- Editorial – Assistant Editor’s closing remarks on stewardship of the magazine, appeal for funds

- British “A”‑Class Championship & International Race Announcement (Fleetwood) – Official notice

- Building a Planked Hull (conclusion) – Step‑by‑step practical guidance on finishing, fitting ribs

- 10‑Rater Championship at Eastbourne – Comprehensive report on the first southern‑hosted championship,

- Our Scottish Page – Commentary on Scottish regattas, club rivalries

- American News – Reports on U.S. A‑class and Marblehead events, debates on class size

- News from Éire – Cork and Lough Mahon activity, cup competitions, weed‑related sailing difficulties

- Club Reports (UK‑wide) – Match results, championships, junior development, membership growth

- Wooden Merchant‑Ship Building (continuation) – Detailed glossary and explanation

- Robertson Cup Challenge Fund – Formal appeal to British and Irish clubs and individuals to support

- Fixture Lists & Upcoming Events – National and regional regatta schedules, championship dates

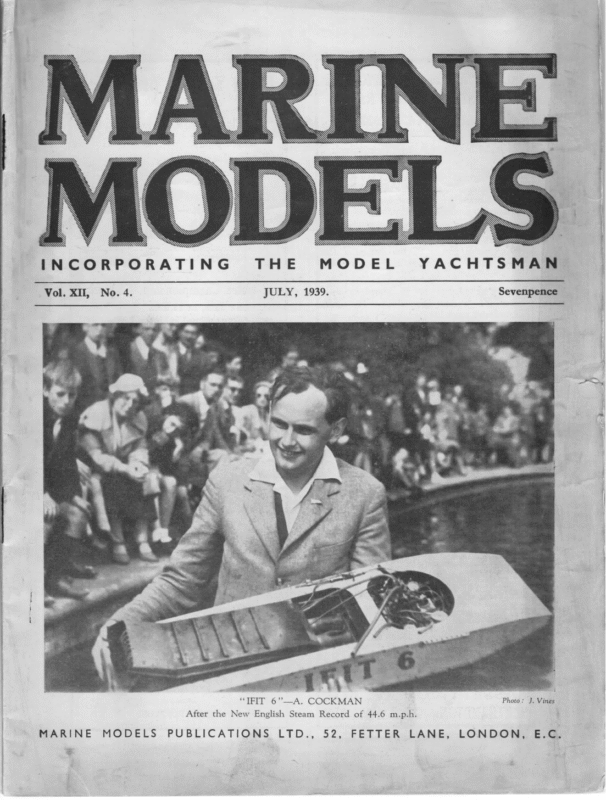

CAAA AeA NAdAQAQaga 8 Y \ lly “li os Z RR. WS “Um Yy VldsddidddddaWy S CMLL Y No. 4. THE vs ZY TEL epaeccccccclaUsd N MMMM LLL ba ie dd <7 %y%y y Wy 7 Za Zl WLLL Gyy LSE STLE rN SSNS WSS SSS SS ae INCORPORATING Vol. XII, SSS. y yA G WUMMIUMILLLEEEE G MO MEN MODEL YACHTSMAN Sevenpence JULY, 1939. 1 “TFIT 6”—A. COCKMAN Photo: J. Vines After the New English Steam Record of 44.6 m.p.h. MARINE MODELS PUBLICATIONS LTD., Dili, FETTER LANE, LONDON EvGe

BRITISH “A” Class CHAMPIONSHIP Model Yachting Association AND INTERNATIONAL RACE, FLEETWOOD, ‘“‘A”’ Class British & International Championships, Fleetwood. 1939. July 24th—August 2nd (inclusive). JULY 24th—29th, inc. Selection Trials and British “A” Class Owners/Skippers and Supporters are respectfully reminded that the M.Y.A. “A” Class Regatta Committee have made an appeal for donations to the Regatta Fund. Championship. JULY 30th. Practice Race—Challengers v. British Boats. If you have failed to send a donation, please do so at once. Skippers and Mates from five countries are to be the guests of the British Model Yachtsmen at Fleetwood for the International Race. Send your cheque or postal-order JULY 31st, AUGUST Ist and 2nd. International Monthly Cup. Race — The Yachting 12-metre Championship, Gourock. 0 Victor F. Wade, Esq., Hon. ‘Treasurer, Westminster Bank Limited, Blackpool. AUGUST 19th, at 11 a.m. (Not as printed in Fixture List). Regattas cost money, are you willing to help financially ? Broadhurst, St. Mary’s Lane, Cranham, Wm. M. CARPENTER, Upminster, Essex. NEW MODEL BOAT HULLS WHITE HEATHER ~ y Hon. Regatta Secretary. John H. Yorston, Hon. Secretary. Racing Model Yachts J. ALEXANDER & SONS 26, Victoria Parade, Ashton, Preston, Lancs. Expert Model Yacht Builders Three-quarter view, showing the smart stem and design of the three hull types. A (30 years’ experience) FITTINGS SPECIALISTS FINE SERIES OF HAND CARVED HULLS. Our experience has satisfied us that the hand carved hull is the best in the long run, and this range in two qualities, is, we feel, the best produced at the money. * Alexalight ’’? Metal Spars. Practical Sail Makers. Type !—Destroyer Hull—raised fore-castle type, from 24 in. long to 39 in. Accessories. Prices from IIs. 6d. to 35s. Type 2—Racing Motor Boat Hull, from 18 in. Prices from 5s. 6d. to 26s. 6d. Type 3—Liner Hull, 30 in. long. to 39 in. Send Stamp for Lists Price 24s. Racing Model Yachts Other interesting Ship Model Accessories are described in Bassett-Lowke New Ship Model Catalogue - S.5 6d. post free. WHITE HEATHER BASSETT-LOWKE, LTD. NORTHAMPTON sccscsesier: 28 corporation sires When repluing to Power Boat Hulls. Advertisers TRADE SUPPLIED please mention MARINE MODELS.

.) N Ny Nj INCO PORATING THE MODEL YACHTSMAN Vol. XII, No. 4 Published on the Seventh of each Month July, 1939 EDITORIAL A ND so we come to the end of our short term of office as Editor of MARINE Mopbe.s. It has been a pleasant four months making closer contact with many whom we already knew by name through these pages. A very big spot of praise and sincere thanks must go to those regular contributors who keep these pages and the sport generally, alive. We ask them one and all to accept our thanks through these columns in lieu of the personal letter which has been quite impossible these last few months. It may seem strange, but in point of fact your humble Assistant Editor has been abroad very nearly as much as your regular Editor. A few days at home, i.e., evenings, after office hours, is not a great deal of time to devote to shaping up a Magazine of this importance. Our powerboat readers are well catered for in this number, as, apart from the two technical articles by Mr. J. Vines and Mr. Kenneth G. Williams, we are including the first of this season’s reports and illustrations. The photograph of Mr. Cockman with his “ Ifit 6,” taken by our own Mr. Vines, takes pride of place this month. A worthy record of a splendid effort. Our readers are also asked to note and contribute to the fund being raised by the Hon. Sec. of the M.Y.A. to meet the expenses of sending representatives from this country over to the States to take part in the Robertson Cup Regatta, being held very shortly in Detroit. In the past we have been able to welcome many model yachtsmen from abroad. We are now being given the chance of sending our men to represent this country by way of a change. Don’t let the side down, chaps. Don’t let the side down. It was with great pleasure that we learned of the success of the 10-rater regatta at Eastbourne. Everyone who is able to attend came back with glowing reports of the success and splendid way in which the Eastbourne authorities arranged the pleasures and hospitalities for the local and visiting model yachtsmen. In the past, model yachting has been looked upon as a Cinderella sport, if a sport at all. Now we have not unimportant seaside towns relying on at least one big regatta per year as part of their season’s attractions, and if they do not get the assignment they have something to say about it. It looks good to us. Anyway, Eastbourne has a clear idea of what is going to happen and seems determined to get er share of it. Goed for you, Eastbourne. Before finally packing up, there is one small point we should like to clear up. In a round about way we have been told that Club News is subject to not a little favouritism and that certain clubs get long reports always inserted, and others get the blue pencil, if printed at all. The truth is that, during our tenure of office, all reports have been set up verbatim and not a word deleted except an, occasional line or paragraph to fit the page. Of course, the blue pencil has been used when bad taste has reared its head. And so fer the present I leave you.

