- Sea Mew – First Serious Catamaran Model Design

- Why It’s Important: Catamarans gained popularity in full-size yacht racing; Sea Mew brings this concept to model yachting. Offers a chance to compare catamaran performance with conventional racing yachts.

- Displacement: ~5 lb (much lighter than a 36R yacht at 12 lb).

- Sail area: ~500 sq. in. (vs. 800 sq. in. for 36R).

- Beam: 18 in., giving excellent stability.

- Construction: straightforward; hull sides and bulkheads ensure alignment.

- Rig: conventional mast with fore/backstays forming a pyramid; diamond stays prevent side whip.

- Performance Notes: May allow removal of lead ballast due to wide beam.

- Could carry more sail in light airs—future experimentation expected.

- Lessons from Sceptre (America’s Cup Failure)

- Columbia (USA) outperformed Sceptre (UK) due to superior design, not crew or gear.

- Suspected flaws in Sceptre: Thick keel and garboards → deep V-section. Poor harmony between bow and stern. Heavy wave formation → high resistance.

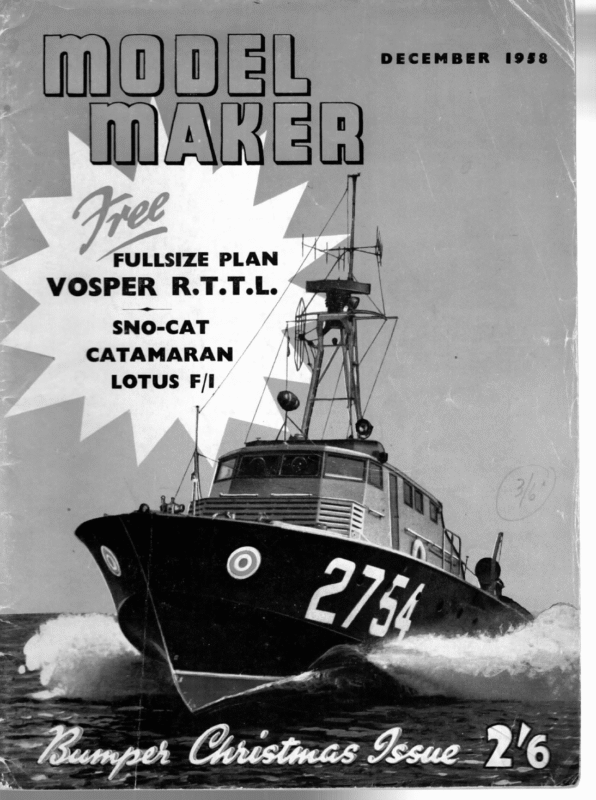

= MANE FULLSIZE PLAN VOSPER R.T.T.L. “ SNO-CAT CATAMARAN LOTUS F/I idiia

Ti ! : MODEL MAKER) model principles provided sufficient data to ensure satisfactory performance with Sea Cat, Vic Smeed offers yachtsmen SEA MEW the first ‘serious’ Catamaran design for exciting sailing ITH the “discovery” of the catamaran by the full-size yacht types, and the tremendous publicity received by such craft on a national scale, it is hardly surprising that modellers should begin to show an interest in the possibilities of a cat. To the best of our knowledge the only cat model so far published (apart from very small examples in this magazine, and two smallish kit models) is the 30 in. model Sea Cat in Model Maker Manual. Although of very simple form, this model performs very satisfactorily, and it is therefore safe to embody many of the principal features in Sea Mew, albeit this is a larger, nicer-looking, and altogether more advanced design. Since we are moving into what is virtually a new model field, there is little previous experience to draw on; however, a study of successful full-size craft—the Amateur Yacht Research Society bulletins are perhaps the most helpful—plus applicable basic sailing and logical development of these ideas has produced Sea Mew. Perhaps the greatest value of the design is that it will provide a model which can be compared directly with conventional racing yachts, and any builder who arrives at the pondside with this model when any normal M.Y.A. 36in. yachts are afloat can be assured of an extremely live interest from all present! It would naturally be foolish to suggest that Sea Mew exploits the catamaran configuration to the full, because we simply don’t know. She could probably carry much more sail, especially in light airs, and we may eventually have to change our ideas on hull shapes, length/beam ratios, displacement, etc., but nevertheless we believe that she incorporates just about everything that is definitely known at the present time. After all, we’ve got to make a start somewhere, and in ten years’ time we may know enough to say that single central fins and rudders are superior, that bipod masts are better, that ballasted fins are unnecessary, that cats won’t point as high to windward but their speed offsets such a disadvantage; we may even have an official M.Y.A. class for them. At present, the only class in which they are permissible is the 10-rater, but a 6ft. cat would seem an awful waste if it wasn’t successful, which is probably why we haven’t seen one yet. The conventional 36R yacht weighs within an ounce or two of 12 1b. and carries, usually, about 800sq.in. of sail; Sea Mew’s sailplan indicates slightly under 500 sq. in., but on the other hand the displacement is only 5lb., and this is variable since, with an effective 18 in. beam, it would take a fair blow to push the leeward hull under or lift the windward one, and it might therefore be possible to dispense with the lead on each fin altogether. Constructionally, Sea Mew offers no problems. If the four hull sides are carefully fitted with the din. sq. framing and the bulkheads accurately cut, no problem of misalignment can arise in the individual hulls. The rig is pretty conventional, except that no shrouds are necessary. The fore and backstays form a pyramid adequately staying the mast from all directions; to obviate side whip a diamond stay arrangement is also fitted. For portability the entire craft strikes down by undoing fourteen nuts (sixteen including the rudders, if these are removed) and slacking off the four stay turnbuckles. It can be re- 604

