacht is not mechanically correct she will not put up a consistent performance but will only have a particular angle of heel, and speed conditions at which she gives her best, and this may not be striking. If the design is mechanically perfect the yacht will sail correctly irrespective of conditions of wind and water, and her performance compared with other yachts will only vary in comparison with their relative lengths and sail areas, and perfection of design. It is quite possible in a design for the boat to have a tendency to sail in a curve. This nearly always happens when sailing to windward. It may be the result of wrong trim (by the head) and it may because the hull diagonals spread towards the after end, thus bringing the “line of direction” of the hull at an angle to the centre line; it may be that the rig is too far back in the hull. The difficult thing of these is curing a fault in the design. If the 1958 YACHT DESIGN EXCERPTS FROM A TAPED CONVERSATION IN WHICH BILL DANIELS GIVES HIS VIEWS TOGETHER WITH TO THE | BRA M.Y.A. 36in. A NEW DESIGN RESTRICTED CLASS boat is out of balance it may be checked by extending the deadwood further aft or moving the fin further aft, though this is really introducing another force to cancel out the first, with subsequent effect on performance. It is therefore apparent that the very first essential in a design is that the shape of the underwater hull must provide at all angles of heel a sense of direction parallel to the original fore and aft line. It is further necessary to see that the boat does not rise on her edge as she heels. In a design with normal sections it is not possible to prevent this entirely, but it can be reduced to a minimum by reducing the buoyancy of the topsides and increasing the out-wedge of the section to its maximum, which means, of course, keeping the bilge low. It is not particularly helpful to balance the in and out-wedges as far as possible; what must be depended upon is the righting moment of the boat, or rather the wind pressure on the sails in equilibrium with the lead keel. Only by the depression of the boat so created can the hull properly bring her overhangs into play and so increase her sailing length. A further help in this connection is to get the maximum area of load water line plane consistent with good lines. The contribution to stability provided by beam does not arise simply from the maximum width of the hull, but from the total area of the l.w.l. plane. In this connection one of the worst outrages every perpetrated in the world of sailing was the insistence, in certain classes, that the greatest body cross-section should be placed at 55% of the l.w.l. This must produce an unbalanced hull in that the afterbody lines must be fuller than those of the forebody, and the rate of delivery of the water cannot be matched to the rate of entry. Taking a large craft of 100 ft. w.l., the forebody will be 55 ft. in length and the afterbody 45 ft.—nearly 20% difference. The effect is to produce quantities (Continued on page 247) 253 i]

EE MODEL MAKER) ~ UCKER’S TOPICAL TALKS SS CHAMPIONSHIPS Actually this limitation of the number of AND VOLUMETRIC yachts that a club could enter in a National BALANCE TJ of HREE of the National Championships the 1958 season are being held during May. have now taken up the M-Class, but are not included in the above figures. These are:— The 36 in. Restricted Class at the Long Pond, Clapham Common, on May 3rd and 4th. The 10-Rater at Gautby Road, Birkenhead, on May 24th to 26th. The 6-Metres at Bournville Lane, Birming- ham, on May 3lst and June Ist. In a way it seems rather a pity that the biggest events for three of our five National Classes take place so early in the Racing Season, as afterwards such races as Club Open events, Club and District Championships, etc., are all in the nature of an anti-climax. The other two National Championships fall much later in the season. They are:— The A-Class at Walpole Park, Gosport, on August 3rd to 10th. (N.B. The International Races for the “Y.M.” Cup follows the A-Class Championship on August 11th). The M-Class at the Lagoon, Hove, on September 13th to 14th. All of the M.Y.A. British Open Championships have one new feature in common, since there is now no limit to the number of boats that can enter any of these races from any one club. This limitation of entries from individual clubs largely arose because certain members of the M.Y.A. Council of that date considered there was the danger of competitors, who themselves had no chance of being among the placed boats, deliberately throwing boards to clubmates. _In addition, it was felt that when Championships were held on waters where the home club had a large fleet of the class in question, there was a grave danger of the entry being swamped by yachts of the home fleet. The recognition by the I.M.Y.R.U. of Scotland as a separate country, and consequent withdrawal of Scottish Clubs from the M.Y.A., left the latter body with fifty-three associated clubs. Of these, according to the M.Y.A. fixture list, twenty-two clubs in all sail A-Class, thirty-nine 10-Raters, nine 6-Metres, forty-two M-Class, and thirty-four 36 in. Restricted class. Actually I know of two more large clubs which 258 Championship, was found completely ineffective, since there is nothing to prevent an individual model yachtsman belonging to several clubs, and entering through any of them. Hence this change is unlikely to make any real difference in the number of entries for National events, though it may result in a lesser number of M.Y. Clubs apparently taking part. I wonder whether many model yachtsmen realise how much work is involved in arranging the M.Y.A. Fixture List? Or in the normal routine jobs entailed by running the Association? In order to keep the wheels turning, it is necessary for a number of “back-room boys” to devote themselves to administrative work. In most cases, these gentlemen have entered the sport to sail and race, but when they have perceived the need of officers to organise the sport, they have unselfishly resigned their own pleasure in order to work for the benefit of their fellow model yachtsmen, and the sport in general. I am, at the moment, thinking particularly of the M.Y.A. Officers, in particular the Chairman, Secretary and Treasurer, but in every district and every M.Y. Club there are individuals who devote much of their time and energy to the organisation of our sport. Thanks to the work put in by these gentlemen during the winter, our summer sport now lies ahead of us. * * * * In my December “talk” on the subject of yacht design I wrote: “Almost the only incontrovertible axiom is that perfect hull balance is essential, and that this results from volumetric balance.” It has been suggested that volumetric balance does not of necessity ensure a balanced hull. and that this can only be ensured by using the late Admiral Turner’s M/C Shelf system of balance. Now, by no means every designer of note, either of yachts or models believes implicitly in the M/C Shelf system of balance, or in the Admiral’s theory of rolling movement, on which it is based. At the same time, nobody denies that boats, whose designs conform to the M/C Shelf theory, prove balanced in practice. It must not be forgotten, however, that the Admiral himself stated that good volumetric balance is the first requisite towards hull (Continued on page 257) —