82 MARINE M.P.A. MODELS INTERNATIONAL REGATTA Another successful International over: this time with the welcome face of M. Suzor among the competitors, who took the chance of bringing ‘‘Nickie’’ over, fitted with a new piston and untried. His first attempt showed that the old fire is still there, but it was not until his third try that he managed to achieve 38.6 m.p.h. After the first round, the placings were: Mr. Williams, of Bournville; Mr. Parris, of S. London, and Mr. Clark, of Victoria; and it was still anybody’s race, but the second round seemed to show that a few jets had been adjusted, for Mr. Rankine’s ‘‘Oigh Alba’’ got really going to get round in 23.48 secs., a speed of nearly 44 m.p.h. (After checking the length of line, his speed was over 44 m.p.h.) Mr. Williams did not have his second run, but came into second place; while Mr. Clark managed to displace Mr. Parris, and so retain third place—so the final placings were :— 1, ** Oigh Alba ’’ (Mr. Rankine, Ayr), 23.48 secs., 44.6 m.p.h.; 2, ‘* Faro’’ (Mr. Williams, Bournville), 25.82 secs., 40.5 m.p.h.; 3, ** Tiny VI ”’ (Mr. Clark, Victoria), 26.22 secs., 40.1 m.p.h. Speeds approximate, after correction for length of line. eed M. SUZOR’S “ NICKIE V” The next event of the day was the Miniature Speed Championship, this being for the lightweight flash steam and 15 c.c. I.C. engines. The highlight of this event was undoubtedly the whirlwind performance of Mr. Martin’s ‘* Tornado.’’ He returned an average speed for the 300 yards of 34.40 m.p.h., but in a lap after completing the course, he returned a time of 4.7 secs., which works out at around 43.5 m.p.h. Well done, Mr. Martin, who has shown that the *‘ Queen Mary ”’ isn’t the fastest boat to leave Southampton, although perhaps the most comfortable. The final placings were: 1, ** Tornado II’’ (Mr. Martin, Southampton), 17.84 secs., 34.40 m.p.h.; 2, ‘‘ Derive IV ’’ (Mr. Heath, Victoria), 24.68 secs., 24.90 m.p.h.; 3, {Mr. Duffield, King’s Lynn), and ‘*‘Mrs. Frequently’’ {Mr. Wraith, Altrincham), 24.78 secs., 24.80 m.p.h. The last event was the 300 yards Championship race for the big fellows (up to 16 lb. flash steam and 30 c.c. I.C.). Was there ever a more hotly contested race? At the end of the first round there were four boats between 14.50 and 15.75 secs., with only 0.05 secs. advantage of Mr. Rankine over Mr. Cockman’s “* Ifit.’”” M. Suzor got going, too, only to find his new piston a little too tight, otherwise he would have made the fifth boat in between those times. Ee GLARE. S “TINY 7 ” However, the success of Mr. Martin suggested to “*Tfit ’’ that she ought to be first and that her real form should be produced, with the result that she brought her time down from 14.55 to 13.80 secs. Mr. Rankine, however, was not to be done, but he only improved from 14.50 to 13.90, with the result that Mr. Cockman won his first championship race. Final results were: — 1, ‘* Ifit’’ (Mr. Cockman, Victoria), 13.80 secs., 45.40 m.p.h.; 2, ** Oigh Alba ’’ (Mr. Rankine, Ayr (Glasgow S.M.E.)), 13.90 secs., 45.1 m.p.h.; 3, “* Faro ’’’ (Mr. Williams, Bournville), 15.50 secs., 40.5 m.p.h. After correction for line length. Some points worth noting from the racing! Will there now be a rush to learn something of flash steam after the success of Messrs. Martin and Cockman? How does the two-stroke stand after Messrs. Rankine, Heath and Duffield’s success with them, and M. Suzor might have been in the picture. Was Mr. Bratley’s four-stroke the most powerful one there? A _ pity Kingston-upon-Hull couldn’t produce a better boat, otherwise Mr. Bratley, in the first instance, looked a possible winner. Last year, or at least on a previous occasion, Mr. Bratley had an Aspen valve gear—a pity he had to give it up, but he seems to have got quite a lot of horses with the present arrangement of things. From the results of the timing, it looks as if results are getting too hot for hand timing, and that all races will have to be electrically recorded; a pity the tape wasn’t working on Mr. Martin’s memorable run. Incidentally, when Mr. Cockman had his high-speed run in the championship race, he did five laps in 23.64 secs., which, with the correction for line length, was about the same speed as he returned at Wicksteed last year, when he created an English record for flash steam. * KEN. G. WILLIAMS’ “‘ FARO” re

MARINE MODELS 83 BUILDING A PLANKED HULL By YARDSTICK (Concluded from page 53.) AVING fixed the two sheer strakes, offer the spiling plank to the boat again, and get the shape of the next plank. Planks must always be put on in pairs. It should be noted that the nails are long enough to go slightly into the moulds, but that does not matter. Planks must be carefully fitted edge to edge, and glued. As no caulking is employed, the fit is a matter of importance. When the first group of planks has been completed, divide the remaining space into two, and mark out for the other planks. It will be noticed that as planking proceeds the sny and taper alter. It should not be necessary to force the edges of the planking together at any point, and if this is done the boat will have a tendency to open up at this point. On the other hand, if the ends of the strakes are forced up, the boat will have a tendency to hog (the ends drop), and go out of shape. Before putting on the garboard strakes, mark the position of the intermediate rib slots, so that these points may not be nailed. Some builders like to screw all along the garboard instead of nailing to the backbone. The boat must be glasspapered down well until the hull is perfectly fair. Start with medium glasspaper and finish with fine. Remember that paint or varnish cannot conceal rough workmanship, and rub the boat down thoroughly. While doing so, look at her from all possible angles. As before, wrap the glasspaper round a piece of thin, flexible wood, and work across the planking diagonally. The rubbing down must be done before removing from the building-board, to avoid straining the hull. The boat has now to be removed from the building-board. Take out the screws that hold the cross-pieces to the building-board, and those through the tab on the nose and packing pieces at the stern. Lift off the building-board, moulds and all. Unscrew the packing pieces from the moulds. The next step is to remove alternate moulds. This will give room to work while we are putting in the alternate ribs. The easiest way to get the moulds out is to turn them fore-and-aft. If any difficulty is experienced, a bit can be sawn out of the centre and the mould got out piecemeal. The nails have to be turned over (or clenched) on the inside, and this can be done where the moulds are out. The hull has still the support of the alternate moulds, and this leaves less to be done when the moulds are all out, and also avoids the chance of scratching the hands in working. The points can be turned straight down and hammered flush. A flat iron held against the head will not only support the side, but prevent the possibility of driving the nail back. For turning the points as well as planking, a light hammer should be used. The intermediate ribs are boiled until pliable, and then bent into the boat, the lower ends being glued and inserted in the slots cut for their reception. They should be glued to the planking and inwales, and got down to the planking properly. Just a few nails here and there can be used at first, and the remainder of the nailing completed when the glue has dried. These nails can also be turned over. A brad punch will be useful here, and its use will avoid bruising the outer skin which has been rubbed down. If any further rubbing down is needed, it should be done before the remaining moulds are removed. : Starting at the ends, remove the remaining moulds, turning down the nails as each is removed. When about a third of the way along the boat from the ends, put in ties from inwale to inwale to act as temporary deckbeams and prevent the boat’s sides springing out of place. The last mould to come out will be a centre one. The gaps between the inwales and planking in between the ribs have now to be filled in with pine packing pieces. It would, of course, have been possible to use a thicker inwale and notch for the ribs, but had that been done, it would not have bent in a smooth, even curve, but gone to a series of flats. These pieces are glued in position and come flush with the top of the inwale. The top of the stemhead and fashionpiece have now to be carved to form the chamber for the deck, and a piece of the decking can be used as a gauge. The fashionpiece has, of course, to be cambered to the plans also. The curvature and depth of the chamber should

