by Walter K Moss

It would be a rare case indeed should a model yacht be dropped into the water for the first time, or after alterations have been made, to discover that it sailed perfectly at its maximum speed. Such things may happen as often as the experience of Mrs. Dionne . . . and from that you can figure what your chances are of having such an unusual experience.

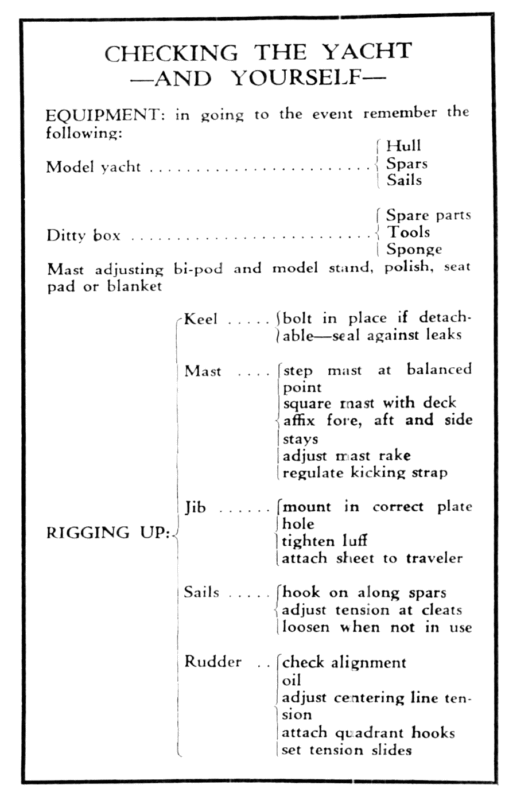

Most model sailing craft, especially racing models, are equipped with sliding mast steps and adjustable jib stay plates, and can, therefore, be made to sail in a satisfactory fashion by undergoing a process called “tuning-up.” Tuning a well designed and constructed racing yacht is a matter of balance between the sails, the rake and position of the mast, and the trim of the sheets; it is usually the first consideration if the craft is new, or if any changes have been made which alter the center of effort or the center of lateral resistance in an old boat. Arriving at the proper balance is the result of experiment and study of the reactions of the model in the water, but when once attained it will assure the best possible performance from your yacht.

This setting should be carefully noted and repeated each time the model is rigged. In fact when you have determined the exact position of the mast step and stay plates, these can be reduced to the most simple pin and eye forms to save unnecessary weight.

Tuning a yacht is not as complicated as its explanation may appear, although to explain the process which should be followed will require quite a number of words – many of which the more experienced will probably skip.

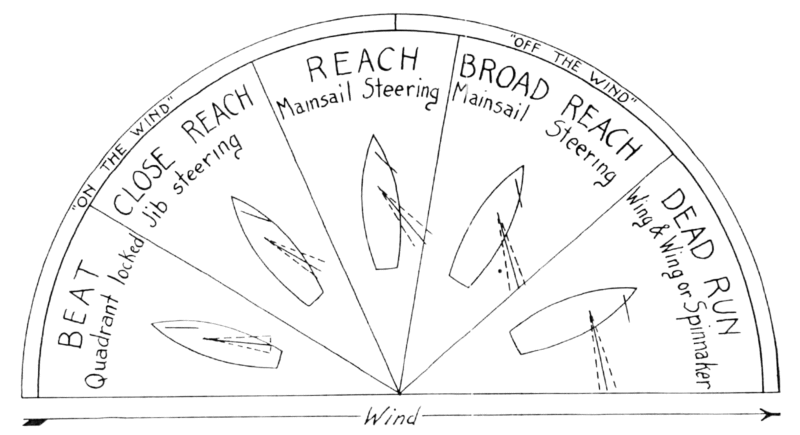

A balanced boat is one which will hold its course and also attain a good speed with the sails closely sheeted, when beating into, and about 4 points off the wind. No yacht can sail directly into the wind but must tack side to side to go to windward, and four points would place the hull at about a 30° angle to the direction of the wind. When thus adjusted both tacks should be accomplished at the same angle.

Step the mast square with the deck and about one inch ahead of the estimated center of lateral resistance, adjust the sheets so that both the jib and mainsail are at a 15° angle with the center line on the deck, lock the rudder in its center position with the tension slides; place the craft in the water nosed into the wind, but with the sails filled and gently push it

away . . . NOW WATCH ITS ACTION!