DECEMBER, [aay Bac me DEsickeo BF SEA MEW = Sneed a op RASS LOC J 4 ass Tv STANDING \ ie MIGGING (Fonestars, BacestaTS face ptt CIAMOMD STAYS) “ ee e¢ XSg oe wiMaAMOGANT ETC er so N 1} | \ : JUMPER STRUT, 226 BRAS . z ao |\ AX : pagel beg saebeaee ole waneR PLANSAas SoOseeen im —— eS ‘ Catewanan 1958 , r mmuace Soba * sou0e “ okey | i & PROM 22-24 SmC STAINLESS | saceumt 6 Ys wine iran, wae | ” 7 DRESSMAKERS HOOKS & AETED on CPEMED EveRY 4° TO LUPPS OF BOTH Sant ‘ SBA BOLTS EVERY O° Ur mi 13 dp EADS PCKED TO RETAW teh: wily SorTee somews (TunBuceits) Om PORE & BACESTAYS, enous tunes ‘s Yo x 20 4″ yh BACHMAUL EYE 7 *2 se H TRACK (ines 8 ee | Lear | a CEES ;H L-MasT ster Wine. avert ‘Vs wine icoiaade ‘Wor erm vemvicas tocinc sta of Ye muy, :;1 Pes Sag y TLLEa river iv 4 om zm pes binant se vee oe ap i — cur reow ¢Uatam ase | mansi (= ll 2 came n’t” seevee iin nvno 8 40 pata raaut on mr HOES Us Woo «01h TO acicw oy, ve CLYEMT BULEMEAOS TO TRAwES EEL © DE mm PREFABRICATED CONSTRUCTION Avicnwent ~ ASSURES ~> > Witcao swear (aremox “4 083) om 31 OF CaCw WEEK mb0eGO OBECME PLAMeine acme CaaCtT et TR, ’ Pr CEG mar Banos Tete Stew a SHkmnnitee 7 nD BOLTED om PLACE CPETYy assembled in a few minutes, and is self-aligning. As far as cost goes, the most expensive items are likely to be the mast and cross-tubes. If no discarded T V aerial is suitable, H. Rollet and Co. can supply these. Dimensions are not too critical, and because of likelihood of variation in these and items such as vane gear, it is suggested that before finish painting the model is assembled and floated, the lead sheets being strapped in place with rubber bands and moved or trimmed slightly to obtain correct trim. 605