84 MARINE have been marked on the forward side before the backbone was assembled, but if this has not been done, a cardboard template can be cut. The rudder tube is next made and fixed in position in the usual way. The next step is to make and fit deckbeams. These are cut straight on the underside and should have a depth of 3/16in. at the sides and 3/16in. plus amount of camber at the middle. They can be made of iin. pine, and should be spaced not more than 6in. apart. Beams should be arranged to fall under the most important fittings, such as the horses, steering pulleys, ends of hatchway, mast slide, etc. The ends of the deckbeams are let in flush with the top of the inwales, and glued and screwed in position. When the deckbeams are in, the temporary ties can be removed. The lead casting should be cleaned up, using old files and emery paper. Any blowholes should be filled with solder or hard stopping made of red lead and gold-size. The top of the casting must be shot dead straight. This is done with an iron jack plane, set fine and lubricated liberally with turpentine. If this is done the lead will plane as easily as wood, and if the keel is too heavy the surplus can be taken off very quickly. Put a weight to correspond with the rig in the position the mast will come, and test the fore-and-aft balance. This should coincide with the Centre of Buoyancy marked on the plans. If any adjustment in this respect is needed, and the keel has cast overweight, holes can be drilled from the upper face downward into the lead until the balance has been adjusted. These holes are afterwards filled up with wax to prevent their becoming a lodgment for water. In testing the total weight for the boat, allow for deck, paint, etc. Locating pins have to be fitted to the ends of the keel. This is rather a tricky business, as the fit must be exact. If the builder has any doubts as to his ability in this respect, he can drill holes from the outside, through the lead, and use fine screws instead. To drill lead, lubricate the drill freely with turpentine, and lift the drill frequently, and clear it. Put an iron screw in first to cut its way in the lead, then remove this and substitute a brass screw of the same size. The hole will have to be filled in with solder or stopping. The way to finish off the bottom of the keel bolts will be seen from the drawing from the backbone, and recesses must be made in MODELS the lead accordingly. When the keel has been adjusted, it can be fixed finally. First give the wood at the joint a coat of priming, of half varnish and half turps, and let this dry. Next, coat the wood and the upper surface of the lead fairly thickly with white lead paint, and bring the surfaces together and screw the nipples on the keel bolts down firmly. Pull up a little on each bolt in turn. The inside of the boat has to be varnished, but before doing so, look all the seams between the planking over, and, if there are any gaps that want caulking, they should be attended to by either gluing shavings of wood and putting them between the planks, or filling with plastic wood. Give the inside of the boat two coats of priming, consisting of half varnish and half turpentine, followed by three coats of varnish, letting the varnish dry properly between each. The varnish should be worked well into all joints and will serve to stiffen the boat no end. After the varnish has dried, the mast step can be fitted, also the carrying handle. This should be of stout leather with washers above and below the leather. The deck can be }in. yellow pine or 1 / 16in. waterproof aeroplane three-ply. It should now be cut to size and lined out in the usual way. Pieces of sailcloth should be glued where the mast hole, hatch and hole for the rudder tube are to be made before these are attended to, to ensure the wood is not split, and the thwartships cuts made first. Reinforcement pieces should be glued to the underside of the deck in the position of all deck fittings that do not fall on deckbeams. These can be }in. mahogany. The hatch cover, consisting of a slab of 4in. cork sheet glued on the underside of a wood hatch cover, can also be fitted. The underside of the deck can be varnished one coat of priming and two of varnish. All varnish used should be best quality spar or boat varnish, such as Rylard. Many plank builders like to varnish their work all over, but this is very ugly, and not like a real yacht. If it is desired to varnish all over, a painted boot-top will improve the looks of the yacht immensely, since it will break the mass and make the yacht look much more slender and graceful. Better still, is to paint up to the waterline and varnish above. (Concluded on page 88.)

MARINE PETROL ENGINE MODELS & HYDROPLANE 85 TOPICS By KENNETH G. WILLIAMS HIS year’s regatta season opened with a very enjoyable visit to Swindon, which gave first place in the main event to Mr. Noble, of the Bristol Club; a win which proved very popular on account of his dogged persistence in the face of ill-luck for a long time. The usual crop of troubles was in evidence for many boats, which have not improved by lying on the shelf or in a damp workshop during the winter months. The new craft and those embodying alterations or fresh components do not settle down at once, and need some little time for the correct adjustment to be found. Mr. Pinder produced a very interesting new hull, in which “Rednip’s” original engine had been installed. This boat is developed on the three-point suspension plan, and is built with a very narrow box body, having side planing surfaces or pontoons attached after the style of “stub wings,” embodied in certain types of flying boat, such as the “ Dornier D.O.X.,” or the American “China Clipper,” but, of course, having the planing surfaces projecting below the main hull. The unusual feature is that the hull is divided into two entirely separate compartments, the foremost housing the power unit, while the stern section contains the ignition equipment, and there is actually a gap in the under surface between the two, This boat had some trouble in getting away, and twice overturned; the impression I had was that propeller thrust at starting lifted the fore planing surfaces clear of the water, and the narrow beam at the stern was insufficient to resist torque reaction, so over she went. | wonder whether reversing the plan view arrangement would work better, with a centre fore plane about 9in. wide and two rear planing surfaces of about 2in. wide. However, Mr. Pinder tells me that when making a gentle start by use of his delayed throttle control, he has managed to get away without mishap, and that the hull is very stable at speed. Victoria Park and Bournville Clubs’ regattas followed in quick succession, and both provided good sport, with Mr. Cockman’s “ Ifit ” as the high light on both occasions. At the International event at Victoria Park, we had the pleasure of welcoming M. Suzor, who brought over “ Nickie V” from Paris, and many of us were delighted to renew his acquaintance. ‘ Nickie’s” hull, of conventional boat-shape in plan, is built of mahogany, and has a perfectly flat bottom; the planes are formed by aluminium sheets secured at their forward ends and supported by small metal pillars, which provide a means of adjustment to the angle of incidence. A small well in the bottom just above the fore plane gives clearance for the bottom of the crankcase, to allow the engine being mounted low in the hull and keep the centre of gravity down. M. Suzor’s craft gave a very creditable performance, although somewhat short of its previous best, after displaying a little temperament at the start. The two-stroke engine installed is a really fine piece of work, and does deliver the goods, although the adjustments appear to need careful handling to ensure getting the boat off the mark. In previous years the French champion had a style entirely his own when running the engine up; he stood in the water facing the nose of the boat, which was gripped between his knees, the right hand grasping the stern to give control over the depth of immersion of the propeller, while with the left hand he made the various adjustments to the multiple carburetters. This year he adopted a method which is in more general use among competitors; the hull is gripped by the right hand and braced against the right leg, while the left hand is free for controlling the engine; as scon as everything is correctly set, the boat may be released at once, without having to move around in the water, The note M. Suzor’s engine emits is really a joy to the speedboat enthusiast, and the envy of many, with the probable exception of Mr. Rankine, that canny Scot, who journeyed from north of the Tweed to take back the 500 Yard International Race Trophy and the Silver Medal for the 300 Yard Speed Championship. Your humble scribe gathered a few crumbs in the silver medal for the 5-lap race and the bronze for the 3-lap, at 39.6 m.p.h. The outstanding performances of the day were both put up by flash steam boats, Mr,

86 MARINE MODELS M. SUZOR’S ** NICKIE V ”’ MR. RANKINE’S NEW HULL MODEL POWERBOAT REGATTAS V.M.S.C.—Club Regatta, April 9. Guildford.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, July 9. Swindon.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, May 7. N. Staffs —M.P.B.A. Regatta, July 9. V.M.S.C.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, May 21. W. Midlands.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, July 16. Bournville.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, May 29. Malden.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, July 23. Blackburn.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, June 4. Wicksteed.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, July 30. International.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, June 11. Fleetwood.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, August 6. S. London.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, June 18. Farnborough.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, August 20. W. London.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, July 2. Grand.—M.P.B.A. Regatta, September 17. V.M.S.C.—Club Regatta, date to be fixed.

