A few weeks ago, the writer of these lines formed one of a huge crowd on the Thames Embankment. It was damp and chill, a fine mist fell, the roadway was ankle deep in mud, yet thousands of people stood motionless for hours watching two tiny boats moving slowly across a screen. Cold and wet and discomfort were forgotten as they cheered the Shamrock when she drew ahead, or groaned as Columbia went to the front. News boys were shouting “Declaration of War!” England was entering on the greatest fight, the most momentous struggle, of forty years, but the crowd forgot it all for a yacht race. Foreigners came by, shrugged their shoulders, murmured some flattering allusion to “mad Englishmen,” and passed along, not perceiving the real meaning of what they saw, nor understanding that the crowd typified in its own way the pulse of the race.

To begin an article on the toy boats of London by reference to the two great yachts of England and America, most swift and shapely of all things that move wind-driven on the sea, may seem a descent from the sublime to the ridiculous, the bringing into life a mouse from the throes of the mountain. And yet, perhaps, the subjects are not very wide asunder.

The interest excited by the America Cup race was due, we take it, to it being a race between yachts. There was, indeed, the spirit of rivalry which all sporting contests arouse in our sport-loving people, but underlying it all was that which we have termed the impulse of race—the deeply seated love of the sea, the fine intolerance of finding a superior on the element we hold to be our own. And the same lesson may be learnt on every stretch of coast, on every reach of river, on every pond. For it is most certain that there is something in the English blood—something that perhaps has come to us from our far-off Viking ancestry—that draws the English to the sea. It is towards the sea that the dreams and desires of boyhood go—the sea with its wonders, its adventures and its triumphs; the sea life presents itself as the acme of human happiness, With the political and commercial results of this we are not concerned—they are written in the world’s history; we offer it in explanation of the passion of the Englishman for boats great and small.

It is a passion that comes early to maturity, To the small boy, scarcely emancipated from the perambulator, comes the yearning for a boat all his own and therewith, too, this first lesson in thrift. Aided by a money-box, which no human ingenuity will open, he saves and saves until the day when he too can launch his tiny barque upon the Round Pond.

He is first but a timid mariner, suffering not his precious boat to venture beyond the restraining limits of a cord. But hardihood arrives with age and habit, until at least comes the supreme moment when he trims the sail with unskilful hand and sends forth the tiny craft on her first real voyage.

How anxiously he follows her erratic course, trembling when she lies down under a sudden squall, triumphant when her dripping sails emerge from the water, his whole heart going with her as she faces the perils of that great ocean; how eagerly he toddles round to meet her, glowing with all of the pride of a great and successful voyage. It is a pleasing sight to be seen in Kensington Gardens on any day of summer and on many a day in winter, too. There are tragic scenes also, scenes of shipwreck, when the vessel, insufficiently ballasted, is overcome by the storm and goes down all standing; times when the vessel is boarded by young ducks as by pirates, and in fancy he sees her being borne away to their lair; dire collisions, when boats locked in close embrace, revolve in the centre of the pond, refusing to come to shore, and their owners are borne away shrieking at their bereavement. But the park keepers are kindly, and the ships survive to make many another crossing.

This is the earliest stage of his nautical evolution, when he is, so to say, at the mercy of the winds, and chance alone directs his vessel’s course. As he advances, the Arcana of boat sailing unfold themselves, he begins to distinguish between running, reaching, and beating, he pierces the mysteries of going broad or close-hauled. He lays his course for some definite port, and great is his glory if he manages, even approximately, to attain it. He becomes the owner of a larger boat, he picks up wrinkles from the master of the art, and with increasing knowledge come wider ambitions. He goes some summer to the sea, he sees for the first time the dainty white-winged yachts skim across the broad expanse of blue, and dreams of the time when he too can own a yacht, feeling that with such a possession future would have no more to give him. It is curious the reverence with which we regard the owner of a yacht, all of us of every age.It makes no difference whether she is a stately palace of 600 tons or a tiny speck whose cabin is a tight fit for one, the great fact remains that she is a yacht. To own her raises a man in our esteem, not because it argues in him superior wealth, but because regarding the sea as our own dominion and property, we simply feel that he has in some sort come into his heritage. Let us hope that the boyish dreamer will one day come into it too.