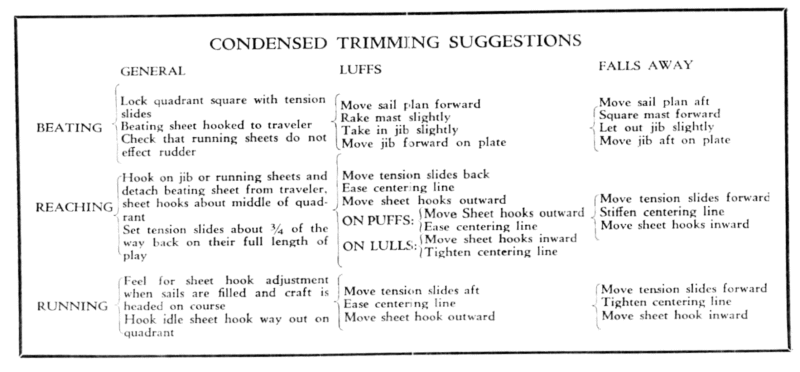

If it falls away from the wind, move the mast ferrule aft on the step; if it heads into the wind and the sails begin to flap, move the mast ferrule forward. In making these changes, be sure to adjust the stays simultaneously – fore and aft – so as not to alter the rake of the mast in its new position. When the yacht holds the course indicated above, or approximately such a course, you have arrived at the proper balance with regard to the deck fittings. Should there be a slight tendency to luff at this stage, two further adjustments can be made: rake the mast slightly (meaning to take up a bit on the back stay and let out a bit on the fore stay), or sheet the jib in at a little less angle than the mainsail. These procedures sometimes produce an intermittent flutter in the leach of the mainsail, but it will promptly be pulled out and keep both sails working at their maximum capacity without perceptible change in the course of the yacht.

Now is the time to experiment with tightened or slackened sail surfaces and side stays. Some yachts perform better one way and some another, but in the majority of cases it will be found that a little flow in the sail – very little – will increase the speed over a flat, tight surface.

If a boat goes to leeward (drifts sideways) on a beat, it is because the lateral resistance is not sufficient to offset the side impulse of the sail plan. Ease away the sheets until it is able to go where it is pointing. Remember that the lateral resistance increases with the speed of the hull through the water, and that in heavier winds a yacht can be pointed much higher into the wind without “crabbing.” Any windward beat can now be accomplished by changes made in sheeting the sails, and any reach or run by the same with the addition of the rudder controls. As the sails are let further out it will be found that a course will be followed further off the wind, until finally it is necessary to help the craft with a “weather helm,” which will help hold the nose down wind. The beating sheet need be no longer than will permit adjustments to this point as the running lines will now take over the job. If you have noted the positions of the beating sheet bowser on the boom calibrations for the various courses with relation to the direction of the wind, you will be able to predetermine the probable course of your yacht by repeating these settings.

Following the course of a yacht around half an orbit from a beat to a run you now arrive at a close reach, and many skippers prefer to use jib steering in this case as the strain is not great and lighter alterations are sufficient to hold the boat on its course. Hook the bridle to the jib sheet and play it out to the proper point for the desired course. In reaching, the jib functions as a propulsion unit as well as a balancing unit. However, there is only a small range of directions on which their steering is effective, and as soon as the stem can no longer be held downwind, the boom running sheets will have to be brought into action and the jib sheet re-attached to the traveler. Do not attempt to operate the rudder with both the jib and mainsail sheets simultaneously.

With the quadrant centering line tautened only enough to pull the rudder square, place the running line hooks in the middle holes on the quadrant face on their respective sides and adjust the tension slides to a position a little back of their full play fore and aft. Head the yacht on its proper course and with the running line bowser, set the sails just short of “spilling” the wind—and your craft is ready for a reach or a run. The writer has found this much more difficult to control than a beat, although fewer points result from such a leg won in a race. As a precaution, the idle sheet can be hooked far out on the quadrant to jibe the boat back on its course if the correct tension settings have not been made and the boom flies over. Again the actions must be closely observed and adjustments made to counteract undesirable performances. Should a tendency be noted to head up into the wind, more leverage is necessary and the quadrant hook can be moved out a hole or so; if the tendency is to run further downwind, reduce the leverage by moving the hook toward the center. In a steady wind some point will be found at which the rudder action will equalize the turning action of the mainsail— and the course will he held.