MARINE Cockman’s “ Ifit ” touching 50 m.p.h., and returning over 44 m.p.h., to win the speed championship; while Mr. Martin’s little * Tornado ” astonished everyone by getting in one lap at about 42 m.p.h., which must be the best ever for a boat of its size. Mr. Rankine has managed to regain his former speed and still stay on top of the water. His hull, which is about 1lin. wide at the bows, tapers evenly to about 5in. at the stern, over a length of slightly more than 40in. The shallow step is situated at about one-third the length from the nose, and there are two metal running plates of slightly greater inclination than the surface of the fore plane itself. Forward of these, are two 8in. long metal planes, 24in. wide, held away jin. from the main plane, in the form of inverted troughs, open at both ends. These auxiliary surfaces do not normally contact with the water, but give extra lift if the nose drops or tends to dig into a wave. They are made of springy duralumin sheet to provide some cushioning effect which gives a gentle extra lift when required, and not a hard thrust. The active surface of the rear plane is also a springy metal plate, and the owner claims that it softens the running in the same way. This hull almost seems to fly, and runs more off the surface of the water than on it. There is a peculiar side to side “ patter” on the two fore plane running surfaces, but there is no sign of this becoming cumulative with a tendency to overturn the boat, and in my opinion the springy plates help a lot in this respect. Several other craft which appeared, created a very good impression. Mr. Parris’s “Wasp” was very steady and reliable, while exceeding 39 m.p.h. I was glad to learn that his hand has recovered from the bad gash received when operating the ignition switch lever of his boat at Victoria Park Club regatta a few weeks earlier. It is always safest to use a stick to perform this office when handling a fast boat, and I notice he has now adopted this practice, which can be earnestly recommended to all concerned. Mr. Clarke’s “ Tiny,” of Victoria Park, is going very well now; the running of this hull reminds me very much of “ Betty’s ” performance in the flat way it sits on the water. The four-stroke engine is an outstandingly good piece of work: it has an S.U. type of carburetter, fitted with a metal gauze screen over the air intake, which should serve to safeguard the engine from damage, by preventing water MODELS 87 being taken into the cylinder in the event of a capsize. Mention of “* Betty,” which was an absentee at the International, reminds me that Mr. J. B. Innocent is convalescing from an illness during recent weeks, and is now progressing favourably, while his brother’s wife is also recovering well from an operation for appendicitis. Another interesting engine, which promises well in the future, is Mr. L. Bratley’s, from Hull. Last year it appeared with an “Aspin” type of rotary valve, which certainly worked, but owing to difficulties in obtaining reliability at high performance in this small size, the owner has now substituted an O.H.C. poppet valve head, and the horses certainly appear to be there. His hull proved disappointing, and | fancy part of the trouble is due to the weight being carried too near the stern. There were several very spectacular capsizes at this regatta, and many visitors had cause to wish they had umbrellas in readiness to save a wetting when a boat threw large lumps of pond over them. This trouble is most frequent on lakes with vertical concrete sides, which cause wave rebound, and maintain a choppy surface on the water for quite a long time after a boat has run, or from the disturbance set up by competitors and others wading about when getting a boat away. A rather curious effect of this nature was noticeable on the pool at Moss Lane, formerly used by the Altrincham Club. One point of the lap circle ran within 4ft. of a brick boundary wall, and when a boat passed on the first lap on undisturbed water, all was well, but the wash created travelled the short distance and back again just in time to catch her a smack on the side on the second lap. Any boat doing a good speed got into a vicious wriggle, and if she was normally a bit lively, a capsize was very probable. Strangely, on any subsequent lap, the disturbance of the surface seemed to cancel out and there was no further trouble. Unfortunately, planing surfaces on a hull ideal for smooth water, make the craft very wild on choppy water, and conversely, a suitable design to keep stable in the latter conditions often suffers from excessive drag on very smooth water, with consequent loss of speed. Most hydroplane hulls show in their design the influence of the builder’s home waters, and this feature is often noticeable at regattas, where competitors come from all over the country.

88 MARINE MODELS BRADFORD M.Y.C. A beginner recently asked me to pass an opinion on his hull, which was very dirty running. The engine, a new one, was of good design, and in good shape, developing plenty of power, but the hull simply would not lift —was slow, and threw out a tremendous spray on both sides. A straight edge placed across the tips of the two planes showed that the fore plane had no lift on the running portion, and had even a negative angle on the last #in. This is fatal to clean running, because the fore part of the hull is being pushed around as a displacement boat, and since the displaced water must go somewhere, it takes the line of least resistance, which is sideways, and shows itself as a heavy spray on both sides. The speed is brought right down, of course, with the engine pulling its heart out to no purpose. The remedy was to add a metal facing of thin, hard-rolled aluminium under the foreplane, either recessed at the nose end or filed to a thin edge, well secured with countersunk screws and supported by a wedge-shaped packing, to produce the proper lifting angle. On the next trial the difference was astonishing, the hull lifted cleanly at once, showing light under the step, the dirty running disappeared, and the speed jumped up several miles per hour right away. BUILDING A PLANKED HULL (Concluded from page 84.) To strike a horizontal waterline on a planked boat by eye is almost impossible. Chock the boat up firmly on an even keel on a level surface. A big sheet of plate-glass is admirable, but everyone has not got one handy, and use a scribing block, scribing the waterline right round the boat. The best priming for a planked boat is one containing varnish, but otherwise the painting is just the same as for a bread-and-butter boat. In a magazine article it is impossible to repeat the entire processes of fitting out and equipping a model yacht, but if the novice uses the above in conjunction with such a book as ‘‘ How to Build a Model Yacht,” by W. J. Daniels and H. B. Tucker, price 2s. 6d., postage 3d., from MARINE MOopELs Offices, he should be able to understand the way to build a planked yacht. The book referred to deals solely with bread-and-butter building, so this article may be considered (with apologies to the authors) as being more or less supplementary to it. The Garbutt 6-m. Trophy was raced for on May 20, under light and fluky wind conditions. Results as follows: ‘* Plover’? (F. C. Hirst, sailed W. Roberts), 21; ** Pennine ’’ (S. Brayshaw, sailed S. Roo), 16; ‘* Challenge ’’ (E. North), 11; ‘* Red Admiral ’’ (Mrs. Snow, sailed Geo. Snow), 10; ‘*Greta’’ (J. P. Clapham), 9; ‘* Kathleen” (A. Arnold), 8. Mrs. Garbutt was present, and handed over the Trophy. The Victor 36in. Cup race was run on May 21, with the following results: ‘* Edith Roberts ’’ (sailed W. Roberts), 22; *‘ Duco’’ (H. Chadwick), 15; ** Melinki *’ (K. Chadwick), ** Frisker ’’ (H. Atkinson), and ‘* Mercury ’’ (E. Edmondson, sailed H. Mower), 11; ** Red Rose ’’ (H. Short), 5. A race for a prize given by Mr. S. S. Crossley was run on June 11, and was competed for by eight 6-m. yachts. The prize, a handsome barometer, was won by A. Arnold with ** Kathleen,’’ with 28 points; ‘* Red Admiral *’ (Mrs. Snow) and *‘ Plover ’’ (F. C. Hirst) tied for second place with 25 points each. Mr. Crossley was present and handed over the prize. J. P. CLAPHAM. LONDON MODEL YACHT LEAGUE The third round of the series of races for the Stanton Cup was held at Highgate on June 4. Owing to an unfortunate error, the South-Western Club’s representatives were not present, and they will have great difficulty in making up the ground thus lost. The wind was very variable and many of the skippers had great difficulty in coping with the conditions. To those who did well, therefore, all the more credit is due. Mr. Headlam, of the Forest Gate M.Y.C., and Mr. Fitzjohn, from Clapham, tied, with 16 of a possible 24 points, for first place. The scores were as follows : — Highgate M.Y.C.— Mr. Edmonds 14, Mr. Yorston 10=24. Total 96. Clapham M.Y.C.— Mr. Fitzjohn 16, Mr. Hatfield 12=28. Total 90. M.Y.S.A.— Mr. Normanton 10, Mr. Becq 6=16. Total 86. Forest Gate M.Y.C. Mr. Headlam 16, Mr. Howard 12=28. Total 84. South-Western M.Y.C. Total 60. Mr. C. J. Carter, of the Highgate M.Y.C., was O.0.D., assisted by a team of umpires, starter and scorer. The visitors were afterwards entertained to tea by the Highgate Club, and a very enjoyable day was thus brought to a close. J. H. Y.