But it is not for every man to get to Corinth. The obstacles in the way are many—want of means family ties, the claims of business, lack of opportunity. A sea-going yacht must remain a dream for the man as for the boy, but the passion which prompts it remains undiminished, and finds its ven in the building and sailing of model yachts.

Model yacht sailing is not a mere childish waste of time, as some scornfully pretend but a serious undertaking which involves great dexterity and skill in designer builder, and navigator, and which is a solid livelihood to very many people. There are, so far as we know, no accurate statistics as to the extent and value of the toy fleets of England, but the sum would be very astonishing were it set forth in figures. On a fine day as many as eighty boats may be seen together on the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens, varying in value from a couple of skillings to thirty pounds. And the same thing, though on a lesser scale, may be seen throughout the country. This however, opens up too large a field of speculation—we would devote ourselves rather to the subject as it affects London.

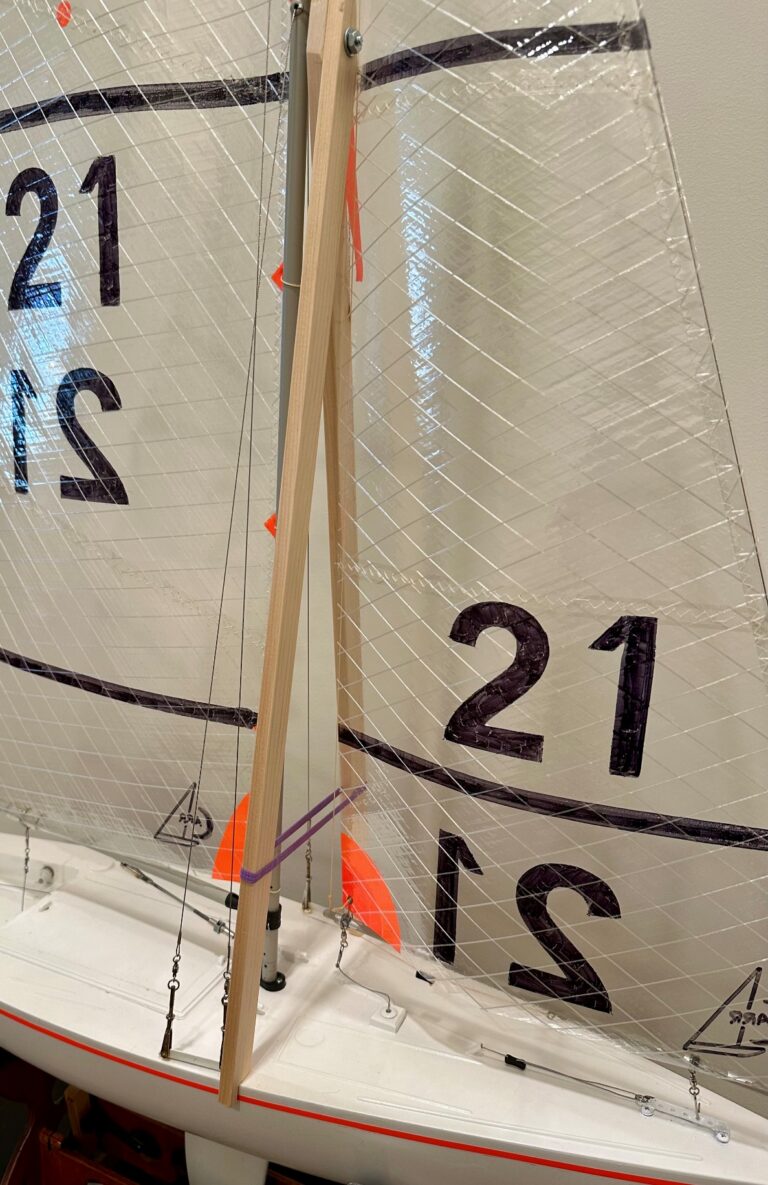

There are in the metropolis many model yacht clubs, whose members sail on the water at Clapham, Battersea Park, the Serpentine, and indeed whatever suitable water can be found. But the Round Pond may perhaps be considered the Cowes of the Starting for the beat home. metropolitan yacht world. Behind the Orangery is a low building hidden by greenery and surmounted by a flagstaff. It is the hope of two clubs, the London Model Yacht Club and the Model Yacht Sailing Association. Entering, we find ourselves in a veritable dockyard. There are long rows of yachts fixed in cradles, their sails hanging loose, yachts of every shape and pattern, carrying in everything but size. We see boats like skimming dishes fitted with single or double fins, boats with long shallow keels, and boats with keels short and wedge-haped. There is a controversy of long standing as to the respective merits of their builds, and though keeps are now in fashion the champions of the fins are not silent. They point to the speed of their boats, to which their opponents reply that they are less steady and trustworthy, too apt, as it were, to be blown about by every wind of doctrine. Far be it from us to express our opinions or to intervene in the sometimes heated discussions of the rival theorists.