If the velocity of the wind was always the same it would be unnecessary to provide further adjustments; but as this is not the case, provision has been made to stiffen or ease the rubber tension by tightening or loosening the centering line, by changing the position of the quadrant hooks and by moving the tension slides forward and backward.

Now, again—note the behavior of the craft. Does it drop to leeward, move the slides forward or tighten the tension of the rubber; does it go to windward, move the slides back or ease the centering line. The degree of the adjustments depends upon the response, but never be “heavy-handed.” It isn’t necessary and you may create just the opposite L condition which will likewise have to be corrected and necessitate several re-trims and the consequent waste of time. Again some combination of adjustments will be found at which the model can be made to hold a more or less steady course.

Lulls and puffs in the wind are one of the most annoying conditions with which the skipper must contend, as they constantly alter the amount of “heel,” thereby encouraging a change in the course of the yacht. Correctly cut sails for a well designed hull will go a long way toward offsetting this trouble, but no design has yet been created, and probably never will, in which the center of effort will constantly balance the center of lateral resistance under the many situations which develop during the course of a leg.

With the lengthening of the waterline as the result of a puff, the lateral resistance increases and the prow sets up greater resistance proportionately, thereby increasing the tendency to luff. Although the center of effort in the sails has moved forward under the new angle, only a semblance of balance is maintained and adjustments are necessary to automatically overcome these discrepancies. This is where your individual ability as a skipper comes to the front . . ; if you hit on the ideal balance more often than you miss, you’ll be an outstanding skipper.

At this point it’s a matter of feel rather than instructions, but if the model has a tendency to luff on puffs: move the quadrant hook out, ease the centering line or advance the tension slides.

When you have gained the “feel” of your yacht and the various adjustments can be made more or less instinctively, for racing purposes there is the matter of “looping” with which to become acquainted. This is generally used on pool racing where the craft is to be sent part way out on the pool, gybe, and return on a longer tack. To accomplish this it 1s necessary to use a beating gy c which shortens the setting of the sails on one tack, and lengthens them on the other. The beating gye is always hooked on the weather side in this maneuver when the craft leaves the shore and the jib is hooked on the lee side of a three place traveler to help head the boat into the wind. The yacht is released off the wind and will gradually be pulled into a luff some distance from the bank where the wind will catch it for the longer leg. If it cornes about too quickly release the gye a bit, or if it fails to come about take in on the gye.

These adjustments are best determined by experiment, as a slight miscalculation will nullify your efforts. A beating gye can also be used to advantage in a light wind when the sheets are closehauled, and in this case should be put on the lee side. In the event that a puff turns the craft onto the other tack and off the course, the beating gye will function and return the model on its previous tack.

Suggestions on the use of a spinnaker are given with hesitancy, inasmuch as considerable grief can be encountered unless it is properly handled under ideal conditions. In a steady wind it is invaluable on a run, but where the velocity varies it is quite liable to become fouled. This sail should be loosely sheeted to permit bagginess and exert the lifting effect on the stem which it develops. It is always rigged on the opposite side from the mainsail and provision should be made for quickly releasing it altogether should the yacht “get by the lee” (when the wind and the mainsail are on the same side of the craft).

A spinnaker can be set when the wind is about 30° abaft the beam and should be well forward at this time: as the run becomes more of a “dead tail ender” and the boom ‘s eased out, the spinnaker aft-haul is pulled in, but never to the point where it is exactly square with the hull (about one point ahead of the beam should be the maximum). Of course, the running sheets on the quadrant still control the course. On a “dead run” without a spinnaker, the jib is of little avail, but ‘t can be hooked on to the bridle to correct the course if a hard puff should suddenly “head” the yacht as it will be affected by the wind before the mainsail functions, or weaken the pull of the running sheets by counteracting.

It is impossible to cover the multitude of situations which may be encountered when sailing a model yacht—each has its own solution and must necessarily be worked out by the skipper himself and the experience he has gained from previous voyages. Mentally noting the re-actions to adjustments, and subsequently bearing them in mind when making changes, is the real secret to a successful racing career.