MARINE MODELS 89 WOODEN MERCHANT-SHIP BUILDING By G. W. Munro (Continued from page 68.) HEER-PLANK, Sheer-strake, or Paint- S strake, broad strakes of plank put round the vessel at the tops of the timbers. They are commonly thicker than the other planks of the top-sides. On the lower edge of the paint-strake, a moulding is formed, corresponding with that on the edge of the gunwale or plank-sheer.| Sheers, two spars or masts lashed together at one end, and set up like the two legs of a triangle; to their upper point a block and tackle are attached. They are used for hoisting up the stem, sternpost, the frames, etc. Shiftings of the planks, a term used for expressing the arrangement of the planks so that they may overlap one another with their ends, forming a shifting of their butts, and bind the ship. When English plank is used, the shiftings or overlaunchings of the plank is five feet, or five feet and a half; but when the foreign timber is used, they are generally made seven feet, and there are always three strakes of plank between butting on the same timber. Shores, pieces of timber employed as props or temporary supports in shipbuilding. Siding-dimension, 1s the breadth of the timbers; moulding-dimension is their thickness. Sir-marks, a mark made on the moulds of the timbers, to distinguish the spot where the bevel is to be applied in bevelling the timbers. Sliding keels, large pieces of wood, made to lower down through the main keel of the vessel. Sliding planks, pieces of wood which are laid on the bilge-ways, and slide the vessel into the water when launching. Slip, the inclined or sloping surface of the ground on which the ship is built. Slip, Mr. Morton’s Patent, a frame or cradle, which is drawn up or let down at pleasure into the water, having a great number of small wheels running upon a railway or inclined plane. It is used for hauling ships out of the water to be repaired. When the vessel is to be hauled up, the cradle is let down, and from its having a good deal of iron about it, it has no tendency to float off the railway; the vessel is then brought above the bears upon ing with it of only a cradle, and as soon as ever she it, the cradle is drawn up, bringthe ship, which, by the strength few men, is thus completely hauled up. The principal object of this invention is to provide a cheap substitute for dry docks, where it has not been thought expedient or practicable to construct them; and, both in point of economy and dispatch, it has been found completely to answer the purpose for which it was originally intended. The patent slip, after the extensive experience that has now been had of it, is admitted to possess the following advantages : — 1. A durable and substantial slip may be constructed, under favourable circumstances, at about one-tenth of the expense of a dry dock, and be laid down in situations where it is almost impossible, from the nature of the ground, or the want of a rise and fall of tide, to have a dock built. 2. The whole apparatus can be removed from one place to another, and be carried on ship-board, 3. Where a sufficient length of slip can be obtained, a number of vessels may be upon it at once; and, in point of fact, two or more are often upon the slips ready constructed, and under repair at the same time. 4. Among the other advantages peculiar to the slip, it may be observed that, every part of the vessel being above ground, the air has a free circulation to her bottom and all around her; in executing the repairs, the men work with much more comfort, and, of course, more expeditiously; and, in winter especially, they have better and longer light than within the walls of a dry dock; while considerable time is saved in the carriage of the necessary materials. The vessel, in short, is in a similar situation to one upon a building slip. 5. No previous preparation of bilge-ways is necessary, as the vessel is blocked up on her keel, the same as if in a dock; and she is exposed to no strain whatever, the mechanical power being solely attached to the carriage which supports her, and upon which she is hauled up.

90 MARINE 6. A ship may be hauled up, have her bottom inspected, and even get a trifling repair, and be launched the same tide; and the process of repairing one vessel is never interrupted by the hauling up of another— an interruption which takes place in docks, from the necessity of letting in the water when another vessel is to be admitted. 7. A vessel is hauled up at the rate of 24ft. to 5ft. per minute, by six men to every 100 tons; so that the expense both of taking up and launching one of from 300 to 500 tons, does not exceed forty shillings. Snying, a plank is said to have snying when it is much curved or bent edgeways. Spiles, small wooden pins driven into nailholes, to prevent a vessel leaking. Spilings, the dimension of the twisting or curving of a plank, measured from the edge of a batten or rule-staff. When the snying of a plank is to be measured from the bottom of the vessel, a straight-edged batten, of four or five inches in breadth and 4-inch in thickness, is applied, quite flat against the timbers; it is placed in the direction of the intended plank, as near as possible without bending it edgeways (this is termed pending the batten or staff). You then measure from the edge of the batten to the seam of the plank put on last, against which the other is to fit, and mark the distances on the batten, taking a measure perhaps at every 14ft. or 2ft. apart. The rule or batten is then taken down from the timbers, and laid on the plank which is intended to be lined off. The same distances which are marked on the batten are then measured from the edge, and marked on the plank; and after they are all measured off, the plank is lined to the proper curve edgeways. This is called the snying of the plank. Spirkitting, is a strake or two of plank wrought round the inside of the top-timber, between the waterways and the under side of the port-sills. In merchant ships, there is only a short strake at the bow, and it is sometimes called quick-work. Square, a piece of timber is said to be square when its sides form right angles to each other. Square frames, those that have the planes of the sides of the timbers at right angles to the keel. Square tuck, a name given to a part of the MODELS after-run, when it ends in a straight plane which is nearly vertical, in place Aj the plank running up to the counter. Stability, the property which enables a ship to stand upright in the water, and also to regain that position when the force which has caused her to deviate from it is removed, Stantion or Stanchion, a support. Standards, large iron knees fitted between the beams of the upper and ’twixt-decks, bolted to these beams and the ship's side. They are sometimes called iron staple-knees. Staples, crooked pieces of metal used for various purposes. Starboard-side, the right-hand side of a ship when standing aft with your face to her bow. Steeling-strake or plank, one which does not run all the way to the stem or sternpost. Steering-wheel, a wheel to which the tillerrope is attached, used for steering the ship. Stem, the principal timber which forms the bow of the vessel, into which the ends of the bow-plank are fixed. Stemson, a large knee fixed on the inner side of the apron, and upper side of the upper keelson. Steps of the Masts, a large piece of timber bolted down to the keelson, having a mortise in it, which receives the tenon on the lower end of the mast. Sometimes the step for the mizzen-mast does not lie upon the keelson, but rests upon a large piece of timber fixed between two of the hold beams. Stern, the after part of a ship above the counter, and in which windows are made to give light and air to the cabin. Sternpost, a strong piece of timber, generally extending from the keel to the upper-deck. It fits to the after-end of the keel with mortise and tenon, and is fastened by the deadwoods and heel-knee. Sternpost, inner, the inner sternpost is fitted on the fore side of the main sternpost, and generally extends from the keel to the under-side of the wing transom. Stools, pieces of plank which are bolted edgeways to the quarters of small vessels, to form the mock quarter-galleries. Stringers, strakes of planks wrought round the inside at the height of the under-side of the beams. They are bolted to the clamps and timbers, and are hook-scarphed. As they are put on edgeways, and serve as