But though they differ in their lines and build—some being hollowed from the solid block and others built with ribs and planking—in size the boats of the two clubs are similar. Those of the London are the larger, 15-raters, while the M.Y.S.A. are content with 10-raters. As a fact the hulls of these two ratings do not differ in the proportion of three to two. The average water-line of a 15 is about 44 in to 45 in, that of a 10 about 38 in. The dimension is, indeed, somewhat arbitrary, and is intended for the regulation of the sail area. The formula for this is simple: 6000 ⨉ the rating ÷ the water-line. Thus in a 15-rater of 45 in waterline, you divide 90,000 by 45 and you get your sail arena 2,000 square inches.

The care and trouble involved in the building of one of these boats is very great. Mr. Fife never gave more thought to the planning of one of his masterpieces than do the designers of a model yacht to thinking out her lines. New experiments are always being tried, and their results are eagerly awaited and hotly, sometimes even acrimoniously, discussed. And when the design is complete there remains the work of the builder, work requiring the highest skill and care. As an example of this a builder told the writer that when he placed his boat in the water fully equipped her displacement was correct to a sixteenth of an inch. Cutting and fitting of the sails too is a matter of the highest importance, seeing that there is no guiding hand at the helm, and that therefore the steadiness of the boat depends to a great extend on the perfection of her sails. At last, after many weeks of anxious work the new boat is christened, passed by the official measurer, and ready to go forth to do battle with her peers.

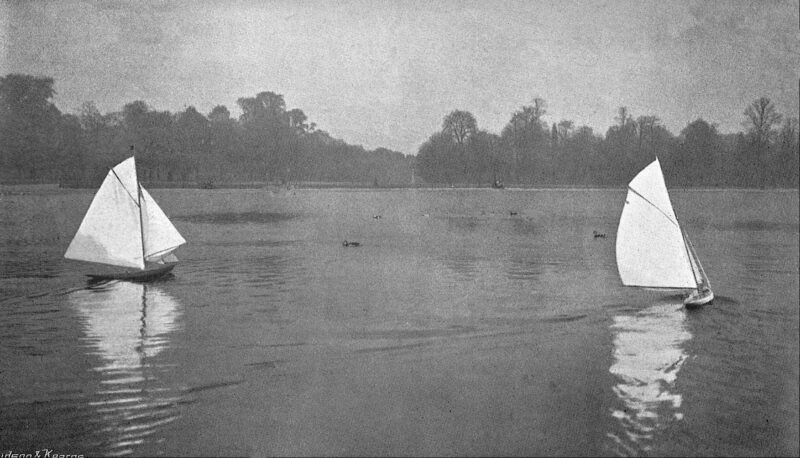

Let us assist at one of the regattas of the London Model Yacht Club, to whose commodore and members the writer’s thanks are due for their kindly interest and assistance in the preparation of this article. It is a quiet October day, the clouds move softly before a westerly breeze, there are quick alternations of light and shade, The boats are grouped on the green grass, while their owners anxiously study the capricious airs, Five boats are to compete today—Ailsa, the crack vessel of the club; May, the property of the commodore; Isolde, Eldred, and Topsy, the latter a new boat whose capabilities are not yet known.