DECEMBER, ( “7 UCKER’S TOPICAL TALKS LESSSONS FROM SCEPTRE ) t is interesting to note that Olin Stephens, the American designer of Columbia, the successful defender of the ‘‘America’s Cup”, declined to publish her lines. Almost the only facts about Columbia that I have been able to glean are that she is of lighter displacement than her British rival Sceptre, and was superior to her on all points of sailing in all weights of wind. As a general rule, both in models and full-sized craft, contestants are so closely matched as regards design that the major factor in a yacht’s success or otherwise is the ability of skipper and crew. In the case of these races, however, Sceptre’s personnel was in no way inferior to Columbia’s, while sails and gear were at least as good. It was simply that the American designer did a better job than the British. Of course, the Americans had four boats from which to choose a defender. It is, however, interesting to recall that among the four the second choice was the pre-war Vim, also an Olin Stephens 7 = creation. Since the War, British designers have had very little opportunity to design large racing yachts, the pre-war Evaine was the only trial horse we could provide for our Challenger. Nevertheless we should have done better. Without the lines and dimensions of the two yachts it is difficult to make a true comparison between the boats in order to assess the reason for the latter’s superiority. If the two designs were of equal technical merit, then our defeat must be ascribed to a better choice of dimensions under the rating rule. Nevertheless, I have the feeling that an inferior design was the main cause of Sceptre’s failure. When I saw the published photographs of Sceptre before her launch, it seemed to me that in order to combine moderate beam and heavy displacement, the designer had given her a very thick keel, filled in the garboards unduly. Asa result, she had a deep V-section. Without analysing her lines in detail, it is impossible to be absolutely certain, but she also appeared to combine a rather weak, short forward body and a long, heavy stern. In other words, bow and stern did not match. This impression was confirmed by photographs of her under sail, in which she appeared by the head, both close-hauled and off the wind. A yacht’s shape can be judged fairly accurately from her wave-throw, and Sceptre’s not only revealed this lack of harmony between her ends, but also that she had a very deep wave formation. The latter was, of course, an indication that she was by no means easily driven. It may be contended that Sceptre was fully tank-tested, but I have always been a trifle sceptical about these results, especially as regards water resistance. Results obtained by towing are not necessarily the same as when the vessel is self-propelled under sail, because both wind and water have to be taken into account. On the other hand, streamlining can be accurately gauged by waterstream observation in the tank. Hence the discrepancy between Sceptre’s bow and stern should have been apparent, also the depth of the trough between her bow-wave and stern-wave. From these it should have been possible to foretell an unsatisfactory performance. 1958 For many years Mr. W. J. Daniels has contended that the only satisfactory model test for yachts is an actual sailing test, but from these tests it must not be inferred that a model design that is satisfactory will necessarily enlarge into a satisfactory full-sized yacht. The truth is that every yacht, whether full-sized or model, must be designed for the size she is to be built. Thus a model 6-m. would be unlikely to enlarge to a good 6-m. yacht. Likewise a crack 6-m. yacht would be unlikely to enlarge to a winning 12-m. yacht. On the other hand, two scale models, both of yachts designed as 12-m., might provide valuable guidance as to the respective merits of the two designs, under if tested steering gears. sail with equivalent vane In a recent article published in this magazine, it was contended that model yacht designers are behind designers of full-scale displacement type yachts. How wrong this contention is can be judged by the costly fiasco of Sceptre’s challenge for the ‘America’s Cup”. Let us hope that another Challenge will not be issued until we are able to design a yacht that has a reasonable chance of success. Actually, a failure can be as valuable a lesson as a success, and the wise man tries to learn not only from his own mistakes, but also from those of other people. Yet all experienced designers know the importance of complete harmony between the fore-body and after-body of a yacht of the displacement type. They also appreciate the danger of making keels and garboards over-thick, and thus impeding the flow of water through the garboard angle. After all, the design of sailing craft, as we know it today, has been evolved by hundreds of years of experiment, of failure and success. There are many features of design for which we have as yet no scientific explanaYet we know that certain forms unfailingly tion. produce certain results, and no amount of pseudoscientific jargon alters these facts. The wise thing is to accept them as axioms, rather than repeat the blunders of yesterday! Rightly or wrongly, after about forty years during which I have made several hundred designs, I have come to the conclusion that the most important part of the designer’s work lies in the elimination of unwanted steering effects and similar vices. His next important job is the careful streamlining of his lines, which can have a bearing on the elimination of unwanted steering effects. In connection with the above, it must not be forgotten that many beneficial features become detrimental if over-done. It is not sufficient in itself to produce a technically good design. In addition, the selection of dimensions and proportions is equally important. As regards the latter point, I have often fallen into the error of trying to produce a good “all-round” boat, that will perform satisfactorily in either light or heavy weather. If one is successful, one then produces a boat that is always in the picture, but on a light day cannot quite hold the out-and-out light-weather boat, and in heavy winds is just a trifle inferior to the heavy weather one. Possibly your “all-round’’ yacht will gain a longer string of prize flags than either the light-weather or heavy-weather cracks, but her flags will be 2nds and 3rds to the other boat’s Ists. Consequently it probably pays to go for either a light- or heavy-weather craft, according to the weight of wind normally encountered on her home waters, or during the events she is likely to compete in. * * * * * * In conclusion, may I take this opportunity to wish all my readers a very happy Christmas and a prosperous New Year. 615 me