MARINE a shelf to rest the beams upon, they are sometimes called shelf-pieces. Tabling, making projections and recesses alternately on two pieces of timber which are to be fastened together; the tablings prevent the pieces from drawing or slipping upon each other. Taffrail, the continuation of the main-rail across the stern. Tenon, a square projection on the end of a piece of timber, or surface, corresponding in size and position to a hole or mortise in another piece, to which it is to be joined. Thick-stuff, a name for a plank which exceeds four inches in thickness. Throat, the middle or centre part of the hollow of a timber, knee, or breast-hook. Tiller, a lever fitted into the head of the rudder for steering a ship. Timbers, the ribs of a ship; the pieces of wood of which the frames are composed. Timber and Room, Room and Timber, or Birth and Space, mean the distance from the side of one timber to the same side of the next; or the distance from moulding edge to moulding edge; the birth and space of the timbers is always I4in. or 2in. greater than the breadth or siding dimension of the timbers, and can never be less. Tonguing, the forming a kind of tenon on the end of a piece of timber which is to butt against another. Tonnage, the cubical contents of a vessel, reduced to the number of tons which she will carry. Owing to the various constructions of vessels, and as they are all measured by the same rule, and not actually gauged, some carry more than their calculated tonnage, while others carry less. Top and Butt, in planking, means working the plank in the anchor-stock fashion, laying their broad and narrow ends alternately fore and aft. This is practised, in order to save materials, when planking with English oak. Top-sides, all the ship’s sides above the bends. Top-timbers, timbers forming the top-sides. Touch, the broadest part of a plank worked top and butt, which place is about 5ft. or 6ft. from the butt end. Trail-boards, pieces of fir fitted between the cheek-knees of the head; they are carved with a device corresponding to the figurehead, Transoms, large pieces of timber which lie horizontally across the sternpost, and form the buttock; they are bound together at MODELS 91 the end by a timber called the fashion- timber. Transoms-knees, knees bolted to a ship’s quarters and the transoms. Trimming a piece of timber, working it to the proper shape and bevelling. Tree-nails, cylindrical oak pins driven through the plank and timbers to fasten them together. Truss, a carved bracket employed to support the carved work over the stern windows. Tuck, the place where the butts of the bottom plank in the after-run terminate; generally a little above the wing transom; and at this place a large moulding is wrought across the counter, which is called the tuckrail or tuck-moulding. Tumble-home, the inclination inwards of the top-timbers towards the middle of a vessel. Under-bevel, a bevel that is within a square. Upper-deck, the uppermost deck that extends from stem to stern. Upper-works, a name for that part of the hull of a vessel above water. Waist, a name given to that part of the upperworks above the main-deck and between the main- and fore-channels, Wales, the principal strakes of thick plank, wrought round the outside of a vessel, about the load-water mark. They are sometimes called the bends. Wash-board, a strake of plank in the bulwarks, put on with small bolts and forelocks; it can be taken off at pleasure, in order to get the stantions properly caulked. Windlass, a strong piece of wood turning round on an iron spindle, which is fixed into its ends, and is turned round by levers, called hand-spikes. Whelps, pieces of wood or iron bolted on the windlass, to save the main piece from being chafed by the cable. Whole-moulding, an old method of moulding vessels, now almost out of use, except for boats. Winch, a small windlass. Wing-transom, the uppermost of the main transoms. Wood-lock, a piece of wood fitted into the fore part of the rudder, to prevent it from being unshipped. Wrain or Wrung-bolts, planking. ring-bolts used for Wrung-staff, a piece of wood used also in planking. (To be continued.)

92 MARINE HAVE received quite a number of en- | quiries as to progress on my destroyer model. Unfortunately, owing to pressure of work, I have been unable to do much to her this winter, but I hope to get to work on her shortly, and when I do, I will give readers any news of interest. In the meantime I have been hoping to give readers particulars of new craft built during the past winter, but others besides myself are behindhand so | shall have to postpone the pleasure of dealing with notable new models until later issues of this Magazine. A subject that has been in my mind for some time is lubrication. Quite a large number of models are powered with commercial engines, and the majority have insufficient provision for proper lubrication. As a general rule the only provision on commercial engines for lubrication is for fitting a displacement lubricator, yet for efficient running every moving part of an engine requires efficient oiling. Sometimes an oilhole is provided on the main bearings, and after the owner has dealt with this liberally with an oilcan, partial lubrication ensues and lasts for a minute or so, but after this the bearing is as dry as before. The ideal practice in lubrication is to have a film of oil in the bearings, so that these are not running metal to metal, but separated by a thin layer of oil. As long as the oil film is present the wear on bearing surfaces is negligible and friction reduced to a minimum. Of course, the viscosity of the oil must be suitable to the machinery it lubricates. Light, fast-running machinery requires a light oil that will easily permeate the bearings, while heavily loaded machinery needs a heavier, denser lubricant. Another factor to be considered in the selection of lubricants is the MODELS question of temperature. Under high temperatures oils tend to become more fluid, and very light oils tend to burn away. Too heavy an oil tends to produce drag, so it becomes a question of selecting the right oil to use, taking all the circumstances into consideration. Lubrication systems can vary from quite simple to most elaborate lay-outs, and should be planned in consideration of the plant used and the work it is called on to perform. Thus the plant of a prototype model requires a much less elaborate oiling system than is needed for a flash steam racing boat where everything is run all out at its extreme power output. By way of a start let us consider the simplest possible plant and its lubrication. Points that require lubrication are the cylinder walls in contact with the piston, the valves, valve gear, top and bottom ends, and shaft bearings. As will be seen, this comprises all points where friction can occur. To deal with these sertatim, we can start with the piston and cylinder walls. In comparatively slow moving engines displacement lubricators are perfectly satisfactory. The principle of these is too well known to require repetition here, but it may be mentioned that they function by the introduction of oil into the steam-chest. This is carried into the cylinder by the steam and distributed round the piston walls. If too little oil is introduced, insufficient lubrication ensues, but when too much oil is present, superfluous oil will be carried out with the exhaust steam, and a dirty, oily exhaust will result which (unless special precautions are taken) will spoil the finish of the model. Displacement lubricators function best where engines are run under a constant steady load, and when engines are alternately throttled down and opened up to full power,

MARINE oil supplies will be alternately starved and flooded. Given intelligent regulation and use, however, displacement lubricators are a simple and efficient method of lubrication for the ‘innards ” of a prototype model’s plant. Over-lubrication can, of course, be guarded against by the provision of an efficient oiltrap in the exhaust steam line. If this is arranged in the path of the hot gases from the furnace, the oil will be burnt instead of being distributed over the deck of the model. The size of the oiltrap will have to be governed by the size of the model and space available, but a good-sized oil-trap will guard against the possibility of ejection of unconsumed oil. For faster running engines, my personal preference is for forced lubrication, as with forced lubrication the amount of oil injected is under strict control, and nothing is left to chance. On many commercial engines the only other point that is lubricated is the main bearings and all that is provided is an oil hole. Although this is not remarkably satisfactory, matters can be improved by the provision of oil grooves to lead the oil across the full width of the bearing instead of simply oiling the part of the bearing immediately in line with the oil-hole. These oil-grooves are best arranged in the form of a V in the direction of the rotation of the shaft, and should not extend to the full width of the bearing or the oil will be flung out instead of lubricating the shaft. The oil-grooves must be sufficiently wide and deep to allow the oil to pass, but not so wide as to materially reduce the bearing surface, or so deep as to impair the strength of the bearing. The whole idea is to introduce sufficient oil to form a film between the metal surfaces. Bearing surfaces should be absolutely smooth and polished, and there should be a minute clearance between them sufficient to permit the presence of this film of oil, but nothing more. When a shaft is too tight in its bearing, there is insufficient room for the film of oil. The reader must not think that I am advocating sloppy bearings. A sloppy bearing is even worse than a slightly tight bearing, since the latter may eventually ease itself, while a sloppy bearing will rapidly become worse and worse. What I wish to convey is that a bearing must be just so, and then if properly lubricated, it will give good and prolonged service. Bearings should have commensurate width MODELS 93 and surface according to the work they are called on to perform. A bearing with insufficient surface is prone to wear quickly, besides being a source of weakness and lack of rigidity. On the other hand, over-large bearings set up undue friction, and absorb power. It should be remembered, however, that main shaft bearings have to carry the full power of the engine, and absolute rigidity at these points is essential. It should also be remembered that the power output of a steam engine is not a circular motion like an electric motor, and the main shaft, especially at the crankpin end, is engagedin converting a reciprocal motion into a circular one. Hence the strains are uneven, and good bearings are essential to ensure smooth running. For good wearing and easy running, main shaft bearings require proper oiling. A simple oil-hole may be all very well just so long as one stands over it with an oil-can and lubricates freely at frequent intervals, but for the long running that model marine engines have to do, it is desirable to have some semi-automatic or automatic method of supplying oil to the bearings. For a prototype engine drip lubrication from a wick-feed oil-box is a very suitable method of dealing with main shaft bearings, but for really high-speed engines forced feed lubrication is essential. As there are other points on the engine that require lubrication, this means that pipes have to be led from the oil-box or pumps, according to the system used, to the various points to be lubricated. I have already given particulars of oil-boxes in the pages of this Magazine, besides details of various pumps and methods of driving same, also in How to Build a Model Steamer, published by Marine Models Publications, Ltd., so I will not repeat them here, my present article being on the subject of lubrication generally. In addition to the main bearings, valve gear, crossheads and slides, top and bottom ends all require lubrication. To a certain extent the methods of lubrication employed for these points must depend on the design of the engine that is being dealt with. Let me take a specific instance. Some engines have an enclosed crankcase. If these are high-speed engines, the revolving cranks will turn at such a speed that although there is a good depth of oil in the crankcase, this will be whirled aside and the cranks revolving in air owing to the centrifugal force set