The matches are sailed in heats, each boat sailing two boards against each of her rivals one board to windward and one to leeward, three points being awarded for the beat and two for the run. They start first for the run, some under their ordinary sail, some with spinnakers. But spinnakers are not much in favour on the Round Pond. For though the trees surrounding it are cut converging alleys, down which as through tunnels come breezes varying in strength and direction, baffling the best-meant efforts of the navigator.

Accordingly too often the spinnaker is but a delusion and a snare, which the more wary avoid, contenting themselves with the artful contrivances in the way of guys and gybing lines, and a nice calculation as to the weighting of the rudder. Grouped on the green grass.

In running before the wind a large rudder is used, with sockets for the introduction of leaden weights; in beating a tiny unweighted wooden rudder is employed. The sailing rules are simple. Each member has a bamboo pole of a certain length with which he may put his boat about when in beating she approaches the shore. This is the prettiest work of all, especially in a close-fought struggle near the winning line and productive sometimes of risky positions, as maybe seen in our photographs. If in running a boat touches land, her trim must be altered—the commodore is depicted doing this service to the May. And now the boats are off, followed by their owners ready to render them any necessary assistance. An easy, even a lazy, task this if the wind be light, but when it sweeps down in fierce gists it is an exhilarating sight to see a gentleman no longer young nor slim rushing wildly round the pond, one eye fixed on his boat, the other on the children and perambulators that beset his path. It is a fine trial for the temper this racing on such water as the Round Pond, when one’s boat has secured a good lead and then gets becalmed in the lee of the trees, or when she falls foul of some wretched craft whose topmast barely reaches her bowsprit, and revolves aimlessly in mid-sea. Very trying, too is it in a beat when a gust comes down some alley and she luffs up and suddenly with her way gone and all her sales ashake, Small wonder, then that we see in the human competitors alternations of hope and despair, and her outburst of genial triumph or sometimes, be it whispered, the faint echo of an execration. It is really very exciting, The last heat of the day has been reached, and May and Ailsa are equal upon points, and in front of all others, The two yachts run neck and neck before the wind. Their owners are old hands, up to every move of the game, every vagary of the fickle breeze. First one catches the wind and leads, loses it and falls behind. And then a dreadful thing happens, as a quite unexpected slant of wind catches May, she falls off, and Ailsa glides ahead, never to be caught again, Still the three points to be earned on the beat to windward may yet give May the victory. The wind has backed to the southward, sheets are easing away a little in order, if possible, to make the winning line on one tack. Ailsa has the windward station and opens up a lead, Three-parts of the way across May closes up the gap, Ailsa loses the wind, and falls away to leeward as May comes up under her stern to the weather berth. Forty yards from the line May leads, in 10 yards more Ailsa head her, then May goes to the front once more; there are only a few feet yet to go, and then Ailsa gets a lucky puff, slips by, and wins by a bare length, asserting once more her claim to be considered the champion of the club.

And the dusk closes in, the shadows thicken under the trees and in the club-room the members meet to discuss things nautical and perhaps something still more soothing, and to fight out once more their rival theories, backing their opinions with divers challenges and—the Englishman’s final argument—a wager. For all are enthusiasts—the youth with large ambitions, the lawyer and merchant who beside the water forget courts and ledgers, the old sea captain for whom in the mimic sports the shadow on the dial goes, while there comes to him a whiff of the merry sea breeze he knew and loved so well, And long may the English people love the sea.