94 MARINE up. Thus, although there is plenty of oil, the bottom end might be dry. Matters can be considerably improved by fitting a hooked scoop on the underside of the big end, but in racing engines forced feed through the crankpin is necessary. If a hooked scoop is used, the best result is obtained when this is in conjunction with a trough shaped to the arc of the scoop’s path and closed at the end. As the scoop is continued beyond the point of the scoop’s orbit, oil is trapped so that the scoop operates into a mass of oil which cannot escape. For the valve driving gear the same applies, and, if an eccentric is used, this also can be fitted with a hooked scoop. In some designs valve gear is run in an oil-bath, or trough. Slides and other external points can be dealt with by oil pipes, fed from the oil-box or pump, as the case may be. Although the builder must be guided to a large extent by the design of his engine, he must remember that oiling is needed at all points where friction arises. I have already mentioned that the quality of oil used must be suitable to the plant, but MODELS it must also be emphasised that oil must be clean and free from all gritty substances. Oil tins are often left open and exposed to dust and dirt. Oil cans are dropped on the ground and pick up grit, which, in turn, is shot into the bearings. Tins should always be wiped round the pourer before oil is decanted into the oil-can. Oil and grit practically forms grinding paste. Sometimes bearings are lapped out, but this is bad practice, generally speaking, since the abrasive tends to become embedded in softer metals, and it is impossible to remove it entirely afterwards. When running in a new engine or one that has just been overhauled, it is quite likely that a little stifiness may be experienced. It is a great mistake to rev the engine up all at once. For a start the engine can be turned over in the lathe, using plenty of clean oil. When it is first put under steam, only a short run should be given and that at a very moderate speed, again lubricating freely. After its first little run, the engine should be allowed to cool off before giving a second and slightly longer run. The work can be increased gradually as the engine settles down, and packings taken up by degrees as requisite. If an engine is run in this way, it will give better service in every way. For lubricating the inside of the engine, the thickest oil is not necessarily the best. In fact, there are special oils made for steam. In the case of engines which are called on for maximum output, such as flash steam racing engines, it is probably advisable to use colloidal graphite mixed with the cylinder oil. In super engines temperatures are a limiting factor in lubrication, and only specially prepared oils will retain lubricating properties. I will conclude this article by stressing the fact that however good or well made an engine is, it will only perform satisfactorily and give good service if care has been given to the provision of suitable lubrication. It is, therefore, well worth while to take the trouble to provide a proper lubrication system. (To be continued.) G. CURDIE, with winner of Walker Cup, Kilmarnock, ‘‘ SAIL HO’ and the Cup

MODELS 95 ttn MARINE TT Our Scottish Page : HE Fable of the Leetle Fish, bearing no rela- ts tionship to the Bonnar cat. Once upon a time, long, long years ago, there swam in a pool many fish, of all sizes and many different kinds. And they all gathered together, each to that of his own kind, in companies. And harmony dwelt with them, each loyal and helpful to his own company, and many companies combining together for the good of all. And the individual companies occupied their separate quarters and were happy and gay. Now it came about that feeding was sometimes better at one end of the pool, and, anon, at the other, and so the fish wished to move as occasion required to get the best food and enjoyment from their lot. But the two ends of the pool were far, far apart, and a weary road to travel. Thus it fell out that all the members of this or that company were unable to bear the strain of the long passage, and so only a few were selected by the others to travel the road and enjoy the fruits in season, and perhaps voice afar the merits each of its own company, which rejoiced and was exceeding glad if their members returned fat and well, and laden with honours. Or, if it chanced that the travellers came back void of honours, still it was not grudged unto them. And lo! into one of the companies came a leetle fish and was adopted by the tribe. And this leetle fish was eager and anxious to venture forth into the far quarters of the pool. But, it was only a very leetle fish, and of its own strength unable to travel the long road. So the other fish of that host gave of their own fat and fitted the leetle fish for the journey, not once but many times. And the leetle fish took it all and had many, many happy days. But the leetle fish was of a selfish and forgetful nature, and soon it quarrelled with the rest of that company and hied it hence to another group. And it came to pass in the fulness of time that its old company were decided on sending another fish the furthest journey of all, through many streams and vast pools connecting with another pond in a distant land. But did the leetle fish help the pilgrim? Alas! no. It did all it could to hinder and to decry the old company that had been so good to it. Why? What of the years to come? vidual inclination. We have just Moral, according to indi- returned from witnessing the largest open regatta staged this season, an entry of 34 6m. class models, representing seven clubs, assembled at Whiteinch, Glasgow, on the invitation of the Scotstoun Miniature Club, June 17. While dwarfed by some of the stupendous entries of the past—we were once faced with 64 12-m. on a Saturday afternoon—this constitutes quite a formidable entry to handle, and credit is due to the comparatively young organisation that essayed the task. A strong, gusty wind prevailed, ringing the changes al] round half the points of the compass from SouthEast to South-West, without warning, and with slams of considerable force. As a result, skippers had a hard task to decide on what trim to set, and frequently had the mortification of seeing their model, setting off with running trim, met a few yards from the stage with a sudden gust from the diametrically opposite quarter. Under such conditions many alarming fouls were inevitable, and it was really surprising that serious damage did not occur, although two competitors were compelled to withdraw disabled. Also luck necessarily entered into the racing and made it ‘* anybody’s day.’’ Three full heats were completed, and a number of resails were also necessary to balance the card. On one of these resails the winning flag depended, ** Clutha,’’ holding 12 points of the possible 15, with a resail to windward, losing the resail, and eventually dropping out of the prize list altogether. Final returns gave ‘* Kelvin ’’ (W. Brown, Dennistoun) first prize with full points. For the second and third prizes, ‘* Margaret ’’ (L. McLean, Miniatures), and ‘* Fairway ’’ (H. Chambers, Victoria), each with 13 points, sailed a final, which went in favour of ‘* Margaret.’’ For the fourth prize four models returned 12 points, but one of them had packed up, and the other three, sailing a deciding board, were led home by ‘‘ Nardana’’ (D. Deans, Dennistoun). | Notwithstanding the unfavourable, not to say strenuous, conditions, the afternoon was thoroughly enjoyable. It is interesting to compare the above prize list with that applicable to the Golfhill Shield race, which was carried through at Alexandra Park, Glasgow, by the Dennistoun Club, on the preceding Saturday, June 10. Open for 6-m. class and clubs within a radius of 25 miles of Glasgow, the entry of nine models was disappointing in numbers, but compensated for by the quality of the entrants. A fresh, steady breeze gave favourable beating conditions, and the complete tournament was sailed out, the possible score totalling 40 points. The new model, ‘* Margaret '’ (L. McLean, Miniatures), from the board of Andy Weir, put up a grand performance, and returned a card of 38, conceding only a single run to leeward, with a leading margin of 8 points over the runner-up, ‘Isa ’’ (A. Arthur, Alexandra). Third place went to *‘ Nardana”’ (D. Deans, Dennistoun), with 26, followed by ‘‘Wendy”’ (P. J. McGregor, West of Scotland), 25. Kilmarnock carried through the competition for the Walker Cup, confined to Ayrshire Clubs, on June 3, the 12-m. class being concerned. Symptomatic of the dying appeal of this class, only a single competitor, ‘‘ Neupon’’ (H. Miller, Saltcoats), who, as the holder of the Cup, was also defender, was present from outside the local club, and the entry comprised six only. ‘‘ Sail Ho! ” (G. Curdie, Kilmarnock) put up the best showing with the loss of two boards and regained the Cup from ‘* Neupon,’’ which ran second. Wind conditions were very light, freshening somewhat to-

96 MARINE wards the close. The West of Scotland Club were at home to Greenock on June 3, when a return match with teams of six 6-m. models was staged. tournament was completed and an addition, witness to the enjoyable sport. A nice sailing breeze, The full team extra heat in nature of the with beating condi- tions, contributed to this happy result. The West took the honours with a very wide margin of points with ‘* Wendy ’’ (P. J. McGregor), 28; ** Violet "’ (A. W. K. Rodrick), 25, and ‘*Charmee’’ (C. F. Arthur), 24, as leaders. The Greenock returns placed ** Squirrel ’’ (J. F. Watt), 10; ** Jean ”’ (A. Main), 8, and ‘* Redhead "’ (J. Watt), 5, at the head of their card. The position was reversed when the West visited Saltcoats a fortnight later, again with a team of sixes, for an inter-club match with the local boys. The conditions were strenuous indeed. ** A howling gale, I would call it,’ was the remark of one competitor. To some extent this was in favour of the local team, more accustomed to heavy wind than the inland club. Anyway, the stout little craft all battled into it and gave still another fine demonstration of the ability of this class to take everything that comes, high water or low, without flinching. Leading cards were returned by ‘*‘ Helen,’’ 30; ‘* Glance,’’ 274, and ** Anna III,’’ 27, for Saltcoats, and *‘ Violet,’’ 20, ** Edna,’’ 9, and ‘* Wendy,’’ 5, for the West. Totals: Saltcoats, 144; West, 38. The sort of defeat that the West seldom experiences. But no grousing, We submitted a ‘* stop press ’’ A. W. Littlejohn. * Fin-and-skeg. + Full Keel. Etc. “ Brunhilde,” Sea-going Diesel Yacht, 40 in. long, Fullsize plans, 8/6 “Maid of Rutland,” Cross-Channel metre long, Full-size plans, 6/6. Steamer, Steamer, 48 in. long, Binding, Vols. I, I, Il, IV, V, VJ, VU, VII, IX, X or XI (including case), 6/- post free. Bound Volumes. Vols. IV and V, 37/6; Vols. VI, VII, Vill, TX, X and XI, 12/6, post free. We can occasionally supply copies of earlier Volumes. Prices on application. Full-size, 5/6. WORKING MODEL STEAMERS, “ Zingara,” Cargo plans, 6/6. Two sheets 10/6 post free. 1 Half-size “ Coronet,” Paddle Excursion Steamer, 60 in. long, Half-size plans, 8/6. “ Boadicea,” Sea-going Tug, 60 in. long, Half-size plans, 8/6. « Awatea,” N.Z. Shipping Co. Liner, working model, 68 in. long, Full-size Plans, 21 /-. Back Numbers. Vol. I, Nos. 1 and 5, 2/6; No. 6, 1/7; No. 8, Nos. 11 and 12, 1/7. Vol. II, No. 1/1; No. 7, 1/1; Nos. 8 and 9, and 2,1/1; Nos. 4 3/-; No. 9, 2/6; 1, 2/6; Nos. 2—5, 1/7; Nos. 10—12, 1/1. Vol. Ill, No. 1, 2/65″No: 3, 2/6; No. 4, 5/-; Nos. 5 and 6, 2/6; No. y sigif ‘No. 8, 2/6; No. 9. 3/-; No. 12, 7/6. Vol. IV, Nos. 1—4, 2/6; No. 5, 7/6; Nos. 6 and 7, 21a No. 8, 3)-: No. 9: 2/1: Nos. 10 and 11, 1/7; No. 12, 2/6. Vol. V, Nos. 1—4, 1/7; No.5, 3/-; No. 6, 7/6; Nos. 7—9, 1/7; No. 10, 7/6; No. 11, 1/7; No. 12, 1/1. Vol. VI, No. 1, 7d.; No; 2,.2/1 : ‘Nos. ar 7d. ; No. 6, 2/1; Nos. 7—12, 7d. Vol. VII, Nos. 1—5, 7d.; No. 6, 1/7; No. 7, 2/1; Nos. 8—12, 7d. Vol. VIII, No. 1, 7d.; No. 2, 1/7; Nos. 3—5, 7d.; No. 6, 1/7; Nos. 7—12, 7d. Vol. IX, Nos. 1—5, 7d.; No. 6, 1/7; Nos. 142, 7d. Vol. X, Nos. 1—5, 7d.; No. 6, 1/7; Nos. 7—12, 7d. Vol. XI, Nos. 1—5, 7d.; No. 6, 1/7; Nos. 7—12, 7d. All post free. Other numbers out of print. ALL DESIGNS POST FREE. No returns can be taken more than seven weeks from date of issue.

Ww. H. BAUER, MODEL YACHT FIT-OUT AND REPAIR SERVICE SPARS, SAILS, FITTINGS and ACCESSORIES For all Classes. To order only. DECORATIVE, WATER LINE, SHIP MODELS AND HALF MODELS BUILT AND RESTORED. Workshops BUS – SERVICES: 11, 512, KING’S ROAD, 22, CHELSEA, LONDON, S.W.10 NEAREST STATION: 31. EARL’S COURT WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP WON WITH SAILS THE MADE OF ‘ENDEAVOUR’ X.IL. SATLCLOTR YACHTS ARE FAST WATERPROOF =: UNSTRETCHABLE UNSHRINKABLE Definitely faster and points higher. Lasts out many ordinary sails. A Few “A” AND Class X.L. Results : International Championship, 1935, 1st; 1936, 2nd ; 1937, 1st Allen Forbes Trophy (International), 1936, 1937, all 1st 1935, WEATHER Wing and Wing Cup (International), 1937, 1st il Scandinavian U.S.A. U.S.A. These new Yachts are the latest thing for fast racing work. All of the hulls are hand made in best yellow pine. The two largest Yachts are fitted with Braine type automatic steering. Painted Pale Blue. Cabin Skylight extra. International, 1934, 1935, 1936, all 1st Eastern Championship, 1937, 2nd 1936, Mid-West Championship, 1st ; 1937, 17 21 27 36 1st And many less important events. Used all over British Isles, India, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, S. Africa, U.S.A., Norway, Sweden, Belgium, Denmark, France. in. in. in. in. Yacht Yacht Yacht Yacht with with with with Prices : automatic rudder… automatic rudder… Braine type steering Braine type steering Carriage extra. sks es Se ase so aes Se vce 12/18/6 39/6 75/- COPPER NAILS. Specially made for the Yacht and Boat Builder, 2” long. Price 3d. oz. pkt. SEND Sails made at ordinary rates. 6d. FOR BOND’S W. G. PERKS, CAERNARVONSHIRE 357, BOND’S GENERAL O’EUSTON EUSTON ROAD, *Phone: EUSton 5441-2 CATALOGUE. ROAD LONDON, LTD. N.W.1 Est. 1887 <> ——-SAILS—_ <= CHAS. DROWN & SON Model Yacht Sail Specialists A World-wide Turkey Red Sails Reputation a Speciality for Fittings and nearly a Quarter of a Century Accessories to Order : Sail Cloth : Sail Plans Send stamp for Price List 8, ULLSWATER RD., WEST NORWOOD, LONDON, S.E.27. When replying to Advertisers please mention MARINE MODELS.